Marie Brennan's Blog, page 18

October 17, 2023

Happy (belated) (UK) book day to me!

Vaki þu, Angantýr, vekr þik Hervör,

eingadóttir ykkr Sváfu;

selðu ór haugi hvassan mæki,

þann er Sigrlama slógu dvergar.

My god, I was so busy yesterday that I didn’t even manage to post here about The Waking of Angantyr coming out in the UK. In my defense, I was not busy by choice; instead I got called in to jury duty for the first time in my adult life — all my previous summons have resulted in the website telling me the day before that I don’t have to report in. Well, I suppose it’s fitting that publication day for my bloody Viking revenge epic began with me waking up early enough to induce homicidal feelings . . .

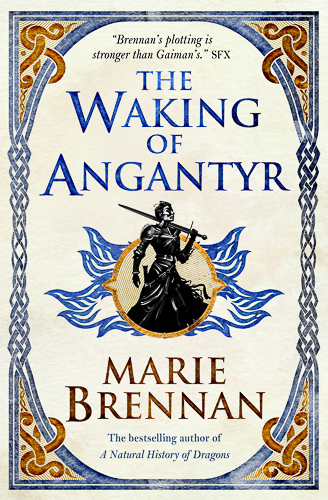

But even if I’m a day late in posting this, the good news is that book is still out! Yes, in this day and age where we place an unhealthy emphasis on how everything performs in the first twenty-four hours, I think it is just dandy for people to buy a book on day two! Or even day two hundred, for that matter. And Titan Books have given it such a lovely cover, how could you resist:

If the answer to that is “because I want a print copy and dear god international shipping now costs both arms and a leg,” don’t worry, a US edition is in the works. (As is an audio edition, if that’s your preferred narrative delivery method.) But look at that cover! You know you want it, and all the bloody grimdark vengeance within.

(Even if it’s a day late.)

The post Happy (belated) (UK) book day to me! appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 13, 2023

New Worlds: Saints and Miracles

Having talked about sanctification last week, now the New Worlds Patreon turns to the holiest people of all: saints! Comment over there.

The post New Worlds: Saints and Miracles appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 12, 2023

Another story sold to SMT!

I have sold another story to Sunday Morning Transport! This will be my third, coming out some time next year.

The thing that pleases me the most here is, this short story was originally supposed to be a novel trilogy. One for which I came up with the concept over fifteen years ago — but I didn’t sell it then, and now both the genre and I have moved on enough that I recently faced up to the fact that I’m unlikely to ever write it. For an assortment of good reasons . . . but it made me a little sad, because there were key beats in the concept I really liked, which can’t be transplanted to a different story without basically re-creating the thing I had good reasons for not writing.

And then, while I was being sad, I read some of Borges’ short fiction for the first time.

Which is how I wound up condensing that trilogy down into 2500 words of testimony from the interrogation of a character who was there for all the events of the novels I’m not writing! Not only did this let me keep those key beats, but it also let me skip the hard work of coming up with all the details of the clever, long-term plans laid by the characters; I can dispose of that in a sentence or two of “we spent years setting that up.” Win-win!

The post Another story sold to SMT! appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 10, 2023

I Should Sue My Boss

Continuing on from my post about how my work has increased . . .

Earlier this year someone posted to a writers’ group I belong to, asking how those of us who write full-time decide how much time to take off work.

Which rammed me face-first into the fact that I have no answer to that question.

Time . . . off . . . ? What is? I’m not kidding when I say I’d never in my life given real, meaningful thought to the matter. I have never worked at a conventional job, where things like “vacation days” and “sick days” and so forth might be a consideration: it’s either been summer stints, no more than three months at a stretch, or it’s been teaching jobs. Or writing, where I am my own boss . . . and when I stopped to take a look at how that’s going lately, I realized I should probably sue my boss.

See, at the beginning of this year, I decided to try using a spreadsheet someone had made that would track my output. I’ve never done that as a long-term thing; sometimes when I’m drafting a novel I’ll record my daily progress, but I chuck that once the draft is done. But I was curious, so I took the spreadsheet and modified it to have separate tabs for fiction and nonfiction, plus one that would add those together for my total wordcount. (The spreadsheet in question is set up to look like a calendar and has coding that changes the color of the cell depending on how much you wrote, hence me using what someone else had made — the bells and whistles were attractive.)

Thanks to this, I had a way of gauging how many days I’d taken off thus far in 2023. I couldn’t really measure time — whether I’d spent at least X hours on a given day doing work — and of course this was only tracking word output, plus the notes I’d added to cells when I spent the day doing something else in that “main work” category (e.g. copy-editing Labyrinth’s Heart instead of drafting The Market of 100 Fortunes). But in the absence of a better metric, I decided to count it as a workday if I’d recorded any words written or noted other main work. Undoubtedly that counted some days where all I did was spend half an hour revising and then posting a Patreon essay — but it also missed days where I spent hours catching up on work email or updating my website or doing one of the million other tasks that surround the main work. I decided to call it a wash.

So with that rule in hand, circa April I counted up how much I’d been working so far this year . . . and I did not like what I saw.

In January I took three days off. I don’t mean three days surplus to weekends; I mean three days. Counting New Year’s. Admittedly, it was crunch time, because I was having to draft one book, revise another, and copy-edit a third — that’s not quite normal working conditions. But crunch time was not followed by compensatory relaxation: in February I managed seven days off, but that’s still one less than the number of weekend days in the month. March saw me working three straight weeks with no break, whereupon I was done with the draft and fell over for a bit . . . by which I mean eight (not quite consecutive) days off, equal to the number of weekend days. So in the first three months of the year, I was a full seven days in the hole just by the metric of a five-day work week — let alone any notion of vacation or sick days or official holidays.

Things did not exactly improve from there. Over the next few months I attempted to make up for how the year had begun; the practical result of this was that I closed out the first half of the year a mere five days below the weekend line (still no vacation etc). In July I went on actual vacations, two of them . . . well, one and a half? ish? Because the second one was right before Alyc and I launched the Kickstarter, so it was in reality a working trip, me doing campaign prep from my hotel room in Hawaii, and it means I didn’t make up any of that lost ground.

And then August happened. With the Kickstarter. And all the book/campaign promo — I had a week where there was some kind of podcast or interview or whatever scheduled every single day. And I went to two cons.

I took one day off in August.

Which is why I spent as much of September as I could possibly manage on official, no-seriously-I-mean-it this-time vacation. In theory there’s a book I want to be writing on spec; the original plan was that I would launch into that as soon as I was done drafting The Market of 100 Fortunes, all the way back in April. My subconscious’ answer to that was you may go directly to hell, and looking at the data, I can see why. I didn’t manage to start it in May, either. Or June. And by July I knew there was no way I’d be able to draft fiction until the Kickstarter was in my rearview mirror; I managed, by herculean effort, to do one afternoon of revision on a project in August, but that was it. Then September rolled around and AHAHAHAH NO, we were not starting anything just yet. My concerted effort to Not Work netted me a glorious fourteen days of relaxation out of thirty . . . but thanks to the madness that was August, that still doesn’t get me back up to the “five-day week” line for the year. Vacation, above and beyond the basic idea of weekends off, is still out of reach.

Now, I recognize that in the grand scheme of things, my problems aren’t that bad. There are far too many people who have to work multiple full-time jobs just to make ends meet (if they even do). Or who work this hard while also dealing with health problems, child or elder care, or other obligations that demand a lot of their time and energy. But for my own particular situation, if I want to be able to go on working anything like effectively, something’s gotta change. The battery is draining faster than it’s charging.

Next post (probably final post) will be about what I’m doing to try and turn that around.

The post I Should Sue My Boss appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 6, 2023

New Worlds: Sanctification

New month, new theme! The New Worlds Patreon is pivoting back toward religion, with a look at what gets sanctified and how. Comment over there!

The post New Worlds: Sanctification appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 3, 2023

No Time Off for Good Behavior

Continuing on from my post about tracking the time I spend on work . . .

It used to be the case that while drafting a novel, I would write seven days a week. “No time off for good behavior” was my rueful motto: even if I already had 7K words thanks to some energetic days earlier in the week, I would still write on the weekend. Stopping, even for a day, meant a loss of momentum, my grip on the trajectory and shape of the narrative slipping a bit from my mind. So for the few months it took me to draft the book — three or four for most books; maybe five at the outside — I worked every single day.

That only applied to novel-drafting season, though. Outside those spans of time, I am not and never have been a “thou shalt write every single day” kind of writer. I can’t pivot directly from one book to a new one, or chain-smoke short stories so that I’m always actively working on something. I’d also spend stretches of time revising the book, of course, but I had months in between projects — months during which the next one would compost in my mind, prepping me for my next burst of work.

As near as I can tell, the last time that was true for me was 2016.

That year, I finished one novel (Within the Sanctuary of Wings), one novella (Lightning in the Blood), and one short story (“The Bottle Tree”). My short fiction production had been dwindling for a while, hitting its nadir that year — and since that was also the year we bought a house and moved into it, with 90% of the moving being done by me, I’m not surprised my overall production was low.

Starting in 2017, though, things changed. I began my Patreon: now I was on the hook for a essay every week. Only a thousand words or so, but I had to write it, revise it, and get it posted without fail. Also send out the weekly photo to my patrons, and the bonus essay for those at higher levels, and later I added topic polls and monthly reviews. Plus, of course, each year I had to reorganize the essays into a collection and revise the whole thing, essentially adding a 60K book to my annual production.

I also started to get back on the short fiction horse. Three stories in 2017, five in 2018, ten and four flash stories in 2019. I also started organizing my body of short fiction into collections through Book View Cafe in 2017; later I began producing print editions of those, doing the formatting myself, and going back to do the same for other works of mine, too.

I began collaborating with Alyc, putting the M.A. Carrick hat on my head right alongside the Marie Brennan one. I began writing for games: my L5R short fictions began in 2017, followed by microsettings for Tiny d6 and quest chains for Sea of Legends. In late 2019 I started teaching more, through an online tutoring program and workshops for Clarion West and Cat Rambo’s Writing Academy. I mentored through the Codex Writers’ Group and SFWA’s own program. I started actually cooking dinner sometimes rather than living entirely off prepared meals and takeout.

I added more. And more. And more.

To some extent I did this to compensate for the inevitable fluctuations in a writer’s income. None of those above bits brings in a great deal of money, but altogether it adds up to a meaningful amount. Each dribble, though, requires its own separate effort, its own time and energy, rather than the nice feature of novels where you write them and then they go on earning money (through royalties, foreign sales, etc.) without you having to invest much more in them.

By my rough estimate, I’m working about three times harder than I was in 2016. I don’t keep long-term records of how many words I’ve written each day, and such records would fail to measure all the writing-related program activities that go along with the words anyway, but that’s my best guess at the overall burden I’m carrying. And I’m definitely not earning three times as much money from it! What’s more, a lot of this is stuff that winds up having firm commitment attached; I can’t (easily) just drop a mentorship or my Patreon or a title I promised for BVC’s publication schedule without causing problems. Whereas before, the “bonus” stuff I did, like “A Year in Pictures” where I posted one of my photos to my blog every weekday for a year, weighed more lightly because it was 100% optional — and not jostling for space with twelve other things at the same time.

The upshot of all of this is, my time off from things that could in one way or another be called work has shrunk alarmingly. I like to be productive, but I also need time where I can allow that muscle in my mind to relax. Where I can let go, where I can watch TV with my household and not feel like I should also be dealing with e-mail or updating my sales records or doing work on the BVC website at the same time. Remember what I said in the last post about how often I was doubling up on two categories of work at once? Yeah. That’s honestly not good. The Inner Puritan may nod approvingly, but the Inner Puritan can go to hell.

For a while it felt okay. But this year? This year it has become very, very clear to me that it’s not okay. I can do that for a while, but I can’t do it forever. And so the next (and probably) final post of this impromptu series is going to unpack what I’m doing about it now.

The post No Time Off for Good Behavior appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 2, 2023

Books read, September 2023

Pursuant to yesterday’s post (which I’ll be following up on later), I tried to take some time off in September. Result: I read a lot, though some of these are quite short.

What If 2: Additional Serious Scientific Answers to Absurd Hypothetical Questions, Randall Munroe.

Follow-on to the first one, which I read back in January. By the nature of these books, you don’t need to read them in order — by which I mean both first book then second, and the contents of said books. They’re ideal for those moments where you have just a couple of minutes and don’t want to dip back into a narrative or a complex nonfiction discussion, because each question and its answer are at most a few pages. I think this volume made me laugh less frequently than the first one, but that may not have been the book’s fault; I read this toward the end of the Kickstarter I was running and had virtually no brain to spare for anything. Brief discussions of what would happen if you filled the solar system with soup out to the orbit of Jupiter were about my speed.

The Enterprise of England, Ann Swinfen.

Second book in her Elizabethan series, focusing on (this is not really a spoiler since it’s right there in the title if you know the period) the threat of the Spanish Armada.

It got off to something of a rocky start, as Swinfen appeared too determined to give you a fleeting tour of key events around that time: the death of Philip Sidney, Drake’s raid on Cadiz, the loss of Sluys, none of which the protagonist is involved in. I also continue to feel like this series is less well integrated than Swinfen’s Oxford Medieval Mysteries. There’s Kit’s work as a doctor, which she keeps getting dragged away from in order to do espionage instead, and then it feels like Swinfen really likes the Elizabethan theatre scene, but instead of coming up with a different series about that, she crams it into the corners of this one instead. Honestly, theatre + espionage would have combined quite well — especially since Marlowe shows up briefly here (in a really negative light, wow do I get the impression Swinfen thinks poorly of him). But the medical stuff, while interesting, just does not play particularly well with the other bits.

Having said that, this book found its feet much better once it settled into Kit and her father caring for the survivors of Sluys, then shifts reasonably well into espionage gear when Kit is sent to the Low Countries to try and discover who there might be betraying the English and Dutch to the Spanish. There’s a slightly contrived encounter with the Armada toward the end, when the ship carrying Kit back home gets caught up in the hit-and-run fighting in the Channel, but it didn’t feel too jarring. I will continue to read, despite my feeling that this isn’t as well-knit as the Oxford series.

Lonely Castle in the Mirror, Mizuki Tsujimura, trans. Philip Gabriel.

Bestselling Japanese novel; in terms of subject matter it probably counts as YA or MG (based on the ages of the characters), but since it wasn’t written for the English-language market, it doesn’t partake of any of the standard tropes and dynamics of those categories. The narrator, Kokoro, has stopped attending school because of bullying — and I find it interesting that, apart from one frightening incident (where a pack of girls surrounded her home and shouted for her to come out), the bullying doesn’t come across as super awful. It doesn’t have to be super awful; what matters is that it’s triggered Kokoro into such a pit of depression and anxiety that even the simplest things send her spiraling.

Which I have to admit sometimes made for a frustrating reading experience. The central concept is that Kokoro’s mirror lights up and when she touches it, she’s pulled through into a strange castle run by a little girl in a mask who calls herself the Wolf Queen. That girl has chosen a group of children to search the castle for the key to the Wishing Room; whoever finds the key and enters the room will have one wish granted, and after that they’ll all be kicked out forever. Because of Kokoro’s depression and anxiety, though, her immediate reaction to this is to run away; although she can go to the castle for a certain amount of time every day (and her parents, who both work, won’t know she’s gone), her fears over how awkward it will be if she encounters one of the other kids/the idea that they’re all there hanging out together without her/etc. combine to paralyze her into inactivity. It’s the inherent challenge of having a reluctant protagonist: the reader is here for the cool thing that’s going on, so a character who tries to avoid the cool thing and all the other characters is going to be frustrating.

Kokoro does eventually start engaging with the plot, of course; otherwise there would be no book. For quite a long time, the focus is more on life in the castle and the dynamics among the kids than on the macguffin of the key and the Wishing Room, but that’s fine. All of them (save one odd exception) are avoiding school for one reason or another, and in many ways that’s the real story here, as they gradually open up to each other and get past all the defenses and annoying habits that push them apart. For a while I wondered if the key and the wish would wind up not even mattering at all. But the fantastical promise that set everything in motion does pay off in the end, and while I correctly guessed at a couple of the things going on, there was one vital element that took me by surprise, in a very good way. Recommended if you’re not going to be either triggered or driven to distraction by a character whose mental health difficulties form so much of a roadblock early on.

Another Life, Sarena Ulibarri.

A brief novella set in a climate apocalypse future, but focusing more on the efforts of one community to find an alternative way of life. I very much appreciated that while the residents of Otra Vida actively seek to create a better society, it’s not utopian in the shallow sense of being perfect (or in the sense common in science fiction where the shallowest scratch on the surface of that utopia reveals a howling dystopia underneath). In particular, one of the central conflicts here focuses on the office of the Mediator, which the founders of Otra Vida hoped would work as a way to arrange conflict resolution without leaning on top-down enforcement. The main character, Galacia, has been the Mediator from the start of the settlement . . . and that’s becoming a problem, both because she’s not without bias — no human can be — and because her long occupation of the role means she’s acquiring a kind of authority she was never meant to have. In that aspect it reminded me a bit of B.L. Blanchard’s The Peacekeeper; I had significant problems with the plot of that latter book, but I very much appreciated its attention to how even a restorative rather than retributive system of justice is still flawed and can still fail the people it’s meant to help.

Apart from the worldbuilding of this settlement in that future, the big speculative element here is the idea that people genuinely do reincarnate, and a new process has been developed that lets you discover who you were in your most recent life. Since this is in the cover copy, it’s no spoiler to say that Galacia discovers she’s the reincarnation of Thomas Ramsey, the Big Villain of the climate apocalypse — but there were two aspects of that plot I particularly enjoyed. One is that, while she has a particularly shocking discovery, she’s not the only one kind of screwed over by this new process; there’s a minor side note of a gay couple who discover they were father and son in their previous lives. It shouldn’t affect them now — they’re not related in this life — but it causes a major disruption in their relationship. And the other thing I really enjoyed was the acknowledgement that, however much Thomas Ramsey may have caused massive problems back in the day, it’s simplistic to paint him as the cause of the apocalypse; the issue was far larger than he was, and the records that survive of that time may not be wholly objective.

And fundamentally, that plot lands on a theme I really like, which is the question of how long you can hold someone accountable for past crimes — particularly in contexts like reincarnation or immortality, where it’s not just what they did forty years ago but four hundred years or literally in another lifetime. I’ve been rewatching the Highlander series recently (or, to be more precise, cherry-picking out Methos bits to rewatch), and it builds a really great thematic arc on that topic across a scattered range of episodes. So I was always a good audience for that aspect of the story, even if near-future post-apocalyptic SF is not usually my jam.

Living by the Moon: Te Maramataka a Te Whānau-ā-Apanui, Wiremu Tāwhai.

Another book my parents brought back from their trip to the other side of the planet, but this time not a collection of folktales. Instead this is a slim volume about how the Māori of a particular tribe traditionally measured the cycle of the moon, and then how they shaped their hunting and agricultural cycles around it. It’s very specific to not just an environment but a location, which is an aspect I think we urbanites often underestimate.

Deep as the Sky, Red as the Sea, Rita Chang-Eppig.

A novel based on the life of the female Chinese pirate I’ve mostly seen referred to as Ching Shih, though according to Wikipedia she’s also called Zheng Yi Sao, Shi Yang, Shi Xianggu, and Shek Yeung — that last being the name used for her in this story.

This reminds me a bit of both Iron Widow and She Who Became the Sun, not only in its connection to Chinese history, but in its willingness to take a warts-and-all approach to its protagonist. Chang-Eppig does not attempt to sugar-coat Shek Yeung’s behavior; although the novel credits her with the ban in the pirate fleet against raping female captives (which I’m given to understand probably didn’t originate with her), it doesn’t shy away from representing her as utterly willing to behead those who challenge her authority, manipulate those who could be of use to her — not infrequently to the detriment of her tools — and otherwise act with the ruthlessness required to keep a massive fleet of pirates in line. At the same time, it doesn’t just treat her as a monster, either: Shek Yeung knows her behavior is frequently not admirable, but either doesn’t see an alternative or is simply too tired and ground down by the challenges of her life to do any differently.

That same ambivalence extends well beyond Shek Yeung herself. The novel picks up at the point where her first husband, here called Cheng Yat, has just been killed. Under his leadership, Shek Yeung had command of half their fleet, but in order to keep from losing her position, she’s forced to swiftly marry Cheng Yat’s successor, Cheung Po. Both of them owe their power and wealth to Cheng Yat; both of them were also kidnapped away to sea and raped by him (Shek Yeung in the context of prostitution, but still, that’s not exactly a great example of consent). As a consequence, they both have profoundly mixed feelings about the man they’d grown so close to.

Technically there’s a central conflict here, in that the emperor has a new minister, Pak Ling, who’s finally posing a real threat to the alliance of pirate fleets that have been ruling the South China Sea for so long. But really, the novel is more concerned with following Shek Yeung through this stage of her life, as she first secures her position in the fleet alongside Cheung Po, then faces the loss of that entire world to Pak Ling and the encroachment of various European powers. It’s a mildly fantastical tale, in that the goddess Ma-Zou (Mazu, other forms) may have spoken to Shek Yeung once or twice, sometimes prayers seem to be granted, omens may be real . . . but it’s right on that line where the narrative could possibly be just depicting the belief of the faithful, without objectively stating that there is supernatural intervention. (There are also brief chapters interspersed throughout that tell various stories about Ma-Zou, which is helpful for a reader like me who’s not familiar with her mythology.)

Like Iron Widow and She Who Became the Sun, this is a novel deeply concerned with the problem of sexism, but in place of Iron Widow‘s incandescent anger it has a kind of weariness. Shek Yeung doesn’t expect to change anything except her own circumstances, and she’s extremely aware at all times of how precarious those are. It makes for a rather melancholy novel in the end — especially since it doesn’t leap for alternate history at the finale; things play out as they did in history — but a very well-written one, on the level of prose and so forth. I think my biggest complaint is the pacing at the end, which skips off the surface of several major sea battles and then arrives very abruptly at the concluding negotiation with no connective tissue between the former and the latter. The book as a whole, though, I very much enjoyed.

Road of the Lost, Nafiza Azad.

This one managed to hook me within a page just on the basis of voice, which I wasn’t expecting. I’d been a little iffy on the premise, simply because there’s a quasi-Celtic basis for the worldbuilding — the protagonist, Croi is a brownie (well, sort of), and there are pixies and the kingdoms of Talamh and Tine and other Irish words — and I simultaneously love Celtic-based stuff and have seen enough of it, much of it done poorly, that my starting mindset tends to default to “skeptical.” But I liked the voice, and I liked Croi even when she’s being prickly, and I was intrigued by where the plot was going: although Croi seems to be a brownie, that turns out to be a powerful glamour placed on her by an unknown power using magic that should be lost. Croi, who’s lived most of her life on the fringes of human society with no faerie company but a woman she calls the Hag, has to travel to the Otherworld and find out what her true nature is.

Naturally, she encounters other people along the way — but those people drag her piecemeal into a much larger plot about the politics and metaphysics of the Otherworld, one I found fairly engaging. My complaint here, insofar as I have one, is that this feels very much like the first book of a series, yet I can’t find any sign of a sequel coming out. We end with some revelations and with one character’s final words to the protagonist being “come find me,” but things are very far from resolved. I hope there will be a second book, and this isn’t a case of the publishing industry axing something half-finished because sales weren’t good enough.

The Kuiper Belt Job, David D. Levine.

Disclosure: the author is a friend, and sent the book to me for blurbing. Well, to me and Alyc, on the grounds that it’s caper/heist-y and that might appeal to readers of M.A. Carrick, though this book — as the title suggests — is science fiction.

I inhaled it in about a day flat. The structure is interesting: the story centers on a group of thieves that call themselves the Cannibal Club (no cannibalism involved; it’s just a name one of the characters thought sounded cool), who broke apart years ago after a job went wrong. The story alternates between segments showing you that earlier job, and segments that bring the surviving crew back together for a new challenge — with each of those latter bits 1) being from the perspective of a different character and 2) involving smaller heists necessary to get the next person on board or out of whatever situation they’re trapped in. This allows for a variety of challenges along the way, and each one has a distinct flavor.

You also get a really interesting tour of the solar system! There’s a technology here, the skip drive, that lets ships go fast without instantaneously arriving wherever they want in the solar system, so travel time is still real without making the titular job, all the way out in the Kuiper Belt, a years-long undertaking. On the way there, the story hits a variety of locations, many of which are off the standard beaten path of fiction (at least the fiction I read — admittedly my SF consumption is relatively small). Like, I learned about trailing trojans from this novel! So if this is your kind of thing, I highly recommend it, and you will probably see a blurb from M.A. Carrick somewhere in the marketing unless David decides not to use it.

Worrals Flies Again, W.E. Johns.

Third of this 1940s series about a female WAAF pilot during World War II, and my god Captain Johns could that title have been any more bland? I genuinely will have to keep referring to the Wikipedia page to know what order these books go in, and to my own posts to remember which plot goes with which name.

In this one, Worrals and her best friend Frecks get dispatched to a chateau that’s a collation point for intel from the French resistance. The idea is that the tiny little plane they use, which has foldable wings, can be hidden in the chateau’s cellars; then, if an urgent message comes in, they can fly it back to the U.K. rather than using radio or pigeons, both of which have significant problems with reliability. As a side note, this series does a great job of really making me understand just how close the British and French coasts are to each other, because of the ease with which characters can fly back and forth. (Well, “ease” so long as you don’t take into account flak guns and enemy planes.) I grew up in Texas, where everything other than More Texas was very far away; it croggled me when we were in New York City and my parents went to another state for dinner. Travel within Europe gives me much the same feeling of “buh? how?”

Anyway! These being pulp adventures, naturally the above plan goes wrong immediately. There are Germans lodging in what should have been a nearly unoccupied chateau; there is an urgent message, but it’s already in the hands of the Germans. Everything I’ve enjoyed about this series before continues, especially the way that Frecks, instead of being the Bumbling Comic Relief Friend, gets her moments to shine. And the relationship between Worrals and a fellow pilot, Bill Ashton, continues to fly in a zone I find very pleasing: there’s attraction between them, but both of them put the war and their duties first, and while Bill is sometimes helpful, it’s never in a “swoop in and save the ladies” kind of way. In this book Worrals has to rescue him from captivity, less through overt derring-do than through clever deceit. One male villain briefly cross-dresses, and I was delighted that this did not come across as hinting at Teh Evul Gayz; it felt like a tactical move by a chillingly pragmatic man, nothing more.

Two minor quibbles for this book, neither of which ruined my enjoyment. One is a particular side character who winds up being fine in the long run, but may register as an awkward stereotype at first if you don’t know where the story is going. (I was spoiled for that because of Rachel Manija Brown’s post about this book, but I didn’t mind.) The other is one bit of drama that felt a little too over the top for me — you know instantly that what seems to have happened can’t possibly be true, so then it’s just a matter of waiting for the explanation, which felt a bit too convoluted once it arrived. But whatevs, these are still rip-roaring Nazi-thwarting feminist adventures, and I’m gonna keep reading them whenever I want a couple of hours of delightful fun.

The Curse of Capistrano, Johnston McCulley.

This book was eventually republished under the name The Mark of Zorro, after the film with that title made the character a household name. Yes, gentle readers, this is the very first incarnation of Zorro!

It’s kind of fascinating to see where it does and does not match the versions I’ve seen before. No real origin story here, except as briefly described by Diego at the end; we start out with Zorro already a notorious figure in California, terrorizing corrupt soldiers and aiding those they oppress. The story’s omniscient narrator doesn’t tell you Diego is Zorro — there’s just this dashing masked outlaw (full-face mask, unlike the cinematic depictions) and this incredibly effete nobleman, and I wonder if audiences at the time knew right away they would be the same person, or if that trope was still new enough in 1919 that the connection wasn’t shriekingly obvious to everyone. Interestingly, though McCulley went on to write a ton more about this character, it’s clear he didn’t have that intent from the outset; this book ends with Zorro publicly unmasking as Diego and the corruption being dealt with and everyone living happily ever after, the end. (The introductory matter in my copy, which includes a brief biographical sketch of McCulley, notes that every adaptation ever and McCulley’s own sequels just . . . pretend that ending never happened. No explanation, nothing to see here, just move along.)

Of course, it does also have its flaws. The narrative never misses a chance to remind you that the tavern landlord is fat as well as greedy, and there is definitely a certain ideal of masculinity being promoted here (albeit one that involves musical talent and other such elements). Indigenous Californians appear only as generic “natives;” none of them have names, I think only one gets like a single line of dialogue, and their agency is basically limited to getting the hell out of the way when they see that shit’s about to go down. Zorro defends them, but only because they epitomize the helpless, oppressed masses, and the work of the friars in their missions is presented as unambiguously good. Women are not quite as backgrounded as the natives are, but there are only two in the story: Lolita Pulido, the young woman courted by both Diego (with extreme ineptitude) and Zorro (much more successfully), and her mother. I will say, though, that after I assumed Lolita’s sole agency in the narrative would be refusing to marry Diego even though it would save her family from political and economic peril, she surprised me by proactively escaping the bad guys and displaying virtuoso riding skill — so that was a pleasant turn.

On the whole, I’d class this under “historically interesting but not so great you should rush out to find it” (i.e. below what I shall now call the Worrals Line). What I bought was the Summit Classic Collector Edition, and while I appreciated the introduction and the context given there, I really wish they’d been more aggressive about cleaning up the obvious typos in the text, rather than piously presenting their approach as preserving the author’s intent. I’m betting you could find this on Gutenberg, if you want to glance at it without committing money to the enterprise.

The Foul and the Fragrant: Odor and the French Social Imagination, Alain Corbin, trans. Miriam L. Kochan, Roy Porter, and Christopher Prendergast.

I have no recollection of where I saw this book recommended, but it makes for a hell of an odd read.

The focus here is much more on “the foul” than “the fragrant,” i.e. far less about perfume and such than I expected (though there is some discussion about how the fashions around that changed over time). Instead the central thread is, essentially, the deodorization of life, specifically in France, from roughly the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries: how ideas and attitudes toward stench changed, leading us to increasingly try and eliminate from our surroundings the odors of urine, feces, sweat, decay, mud, and more.

What made this interesting to me was the intense glimpse into “the past was a foreign country.” You get a very real sense of how those smells were taken so much for granted that they kind of didn’t bother people — in fact there’s one old woman mentioned in here who commented, post-Revolution, about how those smells made her nostalgic for the days of the ancien régime. You also get a tour of historical science, as scholars tried to figure out what smells even were, how air operated, how disease spread, and so forth. As gobsmacking as it is to think they believed that merely agitating air or water was enough to purify it, they did: something something restore the elasticity of the air, totally not how any of that works. And also too much water was bad because it relaxed the fibers of the body and made you vulnerable. A whole, completely alien understanding of the physical world, which led to an astonishingly filthy world where everyone was very convinced that cesspool clearers were robustly healthy because of their exposure to filth, and that’s why you should spread it in the streets to combat plague.

I suspect I would have gotten more out of this if I were at all conversant with French literature, because Corbin frequently cites it to track changing ideas about and attitudes toward both good and bad smells. I did, however, follow the parts about how hospitals, prisons, and ships were testing-grounds for new approaches that later got rolled out to the general populace (including teaching people new techniques for taking a crap; schoolteachers were put in charge of this), and how the assumption that X group naturally stank shifted from occupation and/or place of origin, to economic class, to race. So basically, it’s a whole lotta insight into historical mentalities of a sort very different from our own, and really fascinating so long as you’re willing to cope with extended discussions of gross bodily matters.

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens: How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire, Jack Weatherford.

So, I know very, very little about Mongolian history. If you’d asked me to name important women from that culture and time, I would have said, “uhhh, Khutulun?” and that would have been it.

Boy howdy is there stuff I was missing.

The subtitle is rather a misnomer. Genghis Khan’s daughters, and also his daughters-in-law, did not “rescue his empire;” it collapsed with astonishing speed, due in no small part to the incompetence, rivalry, and cruelty of his sons, which included a truly massive backlash against the women who held power. I suspect it’s supposed to refer, in a very broad sense, to Manduhai, who married one of Genghis Khan’s few surviving patrilineal descendants and pulled the Mongols back together into a coherent state several centuries later, but that’s far from the empire he himself had created.

Leaving the inaccuracy of the title aside, though, this was absolutely amazing to read. Weatherford lays out very clearly how much power Genghis Khan put in the hands of the women around him, in ways that (in the afterword) Weatherford admits he himself wouldn’t have believed if someone had handed him a book like this to read. The image has to be assembled from fragments; someone in the past literally cut a section out of the text now called The Secret History of the Mongols, leaving behind only one tantalizing phrase that suggests the missing bit had to do with the Great Khan’s daughters. But we know that the women who married his sons were given the title of beki (usually only given to princes) or khatun (essentially “queen”), and served as important diplomatic representatives of their peoples, while his daughters were also called beki and were, in their nuptial edicts, explicitly sent to govern the peoples they were married off to. The sons-in-law, meanwhile, merely got a title that meant “son-in-law” and were given positions of honor in Genghis Khan’s own guard . . . which 1) took them away from their homelands and 2) tended to shorten their life expectancies by a lot. His will left huge swaths of the Mongol Empire in the hands of women, whether his wives or his daughters.

Unfortunately, of course, none of that lasted. And it’s not all on the shoulders of the men: the women also fought to extend their power (or that of their husbands/sons), with a lot of bloodbaths as a result. Still, things like the mass gang rape of four thousand women, followed by selling off the survivors — in direct and flagrant contravention of laws laid down by Genghis Khan — were certainly the fault of guys like Ogedei. It was basically a long downhill slope from there, with a trough in which the power and agency of ruling women was reduced to things like eye-popping ruses designed to keep a male Borijin clan baby safe from the people trying to exterminate Genghis Khan’s lineage from the world, until things pick up again with Manduhai. But there’s really intriguing information here on Mongolian culture and what you could almost call a fluorescence of thirteenth-century feminism, in ways that make me really crave an alternate history fantasy in which the ideology then managed to take root and go on holding power.

Alchemists, Mediums and Magicians: Stories of Taoist Mystics, trans. and ed. Thomas Cleary.

I don’t think I realized, when I bought this book, that it’s a translation of a fourteenth-century hagiographic Chinese text, rather than a modern work on the topic. As such, it wasn’t as interesting as I’d hoped: the biographical sketches here (organized by dynasty and labeled with grouping terms like “Taoist Character” or “Taoist Influence”) range from a couple of paragraphs to a couple of pages, and it isn’t long before you start to see the formulaic elements they share.

They’re not all identical; for starters, there’s a distinct bifurcation between the Taoists who served in government and used their wisdom to improve their respective rulers, and those who found more or less eloquent ways to phrase “no, fuck off” when begged by emperors and kings to come serve. In the aggregate, the formulas are moderately useful from the perspective of getting a feel for Taoist beliefs and ideology, e.g. the various ways their deaths are described: some leave behind fragrant and undecaying corpses thanks to their Taoist cultivation, while others are as light as a feather and some leave behind only their clothes with the sash still tied, thus proving their bodies were sublimated right out of physical existence. But I had to take lots of breaks as I read through this, because otherwise my eyes started to glaze over.

One thing I noted: while none of the individuals who get biographies in here are women, there are a handful who show up as immortals in the tales, usually as instructors to the men. Also, there are a lot of footnotes mentioning other books of Cleary’s; if (let’s be real, when) I decide I want to read more about historical Taoism, I suspect his corpus of work would be a useful place to start.

Myths and Legends of the Navagraha: The Nine Movers of Destiny in Indian Astrology, Nesa Arumugam.

One of the random things I’m curious about is non-Western astrology and how it’s set up. This turns out to be much less an answer to that question than I’d hoped; instead the emphasis really is on the myths and legends about the relevant deities. Which I didn’t mind! Though the stories here do naturally bring up figures I know better, like Shiva and Vishnu and Laxmi, the only one of the Navagraha I felt at all familiar with was Surya, and I at least recognized the name of Chandra. The rest were new to me.

And you do get some information on the operation of Vedic astrology, if only because the selection of the Navagraha tells you some things. In addition to the usual suspects of the Sun, Moon, and five visible planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn), you get two deities representing, not celestial bodies, but the ascending and descending lunar nodes — the places where the orbit of the Moon crosses the ecliptic. That right there is fascinating to me! Arumugam also touches on the associations each deity has in astrology, albeit only briefly.

But that’s fine, because the stories were pretty great all on their own. Arumugam feels no need to try and nail mythology down to a single consistent tale; she freely relates contradictory versions from the Rig Veda and the Puranas, along with the occasional folk belief. I also appreciated the periodic comments on the difference between South Indian (specifically Tamil) and North Indian narratives, practices, and beliefs, since I know that what I’ve read in the past has tended to have a distinctly northern skew. And man, once again I am reminded of just how genderqueer Indian mythology can be: not only do you get the story I’ve heard before of Vishnu taking female form as the beautiful Mohini to trick the asuras, but one of the Navagraha, Budha (Mercury, and not to be confused with Buddha-of-Buddhism), is queer through and through, sometimes taking male form and sometimes female in response to what sex their spouse Ila/Sudyumna is at any given moment. It’s really intriguing stuff.

Embracing Uncertainty: Future Jazz, That 13th Century Buddhist Monk, and the Invention of Cultures, John Traphagan.

I . . . really have a hard time summarizing this book, which my sister gave to me as a birthday present. Traphagan is an anthropologist who’s spent much of his career studying Japan, but his earlier background is in philosophy, and also he plays jazz drums, and all those things kind of smush together to make some points about . . . look, this makes it sound like the book is bad, and it isn’t. It’s just so much a semi-rambling set of thoughts Traphagan has that attempting to encapsulate any core is difficult. He talks about cultures as being kind of like the lead sheets jazz musicians use, and how Dōgen (founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan) diverged from earlier Buddhisms, and what Zen really is like in Japan (as opposed to how it gets represented in the West), and how contemporary America is miring itself further and further in binary oppositions which Dōgen’s philosophy counters, and how we’d all be better off if we accepted that the world is uncertain, that we can never make it certain, and so we must embrace the jazz improvisation that is life.

Or something like that. In a bizarre sense, I think the best way for me to comment on this book is to lean into how I talk about Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash. My pitch there is usually “if computer hacking, neurolinguistics, and Sumerian mythology sound interesting to you, then you might enjoy this book;” here it would be “if anthropology, Zen Buddhism, and jazz music sound interesting to you.” I don’t think the subtitle of this book is great, but also I don’t know what I would use in its place, and hey, at least this one has the virtue of “does what it says on the tin.”

The post Books read, September 2023 appeared first on Swan Tower.

October 1, 2023

Timey-Wimey Metrics for the Writing Life

A little way into the covid lockdown, I spent two weeks tracking how I use my time.

My reason for doing this was the realization that . . . I really didn’t know. Specifically, I didn’t know how hard I was working at my job of being a writer. On the one hand, part of me felt like the answer was “pretty hard;” on the other hand, my inner puritan — which is always ready to doubt whether it even counts as work if you enjoy what you’re doing — really likes to tell me I’m being a slacker. The only way to judge which one was right (if either) was to actually pay attention.

Of course, any such tracking runs immediately into the challenge of finding where the boundaries of my job lie. My sister has a story about her college philosophy professor who was late to class one day because he was busy thinking; while on the face of it that sentence sounds ridiculous, the truth of it is that some kinds of work can indeed take place entirely inside your skull. And that doesn’t look like work, does it? I’ve told my husband that if I’m lying across the bed staring at the ceiling, that means I’m working, and he believes me. But sometimes it’s hard for me to believe me. And often the signals of me working aren’t so obvious, because what’s going on is that I’m driving somewhere or I’m in the shower or I’m otherwise engaged in some non-work task . . . but my mind is bubbling away, combing the tangles out of a plot or composting different elements until an idea sprouts out of them.

How do I track that, when half the time I’m not even really conscious of it going on?

For this particular project, I didn’t really try. Instead I tracked more observable categories of activity, which were (in descending order of how much my brain wants to accept that they’re “work”):

* Main work. Which is to say, drafting or revising a draft, the stuff that comes to mind first when you think about What a Writer Does. I included writing Patreon essays in this category, along with going over copy-edits and other such publication tasks.

* Writing-related program activities. I borrowed this phrase from the late Jay Lake, to cover all those things that are actually part of the job but not, y’know, the writing part. Answering email, updating my website, submitting short fiction, anything administrative in nature.

* Continuing writing education. A phrase I borrowed from my sister, for whom “continuing legal education” is part of the job. If I want things to come out of my brain, I have to put things in. So, reading a book, be it fiction or nonfiction? That’s CWE. I can’t remember (this long after the fact) whether I counted all movies and TV as well, but I definitely counted documentaries, as I was in the middle of a spate of those at the time. I need both narrative and material out of which narratives could be made for a balanced creative diet — and no, it can’t just be material I already know I need, like research reading for a planned story. Those stories only get planned if I have the ideas for them in the first place, and rather a lot of my ideas come out of me saying “this looks interesting” and picking up a random book.

* Domestic labor. This was where Feminism Brain got to put a muzzle on Inner Puritan. Cooking and cleaning are work, damn it; they’re just work mostly done on an unpaid basis. So I tracked them, too, even though Inner Puritan kept making muffled, squawking noises in the background.

* Self-improvement. The most borderline category for “work” purposes. This mostly covered exercise (because when you have a sedentary job, the care and maintenance of your meat sack is pretty important), meditation, and Duolingo practice (Japanese, which does play into my work — come to that, so does the meditation).

Categories did overlap, of course, and I did my best not to double-count my time. When I watched a lecture on symbolism in Chinese art while riding the stationary bike, I put part of that time under CWE and part under self-improvement. The very fact of tracking no doubt altered my behavior (observer bias!), and I can’t swear my tracking was always precise, since sometimes I forgot to log when I had started or finished a thing. But I did my best.

What did I find?

* Main work. I did not do this every day (no, I’m not a “you must write every! single! day!” writer), and of the categories, it’s the one most likely to fluctuate depending on where I am in the book cycle. On the days I did write, I averaged about an hour and fifteen minutes; counting the days I didn’t write, it drops to forty-five. Those numbers would be a little lower if I hadn’t been sent some copy-edits in the last two days, since I had a compressed deadline for getting those done and therefore spent four or five hours each day hammering that task. But on the whole, the results feel about right: if you’d asked me beforehand how much time I thought it took me to do my writing each day, I would have said “maybe an hour or so, unless it’s going really badly.”

Viewed from the Inner Puritan angle, though, this number is shocking. “Really? This is the core of your job, and you only spend an hour on it per day — and not even every day?” But the thing is, it has to be that way. For starters, main work generates writing-related program activities, so the more of the former I do, the more the latter will try to eat my life. And even if I had an assistant to deal with all of the WRPA . . . creative output is not infinite. I can’t consistently spend more time working on a single project because I will outrun the pace at which I can think my way through it (remember, that “general cogitation” category wasn’t tracked here). And I can’t just flip a switch to work on something else instead; while it’s sometimes possible for me to draft a short story alongside a novel, I can’t always manage that, and I cannot draft more than one novel at a time. Patreon writing, yes, but other fiction simultaneously is tough, and trying for it consistently would have detrimental results. So there are limits to how hard I can push on this front.

* Writing-related program activities. These I did much more consistently (almost every day), and for more time — a little under two hours a day. On average, WRPA and main work were in a 2.5:1 ratio to each other, and that’s with the copy-edits spiking the latter number in the last two days. Saying in general that I spend three times as much of my day on administrative matters as I do on the core part of the job sounds about right. You start to understand why some writers hire assistants . . . though I’ll admit, I have a hard time envisioning myself letting things go into someone else’s hands like that.

* Continuing writing education. Virtually identical to the WRPA numbers. My notes on those numbers, though, show that when this covered me watching something on the TV, it was very often doubling up with some other task, usually WRPA. Like I said above, I didn’t double-count the time — half got logged for CWE, half for WRPA — but it’s still instructive to know. This number surprised me by how high it was, and boy howdy did the Inner Puritan want to jump on it, especially when I was not doing something else productive at the same time. But: I need this. It is, in fact, a key part of my job. I read a lot more in 2020, thanks to the start of the pandemic, and also I wrote far more short fiction than usual. They’re not unrelated.

* Domestic labor. Just under an hour each day on average. Mostly spent on cooking dinner, with some amount of cleaning in there. (I would make a very bad 1950s housewife.) I should note that this number is lower than it might otherwise be because certain tasks (washing dishes and doing laundry) are more my husband’s bailiwick: an important point, because even in supposedly egalitarian households, there’s still a tendency for women to take on more of the domestic labor. I do think I do more of it than he does, but I also have a job where I can perform the thinking portions of it while sweeping or whatever. And he does more of this work than many men, which is reflected in the lowness of this number.

* Self-improvement. 45 minutes a day on average, generally fluctuating between 60 (if I rode the stationary bike) and 15 (if I didn’t).

And when I took these numbers and crunched them all together . . .

It turns out that I worked about forty hours a week, if I leave self-improvement out of it. (With SI in, it was a bit over 45.)

So: I was neither working myself to the bone, nor being a total slacker. Neither of my bifurcated opinions at the start were quite correct. It starts looking more like the slacker end if you put some sarcastic tildes around CWE, because admittedly, that does heavily overlap with leisure. But that thing I said at the start, about how there are few if any clean boundaries on this job? That’s true not just when it comes to thinking time, but also reading/watching time. No lie, I got a story idea off playing Fire Emblem: Three Houses. If I don’t allow CWE to “count” in my sense of how I approach my job, I’ll start de-prioritizing it, which means I’ll do less of it, which means I’ll be starving my brain of inputs. I can’t let it be all I do (at least, not for extended periods of time); I do need to perform actual main work, and then the three-times-as-much WRPA that produces. But looking at the numbers, the balance feels okay.

. . . with one caveat. Which will be the subject of an upcoming post, because this one is already long. But if you want a hint, it involves a phrase that’s been conspicuously absent until now:

Time off.

The post Timey-Wimey Metrics for the Writing Life appeared first on Swan Tower.

September 30, 2023

The Shining Moon Podscast

I have been incredibly remiss in posting about this!

An online friend of mine, Deborah L. Davitt, recently started up a new podcast called “Shining Moon: A Speculative Fiction Podcast.” She’s got a really interesting format; each episode gathers together a few writers to discuss first a topic, then their own stories that relate to the topic, then someone else’s story that similarly fits the theme.

I’ve been on two episodes so far, hence being incredibly remiss in taking this long to mention it. (I blame the fact that I was first running, and then recovering from, the Kickstarter.) The good news is, that means you now have multiple episodes to sample! My two thus far are “Literary vs. Genre” and Alternate History vs. Secret History — I swear, they’re not all framed as “X vs. Y;” I’ll be on one about worldbuilding about a month from now. There are two episodes on translations and writing in English as a second language, one on hard SF, one on game writing, one on speculative poetry; there’s also one on “Reading and the Working Writer,” as the podcast also touches sometimes on the life of a writer as well as the craft itself.

If you are someone for whom podcasts make up part of your media diet, I highly recommend this one! Even if you’re not a writer yourself, you might find interest in hearing people dissect different angles of the speculative fiction genres.

The post The Shining Moon Podscast appeared first on Swan Tower.

September 29, 2023

New Worlds Theory Post: Unfortunate Implications

As many of you know, when there are five Fridays in a month, the New Worlds Patreon devotes the fifth one to a theory post! This month we’re looking at the unfortunate messages your worldbuilding may send, whether you intend it to or not — comment over there.

The post New Worlds Theory Post: Unfortunate Implications appeared first on Swan Tower.