Scott Berkun's Blog, page 80

October 20, 2010

Interview: man who owns only 15 things

Well known start-up founder and conference organizer Andrew Hyde (@andrewhyde) recently decided to sell most of his worldly possessions. He currently owns only 15 things. Look around your office or home, I'm sure you can see more than that number of owned items around you right now. I bet some of you have nearly 15 items on you, between clothing and what's in your pockets.

Well known start-up founder and conference organizer Andrew Hyde (@andrewhyde) recently decided to sell most of his worldly possessions. He currently owns only 15 things. Look around your office or home, I'm sure you can see more than that number of owned items around you right now. I bet some of you have nearly 15 items on you, between clothing and what's in your pockets.

I interviewed Andrew about his motivations and experiences as an American with so few things.

SB: Given our hi-tech, gadget obsessed, culture, minimalism is not the typical lifestyle a young American would be expected to pursue.. How do you get interested in minimalism and what motivated you to make this change now?

AH: I dabbled over the last few years by taking a small backpack on 3 or 4 day trips. I was shocked in how much stuff I had. Even when I had packed my apartment, I was still shopping for more. It wasn't about need anymore, it was just habit. Realizing that changed the way I looked at buying stuff. I just stopped.

I remember reading a post by Fred Wilson with the message of "when was the last time you didn't spend any money in a day?" That made me think. I experimented from those thoughts. I left my wallet at home to see how I would 'get by.' Turns out, everything I spent cash on was pure comfort goods, and I could a week without spending cash besides groceries. My regular coffeeshop was more than understanding if I forgot my wallet, so were my coworkers and friends. It created a non confrontational way for me to really start aggressively saving.

This whole experience has taught me something very simple: debt kills dreams. Debt is cash, things and fear.

In one my favorite films, Fight Club, Tyler Durden says "the things you own end up owning you" which is likely a riff inspired by Buddhist or stoic philosophy. What do you think of this phrase? And given your current lifestyle, can you think of a different quote you'd offer in response?

The book is also fantastic, a must read for me. Although I love it, I have still never been in a fight. I love the message of the movie- relationships, not stuff, matter, and message runs community.

I don't have much right now. 3 shirts, a pair of pants and shorts. Some odds and ends. I do some pretty interesting and amazing things everyday, and not once in the last month did I really want anything more.

It has turned by life from stuff centric to relationship centric.

To get down to 15 items must have taken serious thought. Can you describe the process you used? Did you do it all at once, or one or two items at a time?

The 15 items was a simple goal. I was trying to tell my friends that my life would fit into a backpack. It wasn't until I turned my life into a number before the trip was official. I started with my clothing basics. 2 shirts, 1 pant, 1 short, 1 sandals, 1 sunglasses and underwear. I added a few 'must haves' for me like an iPad and camera. I added a backpack, toiletries kit, towel, and a few random things (pen, connector cable, chargers) and tried it out. After five weeks of the trip, there is more that I have not used in the bag than there is in the bag.

Given how few items you possess, has it changed how you look at your friends, family or other people you meet on your travels?

The weirdest thing is I don't have a home to go back to (homeless, you could say). I see a guy who owns a bag like me and spends his days begging or with nothing to do. I choose to have a bag and travel around while there are many I have talked to that do not choose to live on the streets. The guy is surviving, and it is really sad to think we are both equal except I have more in relationships and bank accounts. That is hard to see.

It is pretty funny to see peoples faces when I show them by bag and tell them it is everything I own. People either get happy or confused. The happy ones challenge themselves to think if they could do it (with wonder) and the confused tend to tell me that I shouldn't travel to 'dangerous' countries like Columbia.

One of my favorite interactions was at JFK. I talk to a lot more people now that I don't have a job, it is just interesting to see what people are up to, where they are going, what they are living for. A middle aged guy said I was elitist for traveling. I was standing there with everything I owned on my shoulders, being called elitist.

October 19, 2010

Poll: Write more or write better?

A question on my mind regarding this blog, is this: should I be writing more often? Or writing less, but writing better (however you choose to define it) things?

I want your vote: please take a second? Two clicks will do it. thanks.

View Poll

New Myths Webcast: Now on youtube

Thanks to O'Reilly Media, last week's webcast on the new edition of Myths of Innovation is now available free online.

Bonus links:

There's also an extended Q&A writeup (questions I didn't have time to answer during the webcast).

Free sample chapters here (PDF)

Buy the book on amazon.com (or read the 50+ reviews)

Clients who ignore you: how to handle?

In a series of posts, called readers choice, I write on whatever topics people submit and vote for. If you dig this idea, let me know in the comments, and submit your ideas and votes.

This week's reader's choice post: Handling clients who ignore your process.

How do you think that a client should be managed if they just do not want to understand the process or how things are being build? How should you react if a client always asks to shorten timings and they do not trust the people that are setting up the schedule just because they are not aware of the production process and are not willing to learn and understand?

There are only three answers.

Your process sucks. Maybe they have good reasons for ignoring your process. It's possible they see its flaws or it's too complex for what they need. This might not be true, but it's your job to consider the possibility they're right. One trick is to anticipate the likely points of tension during a project before it starts, and discuss them with your client before they happen. Then when they occur, you've preloaded their expectations for how to handle.

You need to stand firm and, with patience and empathy, explain it better. You might be right, but if they don't understand why, it doesn't matter. You can't expect people to pay extra money for what they don't understand. The skills of teaching and persuasion are unlikely to come with whatever domain expertise you have, so go work on those. Or find another consultant who is better and involve them (watch and learn). The last option is to share the tradeoffs and let them decide: "yes, we can get it done tomorrow but we'll have to cut one of these three features" or "yes, we can get it all done tomorrow, but the quality of each feature will drop".

Find new clients. There are some clients not worth having. If you find one, your goal is not to do business with them again. If they refuse to respect your expertise and don't trust you, a good working relationship is impossible (If your boss doesn't understand this situation, as in never willing to get involved and help, start looking for a new job). The occasional big fish who is difficult is hard to avoid, but generally there's little reason for a good firm that does good work to endure insane clients.

Is the web making us stupid?

The University of Washington launched a new TV show, Mediaspace, and the producers asked me to do a 2 minute commentary for each episode. This is from episode 1, where they interviewed Ben Huh, founder of I can has Cheezburger. The show is broadcast live, with realtime twitter conversation, and rebroadcast on UWTV.

The idea was to have an Andy Rooney type closing segment to finish each episode.

Monologue on the web making us stupid:

One of the silliest notions we have about media and change is that each new thing is either wonderfully good or horribly bad. The web itself, in the opinions of pundits, will either radically improve the world (Clay Shirky), or destroy our minds (Nicholas Carr). If you pay attention long enough, you see everything gets cast into these polarized, and while entertaining, mostly useless frameworks. They're fun, they spur debate, but rarely do they progress the conversation.

The truth is, all things have some good and some bad and them, and that goodness and badness varies depending on who you are. It's common sense to take this view, but since it's a not fun view, it's a way of thinking we often ignore. This way of thinking requires patience to sort out who is helped by something new, and in what situations. I can has Cheezburger might be silly, and you might not find it funny (I don't), but why is the fact that millions of people find something funny, that I don't, a problem? I'd rather they find something funny and laugh a little more, than find things that enrage them, and make them hate a little more.

Lowbrow humor has always had a place in high-brow culture, and to assume some people who like lol-cats can't also like Monty Python or Tchaikovsky reflects a limited imagination of the wide range of tastes most people have. The notions of a guilty pleasure reflects our puritan roots more than the nature of the pleasures themselves.

Most important of all perhaps is the recognition that what's most popular is rarely the best. This has always been true from books, to newspapers, to radio, tv, and the web– there is a lowest common denominator required for mass popularity and once you recognize the difference between the popular and the good, the existence of amazingly popular blogs about silly things seems fairly ordinary in the history of American media.

A better question perhaps is how can we use the lol-cats and the chat-roulettes of the world, these super easy forms of content creation, as a cultural Trojan horse of sorts. Showing the young they can be makers, but not just of the trivial. Once you learn to make something, anything, the possibility exists the next thing you make will have more meaning than the last. And that's what I'm hoping our technologies do for us: help us to create meaning. But where are the tools for making real works of art, or expressing thoughts and ideas with deeper and longer effects than just a few moments of laughter? That's what I'm still looking for. If you're looking too, let me know.

You can watch the entire first show here. Or just my segment, below:

October 18, 2010

Ray Ozzie, Microsoft and change

I'd occasionally get asked what I thought of Ray Ozzie at Microsoft. I'd say this "Great guy, a worthy legend, but he'll have little effect". Why? They'd ask.

And I'd say: "because he's not a VP for an actual product."

You can't lead in the abstract. You have to get skin in the game. Today MSFT announced he's leaving and I'm not surprised.

In the past I've criticized on idea of job titles like VP of Innovation or Chief Innovation officer. Chief Software Architect, Ozzie's title, had similiar problems. It means little to those with real power inside a company. Makers of things, like developers, give the most respect to people who ship things. What does a VP of Innovation ship? What does a Chief Software Architect ship? Nothing. Slide decks and vision plans don't compile. You can prototype and speculate all you want, but that's at best indirect influence on what the rest of a company is doing. You can't be a leader from the sideline. Give advice? sure. Make demos? Absolutely. But if a real risk needs to be taken you are not the person with the power to take it.

We'd have to ask people across MSFT if Ozzie had an impact on them. As an outsider, I can't say with any certainty if he did or he didn't.

But I know for progress to happen you must get in the middle (or be the leader of the thing that is in the middle). I don't know if Ozzie was offered ownership of a product or division and said no, or if that was never in the cards from Ballmer. Either way, the fate was set early on as it is whenever a high profile outsider does a tour at a company (Bill Buxton, and others at Microsoft Research, come to mind). You can earn your salary and have value, absolutely, but if you are not a key person on a key project, less can be expected of your net impact on a company as a whole.

For the industry I'm happy to see Ozzie leave – I'd have been happier to see him as CEO, or VP of a product, at MSFT, that would have been fascinating to watch – but since he's leaving my bet is he will take full charge of some new thing and that will be the best for all concerned. I look forward to what comes next Mr. Ozzie.

The fallacy of "They Don't Get It"

A phrase uttered by the frustrated is "They don't get it". When spoken among colleagues a chorus of heads will likely nod in affirmation. And while conferring over beers or lattes, someone will respond "Yes, what is wrong with them?" while everyone's mind spins on thoughts of how obvious it is, and how stupid they must be.

From political movements, to particular professions, they don't get it is a pseudo-rallying cry of the ignored and the powerless. But it serves only to bond people in their despair, instead of rallying them towards progress. To say "They don't get it" is giving up. It spreads assumptions about the nature of ideas out into the world, pretending there is no alternative, despite history to the contrary. Dangerous phrases like this demand disarming.

There are four traps lurking inside that are easy to disarm with questions:

Who are they? If there is more than one of them, they are in fact different people. Some of them will get it better than others. They might all be fools, but one will be least foolish, and that person is where progress begins. There is always one person most open to discussion and progress begins with them. Lumping a group together into a Borg-like entity called "They" is a convenience that keeps you stuck in the same place. It protects you from having to take the personal risks required for progress to happen, and progress requires risks.

What is it? Similarly, any idea is comprised of smaller ideas. If you lump them together with one name, as in "They don't get Design" or "They don't get the First Amendment", you're pretending Design or the First Amendment is an all or nothing proposition, which ideas never are. Until you break a large idea down into small bite-sized pieces, you can't see which parts are understood, misconstrued, or ignored. Until that moment, you don't understand the problem well enough to try and solve it. You really don't know what the it you're so angry about is.

Us and them. Socrates feared people who were certain about their own knowledge. He saw them as the least-wise people there are, as certainty creates a closed mind, blind to new knowledge or change of any kind. It's possible that they see you in the same exact way you see them. They wonder why you don't get their it. If nothing else, you and them share this view of each other. This is great news – you now have something in common! Their militancy in their thinking might mean you are more like them than you realize, an observation which should motivate you to rethink your attitude.

You might be wrong (or are right, but not in the way you thought). The high school social studies exercise of arguing both points of view on an issue is one shamefully lost in the adult world. Even Jesus Christ would say you should have compassion for your enemies, in part, I think, because empathy for their position will help you see your own more clearly, and the resulting clarity increases the possibility of the resolution you claim to seek. You still might not agree, but if you understand them, the way you try to engage with them will change, and for the better.

The fallacy of "They Don't Get it"

A phrase uttered by the frustrated is "They don't get it". When spoken among colleagues a chorus of heads will likely nod in affirmation. And while conferring over beers or lattes, someone will respond "Yes, what is wrong with them?" while everyone's mind spins on thoughts of how obvious it is, and how stupid they must be.

From political movements, to particular professions, they don't get it is a pseudo-rallying cry of the ignored and the powerless. But it serves only to bond people in their despair, instead of rallying them towards progress. To say "They don't get it" is giving up. It spreads assumptions about the nature of ideas out into the world, pretending there is no alternative, despite history to the contrary. Dangerous phrases like this demand disarming.

There are four traps lurking inside that are easy to disarm with questions:

Who are they? If there is more than one of them, they are in fact different people. Some of them will get it better than others. They might all be fools, but one will be least foolish, and that person is where progress begins. There is always one person most open to discussion and progress begins with them. Lumping a group together into a Borg-like entity called "They" is a convenience that keeps you stuck in the same place. It protects you from having to take the personal risks required for progress to happen, and progress requires risks.

What is it? Similarly, any idea is comprised of smaller ideas. If you lump them together with one name, as in "They don't get Design" or "They don't get the First Amendment", you're pretending Design or the First Amendment is an all or nothing proposition, which ideas never are. Until you break a large idea down into small bite-sized pieces, you can't see which parts are understood, misconstrued, or ignored. Until that moment, you don't understand the problem well enough to try and solve it. You really don't know what the it you're so angry about is.

Us and them. Socrates feared people who were certain about their own knowledge. He saw them as the least-wise people there are, as certainty creates a closed mind, blind to new knowledge or change of any kind. It's possible that they see you in the same exact way you see them. They wonder why you don't get their it. If nothing else, you and them share this view of each other. This is great news – you now have something in common! Their militancy in their thinking might mean you are more like them than you realize, an observation which should motivate you to rethink your attitude.

You might be wrong (or are right, but not in the way you thought). The high school social studies exercise of arguing both points of view on an issue is one shamefully lost in the adult world. Even Jesus Christ would say you should have compassion for your enemies, in part, I think, because empathy for their position will help you see your own more clearly, and the resulting clarity increases the possibility of the resolution you claim to seek. You still might not agree, but if you understand them, the way you try to engage with them will change, and for the better.

October 15, 2010

(Seattle) This Sunday – at Ada's Books 4-6pm

I'll be at the lovely new bookstore, Ada's, on Capital Hill, from 4-6pm. They have Myths for sale, as well as a selection of my favorite sci-fi & science books, but happy to chat with anyone about anything. So come on down. Possibility of going our for some beers afterward.

Ada's Technical Books

713 Broadway East

Seattle, WA 98102

Contact: 206-322-1058, contact@seattletechnicalbooks.com

Q&A from Myths webcast

Here's the Q&A from my Myths day podcast about the new edition of The Myths of Innovation.

Apologies for the delay in getting this posted. You see, Bono asked me to call Jon Stewart to let him know Oprah misses him (this is a bad inside joke in reference to a bad joke I made during the webcast).

Here's all the questions posted in the chat room – with my answers. Other questions welcome – leave in comments:

Naomi Maloney: Q. Aren't we really talking about IDEAS?

Sure. But that's just more vocabulary. What is an idea? When you're dead, is an idea you had in your mind more important than an idea manifested somehow in the world?

You can spend weeks debating which vocabulary is best for thinking about creativity – it is fun to a point. But then you realize you haven't done any real work towards solving any real problem. I'm happy to yield to other people's vocabulary if it gets everyone to actually make or design a prototype for something sooner. Most people have an idea for a book / movie / company / product / thing, but never manifest in the world in any way. The hard part is rarely the idea. Or what vocabulary they're using. The problem is asses in chairs, or at whiteboards, or in code, or in a lab, actually making something.

Venus Picart : I heard during an MIT conference that innovation is not innovative unless it finds a market. But nowadays, that is heavily dependent on funding, aka VC's. the purse strings are controlled by not so innovative people. Can you comment briefly on that?

Finding a market is a fickle thing. Most major innovations were around for awhile, but it took years to find a market. Fax machines, copying machines, cell phones, digital music players – the list is long. Despite what people at conferences say, you can not predict nor control markets. To be an entrepreneur means you are willing to take risks, in hopes that if things pan out you will benefit from them. But even with a great idea, and a great product, and great timing, most new ideas and companies fail. At least at first.

That said, there is always room for the self-funded entrepreneur. You can find them in film, in books, in every industry. They make up for their lack of resources with cunning, daring and unencumbered brilliance (No committees, no approval requests, no gates). 37 signals is as well known for not taking VC funding, as they are for their products. The web does democratize information – PR has changed. The barriers to entry are lower than ever in history for many kinds of ideas.

You might have to make your idea smaller, or pick a different market, but there is and will always be ways to be successful funding your own ideas. Taking VC or investment gives away the most precious thing you have: your own control over your own ideas. What good is a $20 million budget if you can't use it in the way that best serves your vision? You'd be better off with $500 and downsize to a studio apartment, if you can keep your independence of thought.

David Cox: Have you read Bruce Sterling's Shaping Things? What did you think of what it was arguing for?

Nope. But I hung out with him in a bar once. He's a very smart and entertaining guy.

Ray Luong: do you see video game design as a vanguard to learning about innovation? a lot of game teams seem to exhibit many of those traits you talked about today.

The problem with major video games is they are obsessed with the movie industry. They have modeled many of the processes and strategies after movies (e.g. game studios => movie studios). They aim so much of their effort at trying to be like film, which results often in beautiful games that are awful experiences to play. They also suffer from aiming at 15-21 year old men, or people who like to escape into realities designed for 15-21 year old men, and that's limiting in various ways.

Games like Braid, Limbo, Portal, or Shadows of the Colossus, that take big risks on gameplay are definitely good stories for how to develop different ideas. But they're mostly from the independents – not from the majors, who mostly make the same kinds of first person shooters and roll-playing games they have for years.

Scott Clamp: Q: Do innovative people have a more diverse social network (cross-pollination of ideas) or do they have a loner mentality?

Many breakthroughs occur when someone takes an idea from one domain or industry, an idea that is well accepted there, and brings it into a different domain that is new to the same idea. The more diverse your social network, or the kinds of books you read or conferences you go to, the more opportunity you have to find ideas of this nature. The number of famous loners is small – even Newton, who was as reclusive as they come, studied in university for years and had colleagues and supporters who helped him develop his work – certainly in his early years.

Tim Ake: Q: I just purchased the book, but it says that it is v.1 – will we get the updated version?

Hmmm. The paperback edition says First printing: August 2010, and the cover has black and red text on grey. Not sure where any of my books say v1. If you managed to buy a copy of the 2007 edition, sorry but there's not much I can do for you.

Eric Wayte: Q: What's your take on Oracle's strategy of innovation through acquisition?

Most successful companies, certainly tech companies, use their financial advantage by acquiring other companies. It rarely works in a way that benefits consumers – but it does benefit companies, sometimes. If nothing else, taking a potential competitor off the market means they won't hurt you, and won't ever be available for your competitor to buy. Sometimes acquisitions are purely about talent – they want the people, not the product (although this almost never works out as the people leave once they max out on their signing bonus).

In short, few acquisitions work out. There are too many variables and culture changes required (Microsoft did actually have a few good ones: PowerPoint, Frontpage, Hotmail). But most don't work out well. But strategy wise, if you have a big resource advantage, it's a move your enemies can't match: it can intimidate competitors, draw media attention, and make people look more carefully at what else you're doing.

Eva Springer: Q: Why don't you talk about play?

I only had about 40 minutes! Hard to talk about everything you know.

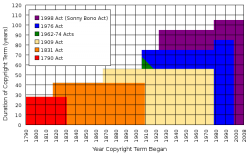

John Walker: Q: How do copyright laws complicate your notion that new ideas are combinations of old ideas?

The history of copyright makes clear that the intention was to protect intellectual property for a limited time - to reward them for their efforts, but to eventually release copyrights into the public domain. The problem isn't the idea of copyright – but the changes we've made to make it close to permanent (see chart):

It's clear many kinds of ideas are not patentable. I have my name on a handful of software patents, and I can tell you these are far from the best ideas I developed, or worked on. For example, the idea of a browser, or a web page, or web page layouts, or a thousand kinds of things are not patentable and can be reused in dozens of ways.

Anita Kuno: Q: When you are in a situation when the team doesn't trust each other, what percentage of teams listen to your advice?

Hard to know. Trust is tough. Relationships are tough. Half or more of marriages in the U.S. end in divorce. People dealing with other people is never easy. I feel that making people aware their real problem is trust, or communication, instead of obsessing about which management methodology they're using, at least gets them looking in the right place for the causes of their misery. Fundamentally if you work with people you don't trust, and can't fix it, you should leave. You'll never be happy or do good work with people you do not fundamentally trust.

Michael Gaigg: Q: Scott, many great ideas are based on existing ones – Do I or how much do one need to credit the base product/idea?

Depends. It's very easy to credit in most mediums. Books and webpages have links. Films have credits. Albums have liner notes (well, back when there were albums). Always credit generously. Most people find it an honor to have anything they're made mentioned at all. Simply say "inspired by Fred, Sally and Joe" if you don't feel comfortable being too specific.

Jason Shaf: Q Scott, Do you follow anybody on Twitter?

Ummm – have you used twitter? You can see who I, or anyone follows, by looking at their account – here's my list.

Benetou Fabien: Q: Do you think Steve G. Blank's book the 4 steps to epiphany is an efficient way to innovate?

Haven't read his book, however I have had people recommend it to me. I can only say I utterly hate the title. Taken without knowledge of the contents of the book, which might be great, the title expresses an attitude in complete opposition to what the history of invention and entrepreneurship supports, and what I teach.

Q: I loved the webcast and these questions are awesome, what should I do to get more?

Well, there's this thing called a book, and another thing called amazon. Together it means clicking here gets you 200+ pages of way better stories, thoughts, answers and more. And free sample chapters for the book are here (PDF).