Scott Berkun's Blog, page 38

June 28, 2013

How to build a culture of healthy debate?

From Monday’s pile of questions reader Ev Larsen asked:

Assumptions have an unnerving way of becoming facts and received wisdom over time. How do you build some functional assumption-checking into a project team, a process that generates useful feedback and moves the team effort forward?

The only real answer to questions of culture is you hire for it. Culture change is slow, much slower than technological change. This mystifies technocrats, as it should. People are much more challenging and powerful than machines will ever be.

Want more creative teams? Hire creative people. Want more risk taking? Hire for it. No single act defines an organization’s culture more than the people who are hired. If you want to shift a culture the most effective way to do it is to change who you hire.

The reason is simple: people are stubborn. By the time we’re 25 most of our personality traits, desires and habits are well defined and unlikely to change (it’s certainly possible but odds are against it). The primary point of leverage then is who a manager hires (and fires) and why. It’s far easier to hire for traits you need than to try to transform a person who doesn’t have them into someone that does.Even if transformation is the goal, we are social creatures and learn best from the examples around us. The more people in an organization that successfully demonstrate a trait, the easier it is for others to emulate and adopt it.

One great weakness of managers is their arrogant faith in the omnipotence of management. There is the belief, reinforced by management consultants and business books, that simply by decreeing “be innovative” or “work smarter” magic forces that transcend the limits of sociology will transform conservative or stupid people into being otherwise on your behalf. The ability of a manager to achieve something depends heavily on whether the people on staff are even capable of doing that thing. You couldn’t convert the local bakery into a nuclear physics research lab simply by changing the manager or the management philosophy, but that doesn’t stop executives from trying. The current trend of organizations built for decades around core values of conservatism and rule-following magically transforming into entrepreneurial risk taking powerhouses simply because the CEO tells them to is a classic example of this hubris.

My broad ranting aside, to answer the specific question some people are instinctively better at challenging assumptions than others. They ask more questions, have more doubts, and are willing to act on them. I don’t know why they are this way, but I know these people exist. If you want more assumption checking, hire for it. These people are harder to manage since they naturally challenge authority, but if you want assumptions challenged that includes the assumption of hierarchy. Diversity is a natural way to bring more questions into an organization as people with different experiences naturally question each other when they get together to build something. Age difference is one of the most useful kinds of diversity as new graduates and old veterans have many different assumptions, and if healthy debate is encouraged the results will be the best synthesis of those perspectives.

The second part is how you as the manager respond to having your assumptions challenged. If you continually demonstrate that you, the person in charge, is comfortable being challenged, or yielding your idea to a superior one suggested by a colleague or subordinate, everyone who works for you will emulate that behavior. Alternatively if you dismiss challenges, or yell at people who challenge you, the culture of fear your behavior creates will dominate no matter who you hire or how great you proclaim it is to challenge assumptions.

The platitude “there are no sacred cows” is very easy to say, but I’ve rarely heard it said by someone who didn’t really mean “only my sacred cows are sacred.” It takes great confidence as a leader to keep an open mind as the size of their empire grows.

The third part is behaving in ways that separate people from their ideas. Healthy debate is easy if no one is taking the results personally. Most heated debates involve people who have trouble separating their opinions from their identity (the lack of ability to find any humor in a debate is a good sign that someone is taking the issue too seriously). If I draw what turns out to be a lame idea on a whiteboard, in a healthy culture it’s reinforced that the idea is lame, but I’m not. I can still be smart and valuable. Perhaps my lame idea will help lead to a great one. This trust in coworkers is what allows ideas to be debated, attacked, torn down, twisted, reused and improved without any fear of offending anyone. Most successful creative cultures in history were based on this separation. It’s another set of behaviors that leaders must demonstrate regularly. Many talented organizations produce little of merit because of how sensitive people are of criticism, and the fear of offending people or being offended trumps everything else.

There are definitely techniques that encourage the challenge of assumptions but they only work if the above factors are true. My favorites include:

Postmortem / Debrief: after every project a long conversation should take place where people review what happened, what assumptions were made, what went well and what could have gone better. If lead properly (and witch-hunts and finger pointing are avoided) these conversations are gold. They inject introspection and self-awareness into the culture.

Experimental attitude: The basic notion of an experiment is you have a hypothesis (which is really a set of assumptions) and you find a way to test it to see if it’s right. Most experiments fail, but the attitude is it’s the only way to learn. Leaders should always be running experiments of some kind with their teams. “Lets try working this way for a week and see what happens.” The continual exposure to the cycle of “assumption, test, learn, repeat” diminishes fear around asking questions and raises everyone’s comfort with making, challenging and testing assumptions.

Discuss books about thinking: many books address problem solving, question asking, and challenging assumptions, and if read as a team provides a meta-example for exercising what the books try to teach (“e.g. what assumptions in this book about questioning assumptions should we question?) Although it’s more about problem solving, Are Your Lights On? is one my favorites for inspiring people to think more critically, and humorously, about everything.

What do you think? Are there other methods to encourage a culture of questioning assumptions?

June 27, 2013

When to quit working for a bully?

From Monday’s question pile an anonymous reader asked:

After five years of consulting I accepted a full time job with a startup. My hiring manager is someone with whom I’ve worked as a consultant: I knew he had a temper, which is why I declined his first few invitations to work for him. After a full-court press (by him, his CTO, and the founder) I signed on.

The salary is amazing, the work is interesting. And he promised to control his temper. It’s been two months and he had his second nuclear meltdown all over me last week – a total ambush. He’s an out-of-control bully behind closed doors, and rules by fear and intimidation. He’s lost friends and employees as a result of this character trait.

The job I signed on for isn’t the job I’m doing. The players have changed; a new clique-team of developers have been put in charge. They are disinclined to work with folks they didn’t hire. They’re jockeying for control conducting political power plays, micromanaging me (and I’m a Director), and trying to slice my position into being marginally useful instead of being integral to the team and product.

What to do in this situation? I’m really at a loss on how to improve the situation, aside from walking away.

Walk away, walk away, walk away. Run if you can. Crawl if you must. But leave.

Damage to your health, mental or otherwise, is something no salary or perk can compensate you for. Ever.

If you were starving or were unable to afford new shoes for your kids I’d understand working in a hostile workplace, but otherwise it’s a sign of lack of self-respect. The existence of someone with his problems in a managerial role means his boss has problems too. It always runs deeper than just one bad seed: it takes at least one other bad seed to overlook the need to fire the first bad seed.

It is never your job to fix another person’s psychological problems. If a job requires this for you to succeed you are set up to fail. You should have never believed in his commitment to change as most people don’t possess the ability to make those changes, certainly not as quickly as he promised. Your years of working with him told you more about what to expect than anything he could ever say.

Startups are chaotic places. It’s not surprising that things have changed. But every major change is an invitation to you to change your employer. Take that invitation as a gift. Get out now, on your terms, with your sanity and self-respect intact.

Also see: How to Survive a Bad Manager

Should you self publish your first book?

From Monday’s question pile reader Gutenberg Neto, who has one of the best names ever for questions about publishing, asked:

After releasing books both with a publisher and also independently, do you feel like one of the approaches is overall better than the other one? These days, with so many distribution platforms available, it’s easier than ever for anyone to self-release a book.

But for a first-time author do you think that it’s still valid to look for a publisher, or releasing independently is the best option even if the writer has no previous experience and audience to leverage initial sales? Thanks!

My experience self-publishing Mindfire: Big Ideas for Curious Minds was excellent and I wrote about the details here.

I don’t have a single answer. It depends on the author and the book.

Publishing a book no matter how you do it is best thought of as a entrepreneurial experience. You have an idea for a product, in this case a book – how much of the work of making and selling the product are you comfortable doing on your own?

From this view a publisher is a business partner. They provide funding, expertise, co-ordination and guidance. They have in-house editors, designers and proofreaders who will help you. For those things you will pay them a fair share of the possible income the book generates. This is a good deal if you don’t want to find those experts on your own, or have no interest in co-ordinating the entire project yourself.

If you can find a good publisher to work with, and plan to write many books, it is absolutely valuable to work with a publisher at least once. You will learn from experts and have a safe framework to learn from, a framework you can choose to ignore if you self-publish in the future.

On other hand, if you’re someone that’s a natural self starter, loves to learn, and are good at finding and leading talented people who have expertise you don’t, self-publishing makes sense. You’ll have more control over the book and get more of the rewards. But you’ll also have significantly more work to do.

Common mistakes authors make when working with publishers:

Assuming you are a rock star. It’s exciting to have a publisher make you an offer, but remember, to them you book will never be as important to them as it is to you. To them your book is #56 of 120 they will put out this year, wheras to you it might be the only book you will ever write. Publishers rightfully prioritize among all of their books each month to decide which will get more of their marketing and PR attention.

Believing the publisher will do all the marketing for you. Many authors assume the burden of marketing is on the publisher but that has never been true (unless you are Stephen King or J.K. Rowlings). The author is always at the center of marketing and PR for books. It will be up to you to find speaking engagements, to be available for interviews, and to use your networks and connections to promote the book. Good publishers assist you, but the burden is always on the author. If your book is deemed more important than others you will get more support, but the burden is still on you.

A published book won’t magically get you a following. Earning an audience takes time and effort. The book itself only helps grow your reputation if people find out about it and read it, which requires marketing. A book helps grow a following since it gives something to talk about and share, but a book doesn’t do the marketing work itself.

Dismissing your editor. I’d rather have a great editor at a mediocre publisher, than a mediocre editor at a great publisher. Editors lead the project that is your book. They attend meetings you can’t and and fight on your behalf for resources inside the publisher. Good editors give you tough love, feedback you need to hear that improves the book. Mediocre editors don’t do much at all. Of course your book might be a low priority project on the desk of a great editor, which is why the editor’s interest in your project is critical too.

Common mistakes with self-publishing:

Authors are naturally arrogant and assume they know everything. When self-publishing it’s easy to assume you are right about everything since there is no one arguing with you, even when you’re dead wrong. There is deep expertise in the tasks of choosing the theme, title, outline, cover, and style of a book. At a publisher there would be a specialist in each of these roles working with you. If you fail to avail yourself of experts the quality of the book will suffer.

It’s easy to be cheap and it will show. From the cover design, to the interior, to the index, many authors don’t understand the impact of making the cheapest choices. It shows. Books are extremely competitive. It’s a hostile and unforgiving landscape. The details matter.

You must be your own marketer. At minimum publishers announce your book to the world through their mailing lists, websites and catalogs. If you self-publish you are entirely on your own. If you are serious about sales you need a marketing plan and a commitment to invest even more time marketing the book than you would if working with a publisher. Marketing is hard: it’s an entirely different kind of challenge than writing a book. And marketing a book starts long before the book releases.

It’s natural to write a book only you want to read. Few authors do market research or solicit feedback from smart colleagues to define the market for the book. Writing a book proposal, something required to work with a publisher, forces authors to think long and hard about what the book is and who will buy it. Simply because you want to write it doesn’t mean anyone will want to read it. Working with a publisher ensures dozens of questions are asked about who the book is for and that the answers make sense.

There are too many variables to give a single answer. If you can find an editor and publisher you’re happy with, and they believe in the specific book you want to write and how you want to write it, all other things equal I’d say go with a publisher for your first book. It will let you focus on writing a great book, and if the first book does well you’ll have more flexibility in what you do the second time.

More than anything, my advice is this: write the book and publish it. Don’t let this decision be the one that holds you back for year after year. If you can’t decide, self publish. No one can ever stop you from self publishing. And there is always the possibility you can release the book again with a publisher later (this happens often). The real challenge is the book itself and don’t let this decision stand in it’s way.

Book Review: Designing Together

I was honored to write the forward for Dan Brown’s new book, Designing Together, because I thought it was excellent. It’s the first book I’ve seen that solves a primary reason why designers fail: we stink at working with each other or other people. Brown’s book is the best, and possibly only, resource I’ve seen for saving design teams everywhere from themselves.

I was honored to write the forward for Dan Brown’s new book, Designing Together, because I thought it was excellent. It’s the first book I’ve seen that solves a primary reason why designers fail: we stink at working with each other or other people. Brown’s book is the best, and possibly only, resource I’ve seen for saving design teams everywhere from themselves.

Brown writes in the opening pages: Successful design projects require effective collaboration and healthy conflict.

Everyone agrees with this, yet almost no one experiences it. Why? And why is so little attention paid by designers and team leaders to this fundamental problem? There’s finally a book everyone can use as a stepping stone to solving this perennial and tragic problem in how creative teams work.

If you want to make great things, get excellent work and constructive feedback from your coworkers and finally achieve everything your talents make you capable of, that quest starts with Designing Together.

The forward itself serves as my review. Here it is:

The cliché of Forewords for books is they have a seemingly famous person express how wonderful the book you’re about to read is. But the secret we authors don’t want you to know is often the Foreword is written by a friend who either lost a bar bet or is trading for the destruction of unsavory photos in the author’s possession.This explains why most Forewords are dreadfully dull and unworthy of the book they’re in. I can promise you I’ve only met Dan once and owe him nothing.

I’m writing this Foreword simply because this book is exceptional. It captures the central flaw in the talents of most designers: how to create with other people. And it achieves this without falling victim to the clichés and platitudes that render most books of this kind useless.

Back when I was a student, my vision was a lifetime of making world- changing designs. But in these dreams I always had a starring role, with minions scurrying about, taking every order and doing all the work I didn’t (or couldn’t) do. How naive the dreams of young designers are. No great thing in the history of design and engineering was, or ever will be, made this way.

It always takes a team of craftsmen, working in harmony, to make something great. Working with others has always been ignored in design culture. And the result is that the student fantasy lives on far too long in the careers of creatives, squandering their talent and their happiness, too.

If you pick any great design from today, or in history, and dig into the details of how it was made, you’ll find a team of talented people working well together. Each contributing and building on each other’s work.They didn’t always like each other, but they learned how to put the quality of the results ahead of petty differences. Their ability to do this isn’t magic. Nor is it based on their creative talents. Instead it’s a set of simple attitudes and skills this book clearly explains. While I’ve learned many of these practices along my career, I’d never seen them as clearly named, explained, and taught as they are here.

If you want to escape work that buries you in stress, disrespect from coworkers, or meetings that resemble Custer’s Last Stand, you’ll find solutions in the following pages. I’m jealous of the moments of clarity awaiting you in the chapters ahead.

Go buy Designing Together now.

June 26, 2013

How to find your niche

From my Monday question pile Jennifer asked:

How do you find your niche?

This seems like a simple question but the more I thought about it the less I liked it. It’s a question filled with assumptions. Is there just one niche for every person? Can you make your own niche rather than find one? Is this even the right metaphor? Niches are places carved into stone for stone figures to spend all eternity. Unless you want to spend all of your waking hours in the same place until you die, a niche isn’t the best way to go.

But the word find is good because it’s a verb. Consider the question: How would you find your car keys? How does anyone find anything? The answer of course is you have to look. People who are better at finding are better at looking, or are willing to look in more places and do a more thorough job in each place they look. Or consider: How do you find what clothes to wear? You probably go to your closet and try different things on to see how they fit and look. The advantage of trying to f ind your place in life, as opposed to car keys, is that like clothes there isn’t just one possible thing to find. And to follow my mixed metaphors further, while you can’t make car keys or clothes, you can possibly make your own career, or blog, or lifestyle (Actually, unlike me, you might be able to make your own clothes too).

The easy conclusion then is people struggling to find something need to improve their looking skills. They need to do more experiments with their lives and more passionately invest in those experiments. Far too many people dream about a different situation but take little action, and the actions they do take are by half, with one foot always on the ground. They never realize it’s their lack of commitment that causes the emptiness that disappoints them. But of course there are no guarantees: it’s always possible you’re looking for something that doesn’t exist. The rub of being a seeker is the acceptance that not everything can be found.

Related things people wish to find include:

How do I find what to do with my life?

What should I do for a living?

Where should I live?

Who should I spend my time with?

All of these questions have the same solution: you try something, you pay attention to how you feel about it, and then you try something else until you are fulfilled enough that you’re not asking these questions all the time (or you reset your expectations).

In a post I wrote called How I Found My Passion I told my story of how I ended up as a writer. In that post I mentioned four piles to think about:

Things you like / love

Things you are good at

Things you can be paid to do

Things that are important

It’s rare that one activity qualifies for all four, but your niche is likely found in activities that qualify for more than one.

June 25, 2013

My process for blogging

From my Monday question pile, my friend Angela asked:

As an active blogger and communicator, I’m curious your setup. Obviously love your content, but I’m interested in your process. I assume you’re a one man show, so I also assume you’ve got your process locked down because you’re soooo smooth, man! :) xoxo

My answer is a ramble. I tried to write this in an easy to follow way but had to scrap it because it was a lie. It turns out an honest description of how I blog is not easy to follow. Moreso, for blogging alone I’m not convinced I’m a good example for emulation. I have good basic self-discipline for writing and that’s what explains my productivity more than anything else. Part of why I enjoy blogging are its many freedoms. I deliberately don’t approach it with the same procedural rigor other bloggers do.

For more useful advice: when I worked for WordPress.com I studied their data on which blogs were successful and studied how popular blogs worked. I wrote up two summaries of what I learned and that’s the advice I still point bloggers to: How To Get More Traffic and How To Get More Comments. It’s good, simple practical advice.

For any regular readers it’s clear I don’t have a strict process. I don’t publish on a schedule (although I’d get more traffic if I did) and I don’t post about specific topics on specific days. It’s chaotic and I don’t advise bloggers copy this, but it works for me so far.

If you forced me to shape it into a process it’d look like this:

Wake up – be glad I’m not dead

Write something (could be in my private journal, a draft blog post, part of a book…)

Work until I run out of steam, or it’s finished

When stuck, go to the gym (do something physical)

Write again later in the day

Do other life things

Sleep

I realize this list has dubious merit. My central habit that makes it all work is the discipline of writing. It’s an internal discipline that isn’t generated by following a list of rules or magic steps. I write something nearly every day simply because I want to be a writer and writers write. There is no other way. My income comes from book royalties and speaking fees so I don’t stress about blogging schedules and such in the way many pro bloggers do.

Schedules: Sometimes I finish a post in one go. Most often I get to rough draft quality but can’t go further. But in all cases I show up the next day and either start something new, or progress something old. If I’m working on a book most of my creative energy will go towards progressing that before I’d think to blog. But sometimes the pleasure of writing something quick and publishing it instantly is just what I need to break up the long cycles of working on a book.

Roughly I post something new once or twice a week. Some weeks I do more, other weeks it’s less. But on average it’s a post or two a week. I’m more interested in creation than curation, but I see the value of both. On the curative side I often write book reviews and have had phases of posts that are mostly links or reports from events or places I’ve visited.

Posting new posts in the morning (PST) and early in the week seem to generate the most traffic. Twitter is a huge asset and drives a large part of the traffic my posts receive. I still have thousands of RSS subscribers but we’ll see if that matters anymore once Google Reader is gone. I often use the schedule feature of WordPress to plan when a post will launch days in advance. The Publicize feature, which I worked on while at WordPress.com, ensures even scheduled posts will be seen by my twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn followers.

Drafts: I have a large number of drafts in WordPress: 400+ (and a total of ~1500 published posts). Some are just a one sentence thought, or a link I want to comment on. Others are half written and a few are mostly done. I believe it’s healthy to be inefficient with writing. It’s ok not to finish many of the things I start provided I finish many too. I like having an inventory of posts in various states of completion. It means I can pick and choose based on the mood I’m in on that day and how much energy I have. I don’t see high draft counts as a waste, it’s an asset. I’m free to experiment and try crazy things with no fear. It’s my scrapbook and all creators need safe places to experiment.

Topics: I avoid writing about trends. By avoiding trends and picking timeless themes I don’t have the pressure to post this hour or this day, or to worry about who else said what already. And I know that the time I spend writing will still likely be relevant in a year or a decade, which won’t be true if I’m writing about something only relevant to the world for a week. I suspect this generates less traffic per post in the short term compared to people who chase trends, but probably more traffic in the long term (scottberkun.com has a strong long tail of old posts that generate significant traffic). Sometimes I do pick a hot topic as the hook to write about a deeper issue, but even then I know I can reuse the same post a year later when a new, but equally relevant hook, comes along.

Audience: Many of you readers found me because of one of my books. I try to make at least 50% of my posts related to the topics from those books: creativity, management, speaking and philosophy. The other 50% follows what I’m passionate, angry or curious about. This balance is reflected in my 50 best posts of all time. The mix has worked and I plan to continue (please advise if you don’t like the mix). There’s short term value in specializing more, but I plan to write until I die and I see the long term value in earning reader trust for my ability to write and think well on anything. That’s my ambition as a writer: that people want to read me at least as much for their interest in the mind doing the writing as they are in the particular topic.

Ideas: I always carry a moleskine or notepad wherever I go and I write down interesting things I hear. It’s a primary habit for finding ideas: listening, looking, experiencing and capturing. Opinion are easy to find if you’re curious and paying attention. Sometimes I just start a draft post in WordPress instead of the moleskine. I don’t care about losing these moleskines and the ideas I wrote down, but the habit of listening and writing in them is critical.

As a supplement to my habits, some readers do email or tweet links to articles they know I’d be interested in, or want me to comment on. This helps and I’m grateful to be popular enough that people care to know what I think about something.

Writing: To see how I actually write, I made this timelapsed video of me writing a 1000 word post. It explains most of the important things discussions of writing process never express well as we learn more by watching things first hand than nearly any other way.

Was this ramble of a post useful? I hope so. If you have other questions about process, leave a comment.

June 24, 2013

Q&A Monday: ask me your questions

Here’s an experiment: what question do you want me to answer? Something you want advice on? A topic you always wanted my opinion on? Or perhaps a challenge?

Leave a comment and I’ll pick a question to answer every day this week, assuming the experiment works and you fine folks leave me some questions.

June 20, 2013

Changing your life is not a (mid-life) crisis

“Most men lead lives of quiet desperation and go to the grave with the song still in them.” – Thoreau

Whenever someone over the age of 25 suggests a profound change, one of their friends will say, mockingly “you’re having a mid-life crisis.” It’s the only response adults know to offer. We have no label for an adult who continues to grow, who works to better understand themselves, and who periodically chooses to re-align their life with their dreams. And most of us, as friends, don’t know how to respond when someone tries to step out of the box we’ve held them in, a box much like the one we hold ourselves in all the time.

To see a friend change is scary because it challenges the assumptions we have about ourselves. To watch a friend change careers, partners or cities forces us to question why we’re not doing the same, questions we spend most days trying not to ask. The instinctive response we have is parental: “stop being foolish, get over this phase, and get back in the (miserable) box.” Little is more trivializing than calling someone’s pursuit of fulfillment a phase. It presumes the status quo of the past is best, when inspection likely reveals status quo provides only an illusion of quality. Status quo is familiar and even when it’s filled with mediocrity or misery we naturally prefer it to the unknown, even if we know that unknown could yield a great life. Perhaps someone who changes their mind on life choices by the hour deserves mockery from friends, but they also deserve respect for expressing the universal notion that there’s a better way to go about living.

Making a tough choice is precisely when we need the most help from friends and family, but choice divides people. Many see us for who we are but only a fraction see us for who we can be. When I quit my career at 31 to try to become a writer, I heard “you’re having a mid-life crisis” and was hurt by it. I wasn’t in crisis. I’d calmly considered my life and my choices. I had a dream for my life and I wanted to put as much energy into it as I could, but I discovered there was no system to rely on like the system that’d led me through school and career. But few people bothered to inquire what I wanted from my life, how this choice might improve my odds, and what they could do to help. I sought support from books (which helped me plan how to quit), but most that promised plans were shallow. You can’t expect a map if your plan is to go off the map. My best comfort came the honest uncertainty described in Bronson’s What Should I Do With My Life? which described a candid landscape of all the possible outcomes of wanting to live a dream.

Most people I talked to presumed staying in the same career my entire life suited me, simply because that presumption allowed them to hide in their own unexamined life choices. “Why would you throw this away?” I heard, as if making a right turn in a car destroyed the car and the road. It was a surprise to discover where support for my choices came from as it wasn’t always from the friends and family I’d have guessed. When you share your deepest dream it’s surprising who understands and who is mystified, or even disappointed. Part of the adventure of a big change is resorting who your allies are, as you can’t predict who among those you know will be most connected with the person you’re becoming. And the biggest surprise of all is the new important friends you make along the way, happy consequences of a scary choice made with conviction.

Buying a Ferrari or having a desperate affair with the babysitter are cliches of trying to recapture youth, as they find their present devoid of meaning or joy. These acts are often done by people who have no idea what is really bothering them, and like scrambling in a closet for clothes when late for work, the cliches are the easiest and most impulsive things to try. They only understand later that the desire for the Ferrari or an affair were likely symptoms of a problem denied and not the problem or solution itself. If they’re lucky the resulting true crisis those decisions causes forces them to dig deeper into what’s missing from their lives and pursue change.

I imagine for myself a lifetime of changes initiated by me. I know I’m too curious, and life is too short, to follow the conventional footsteps that everyone is quick to defend despite how miserable they seem in the following. We use the phrase “life long learner” but it’s corny and shallow, suggesting people who quietly take courses or read books after college with as if life were a hobby. We need a term for life long growers, people who continue to examine and explore their own potentials and passions, making new and bigger bets as they change throughout life. With or without a label I’ve learned more through my so called mid-life crisis about myself, my friends and the possibilities of life, than I could any other way and I plan to make similar changes throughout my hopefully long and amazing life.

June 18, 2013

The Year Without Pants: early praise and reviews

It’s been an amazing journey writing a book about my year working for WordPress.com. Now in the last three months before release in September it’s great to see some early praise come in for The Year Without Pants: WordPress.com and the Future of Work.

“The Year Without Pants is one the most original and important books about what work is really like, and what it takes to do it well, that has ever been written.”

—Robert Sutton, professor, Stanford University, and author, New York Times bestsellers The No Asshole Rule and Good Boss, Bad Boss

“WordPress.com has discovered a better way to work, and The Year Without Pants allows the reader to learn from the organization’s fun and entertaining story.”

—Tony Hsieh, author, New York Times best seller Delivering Happiness, and CEO, Zappos.com, Inc.

“The underlying concept—an ‘expert’ putting himself on the line as an employee—is just fantastic. And then the book gets better from there! I wish I had the balls to do this.”

—Guy Kawasaki, author, APE: Author, Publisher, Entrepreneur, and former chief evangelist, Apple

“If you want to think differently about entrepreneurship, management, or life in general, read this book.”

—Tim Ferriss, author, New York Times best seller The 4-Hour Workweek

“With humor and heart, Scott has written a letter from the future about a new kind of workplace that wasn’t possible before the internet. His insights will make you laugh, think, and ask all the right questions about your own company’s culture.”

—Gina Trapani, founding editor, Lifehacker

“Some say the world of work is changing, but they’re wrong. The world has already changed! Read The Year Without Pants to catch up.”

—Chris Guillebeau, author, New York Times best seller The $100 Startup

“Most talk of the future of work is just speculation, but Berkun has actually worked there. The Year Without Pants is a brilliant, honest, and funny insider’s story of life at a great company.”

—Eric Ries, author, New York Times best seller The Lean Startup

“The Year Without Pants is a highly unusual business book, full of ideas and lessons for a business of any size, but a truly insightful and entertaining read as well. Scott Berkun’s willingness to take us behind the scenes of WordPress.com uncovers some of the tenets of a great company: transparency, team work, hard work, talent, and fun, to name a few. We hear about new ways of working and startups, but we rarely get to see up close the magic that can occur when we truly tend, day in and day out, to building something bigger than ourselves.”

—Charlene Li, author, Open Leadership, founder, Altimeter Group

“ Once you’ve seen how WordPress.com does things, you’ll find yourself asking why your company works the way it does.”

—Tom Standage, editor, The Economist

“Berkun smashes the stereotypes and teaches a course on happiness, team culture and innovation”

—Alla Gringaus, web technology fellow, Time, Inc.

“The future of work is distributed. Automattic wrote the script. Time for rest of us to read it.”

- Om Malik, founder, GigaOM

You’ll be surprised, shocked, delighted, thrilled and inspired by how WordPress.com gets work done. I was!

- Joe Belfiore, Corporate Vice President, Microsoft

You can Pre-Order The Year Without Pants now on amazon.com or join the mailing list to be notified when it’s on sale and get exclusive content.

How To Write a Second Draft

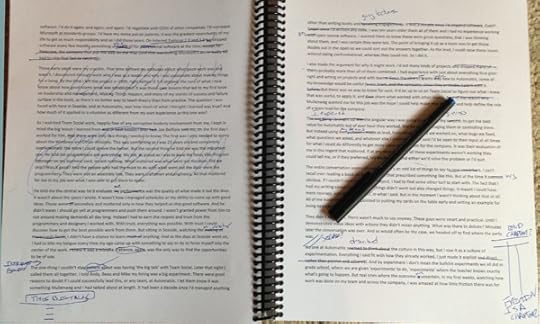

As I’ve been working on The Year Without Pants, I wrote recently about how to revise a first draft, including what I call The Big Read: where you sit down and read through the entire (first) draft in as few sittings as possible.

The result of that big read is a manuscript that looks something like this:

This set of pages had more notes than average, but every page has a fair share of commentary from me. I avoid rewriting as I read, focusing instead on giving myself as much advice and input for the actual rewrite, which happens later. There are many different kinds of suggested changes I note for myself:

Trivial typos, phrase changes, and line edits. If I catch something quickly I’ll suggest a change, but otherwise I’ll mark it with a question mark or circle.

Sentences or paragraphs that are redundant. If it reads redundant to me, it definitely will to a reader. I edit harshly. Having a complete first draft makes this easy, since I know no single paragraph matters as much to readers as it might to me.

Questions I need to answer to justify keeping a passage. As a reader I note things that don’t make sense, need better explanation, or sections with style problems such as unfunny jokes, distracting self-aggrandizement or even arguments that I myself question.

Notes on things repeated across chapters (probably should be killed). In a book length draft there is always unintended repitition where I make the same point twice or more without acknowledging it. This is bad. It’s like talking to someone with no short term memory.

Within chapter flow suggestions. Is the opening strong? the closing? Does each story and point flow? Can I reorder paragraphs to make it stronger?

Across book flow suggestions (should a chapter be earlier? later? killed?) – these are the scariest changes to consider. Moving large blocks of text around ripples through a book, forcing many other passages that need to be changed. This is why the big read is important: it’s the only way for me to keep most of the book in mind during the second draft. If I worked on a 2nd draft over several weeks, I’d have a harder time remembering where everything is and how it was written and have more fear of big changes.

Second drafts also incorporate feedback from other people. This is a challenge: everyone gives feedback differently and none match what I do for my own drafts. For the Year Without Pants I had feedback from 10 different people to consider:

5 co-workers from WordPress.com

4 old friends who are good at tearing drafts apart

My editor at Jossey-Bass

My solution was to compile the feedback into a single file I could skim through at any time during the 2nd draft process. I’d keep the manuscript open in one window, the notes from everyone else open in other windows and my hand edited print out of the first manuscript by my side. Then I could jump between them if needed to compare their thoughts.

The actual Rewriting is far easier than Draft writing

While it’s not easy, the actual writing of a second draft feels much easier than a first. My creative powers can be applied to improving, rather than inventing. I can never predict which chapters will give the most trouble, but there are always 2 or 3 that I do heavy work on, rewriting or reorganizing large portions. Most chapters are simply me following my own notes from the read, filling in the blanks and answering the questions I asked.

I always have the goal of making the book shorter as it goes through revisions. Even if I add new sections or revise old ones I want the majority of my actions to be ones of concision. The book should get tighter and tighter as I work, with my effort clarifying the writing, making the book easier to read.

When the 2nd draft is done, it gets handed to a copyeditor who helps polish up my grammar. Check out my post on What Copyeditors do, with examples from my books.