Scott Berkun's Blog, page 27

February 26, 2014

The Goal of My Life Explained (tattoo included)

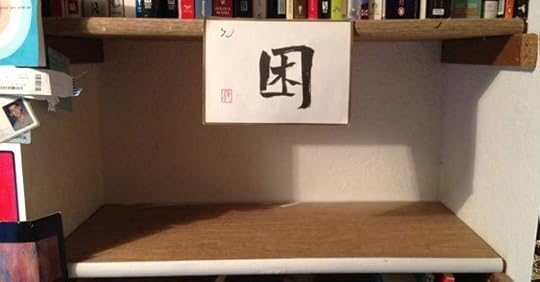

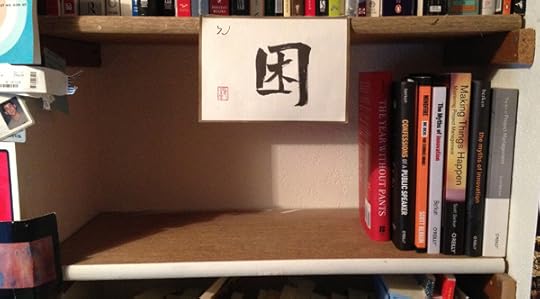

In my first book I put a simple photo on the author page at the end. It showed a shelf near my desk that I’d cleared. My goal, since 2003 is to fill this shelf with books I’ve written. This is an odd thing to do I realize but I want an interesting life, which requires doing odd things.

When I quit my career in 2003 to become a writer I needed a simple but powerful reminder about my goals. Books had changed my life many times and I was most interested in the challenge and reward of authorship. Since I saw the shelf many times a day (it’s to my right as I type this) I decided it was the perfect spot. And only filling it with finished books gave me a visual reminder to focus on.

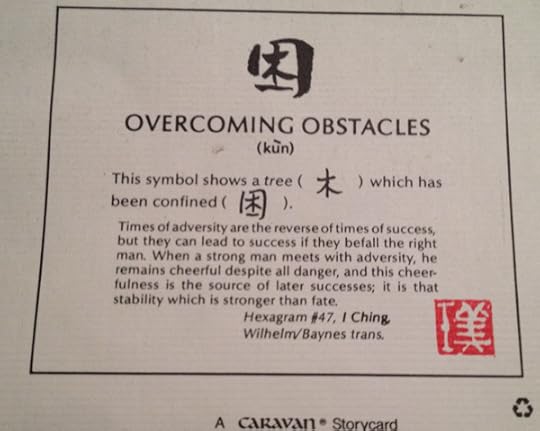

It’s cliche for Americans to swoon over Chinese symbols, and often they mean things very different from what we think (As my Chinese speaking friend Jeff likes to joke, “Uh, that symbol tattooed on your arm doesn’t mean Great Love, it means soup dumplings.”)

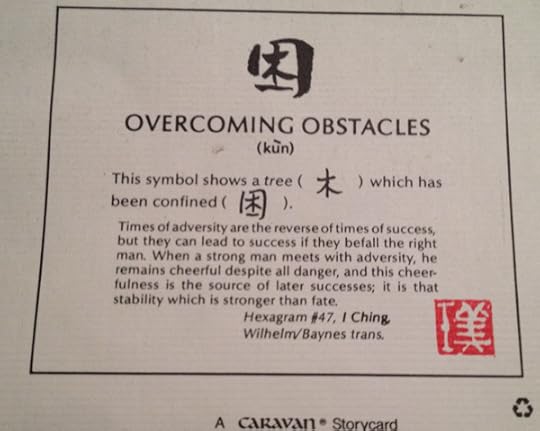

I found this card at Uwajamaya in Seattle around the time I quit. I liked what it claimed the symbol meant (see below). I love the quiet, steady strength of trees and it matched how I needed to be to reach my goal. I’ve learned in common Chinese the symbol/word means confinement more than overcoming, but I don’t care. The symbol has adorned my shelf for so long it means something specific to me regardless of its literal meaning.

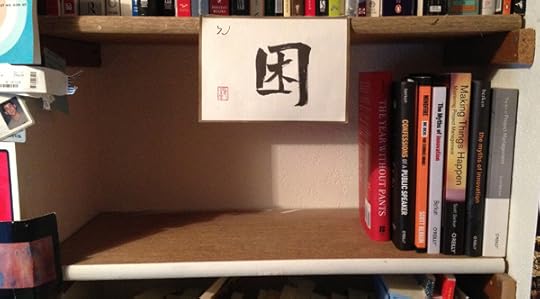

11 years later I’ve written 5 books and the shelf looks like this (see below). I have a long way to go. Translated editions don’t count, as that’d be cheating. I’ll need to write about 25 books to fill the shelf which will likely demand most of my life. That’s fine. I have nowhere else to go and no goal as meaningful as this one.

Although it’s a volume goal, I have no interest in writing bad books. I also have no interest in writing unnecessarily long ones. My popular essay collection Mindfire is comprised of revised essays from this blog, but I’d feel it was cheating if most of the shelf was recycled material. One book in five seems a fine pace for compilations and such.

Occasionally I am offered very nice conventional jobs where I’d have more security and income, but then I look at the shelf. Security and income are desirable things, but they have limited bearing on my ability to fill the shelf. So as tempted as I might be, I say no (The Year Without Pants was a notable exception). Writing and speaking are my only means of income.

Another reason I like this goal is writing books demands many things:

Polymathic thinking

Study

Curiosity

Passion

Connecting with friends and colleagues

Making new friends and relationships

Commitment to an idea

In the process of writing a book I’m forced to do many things in line with the kind of life that I want: An interesting one. As long as I focus on the shelf, many other good choices are forced naturally.

Most authors repeat themselves, writing the same kind of book repeatedly. The marketplace rewards familiarity and a writing life is hard enough as it is, so I understand why it’s common. Many of our most popular authors publish in narrow ranges. This is wise and lucrative, but ultimately limiting (the worst are creativity authors who exclusively write about creativity, which is not very creative). I’m taking the opposite approach for as long as I can. I’ve never written a sequel, because we all know how underwhelming sequels are. I have no shortage of ideas for books and I’ll keep moving forward until I’m forced to be more conservative, if that’s even possible.

I want to be a writer in the largest sense. I want to be an artist. I want to take big risks with my skills, which will help me discover exactly what abilities I have or don’t have and what good they can do in this world.

Last year I got my first and only tattoo. It serves as an additional reminder to me about why I’m here and what my goal is. I’m a writer which means I work with my hands. I wanted to keep the symbol with me, near my hands, all the time.

That’s my story. If you see me speak and notice the tattoo, now you know why it’s there and what it means.

Any encouragement is encouraged. Praise the crazy writer man! And thanks for supporting my work. Best wishes to you on your own goals.

The Goal of My Life Revealed (tattoo included)

In my first book I put a simple photo on the author page at the end. It showed a shelf near my desk that I’d cleared. My goal, since 2003 is to fill this shelf with books I’ve written. This is an odd thing to do I realize but I want an interesting life, which requires doing odd things.

When I quit my career in 2003 to become a writer I needed a simple but powerful reminder about my goals. Books had changed my life many times and I was most interested in the challenge and reward of authorship. Since I saw the shelf many times a day (it’s to my right as I type this) I decided it was the perfect spot. And only filling it with finished books gave me a visual reminder to focus on.

It’s cliche for Americans to swoon over Chinese symbols, and often they mean things very different from what we think (As my Chinese speaking friend Jeff likes to joke, “Uh, that symbol tattooed on your arm doesn’t mean Great Love, it means soup dumplings.”)

I found this card at Uwajamaya in Seattle around the time I quit. I liked what it claimed the symbol meant (see below). I love the quiet, steady strength of trees and it matched how I needed to be to reach my goal. I’ve learned in common Chinese the symbol/word means confinement more than overcoming, but I don’t care. The symbol has adorned my shelf for so long it means something specific to me regardless of its literal meaning.

11 years later I’ve written 5 books and the shelf looks like this (see below). I have a long way to go. Translated editions don’t count, as that’d be cheating. I’ll need to write about 25 books to fill the shelf which will likely demand most of my life. That’s fine. I have nowhere else to go and no goal as meaningful as this one.

Although it’s a volume goal, I have no interest in writing bad books. I also have no interest in writing unnecessarily long ones. My popular essay collection Mindfire is comprised of revised essays from this blog, but I’d feel it was cheating if most of the shelf was recycled material. One book in five seems a fine pace for compilations and such.

Occasionally I am offered very nice conventional jobs where I’d have more security and income, but then I look at the shelf. Security and income are desirable things, but they have limited bearing on my ability to fill the shelf. So as tempted as I might be, I say no (The Year Without Pants was a notable exception). Writing and speaking are my only means of income.

Another reason I like this goal is writing books demands many things:

Polymathic thinking

Study

Curiosity

Passion

Connecting with friends and colleagues

Making new friends and relationships

Commitment to an idea

In the process of writing a book I’m forced to do many things in line with the kind of life that I want: An interesting one. As long as I focus on the shelf, many other good choices are forced naturally.

Most authors repeat themselves, writing the same kind of book repeatedly. The marketplace rewards familiarity and a writing life is hard enough as it is, so I understand why it’s common. Many of our most popular authors publish in narrow ranges. This is wise and lucrative, but ultimately limiting (the worst are creativity authors who exclusively write about creativity, which is not very creative). I’m taking the opposite approach for as long as I can. I’ve never written a sequel, because we all know how underwhelming sequels are. I have no shortage of ideas for books and I’ll keep moving forward until I’m forced to be more conservative, if that’s even possible.

I want to be a writer in the largest sense. I want to be an artist. I want to take big risks with my skills, which will help me discover exactly what abilities I have or don’t have and what good they can do in this world.

Last year I got my first and only tattoo. It serves as an additional reminder to me about why I’m here and what my goal is. I’m a writer which means I work with my hands. I wanted to keep the symbol with me, near my hands, all the time.

That’s my story. If you see me speak and notice the tattoo, now you know why it’s there and what it means.

Any encouragement is encouraged. Praise the crazy writer man! And thanks for supporting my work. Best wishes to you on your own goals.

What If Managers Didn’t Get Paid More?

One of the many surprises from The Year Without Pants is that Automattic, makers of WordPress.com, doesn’t pay employees more when them become a team leader. They consider being a leader a role, not a job. One of the fun experiments this enabled for me while I worked there was to step down as lead and report to someone who used to report to me, something I’ve almost never seen happen gracefully before.

If managers don’t get paid more, this dramatically changes several dynamics about management and leadership:

Money is removed as the motivation for becoming a leader

Instead only people who purely want to be leaders take the role

If they’re unhappy in the role, they have no reason to stay

In many organizations getting promoted into management is the only promotion path. The result is many people ill suited and even uninterested in leading groups take on those roles, with negative consequences across the organization. If you know of managers who clearly don’t like managing, you and they have been victimized by an organization that has misplaced how and why it rewards people.

During my 20 months working at WordPress.com the people in lead roles were mostly stable, and many people had been in a leadership role for two years or more. But the clarity around leadership being a role changed how leads behaved. It made leaders far less territorial, for they knew, much like being a Senator or a representative, that they were part of a larger system. Leadership as a role was one of many cultural attributes at Automattic that are unusual for corporations, and it’s their culture that allowed them do to so many things we’d all love in our own workplaces.

February 24, 2014

FAQ about The Year Without Pants (with satisfying answers)

It’s been a great few months for my 5th book, The Year Without Pants. Thanks for spreading the word and helping it find its way. The book was named an , was covered by Forbes, Publisher’s Weekly, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, Fast Company, ZDNet, and hundreds more.

It’s been a great few months for my 5th book, The Year Without Pants. Thanks for spreading the word and helping it find its way. The book was named an , was covered by Forbes, Publisher’s Weekly, CNN, The Wall Street Journal, Fast Company, ZDNet, and hundreds more.

I toured Boston, NYC and SF last fall, giving dozens of lectures about the book. Here in a single post is a summary of the best and most commonly asked questions I’ve heard. Please leave a comment if you have a question you don’t see here and I’ll answer it.

Did WordPress.com know you were going to write a book when they hired you?

Yes. The book’s introduction explains this. Matt Mullenweg (WordPress founder) offered me a leadership role and I said I’d do it only if I could write about it. He agreed. My team knew about it early on, and much of the company knew about it before I left after working there 20 months. Since 2003 I’ve been primarily an author and I couldn’t imagine taking a conventional job unless I could frame it as research for a writing project. I was hired in August 2010 and left May 2012. The book released Sept 2013.

What were the biggest lessons you learned?

That this is a frustrating question! If I thought I could summarize 18 months of my life into bulleted list I wouldn’t have written the book. But here goes (From 5 Ideas About The Future of Work):

Workers should be treated like adults. Many organizations pay people well, but treat them like children with far too many rules and processes.

Your location, clothes, and hours matter less than your output. It’s common to reward people who come in early and stay late, but what does that have to do with their work performance? Not much. We all want to be judged fairly for our output, and this should include the possibility of being productive when remote.

You can escape from email and meeting hell. The banes of modern work are email and meetings but it doesn’t have to be this way. WordPress.com has proven it.

Hire by trial. There is no scientific evidence that resumés and interview loops are effective methods for hiring staff. The job interview process itself is dubious, since few interviewers are truly skilled at doing it without bias. WordPress.com hires by trial – you audition for a job, allowing both parties real exposure to the talents and limitations of the other.

This is a lot to absorb or believe. Which is why I wrote a book about it.

The following ideas were themes on my mind as I wrote the book:

There is no innovation without experimentation. Many people talk about wanting big ideas, but it’s rare that talk is matched with action.The grand frustration in the working world is stasis. Even if you don’t think what WordPress.com does can work for you, you must respect their willingness to experiment. The fact that they hired me, a veteran big company manager, shows their willingness to mix things up and learn from the results. Isn’t that what our leaders are supposed to be paid to do? If we should demand anything from managers, and perhaps from ourselves, it’s to take the first step, and learning from WordPress.com is an easy place to start.

Managers and executives in most workplaces are terrified of change despite what they say. They are unfamiliar with how to do experiments and learn from them.

WordPress.com/Automattic successfully defies conventional wisdom about hiring, offices, empowerment, incentives, management, intellectual property, hierarchy and more. They are the best case study for asking questions about work and what alternatives are on the horizon for the modern workplace.

Culture always wins over tools and salaries, but the business world is tone deaf to understanding culture.

Workplaces are buried in unquestioned and unproven traditions that should be tested and the story of WordPress.com raises those questions.

The justification for the subtitle (The Future of Work) is that rather than prescribe 5 dubious commandments like many business books do, we need to explore an actual example and have an expert (me in this case) bring their expertise to bear in the reporting. This approach reveals different lessons depending on the reader’s own experiences. I didn’t know of a management books like this so I felt I should I write it. The Year Without Pants has been criticized for not being prescriptive enough, which was by design. If I’m mostly prescribing, I’m failing to capture what the reality of this kind of workplace was like.

Did working remotely really work?

Yes, but I don’t advocate that it’s for everyone. But I do advocate empowering employees to experiment for themselves in how best to be productive, including trying remote work.

But you should recognize that most of us already do significant work remotely today. Consider this: what % of your working day is spent working with co-workers through a computer screen? I’d guess it’s 30-60%. In any of those moments you could be anywhere on the planet and do the same work. And the rest of the time is mostly in meetings we all complain about anyway. What is it we’re so afraid of to even give remote work a try? It’s an insane paradox. We hate things about work, but we defend those very same things whenever an alternative we haven’t even tried is proposed.

A good, collaborative team that likes their work and has clear goals can do excellent work remotely. If a team is neither good, nor collaborative, it’s the fault of management, which has nothing to do with working remotely or not.

But what about Yahoo banning remote work?

Yahoo has been a company in crisis for years: why are we using them as an example for emulation? Same for HP. Culture change, even in our supposed high tech high paced world, is slow. Many workplaces still require everyone to wear suits and skirts, and arrive at 9am, despite there being zero data this makes anyone happier or more productive.

This is a central question of the book: when was the last time you put your workplace traditions to the test? Is there really a rational basis for your assumptions about how work is best done?

How can I convince my boss to let me work remotely?

Two steps. 1. Do great work and get a great performance review. 2. Ask to try working remotely on a trial basis (perhaps one or two days a week). If in a month your performance is just as good, ask to continue. No good boss would refuse a request from a great worker than has no threat to worsen their performance.

If your boss is afraid to try, or can’t because of official policy, send them a copy of The Year Without Pants or Remote. Or look for a remote friendly company to work for, there’s a list of 100% remote companies here and hundreds more with liberal remote work policies.

Did working without email really work?

Yes, but I don’t advocate it’s for everyone. I do advocate it’s everyone’s job to look for and experiment with better ways of being productive, including communication tools other than email. If you try something and it fails, that’s one thing. But not to try at all? That’s shameful, especially if your organization claims to be progressive.

For within team interactions email has major limitations. Chapter 15 of the book, titled The Future of Work Part 2, documents exactly how we worked on a daily basis and how it compared to an e-mail centric culture. The modern workplace has pushed email too far and we know it. There are alternatives for within team communication that are better, but few have tried them.

Fundamentally the culture of most organizations is bureaucratic, forcing employees to seek permission and to cover their asses in email, confusing politics with productivity (See Is There Life After Email? @ FastCompany). In a healthy autonomous culture the pressure on email, and communication, is much lower (See also: Is There Life After Email? @ FastCompany). I’d fix the culture in an organization before I worried about the tools.

Did the experiment of having a non-programmer team leader work?

Yes. It’s not a new experiment really as plenty of important companies are led by people who aren’t a a specialist in whatever the company does. Leadership and management are general, not specialized, skills. I think I can lead a team that does just about anything because of my ability to lead, and my interest in and ability to learn what I don’t know. Being an expert is not mandatory to be a leader, and is possibly a limitation in some cases. What matters is being able to make use of experts and synthesize their opinions into good decisions for projects.

What happened after you left WordPress.com?

Everything exploded!

No, that’s not true. Automattic and WordPress.com have been doing very well. WordPress.com is the 8th most popular website in the U.S. The book closes with my departure (May 2012) and the team structure with leads and all has continued to this day. Many of the folks who were on my team became leads on other teams which was nice to see. Automattic currently has more than 210 employees and expects to grow at a similar fast pace this year (they’re hiring btw).

When the book released I was invited to speak at the 2013 Automattic company meetup to talk about the book. Most employees seemed to like it and I’m still friends with many of them. It’s a strange thing to have a book written about a place you work, and I understand that feeling.

Would the virtual, self deterministic org model work for a company that needs to market it’s products?

First, many organizations are dysfunctional. I don’t think the traditional ways organizations are structured set a high bar – it’s an assumption that it ‘works.’ The Jetpack project (chapter 17, ) demonstrated my team’s ability to launch a specific product on a specific day. Our team worked well together and working on a deadline turned out not to be any more challenging than it would have been for a traditionally managed company, and perhaps it was easier to achieve since we had far less politics to put up with.

Q. How can an existing company either accommodate or make the transition to being distributed?

For general advice see How To Change A Company. It’s the best advice for any kind of change to any organization. Change is hard because of culture, not technology. You have to start small, get it right, and repeat.

Chapter 15 of the book, titled The Future of Work Part 2, offers advice on the general way it happens: one person at a time. A worker has to say to their boss “hey, I can be just as, or more, productive if you let me work remotely. Let’s try it and see.” And then the boss has to say, “Yes”. If that experiment goes well, it will be repeated by others. This is the primary way change happens anywhere: two smart people agreeing to try something and then, when it works, agreeing to do it more and convincing others to follow. There’s no magic: just two open minded people.

It will usually be the youngest managers, on the youngest teams, at the youngest companies, that are willing to try new things first. They have fewer preconceptions and fewer things to fear. It’s no surprise most of the 100% distributed companies I’ve found are young software companies. But do consider that most remote workers on the planet are at large corporations (Aetna, American Express, IBM, etc.) where the financial payoffs of remote work have outweighed their fears. Someone at each of those companies had to be first to pitch the argument for experimenting with remote workers.

Of course a team leader, or an executive, can accelerate change if they have control over policies. But typically people with control over policies are conservative: they’ll wait for the existence of a highly productive and vocal minority with enough influence before even considering changing policy. If YOU, reading this, want to work remotely, it starts with you pitching your boss to give it a try. If they see it as a win for you to win by working remotely, they’ll naturally promote the idea.

If you want to see a post purely about how to do that pitch, leave a comment, or submit the question here. (Also: My general advice on pitching ideas).

Q. How can distributed work scale?

It already has. As mentioned above, most of the remote workers on the planet are at large corporations (Aetna, American Express, IBM, etc.). The U.S. space program in the 1960s employed 250,000 people in dozens of cities across the country. Every major armed force in history did most of it’s fighting in remote units. We have countless examples of large scale remote work. Think of the telegraph and the telephone, which allowed people hours apart to work together and collaborate. Remote work is old, but our fears cloud our memories. Microsoft, Google, and hundreds of companies have people working in different offices who magically are able to get work done without always sharing the same physical space.

Automattic is currently about 200 people. I could easily see the company reach 1000 people, with 5 product units each with about 200 people in them. Everything within those units would be much the same as it is now. Continuous deployment is part of how Automattic works and it helps with scale: since new ideas launch regularly you rarely have large dependencies between teams. The challenge with scale is for leaders of each unit, assuming they existed (and the units were not self-organizing collectives as some people theorize as ideal), to avoid the traps of middle-management, and maintain the same employee driven autonomy the company has now, while keeping the company lined up on strategy.

The history of work is useful here too. Read about the U.S. civil war or WWII or the Peloponnesian War. Armed forces in the grand wars of the past were intensely distributed, with thousands of soldiers working on what was supposed to be a singular strategy, separated by enormous distances. Messages were sent by runners and horses: ridiculously slow compared to Skype or SMS. My point is that there are plenty of examples of large scale distributed work if you look for them. My success and failures described in The Year Without Pants rarely hinged on my team being distributed or not.

Of course most companies fail. Most projects fail. We give a disproportionate amount of attention to absurdly successful things. If WordPress or Automattic fails in some significant way my first thought would not be to question the fact that they’re distributed, and the book does critique other elements of the company and the culture appropriately.

It’s rare for a “business” book to involve the journalist taking a full time job. How did you approach this project?

I approached the project journalistically inspired by NewJack and Down and Out In Paris and London. I wanted to report on a place from the inside, but from the first person, not third. I’m often disappointed by books about organizations where the writer never gets their hands dirty: how can you know the heart of a place if all you do is observe? I believe you have to participate to best capture an experience. To minimize betraying the trust of the team I lead, I chose to focus on my story and perspective, minimizing the need to report on private conversations or personal issues. Also working remotely made focusing on my story natural and fitting for the project.

Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.

— Janet Malcolm, American journalist and author (b. 1934), in The Journalist and the Murderer

We forget that all the books we read about real people and real organizations required someone to get inside and report on it to the rest of us. I don’t agree with Malcolm that journalists are exclusively immoral, but they frequently must choose between giving the reader, or the subject, the benefit of the doubt. You should think carefully about the books or articles you read in this respect.

(Some answers originally posted here)

What question did you want me to answer in the book that I didn’t cover? Leave a comment and I’ll add it to this post.

February 23, 2014

Should you ban Woody Allen’s films?

The resurfacing of Woody Allen’s past is sad from many perspectives, amplified by how a daughter and a family are still struggling, very publicly, to deal with events that took place decades ago. I’ll leave the conclusions for you to draw, as my question in this post is a practical one. Should you ban an artist’s work based on their personality or unethical behavior? Assume for the moment that the worst, however you define it in The Allen/Farrow case, is true – what does that mean about Allen’s work?

Animal New York recently published the definitive guide to never watching Woody Allen again, and it offers film suggestions based on each film in the Allen canon. The suggestions are inspired and thoughtful.

But what of the hundreds of other artists and creators who were criminals or ethically challenged?

The list includes: Michael Jackson (accused of child abuse), Norman Mailer (stabbed his wife), Picasso (womanizer), Henry Ford (anti-semite), Steve Jobs (abandoned his first child), Coco Channel (links to Nazi party), Thomas Edison (electrocuted animals to death for marketing), Volkswagen Beetle (designed by Nazi party), BMW (used slave labor), Thomas Jefferson (slave owner), Satellites and rockets (major innovations by (former) Nazi party members), James Watson (co-discoverer of DNA and quoted racist), Mark Wahlberg (assault/attempted murder), Dick Chaney (DUI), Gus Van Sant (DUI), Tim Allen (DUI, Cocaine trafficking), and the list goes on. I’m not equating any of these acts with each other or with child molestation, but merely establishing a landscape of works made by people with dubious ethical histories.

If you ban art because of the artist, it follows you’d ban engineering because of the engineer. So turn that electricity off. Stop driving that BMW or Volkswagen you love. Drop that iPhone. Ban the use of genetics in science.

Banning the work of someone you despise is far easier to do while in ignorance of the hundreds of created works you used every day with no knowledge about their origin. Scratch the surface and you’ll find multitudes of dubious characters behind the things you love and depend on.

Banning things is a negative act. It’s intended to hurt someone, or prevent something, but it does little to help other people who may have been, or will become, victims of the actions you despise. Banning things often gives ideas and their creators more power, not less, than simply ignoring them or, more progressively, taking actions for positive change against the thing you think is wrong. Banning Chick-A-Flick because the owner is a jerk does far less to help equal rights than volunteering your time or money to help one of the many groups actively working for positive change.

Instead of banning Woody Allen, or whatever creator you have issues with, do something to support organizations working for progress on the issue you care so much about. In the case of Dylan Farrow, you should support groups like RAINN, a charity that helps children and families victimized by abuse. This will do far more good for the world, and for you, than banning hundreds of works ever could. The act of banning is stuck in the past, instead take actions that help the future.

February 21, 2014

Why I Loved Webstock and What Organizers Can Learn

Last week I had the pleasure of speaking for a second time at Webstock in Wellington, New Zealand. Natasha Lampard, Mike Brown and all the organizers exemplify many of the great things event organizers should strive to achieve. They run an amazing event and as someone who writes often about speaking and events that have speakers, I wrote up notes on what they did so well.

Like great design, a great event is notable in large part for what you don’t notice. It takes far more work to make things seamless and natural. They do an amazing job of event planning and organizing and I wanted to highlight some lessons other events can learn from what they’ve done.

1. Single track events force quality

By only having a single track of speakers Webstock places big bets on who they invite. Any event with multiple tracks is choosing quantity over quality, as no organizer can spend much time selecting and supporting dozens (or hundreds) of speakers. Therefore the best events are almost always single track events and afford the deepest experiences for attendees. It means the organizers are investing heavily in a singular, crafted, shared experience, making it easier for attendees to talk to strangers and make new friends. The speaker list for 2014 was excellent and I was honored to be on the roster.

2. Great venues create energy

This year Webstock was at the St. James Theater in Wellington, a grand theater with two balconies. I can tell you as a speaker I do my best work in rooms built for speaking, which is what theaters are. No matter how fancy a hotel event space pretends to be, since the rooms are designed for multiple-purposes the acoustics, the lighting, and the energy always suffers. But in a theater, especially one with as much design detail as this one, wow.

The addition of a DJ spinning tracks (and not too loud) during registration and before talks began helped set the vibe before the event even officially began.

3. Speakers Are The Stars

It’s shocking how many conferences forget that speakers are the stars. Most conferences center on a series of speakers speaking: shouldn’t choosing the speakers and helping them prepare to do a great job be the most important thing organizers do? You’d think so. But often speakers are forgotten in the logistical shuffle of running a major event. I’m not suggesting speakers should be egotistical jerks (I suggest the opposite actually), but simply that their contribution is the most central one to the attendees experience of the event and should be treated as such.

Webstock does an exemplary job of making sure speakers are well taken care of. From the invitations, to detailed emails about what to expect and how to prepare, they clearly apply design thinking to how help speakers do their best performances. Demographics on attendees and videos of past lectures are provided.

All speakers were invited out to a special evening to socialize, a great speaker perk for any event. Speakers need help to make connections and friendships and a speakers dinner is an easy way to build camaraderie that will carry forward into the event itself. The organizers took us to the amazing Boomrock, a stunning ranch on the side of a mountain, where we shot rifles, threw knives and fired arrows (not at each other of course), building our appetite for an amazing meal overlooking the ocean. They made sure we all had a great experience together doing something memorable and unique to where we were in the world.

Webstock ’14 had diverse and well curated topics. For a web/tech event 25-30% of the talks were not strictly about the usual topics of design, engineering or technology. I spoke about the future of work, Derek Silver spoke about the meaning of life, Anne Hellen Peterson talked about media and gossip. The event brought in a wide lens of stories and perspectives that because of their careful choosing, fit together brilliantly (afforded by having a single, curated track).

4. They put love and style into the details

From the first email I got from Natasha, it was clear these organizers are smart, funny, passionate and inclusive. This is a passion project for them and they want as much of their energy and excitement to rub off on everyone involved, and it works. Natasha is a fantastic and entertaining writer, even in the many typically dry procedural emails that come with event organizing, and unlike any event I’ve ever been to I smiled and felt energized every time I had contact with her. It’s a little thing in the grand scheme, but little things matter. I wanted to do a great job for them simply because of how much they seemed to care.

Little things they did right:

Great signage everywhere, well branded and on theme (note the visual references to the St. James theater)

Attendee badges are easy to read (and double sided, since they often flip over – more badge advice)

Talk lengths 30 minutes or less

High quality and healthy food

Choosing volunteers who are excited to be there and genuinely interested in helping peopple

An opening high energy 5 minute video, with a rocking soundtrack, highlighting all the speakers (each getting natural applause), the venue, the organizers and the audience (the closing text in the video said, simply, ‘we love you’). What a simple way to get the crowd’s energy up before any of the speakers take the stage. I was the opening speaker and their brief, but energetic, opening, helped me do a good job in the lead off slot.

One way to think about conferences is that they’re really a form of party, and for a party to go well requires attention not only to detail, but to the right details. Webstock gets it right in so many ways. Most events can learn much what Webstock does so well.

Other write-ups about Webstock:

Webstock 2014, Rattling the cage

Webstock 2011 was amazing

Webstock 2014 highlights (video)

Mind-spa Webstock 2014

Webstock 2014: notes from Day 1

February 20, 2014

Speaking In Portland next week (Thurs/Fri)

Hi folks. Just a quick post about some speaking dates next week in wonderful Portland, Oregon.

Thursday, 2/27 6pm at 10up - I’ll be talking about The Year Without Pants and then out for drinks/snacks with attendees. RSVP.

Friday, 2/28 at IntegratED – As part of this conference on education and technology, I’ll be speaking twice, once about public speaking and the closing keynote about the future of Work. Registation

Hope to see you. Cheers.

February 14, 2014

Buy The Year Without Pants 50% off (Ebook / DRM Free)

For Valentines day O’Reilly Media is doing a special promotion for The Year Without Pants (published by Wiley).

You can buy the digital version of the book for 50% off – and it’s DRM free (multiple formats, lifetime access, free updates).

Deal ends at midnight. Happy Valentines day.

February 6, 2014

Why Speed Reading Is For Fools

Life is not a race. Speed is good for things you want to get past, not for important things you enjoy. “It was an efficient meal.” “I had a quick life.” If you are doing something meaningful you’d want the experience to last. You would try to savor and consider every single moment to extract the maximum value from it.

Sometimes people brag to me about how many books they read each year. “I read 40 books” or “I read 60 books.” My first thought is they’re probably reading the wrong books. Or reading them the wrong way. Any book I feel the urge to speed through means it’s either not very good or I’m not very interested.

You could drive by the Grand Canyon at 100mph. “I saw 20 landmarks today.” “Oh, really, I saw 45″. But did they see anything? Did they experience anything? They’d have felt and learned far more if they had tried to do far less. You can race through a foreign nation checking items off a list of “must-sees” or you can dig in deeper and actually experience something of the culture you’ve taken so much trouble to go and visit. Books, art, movies and meals are no different. Two people can see the same exact thing in the same moment and have entirely opposite experiences simply because of how quickly or slowly they pay attention.

Intimacy is slow. Depth takes time. If you want intimate thoughts, intimate friends, intimate experiences it can’t happen quickly. Some people tell me they have great reading comprehension even at speed. They challenge me to test them about information from the book. But I don’t care what they can recall. Being able to recall a fact does not mean they’ve considered it, examined it, or used it to change their thinking or how they feel about the world. Reading comprehension does not equal reading wisdom. Comprehension is for a test, wisdom is for your life.

Volume is easy. Speed is easy. It’s quality that’s hard. It’s thinking that’s a challenge. “I read a 1000 books a year.” Who the hell cares? If you are doing it that fast it is an activity far different than what I do when I’m reading a book. Books aren’t just trophies to hang on your wall or to stroke your ego with.

Good writing, or good anything, offers us the chance to pause and reflect. It’s good to read a good book slowly. To take time to consider the new ideas you’re taking in. To ask questions with other smart people about what you’re reading as you read it. If you’re reading to learn you want to read thoughtfully. If you are reading good books you will be engaged and have little concern about how long it’s taking or how long they are. “The book is 500 pages? Forget it, I don’t have time.” That’s insane. You’d rather read 5 100 page books that suck? Would you reject a 7 course meal at your favorite restaurant in favor of a 3 course one? If it’s a great book you should be glad the experience can be longer. It’s bad books of any length that should be avoided. It’s quality not quantity that matters.

I remember as a college student reading to study for tests. I’d read and read with the singular intention of trying to extract answers to the questions I thought would be asked. This was shallow reading. Many books were unworthy but even for ones that were I raced past the most valuable opportunities those books offered as I was hunting something much more shallow. What are you hunting for? You should slow down when you find it. If you never find it, change how you hunt.

Related: Attention and Sex and Why It’s Ok To Buy Books But Not Read Them

February 5, 2014

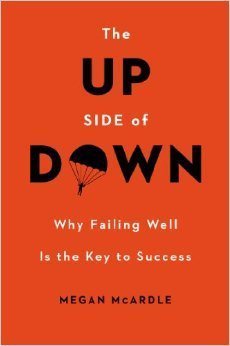

(Book Review) The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well Is the Key to Success

I read a prerelease copy of The Up Side of Down: Why Failing Well Is the Key to Success from Viking Adult.

McArdle writes well but the structure and pacing of this book was uneven. Twice during reading I double checked the title of the book to make sure I hadn’t made some mistake about what the book’s title was. Some chapters go too deep into singular, and not quite interesting enough, examples in a style that had a certain self-centeredness about them, as if they thought they were the star of their own show. I simply asked myself as a reader “where is this going and why are we still talking about this 10 pages later?” too often.

I wasn’t surprised to learn in the acknowledgements that the balance of the book was based on writings previously published for The Atlantic and other magazines. This is not a ding about reusing work, as I don’t care where the pages are born from provided the book works as a coherent whole, or is described as a collection, and neither was the case. There are also many political (Russia, America) and economic failure examples (debt, taxation, regulation, conservatives/liberals), which in retrospect fits McArdles wheelhouse as a journalist, but not my interests as a general audience reader interested in failure (which is what the title suggests is who the book is for).

On the positive side there are pockets of solid storytelling and useful commentary on rethinking failure here, it’s just not consistently delivered and compared to the many excellent books for the general reader already published on rethinking our assumptions about failure (see list below) I can’t justify recommending this book and its narrative wanderings, unless you’re a fan of McArdle’s writing (in which case you may have read some of this before) or you have a primary interest in failure in economics and economic policy.

She does correctly nail certain nuances often overlooked. She observes how we reward pundits for hyperbole rather than accuracy in prediction (A point Nate Silver’s Signal and The Noise also emphasized), and the unavoidable failures of faith in testing of any kind (See Dangers of Faith of Data). She captures how much randomness there is in why things fail or succeed (The films Waterworld vs. Titanic is one example) and points out how the Mona Lisa only rose in popularity after it was stolen (and returned), which has nothing to do with the quality of the painting itself. These points are well made and insightful.

And she explores a standard roster of studies from academia like The Stanford Marshmellow test on self control and the Peter Skillman Spaghetti bridge challenge (which coincidentally also involves a marshmallow) that showed how kindergarden children outperformed adults in a design challenge simply because they were the most willing to fail fast and learn from it. She also references Carol Dweck’s work on Fixed vs. Growth mindsets which is a concept rising fast in the corporate world as the latest panacea (for those wanting to replace their obsession with Myers-Briggs). Cognitive Bias, one of my favorite subjects, gets coverage too. Had these themes been more central to the book it would have faithfully lived up to the title, been a better read and easier to recommend.

Here’s my short list of related books I’d recommend:

Being Wrong Adventures in The Margins of Error, Kathryn Schulz: This is probably the layperson oriented book about how to look at failure differently that you’re looking for, covering most of the bases of stigma of failure, mental models, while keeping the focus on individuals, and ordinary life situations.

To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design, Petroski: If you’re an engineer or builder of any kind this book is for you. It’s a short book with case study exploration of several different famous failures (Tacoma Narrows bridge, Challenger space shuttle, etc.). There’s limited analysis of how to prevent failure, but the message of how we primarily learn from failure is made clear.

The Logic of Failure, Dietrich Dörne - If you are a manager or leader Dörne focuses on how data can lead you to the wrong conclusions. It’s not the most entertaining book but it’s one of the deepest for understanding the nuances of how what appears to be reasoned decision making based on data can set you up to fail.

You are Not So Smart, McRaney: The best single book on Cognitive Bias. It’s a series of short articles, each covering a different bias. It doesn’t go into how to overcome them, and he can be loose with the references and supporting arguments, but since Cognitive Bias has a huge role in why we fail understanding them is a great place to start.

Deep Survival, Gonzales: an examination of who survives in disasters and dangerous situations. It’s not specifically about failure, but about how we handle crisis, and what habits and patterns of thinking matter, or can get you killed. McArdle briefly, and positively, mentions it in the Up Side of Down.