Brent Marchant's Blog, page 124

January 28, 2016

‘Kaballah Me’ presents a blueprint for living

“Kabbalah Me” (2014). Cast: Steven E. Bram, Miriam Bram, Rabbi Stuart Shiff, Dr. Jane Bram, William Bram, Rabbi Adam Jacobs, Rabbi Robert Levine, Rabbi David Ingber, Rabbi Beryl Epstein, Rabbi Chaim Miller, Shannan Catlett, Elchonon Kranz, Rabbi Avraham Sutton, Rabbi Efim Svirsky, The Skolyia Rebbe, Bob Potter, Rabbi Yitzchak Schwartz, Rabbi Tzadok Cable, Rabbi Yom Tov Glaser, Rabbi David Aaron, Rabbi Adam Sinay, David Friedman, Benzion Eliyahu Lehrer, Yehudit Goldfarb. Directors: Steven E. Bram and Judah Lazarus. Screenplay: Steven E. Bram, Judah Lazarus and Adam Zucker. Story: Steven E. Bram and Rabbi Adam Jacobs. Web site. Trailer.

The search for meaning in life can be a lonely and frustrating one. For many of us, it seems like there must be something that gives it direction and purpose. But what is it? And how do we find it? Those are among the issues addressed in the enlightening DVD, “Kaballah Me.”

For years, New York-based filmmaker Steven E. Bram felt something was missing from his life. Though he was materially successful and a happily married father of two, he had an uneasy sense that his existence came up short somehow. To compensate, he pursued a variety of “experiences,” from going to Grateful Dead concerts to skydiving to devotedly following the New York Jets, all in hopes of attaining some sort of meaning. But the enlightenment he sought always seemed to elude him. And then, in the wake of 9/11 (which impacted him personally) and with his 50th birthday looming, Steven’s longing to resolve that nagging, nebulous emptiness grew ever stronger. But how? Interestingly, the process began somewhat innocuously at an unlikely location.

While attending a sporting event at New York’s Madison Square Garden, Bram spoke about his quest with a friend, who recommended someone who might be able to help, Rabbi Stuart Shiff. The suggestion surprised Bram, but it also piqued his interest, for, even though Steven grew up in a Jewish household, his connection to his heritage was primarily secular, not religious. But, with no other option readily available to him, he decided to give it a try.

Rabbi Shiff advised Bram that he should look into Kabbalah, the study of Jewish mysticism, a topic about which he (like many of his peers) knew virtually nothing. In fact, about all he knew was that it was a discipline that had been popularized by a number of celebrities in recent years (most notably Madonna). However, the more the rabbi spoke about it, the more intrigued Bram became. Rabbi Shiff recommended that Steven meet with Rabbi Adam Jacobs, a Kabbalah instructor and managing director of the New York Aish Center, for more information. And, after meeting with Rabbi Jacobs, Bram was off and running.

Jacobs recommended that Bram meet with members of New York’s orthodox Jewish community to learn more. This included meetings with orthodox relatives whom Steven knew of but had never met, as well as visits to the facilities of Kabbalah-related organizations. And the more he learned about the subject, the more he could see there were no easy answers when it came to understanding it.

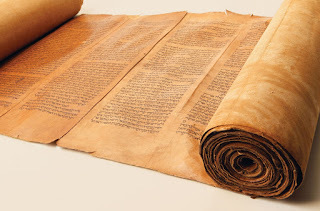

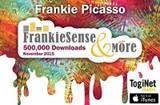

An ancient Torah, as seen in the engaging documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

An ancient Torah, as seen in the engaging documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Why the complexity? In large part, it stemmed from the fact that experts on the subject had widely divergent views about what constitutes Kabbalah. To begin with, most followers fall into one of two principal camps. For some, Kabbalah is an intrinsic aspect of the religion with which it’s associated (even if many of the faith’s practitioners are themselves unfamiliar with it). For others, however, it’s a philosophy all its own that can be readily separated from its theological roots and studied independently, regardless of whether one is Jewish. So, based on this fundamental distinction alone, it’s easy to see how someone could easily become confused about the subject. But, in light of the many elements the discipline embodies, the study of Kabbalah is a lot to take in, especially for someone just starting out with it.

To find the right fit, Steven chose to investigate both of the foregoing approaches. With regard to Kabbalah as a purely philosophical pursuit, he visited New York’s Kabbalah Centre, an organization offering study of the subject regardless of religious affiliation. Ironically enough, he also conversed with several rabbis, such as Rabbi Yitzchak Schwartz, a former Texas cowboy-turned-Kabbalah teacher, who urges the curious to take up their study of the subject even if they aren’t interested in adopting the related theological practices.

By contrast, Bram also investigated Kabbalah-related organizations and events that fully embrace the discipline’s religious aspects. This included visiting traditional Jewish bookstores, festivals and study centers in Brooklyn and attending a gathering of about 100,000 orthodox seekers at New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium. He also looked into some of Judaism’s time-honored practices, like keeping kosher.

The act of lighting candles in a Kabbalah ceremony, as seen in filmmaker Steven E. Bram’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

The act of lighting candles in a Kabbalah ceremony, as seen in filmmaker Steven E. Bram’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Bram’s decision to examine both approaches was important for reasons other than keeping an open mind; he also had his marriage and family to consider. Even though Steven and his wife Miriam were married in a synagogue, the couple had never practiced the rituals and traditions of their faith. Miriam, in fact, was a student of Buddhism and a yoga practitioner, but her interest in these matters was primarily spiritual, not religious. Consequently, she was concerned about the direction Steven’s quest would take. While she applauded his desire to find meaning, she wasn’t interested in joining him if he were to become religiously observant. She openly and candidly wondered what impact such a move might have on their marriage and in their role as parents, so Steven had to balance these considerations while pursuing the fulfillment of his own needs.

After investigating all of the resources New York had to offer, Steven still felt unfulfilled. He decided that, if he were to really find out everything Kabbalah had to offer, he needed to immerse himself in it, to visit where it all began – Israel. And so, with a list of recommended sites and contacts in hand, he traveled to the Holy Land, visiting the Sea of Galilee, the Kabbalah center of Tzfat, a joyous Kabbalah celebration in Meron and Jerusalem’s Western Wall. He met and spoke with Kabbalah instructors and practitioners from all walks of life, in addition to dancing, praying and taking ritualistic baths (mikvahs).

Filmmaker Steven E. Bram (center) dances with orthodox Jewish men while on a pilgrimage to Israel, as depicted in the director’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Filmmaker Steven E. Bram (center) dances with orthodox Jewish men while on a pilgrimage to Israel, as depicted in the director’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

As Steven engaged in this spiritual odyssey, both at home and overseas, friends began to question his actions and motives. Some even thought he went over the deep end and joined a cult. But, thanks to this journey, he emerged a changed person with a renewed outlook on life. The meaning that had always seemed to escape him no longer seemed so elusive. And he had Kabbalah to thank for it.

So what exactly did Bram discover? He learned a set of principles for guiding him on his journey through life. And, as a closer look at those precepts reveals, many of its core concepts closely resemble those found in the practice of conscious creation, the means by which we manifest the reality we experience through our thoughts, beliefs and intents. Those parallel principles include the following:

Kabbalah , like conscious creation, is a journey of personal discovery. Just as conscious creation urges us to comprehend the beliefs that manifest our respective realities, Kabbalah likewise encourages its followers to look for meaning in their lives. Specifically, Kabbalah prompts the search for what one’s existence is all about and what holds it together. This requires finding an expanded sense of consciousness and connection on a deeper, soul level. It involves looking inward, into the same realm where our beliefs – the drivers of conscious creation – reside and, consequently, coming to understand those intents and their ramifications. Our acknowledgment and comprehension of those beliefs bring to us a greater overall awareness, and the more receptive we are to it, the more we get out of it. In that sense, conscious creation, like Kabbalah, is an act of receiving knowledge, an acceptance of our true selves and how that’s reflected in the reality we experience. In fact, the word “Kabbalah,” which means “receiving,” embodies that very notion in its name.

One must change the inside to change the outside. The aim in both disciplines is to learn about where we’re coming from. Conscious creators call this understanding our beliefs, while Kabbalists refer to it as learning the language of the heart, but, in both cases, the process is essentially the same. And, if we’re intent on bettering our existences, this is where we must start, regardless of which practice we employ. Implementing change calls for executing shifts in consciousness (or altering our beliefs), a process that requires us to be honest with ourselves. It may take time – perhaps even an entire lifetime – to get results. In many ways, both disciplines involve an evolutionary process (what conscious creators would call “a constant state of becoming”), with the end of each “chapter” marking the beginning of a new one (and, one would hope, one that reflects the materialization of those hoped-for changes).

Kabbalah can be applied in many different ways. Just as conscious creation can be employed to any endeavor, so, too, can Kabbalah. In fact, the film illustrates this, showing how it can be applied in such diverse pursuits as art, meditation, and healing and nutrition. But, then, that shouldn’t come as any surprise, since all of those undertakings are outer expressions of our inner world.

Kaballah involves finding a balance between our internal and external lives, harmonizing “flow” and “structure” (i.e., consciousness and manifestation). In one of Bram’s more engaging conversations, he discusses the significance of this principle with Rabbi Yom Tov Glaser, also known as “the surfing rabbi.” As an avid fan of riding the waves, Glaser waxes philosophically about his passion and how it – like any venture pursued through Kabbalah – calls for its practitioners to make use of this concept. “Flow” represents the unimpeded stream of consciousness from our inner selves into the outer world, while “structure” accounts for the physically manifested shape it takes in external reality. To put this idea into context, Glaser offers an excellent analogy. He asks viewers to think of the ocean: This vast body of water, with its myriad ebbs and currents, symbolizes our consciousness (flow), while the shoreline, with its inherent defining effect, represents the concept of manifestation by giving shape (structure) to the ocean. The potential is thus made manifest as the tangible. Again, this is a notion that can be employed in virtually any aspect of life through Kaballah. Or, as another of Bram’s interview subjects puts it, the purpose behind this practice is “ending in actuality, not theory,” no matter how it is applied.

Kaballah requires us to become reacquainted with our intrinsic sense of connection. This is crucial, because it’s something many of us have fundamentally forgotten. The problem is that we have allowed ourselves to become held hostage by our ego selves, our sense of “I,” so much so that we often fail to recognize our connection to our larger, expanded selves. However, this sense of separation must be dispensed with if we are ever to rediscover our lost sense of connection. This is one of several significant misunderstandings of the Universe that we must cope with if we ever hope to get ourselves back on track.

A man blows a ceremonial horn known as a shofar, as seen in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

A man blows a ceremonial horn known as a shofar, as seen in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Of course, Kaballah’s similarities to its contemporary metaphysical cousin don’t end there. It also deals with such familiar conscious creation concepts as choice and free will, living in the present moment (and not worrying about tomorrow), living in community and not just individually (the impact of co-created mass events), figuring out the reasons for things (understanding our manifesting beliefs), becoming aware of the qualities of our greater existence (including the existence of such attributes as different dimensions, reincarnation and “soul fragments”), and so on. In fact, in light of all this, then one might successfully argue that conscious creation, at its core, is little more than a modern restatement of this time-honored philosophy.

Considering how long Kaballah has been around, and given the relative obscurity to which it had been relegated for so long, one might wonder why it’s experiencing such a resurgence at the moment. But, to answer that, one need only look at Bram’s own experience. As someone in middle life looking for the meaning that has long been missing from it, combined with the tremendous emotional impact of the 9/11 tragedy, it’s not surprising that something seemingly capable of filling that void would hold enormous appeal.

This is especially true in a world beset by as many challenges as we’re experiencing currently, both individually and collectively. For many of us, everyday existence often seems like more than we can bear. But, as several of the film’s interview subjects observe, “every light is preceded by a darkness, and the greater the darkness, the greater the shift that will come from it.” Some even contend that we’re now in the time of the “Double Darkness,” where it’s so dark we don’t even realize it’s dark. Perhaps that’s why so many Kabbalah seekers have come along now – to collectively implement the Tikkun – the “rectification” – to address these issues. We can only hope.

Pilgrims pray at Jerusalem’s sacred Western Wall, as depicted in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Pilgrims pray at Jerusalem’s sacred Western Wall, as depicted in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

For those seeking answers to life’s questions, “Kaballah Me” may offer just the ticket they’re looking for. The film presents its material in a clear, concise, easily understood manner, with a highly personalized approach, taking lofty notions and bringing them down to a readily accessible level (kind of like what Kaballah itself is intended to do). It also infuses a great deal of humor and heartfelt emotion in taking viewers to its ultimate destination, providing a fun-loving ride for the journey. Think of it as an entertaining philosophical travelogue, and you get the idea.

In addition to the main film, the DVD includes an excellent selection of bonus features. Through a series of short vignettes, viewers are treated to additional material covering a variety of intriguing subjects, such as Kaballah’s relation to (and interpretation of) oneness, science, and good and evil. There is also a segment on the role of women in Kabbalah, extended footage of the Kabbalah celebration in Meron and a moving meditation on opening the heart.

As every architect knows, a good blueprint is essential to erect a sturdy, properly functioning finished structure. Unfortunately, many of us haven’t done the same for ourselves in building the structures of our lives. Taking such a haphazard approach has often left us to construct the frames of our lives without direction, purpose or clarity. But, with the aid of the ancient wisdom of Kaballah (and its contemporary counterpart), we have an opportunity to create an existence characterized by satisfaction, joy and fulfillment. So go grab that metaphysical tool belt – and get to work.

Copyright © 2015-2016, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

The search for meaning in life can be a lonely and frustrating one. For many of us, it seems like there must be something that gives it direction and purpose. But what is it? And how do we find it? Those are among the issues addressed in the enlightening DVD, “Kaballah Me.”

For years, New York-based filmmaker Steven E. Bram felt something was missing from his life. Though he was materially successful and a happily married father of two, he had an uneasy sense that his existence came up short somehow. To compensate, he pursued a variety of “experiences,” from going to Grateful Dead concerts to skydiving to devotedly following the New York Jets, all in hopes of attaining some sort of meaning. But the enlightenment he sought always seemed to elude him. And then, in the wake of 9/11 (which impacted him personally) and with his 50th birthday looming, Steven’s longing to resolve that nagging, nebulous emptiness grew ever stronger. But how? Interestingly, the process began somewhat innocuously at an unlikely location.

While attending a sporting event at New York’s Madison Square Garden, Bram spoke about his quest with a friend, who recommended someone who might be able to help, Rabbi Stuart Shiff. The suggestion surprised Bram, but it also piqued his interest, for, even though Steven grew up in a Jewish household, his connection to his heritage was primarily secular, not religious. But, with no other option readily available to him, he decided to give it a try.

Rabbi Shiff advised Bram that he should look into Kabbalah, the study of Jewish mysticism, a topic about which he (like many of his peers) knew virtually nothing. In fact, about all he knew was that it was a discipline that had been popularized by a number of celebrities in recent years (most notably Madonna). However, the more the rabbi spoke about it, the more intrigued Bram became. Rabbi Shiff recommended that Steven meet with Rabbi Adam Jacobs, a Kabbalah instructor and managing director of the New York Aish Center, for more information. And, after meeting with Rabbi Jacobs, Bram was off and running.

Jacobs recommended that Bram meet with members of New York’s orthodox Jewish community to learn more. This included meetings with orthodox relatives whom Steven knew of but had never met, as well as visits to the facilities of Kabbalah-related organizations. And the more he learned about the subject, the more he could see there were no easy answers when it came to understanding it.

An ancient Torah, as seen in the engaging documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

An ancient Torah, as seen in the engaging documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.Why the complexity? In large part, it stemmed from the fact that experts on the subject had widely divergent views about what constitutes Kabbalah. To begin with, most followers fall into one of two principal camps. For some, Kabbalah is an intrinsic aspect of the religion with which it’s associated (even if many of the faith’s practitioners are themselves unfamiliar with it). For others, however, it’s a philosophy all its own that can be readily separated from its theological roots and studied independently, regardless of whether one is Jewish. So, based on this fundamental distinction alone, it’s easy to see how someone could easily become confused about the subject. But, in light of the many elements the discipline embodies, the study of Kabbalah is a lot to take in, especially for someone just starting out with it.

To find the right fit, Steven chose to investigate both of the foregoing approaches. With regard to Kabbalah as a purely philosophical pursuit, he visited New York’s Kabbalah Centre, an organization offering study of the subject regardless of religious affiliation. Ironically enough, he also conversed with several rabbis, such as Rabbi Yitzchak Schwartz, a former Texas cowboy-turned-Kabbalah teacher, who urges the curious to take up their study of the subject even if they aren’t interested in adopting the related theological practices.

By contrast, Bram also investigated Kabbalah-related organizations and events that fully embrace the discipline’s religious aspects. This included visiting traditional Jewish bookstores, festivals and study centers in Brooklyn and attending a gathering of about 100,000 orthodox seekers at New Jersey’s MetLife Stadium. He also looked into some of Judaism’s time-honored practices, like keeping kosher.

The act of lighting candles in a Kabbalah ceremony, as seen in filmmaker Steven E. Bram’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

The act of lighting candles in a Kabbalah ceremony, as seen in filmmaker Steven E. Bram’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.Bram’s decision to examine both approaches was important for reasons other than keeping an open mind; he also had his marriage and family to consider. Even though Steven and his wife Miriam were married in a synagogue, the couple had never practiced the rituals and traditions of their faith. Miriam, in fact, was a student of Buddhism and a yoga practitioner, but her interest in these matters was primarily spiritual, not religious. Consequently, she was concerned about the direction Steven’s quest would take. While she applauded his desire to find meaning, she wasn’t interested in joining him if he were to become religiously observant. She openly and candidly wondered what impact such a move might have on their marriage and in their role as parents, so Steven had to balance these considerations while pursuing the fulfillment of his own needs.

After investigating all of the resources New York had to offer, Steven still felt unfulfilled. He decided that, if he were to really find out everything Kabbalah had to offer, he needed to immerse himself in it, to visit where it all began – Israel. And so, with a list of recommended sites and contacts in hand, he traveled to the Holy Land, visiting the Sea of Galilee, the Kabbalah center of Tzfat, a joyous Kabbalah celebration in Meron and Jerusalem’s Western Wall. He met and spoke with Kabbalah instructors and practitioners from all walks of life, in addition to dancing, praying and taking ritualistic baths (mikvahs).

Filmmaker Steven E. Bram (center) dances with orthodox Jewish men while on a pilgrimage to Israel, as depicted in the director’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Filmmaker Steven E. Bram (center) dances with orthodox Jewish men while on a pilgrimage to Israel, as depicted in the director’s documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.As Steven engaged in this spiritual odyssey, both at home and overseas, friends began to question his actions and motives. Some even thought he went over the deep end and joined a cult. But, thanks to this journey, he emerged a changed person with a renewed outlook on life. The meaning that had always seemed to escape him no longer seemed so elusive. And he had Kabbalah to thank for it.

So what exactly did Bram discover? He learned a set of principles for guiding him on his journey through life. And, as a closer look at those precepts reveals, many of its core concepts closely resemble those found in the practice of conscious creation, the means by which we manifest the reality we experience through our thoughts, beliefs and intents. Those parallel principles include the following:

Kabbalah , like conscious creation, is a journey of personal discovery. Just as conscious creation urges us to comprehend the beliefs that manifest our respective realities, Kabbalah likewise encourages its followers to look for meaning in their lives. Specifically, Kabbalah prompts the search for what one’s existence is all about and what holds it together. This requires finding an expanded sense of consciousness and connection on a deeper, soul level. It involves looking inward, into the same realm where our beliefs – the drivers of conscious creation – reside and, consequently, coming to understand those intents and their ramifications. Our acknowledgment and comprehension of those beliefs bring to us a greater overall awareness, and the more receptive we are to it, the more we get out of it. In that sense, conscious creation, like Kabbalah, is an act of receiving knowledge, an acceptance of our true selves and how that’s reflected in the reality we experience. In fact, the word “Kabbalah,” which means “receiving,” embodies that very notion in its name.

One must change the inside to change the outside. The aim in both disciplines is to learn about where we’re coming from. Conscious creators call this understanding our beliefs, while Kabbalists refer to it as learning the language of the heart, but, in both cases, the process is essentially the same. And, if we’re intent on bettering our existences, this is where we must start, regardless of which practice we employ. Implementing change calls for executing shifts in consciousness (or altering our beliefs), a process that requires us to be honest with ourselves. It may take time – perhaps even an entire lifetime – to get results. In many ways, both disciplines involve an evolutionary process (what conscious creators would call “a constant state of becoming”), with the end of each “chapter” marking the beginning of a new one (and, one would hope, one that reflects the materialization of those hoped-for changes).

Kabbalah can be applied in many different ways. Just as conscious creation can be employed to any endeavor, so, too, can Kabbalah. In fact, the film illustrates this, showing how it can be applied in such diverse pursuits as art, meditation, and healing and nutrition. But, then, that shouldn’t come as any surprise, since all of those undertakings are outer expressions of our inner world.

Kaballah involves finding a balance between our internal and external lives, harmonizing “flow” and “structure” (i.e., consciousness and manifestation). In one of Bram’s more engaging conversations, he discusses the significance of this principle with Rabbi Yom Tov Glaser, also known as “the surfing rabbi.” As an avid fan of riding the waves, Glaser waxes philosophically about his passion and how it – like any venture pursued through Kabbalah – calls for its practitioners to make use of this concept. “Flow” represents the unimpeded stream of consciousness from our inner selves into the outer world, while “structure” accounts for the physically manifested shape it takes in external reality. To put this idea into context, Glaser offers an excellent analogy. He asks viewers to think of the ocean: This vast body of water, with its myriad ebbs and currents, symbolizes our consciousness (flow), while the shoreline, with its inherent defining effect, represents the concept of manifestation by giving shape (structure) to the ocean. The potential is thus made manifest as the tangible. Again, this is a notion that can be employed in virtually any aspect of life through Kaballah. Or, as another of Bram’s interview subjects puts it, the purpose behind this practice is “ending in actuality, not theory,” no matter how it is applied.

Kaballah requires us to become reacquainted with our intrinsic sense of connection. This is crucial, because it’s something many of us have fundamentally forgotten. The problem is that we have allowed ourselves to become held hostage by our ego selves, our sense of “I,” so much so that we often fail to recognize our connection to our larger, expanded selves. However, this sense of separation must be dispensed with if we are ever to rediscover our lost sense of connection. This is one of several significant misunderstandings of the Universe that we must cope with if we ever hope to get ourselves back on track.

A man blows a ceremonial horn known as a shofar, as seen in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

A man blows a ceremonial horn known as a shofar, as seen in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.Of course, Kaballah’s similarities to its contemporary metaphysical cousin don’t end there. It also deals with such familiar conscious creation concepts as choice and free will, living in the present moment (and not worrying about tomorrow), living in community and not just individually (the impact of co-created mass events), figuring out the reasons for things (understanding our manifesting beliefs), becoming aware of the qualities of our greater existence (including the existence of such attributes as different dimensions, reincarnation and “soul fragments”), and so on. In fact, in light of all this, then one might successfully argue that conscious creation, at its core, is little more than a modern restatement of this time-honored philosophy.

Considering how long Kaballah has been around, and given the relative obscurity to which it had been relegated for so long, one might wonder why it’s experiencing such a resurgence at the moment. But, to answer that, one need only look at Bram’s own experience. As someone in middle life looking for the meaning that has long been missing from it, combined with the tremendous emotional impact of the 9/11 tragedy, it’s not surprising that something seemingly capable of filling that void would hold enormous appeal.

This is especially true in a world beset by as many challenges as we’re experiencing currently, both individually and collectively. For many of us, everyday existence often seems like more than we can bear. But, as several of the film’s interview subjects observe, “every light is preceded by a darkness, and the greater the darkness, the greater the shift that will come from it.” Some even contend that we’re now in the time of the “Double Darkness,” where it’s so dark we don’t even realize it’s dark. Perhaps that’s why so many Kabbalah seekers have come along now – to collectively implement the Tikkun – the “rectification” – to address these issues. We can only hope.

Pilgrims pray at Jerusalem’s sacred Western Wall, as depicted in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.

Pilgrims pray at Jerusalem’s sacred Western Wall, as depicted in the documentary, “Kabbalah Me.” Photo courtesy of First Run Features.For those seeking answers to life’s questions, “Kaballah Me” may offer just the ticket they’re looking for. The film presents its material in a clear, concise, easily understood manner, with a highly personalized approach, taking lofty notions and bringing them down to a readily accessible level (kind of like what Kaballah itself is intended to do). It also infuses a great deal of humor and heartfelt emotion in taking viewers to its ultimate destination, providing a fun-loving ride for the journey. Think of it as an entertaining philosophical travelogue, and you get the idea.

In addition to the main film, the DVD includes an excellent selection of bonus features. Through a series of short vignettes, viewers are treated to additional material covering a variety of intriguing subjects, such as Kaballah’s relation to (and interpretation of) oneness, science, and good and evil. There is also a segment on the role of women in Kabbalah, extended footage of the Kabbalah celebration in Meron and a moving meditation on opening the heart.

As every architect knows, a good blueprint is essential to erect a sturdy, properly functioning finished structure. Unfortunately, many of us haven’t done the same for ourselves in building the structures of our lives. Taking such a haphazard approach has often left us to construct the frames of our lives without direction, purpose or clarity. But, with the aid of the ancient wisdom of Kaballah (and its contemporary counterpart), we have an opportunity to create an existence characterized by satisfaction, joy and fulfillment. So go grab that metaphysical tool belt – and get to work.

Copyright © 2015-2016, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Published on January 28, 2016 00:54

January 27, 2016

Visit the Movies with Meaning Page

Visit the new Movies with Meaning page on The Good Radio Network web site, available by clicking here. And check out my first Movies with Meaning radio segment on the Frankiesense & More radio show this Thursday, January 28, at 2 pm Eastern, available live or via podcast by clicking here.

Published on January 27, 2016 23:25

Check out Movies with Meaning!

I'm thrilled to announce that I have been named Movie Correspondent for The Good Radio Network and its Frankiesense & More radio show with host Frankie Picasso. Look for my regular Movies with Meaning blog posts on the network's web site, featuring movie-related news and reviews (the first one is now available here). And then tune in on the last Thursday of every month for my regular Movies with Meaning news and reviews segment on Frankiesense & More, available for listening live or on the show's downloadable podcast.

Published on January 27, 2016 00:05

January 21, 2016

‘The Big Short’ dissects a financial meltdown

“The Big Short” (2015). Cast: Christian Bale, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, Brat Pitt, Melissa Leo, Marisa Tomei, Finn Wittrock, John Magaro, Rafe Spall, Hamish Linklater, Jeremy Strong, Adepero Oduye, Tracy Letts, Byron Mann, Rajeev Jacob, Jeffry Griffin, Karen Gillan, Billy Magnussen, Max Greenfield, Margot Robbie, Selena Gomez, Anthony Bourdain, Richard Thaler. Director: Adam McKay. Screenplay: Charles Randolph and Adam McKay. Book: Michael Lewis, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. Web site. Trailer.

The Great Recession of 2008 is all too well known to a great many people. Much of the blame was placed on the collapse of the home mortgage market, and, at least superficially, that might be true. But what was behind that debacle, the underlying cause of an event that nearly brought the entire world’s economy to its knees? That’s what “The Big Short” seeks to explain.

In 2005, virtually everyone in the financial services industry was living high on the hog. Despite the losses that occurred in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the economy rebounded strongly in the time since that fateful day in 2001. Money rolled in as if it were on a perpetual upward spiral, a nonstop gravy train that most insiders thought would never end. People in the business partied like there was no tomorrow, celebrating the good fortune that was now being looked on as unending and matter of fact.

Many of those fortunes were made in the home mortgage market, a segment of the economy seen as rock solid dependable. But was it? As several astute financial analysts began to discover, the mortgage business looked like a disaster waiting to happen. The “bubble” that was forming in the housing market was getting ready to burst – and in a very big way. But, because most everyone in the business was so busy swilling champagne and spending money hand over fist, no one was paying attention to the fact that the mortgage market was built on risky investments that weren’t adequately investigated. These shaky housing loans were routinely bundled into investments known as “collateralized debt obligations” (or “CDOs”) and passed off as legitimate instruments when they were, in fact, seldom worth the paper they were printed on. In essence, the whole ball game was based on shoddy due diligence at best and rampant fraud at worst.

A handful of financial analysts saw the writing on the wall in 2005, and they projected a catastrophic collapse coming in 2007. Their thinking naturally ran contrary to the prevailing wisdom, and they were frequently laughed at by their peers. But they were undeterred in investigating matters further. Among those on this cutting-edge forefront was a colorful cast of characters:

* Michael Burry (Christian Bale), an eccentric, socially awkward, San Jose-based neurologist-turned-money manager with a penchant for heavy metal music and walking around barefoot. He astutely spotted the bubble when virtually no one else did and wanted to find a way to cash in on it. After all, if no one else was going to make money off of this impending disaster, at least he and his investors would. He proceeded to invent a financial instrument called a “credit default swap,” an investment that effectively bet against the viability of the risky loans, providing investors with a payout if they failed. The practice of purposely investing against the backers of the mortgages in hopes that the loans would default was known as “shorting.” At the time the swaps were created, buying into them was considered financial suicide. But, if Burry’s projections were to pan out, investors would be rewarded handsomely for their unconventional speculation.

* Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling), a slick, young, high-powered Wall Street banker who profited profusely from his efforts but who also had an underlying disdain for the conspicuous arrogance (and ignorance) of his colleagues. When he learned about Burry’s new investment vehicle, he looked into it and saw the financial opportunity of a lifetime emerging. He was determined to pounce on it, even if his clueless peers were oblivious to it, and sought investors to join him in this new venture.

* Mark Baum (Steve Carell), a high-strung hedge fund manager whose financial outlook was based on a wider view than just doing whatever it takes to make money. When approached by Vennett to join him in his bold undertaking, Baum was initially skeptical and decided to investigate further with the aid of his wise-cracking colleagues, Porter Collins (Hamish Linklater), Vinnie Daniel (Jeremy Strong) and Danny Moses (Rafe Spall). They quickly validated what Jared said, a revelation whose implications troubled Mark deeply, for he saw consequences far worse than anyone ever imagined – including those who spotted the emerging bubble in the first place.

* Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock), a pair of upstart Colorado-based money managers aching to break into the Wall Street financial world. They, too, spotted the coming mortgage market collapse and wanted in on the shorting transactions. But, because their operation amounted to financial small potatoes, they needed help to get into the game in a big way. They turned to their friend, Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt), a retired financier who now used his time and resources to promote socially conscious initiatives. Rickert possessed the clout to help Geller and Shipley – and the wits to take on a system that he had come to see as patently toxic.

Over time, the more these financial mavericks investigated the market, the more inherently corrupt they found it to be. When they discovered, for example, that some of the professionals charged with supposedly safeguarding the integrity of these investments (such as ratings agency analyst Georgia Hale (Melissa Leo) and CDO portfolio manager Mr. Chau (Byron Mann)) were blatantly disregarding their responsibilities, they were even more convinced that they were right. And, when they learned that no one in the media was willing to blow the whistle on the scam, they decided to jump in and await the arrival of their fortunes, for, if they were right about what was to transpire, the prospect of an untold fortune loomed large.

Betting on the mortgage market failing was seen as irresponsibly risky, something that most conventional financiers saw as a ludicrously improbable long shot—but one that would also yield an enormous payout if the projected result came to pass. Which it ultimately did.

The outcome of all this, of course, was the 2008 financial collapse. Even though it didn’t arrive exactly on cue, it arrived nevertheless, triggering a fiscal avalanche in short order (no pun intended). The fallout was felt far and wide; with the economy in meltdown, countless people lost their jobs and their homes. And, for what it’s worth, the prognosticators of financial doom made their money, their prescience in most cases tainted by decidedly mixed emotions. Sometimes being right doesn’t feel as good as one might assume it would.

Those who engage in the practice of conscious creation, the means by which we realize our reality through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents, should take heed of this cautionary tale. The narrative of “The Big Short” provides an exemplary example of what can happen when we blatantly disregard the forces that drive our existence.

For instance, while most of Wall Street was preoccupied with making money and having a good time without paying attention to how that was happening, a time bomb was lurking beneath the surface of the industry’s collective consciousness. By focusing purely on the result and ignoring how it came to pass, the financial industry effectively turned a blind eye to its own looming fate, a practice commonly known as un-conscious creation. And, by the time its ranks recognized what was happening, it was too late to do anything about it – both for themselves and the hordes of those affected by their intrinsic metaphysical irresponsibility.

The conscious creation component most notably lacking in this scenario was a vitally crucial element – integrity. When we seek to employ the process, we nearly always get the best results when we’re in touch with our beliefs, particularly those that reflect our truest selves. But, when such integrity is absent or shunted off to the side, the results rarely meet our hoped-for expectations. The financiers who put their own interests ahead of their work and the welfare of those they served clearly lacked this attribute in their beliefs. So, considering how events ultimately played out, is it any surprise that this shortcoming would come back to bite them in a big way? (Payback, it would seem, really can live up to its decidedly surly reputation.)

As with any conscious creation undertaking, this film thus capably illustrates how we get back what we put into our ventures, especially when we disregard the importance of elements like integrity. This obviously applies to the financial operatives who wound up broke; they lost their shirts when they lost their heads. But the same could also be said for the many homeowners who lost their properties when they agreed to loan deals that were effectively too good to be true. Their desire to own homes at all costs, no matter what it took, reflected their own lack of integrity – and their own practice of un-conscious creation.

By ignoring the importance of integrity in the conscious creation process, we’re playing with metaphysical fire. And, as the film aptly shows, it’s easy to get burned when we seek to manifest our existence without its presence in our belief portfolio.

By contrast, those who are true to themselves, who purposely include integrity as part of their mix of intentions, manage to see their goals realized. Having this quality in place enables such conscious creation practitioners to make better use of other metaphysical tools at their disposal, like intuition and the ability to spot synchronicities. This was very much the case with Burry, Vennett, Baum, Rickert and their associates. They saw the emerging scenario and listened to their instincts, even if no one else was willing to give the idea a second thought. And, when opportunities appeared that enabled them to capitalize on their well-considered hunches, they availed themselves of what they had to offer.

Given that the financiers in this film profited off of the hardship of others, one might legitimately ask, “Where’s the integrity in that?” That argument certainly has some merit. However, as “integrity” is used here, the term has to do with being true to oneself and one’s beliefs in seeing through the materialization of one’s reality. And, in that context, their beliefs were borne out. Indeed, they succeeded in being able to say to the naysayers, “I told you so.”

As for the moral implications of this, that’s an entirely different matter. As becomes apparent in the film, each of the protagonists had their own reactions to what they did and how they felt about it. Vennett, for example, saw the opportunity as a chance to cash in big and didn’t hesitate to do so, unaffected – and mostly unapologetic – about the fallout of having made his investment. That’s what he wanted for himself – and promptly proceeded to create it, plain and simple.

At the other end of the spectrum, Rickert, Baum and, to an extent, Burry saw what was happening in the financial industry before the collapse and were troubled by the implications, and their decisions to proceed with their investments were tempered by other considerations. Rickert, for instance, used his now-considerably enhanced financial resources to bankroll socially responsible endeavors, undertakings that may not have come into being as readily were it not for the funds he amassed through his investment.

Similarly, Baum and Burry realized they needed to look out for the welfare of their investors, and, even though they may not have been entirely comfortable with their actions, they were at least able to make the decisions necessary to take care of those who placed their faith in them. Time for soul searching of the greater implications involved came later, a process that was by no means easy for either of them. But, despite such introspection, they could rest assured that they did what they needed to do for their clients.

And then there were Geller and Shipley, who initially believed much as Vennett did. But, when Rickert pointed out the ramifications of what their investment would likely yield, they came in for a rude awakening. The experience proved to be a useful lesson in turning away from un-conscious creation toward a more considered outlook about their beliefs – and what they can produce.

The collectively created mass event that was the financial collapse consisted of a wide array of individual stories and life lessons. The circumstances that provided the means for these assorted experiences may have been jointly manifested, but that overarching scenario made it possible for a diverse range of people to obtain what they needed to get out of it. Given the stakes involved, we can only hope that we learned our lesson from it. The potential for loss from sleepwalking through life or approaching it without integrity is substantial, consequences that are likely to be worse each time we fail to pass the test.

“The Big Short” is a surprisingly enjoyable movie about an unlikely subject that’s brought to life through a clever script, understated wit and masterful film editing. The picture skillfully provides novel analogies to explain complex financial concepts, employing celebrity lecturers like Margot Robbie, Selena Gomez and Anthony Bourdain. But, most of all, the film features a superb cast with stellar performances by Bale, Carell, Gosling and Leo. I can honestly say this is my favorite film of 2015, outclassing virtually all of the other offerings from what turned out to be a somewhat tepid year in cinema.

This offering is well deserving of all the accolades it has received. It previously earned four Golden Globe Award nominations (best comedy picture, screenplay, and comedy actor honors (for Bale and Carell)), though it took home no statues. It subsequently won three Critics Choice Awards for best comedy, adapted screenplay and comedy actor (Bale) on seven total nominations. In pending competitions, the film is awaiting word on its two Screen Actors Guild Award nominations (best ensemble, supporting actor (Bale)), its four BAFTA nominations (best picture, editing, screenplay, supporting actor (Bale)) and its five Oscar nominations (best picture, director, adapted screenplay, editing, supporting actor (Bale)).

When we wonder why things turn out as they do, we need look no further than ourselves – and what drives us, namely, our beliefs. Sometimes we come up proud of ourselves, but, at other times, we might stumble upon some difficult realizations. This film illustrates that impeccably, showing us what can result when we grow lazy or unconcerned about the intents that create our existence. And that’s one instance where we certainly wouldn’t want to come up short.

Copyright © 2016, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

The Great Recession of 2008 is all too well known to a great many people. Much of the blame was placed on the collapse of the home mortgage market, and, at least superficially, that might be true. But what was behind that debacle, the underlying cause of an event that nearly brought the entire world’s economy to its knees? That’s what “The Big Short” seeks to explain.

In 2005, virtually everyone in the financial services industry was living high on the hog. Despite the losses that occurred in the wake of the 9/11 attacks, the economy rebounded strongly in the time since that fateful day in 2001. Money rolled in as if it were on a perpetual upward spiral, a nonstop gravy train that most insiders thought would never end. People in the business partied like there was no tomorrow, celebrating the good fortune that was now being looked on as unending and matter of fact.

Many of those fortunes were made in the home mortgage market, a segment of the economy seen as rock solid dependable. But was it? As several astute financial analysts began to discover, the mortgage business looked like a disaster waiting to happen. The “bubble” that was forming in the housing market was getting ready to burst – and in a very big way. But, because most everyone in the business was so busy swilling champagne and spending money hand over fist, no one was paying attention to the fact that the mortgage market was built on risky investments that weren’t adequately investigated. These shaky housing loans were routinely bundled into investments known as “collateralized debt obligations” (or “CDOs”) and passed off as legitimate instruments when they were, in fact, seldom worth the paper they were printed on. In essence, the whole ball game was based on shoddy due diligence at best and rampant fraud at worst.

A handful of financial analysts saw the writing on the wall in 2005, and they projected a catastrophic collapse coming in 2007. Their thinking naturally ran contrary to the prevailing wisdom, and they were frequently laughed at by their peers. But they were undeterred in investigating matters further. Among those on this cutting-edge forefront was a colorful cast of characters:

* Michael Burry (Christian Bale), an eccentric, socially awkward, San Jose-based neurologist-turned-money manager with a penchant for heavy metal music and walking around barefoot. He astutely spotted the bubble when virtually no one else did and wanted to find a way to cash in on it. After all, if no one else was going to make money off of this impending disaster, at least he and his investors would. He proceeded to invent a financial instrument called a “credit default swap,” an investment that effectively bet against the viability of the risky loans, providing investors with a payout if they failed. The practice of purposely investing against the backers of the mortgages in hopes that the loans would default was known as “shorting.” At the time the swaps were created, buying into them was considered financial suicide. But, if Burry’s projections were to pan out, investors would be rewarded handsomely for their unconventional speculation.

* Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling), a slick, young, high-powered Wall Street banker who profited profusely from his efforts but who also had an underlying disdain for the conspicuous arrogance (and ignorance) of his colleagues. When he learned about Burry’s new investment vehicle, he looked into it and saw the financial opportunity of a lifetime emerging. He was determined to pounce on it, even if his clueless peers were oblivious to it, and sought investors to join him in this new venture.

* Mark Baum (Steve Carell), a high-strung hedge fund manager whose financial outlook was based on a wider view than just doing whatever it takes to make money. When approached by Vennett to join him in his bold undertaking, Baum was initially skeptical and decided to investigate further with the aid of his wise-cracking colleagues, Porter Collins (Hamish Linklater), Vinnie Daniel (Jeremy Strong) and Danny Moses (Rafe Spall). They quickly validated what Jared said, a revelation whose implications troubled Mark deeply, for he saw consequences far worse than anyone ever imagined – including those who spotted the emerging bubble in the first place.

* Charlie Geller (John Magaro) and Jamie Shipley (Finn Wittrock), a pair of upstart Colorado-based money managers aching to break into the Wall Street financial world. They, too, spotted the coming mortgage market collapse and wanted in on the shorting transactions. But, because their operation amounted to financial small potatoes, they needed help to get into the game in a big way. They turned to their friend, Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt), a retired financier who now used his time and resources to promote socially conscious initiatives. Rickert possessed the clout to help Geller and Shipley – and the wits to take on a system that he had come to see as patently toxic.

Over time, the more these financial mavericks investigated the market, the more inherently corrupt they found it to be. When they discovered, for example, that some of the professionals charged with supposedly safeguarding the integrity of these investments (such as ratings agency analyst Georgia Hale (Melissa Leo) and CDO portfolio manager Mr. Chau (Byron Mann)) were blatantly disregarding their responsibilities, they were even more convinced that they were right. And, when they learned that no one in the media was willing to blow the whistle on the scam, they decided to jump in and await the arrival of their fortunes, for, if they were right about what was to transpire, the prospect of an untold fortune loomed large.

Betting on the mortgage market failing was seen as irresponsibly risky, something that most conventional financiers saw as a ludicrously improbable long shot—but one that would also yield an enormous payout if the projected result came to pass. Which it ultimately did.

The outcome of all this, of course, was the 2008 financial collapse. Even though it didn’t arrive exactly on cue, it arrived nevertheless, triggering a fiscal avalanche in short order (no pun intended). The fallout was felt far and wide; with the economy in meltdown, countless people lost their jobs and their homes. And, for what it’s worth, the prognosticators of financial doom made their money, their prescience in most cases tainted by decidedly mixed emotions. Sometimes being right doesn’t feel as good as one might assume it would.

Those who engage in the practice of conscious creation, the means by which we realize our reality through the power of our thoughts, beliefs and intents, should take heed of this cautionary tale. The narrative of “The Big Short” provides an exemplary example of what can happen when we blatantly disregard the forces that drive our existence.

For instance, while most of Wall Street was preoccupied with making money and having a good time without paying attention to how that was happening, a time bomb was lurking beneath the surface of the industry’s collective consciousness. By focusing purely on the result and ignoring how it came to pass, the financial industry effectively turned a blind eye to its own looming fate, a practice commonly known as un-conscious creation. And, by the time its ranks recognized what was happening, it was too late to do anything about it – both for themselves and the hordes of those affected by their intrinsic metaphysical irresponsibility.

The conscious creation component most notably lacking in this scenario was a vitally crucial element – integrity. When we seek to employ the process, we nearly always get the best results when we’re in touch with our beliefs, particularly those that reflect our truest selves. But, when such integrity is absent or shunted off to the side, the results rarely meet our hoped-for expectations. The financiers who put their own interests ahead of their work and the welfare of those they served clearly lacked this attribute in their beliefs. So, considering how events ultimately played out, is it any surprise that this shortcoming would come back to bite them in a big way? (Payback, it would seem, really can live up to its decidedly surly reputation.)

As with any conscious creation undertaking, this film thus capably illustrates how we get back what we put into our ventures, especially when we disregard the importance of elements like integrity. This obviously applies to the financial operatives who wound up broke; they lost their shirts when they lost their heads. But the same could also be said for the many homeowners who lost their properties when they agreed to loan deals that were effectively too good to be true. Their desire to own homes at all costs, no matter what it took, reflected their own lack of integrity – and their own practice of un-conscious creation.

By ignoring the importance of integrity in the conscious creation process, we’re playing with metaphysical fire. And, as the film aptly shows, it’s easy to get burned when we seek to manifest our existence without its presence in our belief portfolio.

By contrast, those who are true to themselves, who purposely include integrity as part of their mix of intentions, manage to see their goals realized. Having this quality in place enables such conscious creation practitioners to make better use of other metaphysical tools at their disposal, like intuition and the ability to spot synchronicities. This was very much the case with Burry, Vennett, Baum, Rickert and their associates. They saw the emerging scenario and listened to their instincts, even if no one else was willing to give the idea a second thought. And, when opportunities appeared that enabled them to capitalize on their well-considered hunches, they availed themselves of what they had to offer.

Given that the financiers in this film profited off of the hardship of others, one might legitimately ask, “Where’s the integrity in that?” That argument certainly has some merit. However, as “integrity” is used here, the term has to do with being true to oneself and one’s beliefs in seeing through the materialization of one’s reality. And, in that context, their beliefs were borne out. Indeed, they succeeded in being able to say to the naysayers, “I told you so.”

As for the moral implications of this, that’s an entirely different matter. As becomes apparent in the film, each of the protagonists had their own reactions to what they did and how they felt about it. Vennett, for example, saw the opportunity as a chance to cash in big and didn’t hesitate to do so, unaffected – and mostly unapologetic – about the fallout of having made his investment. That’s what he wanted for himself – and promptly proceeded to create it, plain and simple.

At the other end of the spectrum, Rickert, Baum and, to an extent, Burry saw what was happening in the financial industry before the collapse and were troubled by the implications, and their decisions to proceed with their investments were tempered by other considerations. Rickert, for instance, used his now-considerably enhanced financial resources to bankroll socially responsible endeavors, undertakings that may not have come into being as readily were it not for the funds he amassed through his investment.

Similarly, Baum and Burry realized they needed to look out for the welfare of their investors, and, even though they may not have been entirely comfortable with their actions, they were at least able to make the decisions necessary to take care of those who placed their faith in them. Time for soul searching of the greater implications involved came later, a process that was by no means easy for either of them. But, despite such introspection, they could rest assured that they did what they needed to do for their clients.

And then there were Geller and Shipley, who initially believed much as Vennett did. But, when Rickert pointed out the ramifications of what their investment would likely yield, they came in for a rude awakening. The experience proved to be a useful lesson in turning away from un-conscious creation toward a more considered outlook about their beliefs – and what they can produce.

The collectively created mass event that was the financial collapse consisted of a wide array of individual stories and life lessons. The circumstances that provided the means for these assorted experiences may have been jointly manifested, but that overarching scenario made it possible for a diverse range of people to obtain what they needed to get out of it. Given the stakes involved, we can only hope that we learned our lesson from it. The potential for loss from sleepwalking through life or approaching it without integrity is substantial, consequences that are likely to be worse each time we fail to pass the test.

“The Big Short” is a surprisingly enjoyable movie about an unlikely subject that’s brought to life through a clever script, understated wit and masterful film editing. The picture skillfully provides novel analogies to explain complex financial concepts, employing celebrity lecturers like Margot Robbie, Selena Gomez and Anthony Bourdain. But, most of all, the film features a superb cast with stellar performances by Bale, Carell, Gosling and Leo. I can honestly say this is my favorite film of 2015, outclassing virtually all of the other offerings from what turned out to be a somewhat tepid year in cinema.

This offering is well deserving of all the accolades it has received. It previously earned four Golden Globe Award nominations (best comedy picture, screenplay, and comedy actor honors (for Bale and Carell)), though it took home no statues. It subsequently won three Critics Choice Awards for best comedy, adapted screenplay and comedy actor (Bale) on seven total nominations. In pending competitions, the film is awaiting word on its two Screen Actors Guild Award nominations (best ensemble, supporting actor (Bale)), its four BAFTA nominations (best picture, editing, screenplay, supporting actor (Bale)) and its five Oscar nominations (best picture, director, adapted screenplay, editing, supporting actor (Bale)).

When we wonder why things turn out as they do, we need look no further than ourselves – and what drives us, namely, our beliefs. Sometimes we come up proud of ourselves, but, at other times, we might stumble upon some difficult realizations. This film illustrates that impeccably, showing us what can result when we grow lazy or unconcerned about the intents that create our existence. And that’s one instance where we certainly wouldn’t want to come up short.

Copyright © 2016, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

Published on January 21, 2016 11:17

January 16, 2016

‘Hitchcock/Truffaut’ chronicles creative mastery at work

“Hitchcock/Truffaut” (2015). Cast: Interviews: Martin Scorsese, David Fincher, Arnaud Desplechin, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Wes Anderson, James Gray, Olivier Assayas, Richard Linklater, Peter Bogdanovich, Paul Schrader, Mathieu Amalric (narrator). Archive Footage: Alfred Hitchcock, François Truffaut, James Stewart, Henry Fonda, Cary Grant, Anthony Perkins, Martin Balsam, Kim Novak, Tippi Hendren, Janet Leigh, Vera Miles, Doris Day, Veronica Cartwright, Rod Taylor, Jessica Tandy, Montgomery Clift, Alma Reville. Director: Kent Jones. Screenplay: Kent Jones and Serge Toubiana. Book: François Truffaut, Hitchcock/Truffaut (originally released as Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock (The Cinema According to Alfred Hitchcock)). Web site. Trailer.

The creative mind is something to behold. How it functions in realizing its goals is mesmerizing and, for many of us, mysterious. But understanding its workings need not be quite so inscrutable if we look at what drives it, the beliefs that emerge from our consciousness and that mobilize themselves for the materialization of the visions held within them. An examination of how this plays out as illustrated through the works of two legendary artists provides the focus of the compelling new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.”

In 1962, filmmaker François Truffaut (1932-1984) was a rising star in the world of cinema, having directed a small but significant number of acclaimed pictures, such as “The 400 Blows” (1959) and “Jules and Jim” (1962). Yet, when the brash young French auteur was asked to name the greatest influence on his work, he cited a veteran of the field, someone many years his senior, the legendary British director Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980).

As the visionary who brought to life such pictures as “Vertigo” (1958), “The Birds” (1963), “Psycho” (1960), “North by Northwest” (1959) and “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934 and 1956), Hitchcock created a singular style of filmmaking and transformed the medium in countless ways, influencing legions of young directors like Truffaut. But exactly how did Hitchcock achieve this?

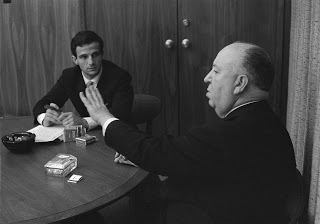

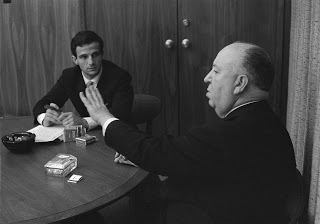

That’s what Truffaut wanted to find out. He contacted Hitchcock and asked him if he would be willing to sit with him for a week-long series of interviews to share his secrets of filmmaking, a request to which the master agreed. Based on the dialogues that came out of that meeting, Truffaut penned a book that would become must-reading for aspiring filmmakers, Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock (The Cinema According to Alfred Hitchcock) (later rereleased as Hitchcock/Truffaut). That seminal work, in turn, provided the inspiration for this documentary.

The story of this historic summit is fleshed out through excerpts from the original interview tape recordings, backed by still images of the meeting snapped by veteran portrait photographer Philippe Halsman (1906-1979). Intercut with this material is a choice selection of archive footage from the films of Hitchcock and Truffaut, particularly clips that epitomize the principles characteristic of their work. And all of this is further put into perspective by the insights of many of today’s leading directors, including filmmakers Martin Scorsese (“Taxi Driver” (1976), “Hugo” (2011)), David Fincher (“The Social Network” (2010), “Gone Girl” (2014)), Wes Anderson (“Moonrise Kingdom” (2012), “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014)), Richard Linklater (“Boyhood” (2014), “Waking Life” (2001)), Peter Bogdanovich (“The Last Picture Show” (1971), “Paper Moon” (1973)) and Paul Schrader (“Auto Focus” (2002), “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” (1985)).

In his younger days, French filmmaker François Truffaut (left) was so enamored by the works of veteran director Alfred Hitchcock (right) that he set up a week-long meeting with him purely to discuss the secrets of cinema success, a summit now chronicled in the new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” Photo by Philippe Halsman, courtesy of Cohen Media Group.

In his younger days, French filmmaker François Truffaut (left) was so enamored by the works of veteran director Alfred Hitchcock (right) that he set up a week-long meeting with him purely to discuss the secrets of cinema success, a summit now chronicled in the new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” Photo by Philippe Halsman, courtesy of Cohen Media Group.

Even though the film’s title contains the names of both directors, the picture focuses more on Hitchcock than Truffaut, primarily because the master’s output far exceeded his protégé’s, both at the time of their meeting and over the course of their respective careers. Despite this disparity, however, the film nevertheless examines the works and philosophies of both directors using the aforementioned combination of elements, providing viewers with an interesting exploration of what made each artist’s works come to life. This is particularly true when it comes to the beliefs and perspectives that drove them and led to the materialization of their finished products. In this way, then, viewers are treated to a highly illustrative case study into the workings of the conscious creation process, the means by which our reality and all of its component parts (including those of an artistic nature) come into being.

For instance, the film details how Hitchcock made use of conscious creation principles to inventively explore themes like sexuality and obsession in his movies, many of which are depicted symbolically yet effectively. This is perhaps most obvious in “Vertigo” in which Hitchcock had to get creative to convey these provocative ideas despite the puritanical standards in place at the time the film was made. To make these points, he had to believe that they could be successfully expressed without being hemmed in by prevailing moral and industry limitations, a challenge that prompted him to search the boundless realm of possibilities to find ways to fulfill his goals. That search, of course, ultimately led to some of the most suggestive imagery ever captured on film – and all without sacrificing his obligation to conform to the socially acceptable norms of the era.

Similarly, this is also how Hitchcock helped transform the way we look at film. Before the director made a name for himself in the 1940s and ʼ50s, movies were largely seen as an amusing diversion, a lightweight commercial pastime. However, through the use of his many cinematic innovations, Hitchcock elevated a form of popular entertainment into a form of art, taking it to heights of serious aesthetic consideration never before seen. He would subsequently blaze a similar trail for how movies were financed and distributed, a revolutionary accomplishment detailed in the biopic “Hitchcock” (2012), a chronicle detailing how his classic screamfest “Psycho” came into being.

Both of the foregoing examples illustrate how conscious creation can prove invaluable for resolving challenges of any kind, be they artistic or otherwise. By embracing the perspective that limitless options for expression are always available to us at any given moment – regardless of the context involved – we enable ourselves to drum up workable solutions, as Hitchcock’s ingenuity illustrates. (Bear this in mind the next time you believe something insurmountable crosses your path.)

The experiences one encounters in one part of life often have impact on others, as is apparent in the films of both directors. For example, events from Truffaut’s childhood provided fodder for the lives of his characters as seen in works like “The 400 Blows” and “Day for Night” (1973). The events that manifested in his youth had a subsequent bleed-through effect in his later artistic life, enlivening his characters in ways that paralleled his own experiences. The beliefs that led to the realization of those initial circumstances thus served to inspire those yet to come, and, even though those latter materializations occurred in a fictional context, they nevertheless mirrored their forerunners, springing forth in both cases from the consciously creative mind of the same individual.

The same could be said of Hitchcock’s infamous personal preoccupation with blonde femme fatales. So, given that, is it any wonder that he ended up casting actresses who emulated those qualities for his films? Again, the attributes of one milieu carried over into another.

In both of the foregoing examples, the parallels between the life and artistic experiences of the two directors illustrate another of conscious creation’s cornerstone principles, the connectedness of all things. Much of the time, many of us tend to view our existence from a compartmentalized standpoint, looking upon all of the elements of our lives as separate, individualized components. Yet, when we consider how conscious creation functions and see how comparable notions recur in different aspects of our reality, we’re invariably able to trace the roots in each case to a common source, our beliefs (and, frequently, analogous beliefs at that). This thus helps to explain why the underlying themes present in one area of life mimic those found in others.

Two giants of cinema, François Truffaut (left) and Alfred Hitchcock (right), meet for a historic summit on moviemaking in 1962, the subject of Kent Jones’s new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” Photo by Philippe Halsman, courtesy of Cohen Media Group.

Two giants of cinema, François Truffaut (left) and Alfred Hitchcock (right), meet for a historic summit on moviemaking in 1962, the subject of Kent Jones’s new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” Photo by Philippe Halsman, courtesy of Cohen Media Group.

Anyone who appreciates the power of conscious creation concepts, the influential impact of cinema and how these elements overlap with one another (the basis upon which I view and analyze film, not to mention the underlying foundation of my writing) is likely to see the value of “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” This documentary capably illustrates these notions not only in principle, but also through the specific works and experiences of two of the art form’s greatest practitioners. Audiences can thus take away much from viewing this inspirational and enlightening offering, all the while having an enjoyable time at the movies. To be sure, the film would have benefited from paying a little more attention to Truffaut’s repertoire, but, this shortcoming aside, this release is solid in virtually every other respect.

This nominee for the 2015 Cannes Film Festival Golden Eye documentary award is a must-see for die-hard cinephiles. It’s currently playing in limited release in theaters specializing in documentary, independent and foreign films.

The compulsion to create, and the desire to become a master at it, is something all great artists strive for. It can be seen in their work and in the vision they hold to see those creations come to life. Alfred Hitchcock and François Truffaut personified those notions, resplendently inspiring the generations of filmmakers – and conscious creators – who followed them.

Copyright © 2016, by Brent Marchant. All rights reserved.

The creative mind is something to behold. How it functions in realizing its goals is mesmerizing and, for many of us, mysterious. But understanding its workings need not be quite so inscrutable if we look at what drives it, the beliefs that emerge from our consciousness and that mobilize themselves for the materialization of the visions held within them. An examination of how this plays out as illustrated through the works of two legendary artists provides the focus of the compelling new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.”

In 1962, filmmaker François Truffaut (1932-1984) was a rising star in the world of cinema, having directed a small but significant number of acclaimed pictures, such as “The 400 Blows” (1959) and “Jules and Jim” (1962). Yet, when the brash young French auteur was asked to name the greatest influence on his work, he cited a veteran of the field, someone many years his senior, the legendary British director Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980).

As the visionary who brought to life such pictures as “Vertigo” (1958), “The Birds” (1963), “Psycho” (1960), “North by Northwest” (1959) and “The Man Who Knew Too Much” (1934 and 1956), Hitchcock created a singular style of filmmaking and transformed the medium in countless ways, influencing legions of young directors like Truffaut. But exactly how did Hitchcock achieve this?

That’s what Truffaut wanted to find out. He contacted Hitchcock and asked him if he would be willing to sit with him for a week-long series of interviews to share his secrets of filmmaking, a request to which the master agreed. Based on the dialogues that came out of that meeting, Truffaut penned a book that would become must-reading for aspiring filmmakers, Le Cinéma selon Alfred Hitchcock (The Cinema According to Alfred Hitchcock) (later rereleased as Hitchcock/Truffaut). That seminal work, in turn, provided the inspiration for this documentary.

The story of this historic summit is fleshed out through excerpts from the original interview tape recordings, backed by still images of the meeting snapped by veteran portrait photographer Philippe Halsman (1906-1979). Intercut with this material is a choice selection of archive footage from the films of Hitchcock and Truffaut, particularly clips that epitomize the principles characteristic of their work. And all of this is further put into perspective by the insights of many of today’s leading directors, including filmmakers Martin Scorsese (“Taxi Driver” (1976), “Hugo” (2011)), David Fincher (“The Social Network” (2010), “Gone Girl” (2014)), Wes Anderson (“Moonrise Kingdom” (2012), “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014)), Richard Linklater (“Boyhood” (2014), “Waking Life” (2001)), Peter Bogdanovich (“The Last Picture Show” (1971), “Paper Moon” (1973)) and Paul Schrader (“Auto Focus” (2002), “Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters” (1985)).

In his younger days, French filmmaker François Truffaut (left) was so enamored by the works of veteran director Alfred Hitchcock (right) that he set up a week-long meeting with him purely to discuss the secrets of cinema success, a summit now chronicled in the new documentary, “Hitchcock/Truffaut.” Photo by Philippe Halsman, courtesy of Cohen Media Group.