Linda Rodriguez's Blog, page 6

September 8, 2016

An Old, Old Story—Dealing Illegally and in Bad Faith with America's Indigenous People

Near the Cannonball River in North Dakota just outside the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, over 3,000 people are gathered from Indigenous nations all over the United States to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (a kind of stealth or back-door Keystone XL Pipeline approved under a “fast track” option that didn't require the scrutiny Keystone had undergone) from destroying tribal burial grounds and sacred sites and from crossing the Missouri River, endangering the source of drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and for millions of other Americans downstream.

Near the Cannonball River in North Dakota just outside the Standing Rock Sioux reservation, over 3,000 people are gathered from Indigenous nations all over the United States to stop the Dakota Access Pipeline (a kind of stealth or back-door Keystone XL Pipeline approved under a “fast track” option that didn't require the scrutiny Keystone had undergone) from destroying tribal burial grounds and sacred sites and from crossing the Missouri River, endangering the source of drinking water for the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and for millions of other Americans downstream.The land the pipeline is scheduled to cross is ancestral land of the Standing Rock Sioux, taken from them in the 20th century in violation of U.S. treaties with the Standing Rock nation. When they went to federal court in 1980 over this and other land depredations, the judge said, “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history.” President Obama, when questioned about the DAPL situation at a university in Laos this week, said, “...the way that Native Americans were treated was tragic. … This issue of ancestral lands and helping them preserve their way of life is something that we have worked very hard on.” He did not, unfortunately, answer the question he was asked about the situation of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

The elders, who are the leaders of the Standing Stone camp in resistance to the DAPL (as is customary among most Native nations), issued this statement:

“With over 200 river crossings the proposed Dakota Access Pipeline puts the drinking water supply of a large part of the country at risk. Our prayer is to keep the waters pure for all tribal peoples and all Americans.

We pray for the waters used by farmers in Iowa and Illinois, the water consumed by schoolchildren in South Dakota, Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

Millions of Americans get their drinking water from this system.

We are Protectors not Protesters. Our camp is a prayer, for our children, our elders and ancestors, and for the creatures, and the land and habitat they depend on, who cannot speak for themselves.

We wish the Army Corps had done their job in protecting federally administered lands, unceded Indian lands, and Tribal lands, relying on science and judgement in protecting Indian culture from construction. Whether by intention or omission, the Army Corps broke federal laws, and didn’t do their job.”

The pipeline was originally slated to run past Bismarck, North Dakota, at a distance of 15 miles from the city, but there was outcry that the state capitol's drinking water might be endangered by a leak or break in the 1,100-mile pipeline. Thus, it was shifted to run within half a mile of the Standing Rock reservation. As Dave Archambault II, the chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation, told CNN, whenever the United States wants to make sacrifices for economic purposes, it tends to do so on the backs of its Indigenous people, and this longstanding history of economic decision-making at the expense of Natives must stop.

After a federal court injunction to stop construction until the matter could be litigated and the day after the tribe's lawyers filed additional papers in court with information of sacred sites and burial sites along the pipeline path, DAPL sent work crews on a holiday weekend with three bulldozers to dig up those sites and destroy them in order to make them irrelevant to the case. As the gathered Natives tried to block them from digging up and destroying their relatives' graves, a private security company hired by DAPL blocked all cell phone reception to keep word from getting out and then assaulted them with pepper spray and attack dogs. Several protesters were bitten, including a pregnant woman, and one was hospitalized with facial dog bites. Amy Goodman and Democracy Now were in the camp interviewing its members and caught the entire event on camera (see link below), including dogs with bloody mouths after biting Natives, which is probably the only reason the security guards finally left and didn't cause even more injuries. It becomes apparent from this and from the sheriff's statement afterward that the camp attacked the security guards and dogs, injuring them, (when the sheriff was not on the scene at the time) that neither DAPL nor the local authorities are dealing in good faith or legality.

After a federal court injunction to stop construction until the matter could be litigated and the day after the tribe's lawyers filed additional papers in court with information of sacred sites and burial sites along the pipeline path, DAPL sent work crews on a holiday weekend with three bulldozers to dig up those sites and destroy them in order to make them irrelevant to the case. As the gathered Natives tried to block them from digging up and destroying their relatives' graves, a private security company hired by DAPL blocked all cell phone reception to keep word from getting out and then assaulted them with pepper spray and attack dogs. Several protesters were bitten, including a pregnant woman, and one was hospitalized with facial dog bites. Amy Goodman and Democracy Now were in the camp interviewing its members and caught the entire event on camera (see link below), including dogs with bloody mouths after biting Natives, which is probably the only reason the security guards finally left and didn't cause even more injuries. It becomes apparent from this and from the sheriff's statement afterward that the camp attacked the security guards and dogs, injuring them, (when the sheriff was not on the scene at the time) that neither DAPL nor the local authorities are dealing in good faith or legality.http://www.democracynow.org/2016/9/4/dakota_access_pipeline_company_attacks_native

This is national news of great importance, but until the past two days, this defense of sacred lands and waters, which has lasted for months, was paid no attention by the national news media, although multiple major international media outlets stayed on top of it and broadcast/wrote about it for their audiences around the world. It's an old, old story, however—U.S. government and private corporations deal in bad faith and illegally with Indigenous nations. Genocide, ethnic cleansing, land theft, you name it—this treatment of its Indigenous people by a country that claims to be a shining city of virtue and fairness on a hill above all others as an example to the world is, with slavery and its modern results, as well, hiding dark, shameful roots.

When racist trolls at public events and online tell us to “get over it,” this is why we can't. It's still going on, still happening to our people—even today when Americans say, “That was our ancestors, not us. We would never do that.” To all those Americans, I say this, “If you allow this corporation and your government to do this today, you are still doing what your ancestors did to the Indigenous people whose land you live on and work on today.”

Published on September 08, 2016 08:56

September 1, 2016

An Essay about the Last Time Demagogues Forcibly Deported Masses of Mexican-Americans

After listening to the horrible fascist talk by the Republican presidential candidate last night, I decided to post this essay I wrote about Latinos in the Midwest and about the last time we did this forced mass deportation/ethnic cleansing thing.

We’ve Been Here All Along: 13 Ways of Looking at Latinos in the Midwest

by Linda Rodriguez

1.

I listen for the broken truth that speaks of what’s been stolen, what’s been cracked and smashed. Bit by bit, I try to put together pieces, fragments of what was, stories for my children to live on. I refuse the blindness and forgetfulness that would render me acceptable in my country’s eyes, this country that lies about what it did to its indigenous roots, about who provides the necessary labor for all the luxury in which we live. Our comfortable lives are built on bones, and how we long to forget!2.

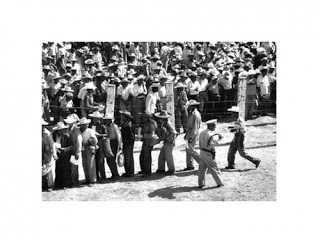

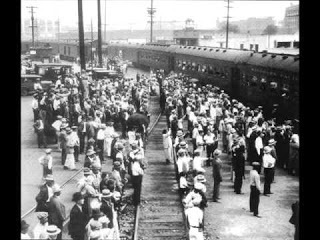

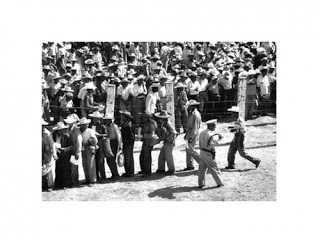

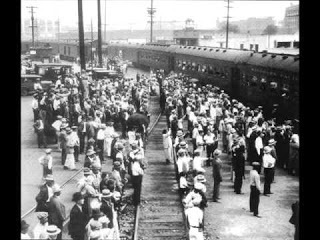

Here in the middle of the country’s heart, I live surrounded by the liquid names I love—Arredondo, Villalobos, Siquieros, Duarte, Espinoza. We are a secret pool in the middle of this dry, often drought-cursed Bible Belt, petitioners of La Virgen de Guadalupe and Tonantzin with tall flickering novena candles set out on household altars, devourers of caldo, horchata, albondigas with tongues that roll “r”s and hiss our “z”s, dark faces, eyes, hair among all these pale ones.How did we come to be here in a land covered in ice half the year? How did we come to this place where no parrots fly free and flowers freeze to death? Surely it was not our doing.3.Though larger totals of Latinos were driven out of the border states during the Depression’s forced deportations, the usually isolated communities in the Midwest were hit the hardest—in some cases, losing over half their population overnight. Those remaining kept their heads down, hoping to avoid another violent outbreak. They made their children speak only English.Though that had not mattered. Many of those shipped to Mexico were citizens who spoke English fluently and little, if any, Spanish.The Midwestern communities became even more invisible. They just wanted to be left alone.4.When Federales chased Pancho Villa and his soldados over the countryside in and out of the small farms and ranches and the dusty little towns that supported them, each side of the conflict when it stopped for a rest would force all the men and boys in a village or on a farm to join its army. Worn out from the constant warfare of Mexico of that time, those men and boys—and their families—wanted to be left in peace. They fled to cities where men in suits from the north offered them money if they would migrate to the land of gringos to work on railroads or in meatpacking plants. The old streets-of-gold promise, and it sounded much better than getting shot in one army or another. Taking their families, they moved north to Chicago, Kansas City, and Topeka.5.Ironically, when the U.S. entered World War II and needed cannon fodder, politicians remembered those English-speaking, American-citizen kids that they'd forced from their own country. They sent military recruiters south. Large numbers of boys, driven by force from their country to a land where they didn’t speak the language and never fit in, signed up to go to Europe and the Pacific to fight for the country they loved—even if it didn’t love them.If you didn’t read about this in your school history books, don’t be surprised. Neither did I. This whole episode was like the internment of American citizens of Japanese descent in camps during World War II. After the paroxysm was over, we as a nation only wanted to forget what we had done.6.The oldest Latino community in Kansas City, Kansas, was built around an entire village removed from Michoacan and settled into broken-down boxcars beside the Kaw River. When I was younger, you could still see the boxcar origins of a few houses in the Oakland community of Topeka, Kansas, and the Argentine district in Kansas City, Kansas. Around the core of boxcar, wood siding was added. New rooms and additions were built over the years to make real homes.Few of these houses have survived the past four decades, but I still remember them, always surrounded with luxuriant vegetable and flower gardens in the tiny yard space around the houses—an emphatic statement of a people who could indeed make silk purses out of sows’ ears or real two- or three-bedroom homes out of broken-down boxcars.7.In 2007, Kansas City, Missouri, had a new mayor. He had just appointed a very active member of the local Minutemen organization to Kansas City’s most powerful board. I found the local Minutemen chapter’s website and read a call to go door-to-door in Kansas City, demanding to see proof of citizenship or legal status and making “citizen’s arrests” where the occupant could not or would not show these. It was clear from the rhetoric on the website that these would not be random visits but would target homes with occupants who had Spanish last names.I took this threat personally. So when my friend Freda asked me to come to an emergency press conference to show solidarity, I did. Leaders of Chicano/Latino civic organizations formed the Kansas City Latino Civil Rights Task Force to fight this appointment. We were sure this would all end quickly. We were wrong, of course. It took over six months of constant effort, national groups cancelling conventions in the city, and the cooperation of African American, Jewish, and Anglo groups.

Along the way, something happened that I have still to forget.After one meeting, my friend Tino of LULAC emailed me, “This is what the Minutemen want.” Attached was a documentary video. The black and white photos of Latino families being forced into crowded boxcars reminded me powerfully of similar photos of Jewish families being loaded onto trains in Nazi-occupied areas of Europe during the same years.8.When the Great Depression hit, citizens of Mexican ancestry made a great scapegoat. Demagogues, sounding much like people we hear over the airwaves today, blamed them and called for mass deportations. Groups of armed vigilantes, most supported by local, state, and federal government, beat and kidnapped men walking down the street to work or home, visited homes with threats of violence and arrest, and drove families out without any of their possessions. They forced huge numbers of people without any of their belongings or food or water into railroad boxcars where the doors were locked shut and the people eventually dumped out in Mexico. The elderly, babies and pregnant women, those already sick—physically or mentally—suffered the most, and many died along the way. Twenty-five children and adults died on just one of these trains on its trip to the border.9.When my children were small, I would take them with me to the Westside, to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, where the grandmothers sold fresh tamales every Saturday to support the church. We would enter the cool basement where las Guadalupeñas would coo at Crystal and Niles en español. Crystal would respond by dancing around and laughing. Niles would try to hide his face in my pant legs, clinging tightly and crying until he pressed new creases. The old women would pack the still-steaming tamales, wrapped by the dozens in foil, into a paper bag and call out goodbyes to el niñito timido.On the way to the car, I would promise if he stopped crying we would visit La Fama, the panadería, for Mexican bread. We picked out thick, sugary cookie flags and pan dulce, carrying them all in a paper bag that began to show grease spots from the sweet treats inside before we got home.Or perhaps I would hold out the prospect of a visit to Sanchez Market for chicharrones, the real thing, large, bubbled, almost transparent from the deep-frying that made them so light and crunchy. While there, I would stock up on peppers and spices that couldn’t be found anywhere else in town as the kids relished their big chunks of fried pork rind.Back then, we gathered around the church and food—at weddings, after funerals, for quinceañeras, after First Communions, and at fundraisers for American GI Forum, the organization founded by decorated, returning Latino World War II veteranos when the American Legion wouldn’t allow them to join.Many women had a specialty food—tamales, enchiladas, mole, tostadas, arroz con pollo, sopa—that they were asked to bring. You always wanted to go if they had Lupe’s mole or Jennie’s enchiladas. They were better than you could get anywhere else unless you were lucky enough to belong to Lupe’s or Jennie’s family. But these women were generous and always shared with other families who were celebrating or mourning or just raising money for beloved causes.10.Many of those driven out in the 1930s were legal residents or citizens, naturalized and native-born. Children born and raised in this country were forced into a country they did not know with a language they did not know and often compelled to leave behind the birth certificates that proved their citizenship. Sixty percent of the 1.2 million people driven out of the country were citizens. Many of these families who were marched to the railroad cars and shipped out like so much freight owned their own homes and even had small businesses. All of this was forfeited to the mobs that kidnapped them and sent them out of the U.S.11.Herbert Hoover never made a formal policy of forced deportation, but elements within his government, along with state and local governments, arranged for the railroad cars and gave approval to the vigilantes. In some cases, it was actually government agents who drove people out of their homes. At times, private institutions also financed deportation boxcars. For example, the archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, paid for boxcars to take families out of the city, many of whom had lived there and worshipped as faithful Catholics since before the turn of the century. In fact, in southern California, hundreds of families were rounded up in 1931 as they attended Catholic services on Ash Wednesday.12.In Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, we have a large Chicano population that has been in the area since the turn of the twentieth century with third-generation and fourth-generation adult U.S. citizens who speak primarily (and often only) English, have college educations, and work as professionals. We also have a large, newer population, deriving from Central and South America as much as from Mexico, as often as not completely indigenous with little or no Spanish, speaking Nahuatl, Quechua, Q'eqchi'.I have often thought the great public horror evinced about this new wave of immigrants is due to their indigenous nature. The United States can hardly bear to see such large numbers of indigenous people as anything but threat when this country has worked so long and so hard at wiping out its own indigenous peoples through violence, disease, “education,” and the blood quantum rule the BIA has imposed on our indigenous nations that still endure.In 2007, my son Niles took a one-week European vacation. He flew home from London by way of Detroit. In Detroit, this non-Spanish-speaking, second-generation American citizen (on his father’s side), born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, was held for 24 hours by immigration authorities and refused entry into his own country, even though he had a passport. They were certain he was an illegal immigrant from Mexico trying to sneak into the U.S.Neither his valid documents nor his non-accented, perfectly colloquial English could outweigh his brown skin and Spanish last name. He was released and allowed to enter his own country only after his white boss confirmed over the telephone that he was a citizen and had been gainfully employed in a high-level professional position for seven years.To me, this is doubly galling because Niles is not only Chicano but also part Cherokee and part Choctaw. My children and I have several lines of ancestors who go back to the time before there was a United States of America. I have always since wondered just exactly how many illegal immigrants from Mexico named Niles have flown to England and toured the Continent before trying to sneak into the U.S. on a flight from London.13.People always are surprised to find Latinos in Kansas City—anywhere in the Midwest. We’re only supposed to congregate in Miami, New York, El Paso, Phoenix, and LA.Sometimes I want to ask, “Who did you think picked all those fruits and vegetables from the breadbasket of the country? Who worked in the meatpacking hellholes, if not the Mexicans and Indians? Who kept the trains cleaned, painted, and running, if not the African Americans and Mexicans?”Always the invisible poor, laborers doing the work no one else wanted. Now, it’s roofing and gardening, cleaning hotel rooms and offices at night. We’ve been here a long time, long enough to lose our language sometimes while we were gaining diplomas and degrees, but never to lose our culture completely. The newcomers make you nervous, afraid. But we’ve been here all along—you just never noticed.

Along the way, something happened that I have still to forget.After one meeting, my friend Tino of LULAC emailed me, “This is what the Minutemen want.” Attached was a documentary video. The black and white photos of Latino families being forced into crowded boxcars reminded me powerfully of similar photos of Jewish families being loaded onto trains in Nazi-occupied areas of Europe during the same years.8.When the Great Depression hit, citizens of Mexican ancestry made a great scapegoat. Demagogues, sounding much like people we hear over the airwaves today, blamed them and called for mass deportations. Groups of armed vigilantes, most supported by local, state, and federal government, beat and kidnapped men walking down the street to work or home, visited homes with threats of violence and arrest, and drove families out without any of their possessions. They forced huge numbers of people without any of their belongings or food or water into railroad boxcars where the doors were locked shut and the people eventually dumped out in Mexico. The elderly, babies and pregnant women, those already sick—physically or mentally—suffered the most, and many died along the way. Twenty-five children and adults died on just one of these trains on its trip to the border.9.When my children were small, I would take them with me to the Westside, to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, where the grandmothers sold fresh tamales every Saturday to support the church. We would enter the cool basement where las Guadalupeñas would coo at Crystal and Niles en español. Crystal would respond by dancing around and laughing. Niles would try to hide his face in my pant legs, clinging tightly and crying until he pressed new creases. The old women would pack the still-steaming tamales, wrapped by the dozens in foil, into a paper bag and call out goodbyes to el niñito timido.On the way to the car, I would promise if he stopped crying we would visit La Fama, the panadería, for Mexican bread. We picked out thick, sugary cookie flags and pan dulce, carrying them all in a paper bag that began to show grease spots from the sweet treats inside before we got home.Or perhaps I would hold out the prospect of a visit to Sanchez Market for chicharrones, the real thing, large, bubbled, almost transparent from the deep-frying that made them so light and crunchy. While there, I would stock up on peppers and spices that couldn’t be found anywhere else in town as the kids relished their big chunks of fried pork rind.Back then, we gathered around the church and food—at weddings, after funerals, for quinceañeras, after First Communions, and at fundraisers for American GI Forum, the organization founded by decorated, returning Latino World War II veteranos when the American Legion wouldn’t allow them to join.Many women had a specialty food—tamales, enchiladas, mole, tostadas, arroz con pollo, sopa—that they were asked to bring. You always wanted to go if they had Lupe’s mole or Jennie’s enchiladas. They were better than you could get anywhere else unless you were lucky enough to belong to Lupe’s or Jennie’s family. But these women were generous and always shared with other families who were celebrating or mourning or just raising money for beloved causes.10.Many of those driven out in the 1930s were legal residents or citizens, naturalized and native-born. Children born and raised in this country were forced into a country they did not know with a language they did not know and often compelled to leave behind the birth certificates that proved their citizenship. Sixty percent of the 1.2 million people driven out of the country were citizens. Many of these families who were marched to the railroad cars and shipped out like so much freight owned their own homes and even had small businesses. All of this was forfeited to the mobs that kidnapped them and sent them out of the U.S.11.Herbert Hoover never made a formal policy of forced deportation, but elements within his government, along with state and local governments, arranged for the railroad cars and gave approval to the vigilantes. In some cases, it was actually government agents who drove people out of their homes. At times, private institutions also financed deportation boxcars. For example, the archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, paid for boxcars to take families out of the city, many of whom had lived there and worshipped as faithful Catholics since before the turn of the century. In fact, in southern California, hundreds of families were rounded up in 1931 as they attended Catholic services on Ash Wednesday.12.In Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, we have a large Chicano population that has been in the area since the turn of the twentieth century with third-generation and fourth-generation adult U.S. citizens who speak primarily (and often only) English, have college educations, and work as professionals. We also have a large, newer population, deriving from Central and South America as much as from Mexico, as often as not completely indigenous with little or no Spanish, speaking Nahuatl, Quechua, Q'eqchi'.I have often thought the great public horror evinced about this new wave of immigrants is due to their indigenous nature. The United States can hardly bear to see such large numbers of indigenous people as anything but threat when this country has worked so long and so hard at wiping out its own indigenous peoples through violence, disease, “education,” and the blood quantum rule the BIA has imposed on our indigenous nations that still endure.In 2007, my son Niles took a one-week European vacation. He flew home from London by way of Detroit. In Detroit, this non-Spanish-speaking, second-generation American citizen (on his father’s side), born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, was held for 24 hours by immigration authorities and refused entry into his own country, even though he had a passport. They were certain he was an illegal immigrant from Mexico trying to sneak into the U.S.Neither his valid documents nor his non-accented, perfectly colloquial English could outweigh his brown skin and Spanish last name. He was released and allowed to enter his own country only after his white boss confirmed over the telephone that he was a citizen and had been gainfully employed in a high-level professional position for seven years.To me, this is doubly galling because Niles is not only Chicano but also part Cherokee and part Choctaw. My children and I have several lines of ancestors who go back to the time before there was a United States of America. I have always since wondered just exactly how many illegal immigrants from Mexico named Niles have flown to England and toured the Continent before trying to sneak into the U.S. on a flight from London.13.People always are surprised to find Latinos in Kansas City—anywhere in the Midwest. We’re only supposed to congregate in Miami, New York, El Paso, Phoenix, and LA.Sometimes I want to ask, “Who did you think picked all those fruits and vegetables from the breadbasket of the country? Who worked in the meatpacking hellholes, if not the Mexicans and Indians? Who kept the trains cleaned, painted, and running, if not the African Americans and Mexicans?”Always the invisible poor, laborers doing the work no one else wanted. Now, it’s roofing and gardening, cleaning hotel rooms and offices at night. We’ve been here a long time, long enough to lose our language sometimes while we were gaining diplomas and degrees, but never to lose our culture completely. The newcomers make you nervous, afraid. But we’ve been here all along—you just never noticed.

We’ve Been Here All Along: 13 Ways of Looking at Latinos in the Midwest

by Linda Rodriguez

1.

I listen for the broken truth that speaks of what’s been stolen, what’s been cracked and smashed. Bit by bit, I try to put together pieces, fragments of what was, stories for my children to live on. I refuse the blindness and forgetfulness that would render me acceptable in my country’s eyes, this country that lies about what it did to its indigenous roots, about who provides the necessary labor for all the luxury in which we live. Our comfortable lives are built on bones, and how we long to forget!2.

Here in the middle of the country’s heart, I live surrounded by the liquid names I love—Arredondo, Villalobos, Siquieros, Duarte, Espinoza. We are a secret pool in the middle of this dry, often drought-cursed Bible Belt, petitioners of La Virgen de Guadalupe and Tonantzin with tall flickering novena candles set out on household altars, devourers of caldo, horchata, albondigas with tongues that roll “r”s and hiss our “z”s, dark faces, eyes, hair among all these pale ones.How did we come to be here in a land covered in ice half the year? How did we come to this place where no parrots fly free and flowers freeze to death? Surely it was not our doing.3.Though larger totals of Latinos were driven out of the border states during the Depression’s forced deportations, the usually isolated communities in the Midwest were hit the hardest—in some cases, losing over half their population overnight. Those remaining kept their heads down, hoping to avoid another violent outbreak. They made their children speak only English.Though that had not mattered. Many of those shipped to Mexico were citizens who spoke English fluently and little, if any, Spanish.The Midwestern communities became even more invisible. They just wanted to be left alone.4.When Federales chased Pancho Villa and his soldados over the countryside in and out of the small farms and ranches and the dusty little towns that supported them, each side of the conflict when it stopped for a rest would force all the men and boys in a village or on a farm to join its army. Worn out from the constant warfare of Mexico of that time, those men and boys—and their families—wanted to be left in peace. They fled to cities where men in suits from the north offered them money if they would migrate to the land of gringos to work on railroads or in meatpacking plants. The old streets-of-gold promise, and it sounded much better than getting shot in one army or another. Taking their families, they moved north to Chicago, Kansas City, and Topeka.5.Ironically, when the U.S. entered World War II and needed cannon fodder, politicians remembered those English-speaking, American-citizen kids that they'd forced from their own country. They sent military recruiters south. Large numbers of boys, driven by force from their country to a land where they didn’t speak the language and never fit in, signed up to go to Europe and the Pacific to fight for the country they loved—even if it didn’t love them.If you didn’t read about this in your school history books, don’t be surprised. Neither did I. This whole episode was like the internment of American citizens of Japanese descent in camps during World War II. After the paroxysm was over, we as a nation only wanted to forget what we had done.6.The oldest Latino community in Kansas City, Kansas, was built around an entire village removed from Michoacan and settled into broken-down boxcars beside the Kaw River. When I was younger, you could still see the boxcar origins of a few houses in the Oakland community of Topeka, Kansas, and the Argentine district in Kansas City, Kansas. Around the core of boxcar, wood siding was added. New rooms and additions were built over the years to make real homes.Few of these houses have survived the past four decades, but I still remember them, always surrounded with luxuriant vegetable and flower gardens in the tiny yard space around the houses—an emphatic statement of a people who could indeed make silk purses out of sows’ ears or real two- or three-bedroom homes out of broken-down boxcars.7.In 2007, Kansas City, Missouri, had a new mayor. He had just appointed a very active member of the local Minutemen organization to Kansas City’s most powerful board. I found the local Minutemen chapter’s website and read a call to go door-to-door in Kansas City, demanding to see proof of citizenship or legal status and making “citizen’s arrests” where the occupant could not or would not show these. It was clear from the rhetoric on the website that these would not be random visits but would target homes with occupants who had Spanish last names.I took this threat personally. So when my friend Freda asked me to come to an emergency press conference to show solidarity, I did. Leaders of Chicano/Latino civic organizations formed the Kansas City Latino Civil Rights Task Force to fight this appointment. We were sure this would all end quickly. We were wrong, of course. It took over six months of constant effort, national groups cancelling conventions in the city, and the cooperation of African American, Jewish, and Anglo groups.

Along the way, something happened that I have still to forget.After one meeting, my friend Tino of LULAC emailed me, “This is what the Minutemen want.” Attached was a documentary video. The black and white photos of Latino families being forced into crowded boxcars reminded me powerfully of similar photos of Jewish families being loaded onto trains in Nazi-occupied areas of Europe during the same years.8.When the Great Depression hit, citizens of Mexican ancestry made a great scapegoat. Demagogues, sounding much like people we hear over the airwaves today, blamed them and called for mass deportations. Groups of armed vigilantes, most supported by local, state, and federal government, beat and kidnapped men walking down the street to work or home, visited homes with threats of violence and arrest, and drove families out without any of their possessions. They forced huge numbers of people without any of their belongings or food or water into railroad boxcars where the doors were locked shut and the people eventually dumped out in Mexico. The elderly, babies and pregnant women, those already sick—physically or mentally—suffered the most, and many died along the way. Twenty-five children and adults died on just one of these trains on its trip to the border.9.When my children were small, I would take them with me to the Westside, to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, where the grandmothers sold fresh tamales every Saturday to support the church. We would enter the cool basement where las Guadalupeñas would coo at Crystal and Niles en español. Crystal would respond by dancing around and laughing. Niles would try to hide his face in my pant legs, clinging tightly and crying until he pressed new creases. The old women would pack the still-steaming tamales, wrapped by the dozens in foil, into a paper bag and call out goodbyes to el niñito timido.On the way to the car, I would promise if he stopped crying we would visit La Fama, the panadería, for Mexican bread. We picked out thick, sugary cookie flags and pan dulce, carrying them all in a paper bag that began to show grease spots from the sweet treats inside before we got home.Or perhaps I would hold out the prospect of a visit to Sanchez Market for chicharrones, the real thing, large, bubbled, almost transparent from the deep-frying that made them so light and crunchy. While there, I would stock up on peppers and spices that couldn’t be found anywhere else in town as the kids relished their big chunks of fried pork rind.Back then, we gathered around the church and food—at weddings, after funerals, for quinceañeras, after First Communions, and at fundraisers for American GI Forum, the organization founded by decorated, returning Latino World War II veteranos when the American Legion wouldn’t allow them to join.Many women had a specialty food—tamales, enchiladas, mole, tostadas, arroz con pollo, sopa—that they were asked to bring. You always wanted to go if they had Lupe’s mole or Jennie’s enchiladas. They were better than you could get anywhere else unless you were lucky enough to belong to Lupe’s or Jennie’s family. But these women were generous and always shared with other families who were celebrating or mourning or just raising money for beloved causes.10.Many of those driven out in the 1930s were legal residents or citizens, naturalized and native-born. Children born and raised in this country were forced into a country they did not know with a language they did not know and often compelled to leave behind the birth certificates that proved their citizenship. Sixty percent of the 1.2 million people driven out of the country were citizens. Many of these families who were marched to the railroad cars and shipped out like so much freight owned their own homes and even had small businesses. All of this was forfeited to the mobs that kidnapped them and sent them out of the U.S.11.Herbert Hoover never made a formal policy of forced deportation, but elements within his government, along with state and local governments, arranged for the railroad cars and gave approval to the vigilantes. In some cases, it was actually government agents who drove people out of their homes. At times, private institutions also financed deportation boxcars. For example, the archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, paid for boxcars to take families out of the city, many of whom had lived there and worshipped as faithful Catholics since before the turn of the century. In fact, in southern California, hundreds of families were rounded up in 1931 as they attended Catholic services on Ash Wednesday.12.In Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, we have a large Chicano population that has been in the area since the turn of the twentieth century with third-generation and fourth-generation adult U.S. citizens who speak primarily (and often only) English, have college educations, and work as professionals. We also have a large, newer population, deriving from Central and South America as much as from Mexico, as often as not completely indigenous with little or no Spanish, speaking Nahuatl, Quechua, Q'eqchi'.I have often thought the great public horror evinced about this new wave of immigrants is due to their indigenous nature. The United States can hardly bear to see such large numbers of indigenous people as anything but threat when this country has worked so long and so hard at wiping out its own indigenous peoples through violence, disease, “education,” and the blood quantum rule the BIA has imposed on our indigenous nations that still endure.In 2007, my son Niles took a one-week European vacation. He flew home from London by way of Detroit. In Detroit, this non-Spanish-speaking, second-generation American citizen (on his father’s side), born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, was held for 24 hours by immigration authorities and refused entry into his own country, even though he had a passport. They were certain he was an illegal immigrant from Mexico trying to sneak into the U.S.Neither his valid documents nor his non-accented, perfectly colloquial English could outweigh his brown skin and Spanish last name. He was released and allowed to enter his own country only after his white boss confirmed over the telephone that he was a citizen and had been gainfully employed in a high-level professional position for seven years.To me, this is doubly galling because Niles is not only Chicano but also part Cherokee and part Choctaw. My children and I have several lines of ancestors who go back to the time before there was a United States of America. I have always since wondered just exactly how many illegal immigrants from Mexico named Niles have flown to England and toured the Continent before trying to sneak into the U.S. on a flight from London.13.People always are surprised to find Latinos in Kansas City—anywhere in the Midwest. We’re only supposed to congregate in Miami, New York, El Paso, Phoenix, and LA.Sometimes I want to ask, “Who did you think picked all those fruits and vegetables from the breadbasket of the country? Who worked in the meatpacking hellholes, if not the Mexicans and Indians? Who kept the trains cleaned, painted, and running, if not the African Americans and Mexicans?”Always the invisible poor, laborers doing the work no one else wanted. Now, it’s roofing and gardening, cleaning hotel rooms and offices at night. We’ve been here a long time, long enough to lose our language sometimes while we were gaining diplomas and degrees, but never to lose our culture completely. The newcomers make you nervous, afraid. But we’ve been here all along—you just never noticed.

Along the way, something happened that I have still to forget.After one meeting, my friend Tino of LULAC emailed me, “This is what the Minutemen want.” Attached was a documentary video. The black and white photos of Latino families being forced into crowded boxcars reminded me powerfully of similar photos of Jewish families being loaded onto trains in Nazi-occupied areas of Europe during the same years.8.When the Great Depression hit, citizens of Mexican ancestry made a great scapegoat. Demagogues, sounding much like people we hear over the airwaves today, blamed them and called for mass deportations. Groups of armed vigilantes, most supported by local, state, and federal government, beat and kidnapped men walking down the street to work or home, visited homes with threats of violence and arrest, and drove families out without any of their possessions. They forced huge numbers of people without any of their belongings or food or water into railroad boxcars where the doors were locked shut and the people eventually dumped out in Mexico. The elderly, babies and pregnant women, those already sick—physically or mentally—suffered the most, and many died along the way. Twenty-five children and adults died on just one of these trains on its trip to the border.9.When my children were small, I would take them with me to the Westside, to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, where the grandmothers sold fresh tamales every Saturday to support the church. We would enter the cool basement where las Guadalupeñas would coo at Crystal and Niles en español. Crystal would respond by dancing around and laughing. Niles would try to hide his face in my pant legs, clinging tightly and crying until he pressed new creases. The old women would pack the still-steaming tamales, wrapped by the dozens in foil, into a paper bag and call out goodbyes to el niñito timido.On the way to the car, I would promise if he stopped crying we would visit La Fama, the panadería, for Mexican bread. We picked out thick, sugary cookie flags and pan dulce, carrying them all in a paper bag that began to show grease spots from the sweet treats inside before we got home.Or perhaps I would hold out the prospect of a visit to Sanchez Market for chicharrones, the real thing, large, bubbled, almost transparent from the deep-frying that made them so light and crunchy. While there, I would stock up on peppers and spices that couldn’t be found anywhere else in town as the kids relished their big chunks of fried pork rind.Back then, we gathered around the church and food—at weddings, after funerals, for quinceañeras, after First Communions, and at fundraisers for American GI Forum, the organization founded by decorated, returning Latino World War II veteranos when the American Legion wouldn’t allow them to join.Many women had a specialty food—tamales, enchiladas, mole, tostadas, arroz con pollo, sopa—that they were asked to bring. You always wanted to go if they had Lupe’s mole or Jennie’s enchiladas. They were better than you could get anywhere else unless you were lucky enough to belong to Lupe’s or Jennie’s family. But these women were generous and always shared with other families who were celebrating or mourning or just raising money for beloved causes.10.Many of those driven out in the 1930s were legal residents or citizens, naturalized and native-born. Children born and raised in this country were forced into a country they did not know with a language they did not know and often compelled to leave behind the birth certificates that proved their citizenship. Sixty percent of the 1.2 million people driven out of the country were citizens. Many of these families who were marched to the railroad cars and shipped out like so much freight owned their own homes and even had small businesses. All of this was forfeited to the mobs that kidnapped them and sent them out of the U.S.11.Herbert Hoover never made a formal policy of forced deportation, but elements within his government, along with state and local governments, arranged for the railroad cars and gave approval to the vigilantes. In some cases, it was actually government agents who drove people out of their homes. At times, private institutions also financed deportation boxcars. For example, the archdiocese of Kansas City, Kansas, paid for boxcars to take families out of the city, many of whom had lived there and worshipped as faithful Catholics since before the turn of the century. In fact, in southern California, hundreds of families were rounded up in 1931 as they attended Catholic services on Ash Wednesday.12.In Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, we have a large Chicano population that has been in the area since the turn of the twentieth century with third-generation and fourth-generation adult U.S. citizens who speak primarily (and often only) English, have college educations, and work as professionals. We also have a large, newer population, deriving from Central and South America as much as from Mexico, as often as not completely indigenous with little or no Spanish, speaking Nahuatl, Quechua, Q'eqchi'.I have often thought the great public horror evinced about this new wave of immigrants is due to their indigenous nature. The United States can hardly bear to see such large numbers of indigenous people as anything but threat when this country has worked so long and so hard at wiping out its own indigenous peoples through violence, disease, “education,” and the blood quantum rule the BIA has imposed on our indigenous nations that still endure.In 2007, my son Niles took a one-week European vacation. He flew home from London by way of Detroit. In Detroit, this non-Spanish-speaking, second-generation American citizen (on his father’s side), born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, was held for 24 hours by immigration authorities and refused entry into his own country, even though he had a passport. They were certain he was an illegal immigrant from Mexico trying to sneak into the U.S.Neither his valid documents nor his non-accented, perfectly colloquial English could outweigh his brown skin and Spanish last name. He was released and allowed to enter his own country only after his white boss confirmed over the telephone that he was a citizen and had been gainfully employed in a high-level professional position for seven years.To me, this is doubly galling because Niles is not only Chicano but also part Cherokee and part Choctaw. My children and I have several lines of ancestors who go back to the time before there was a United States of America. I have always since wondered just exactly how many illegal immigrants from Mexico named Niles have flown to England and toured the Continent before trying to sneak into the U.S. on a flight from London.13.People always are surprised to find Latinos in Kansas City—anywhere in the Midwest. We’re only supposed to congregate in Miami, New York, El Paso, Phoenix, and LA.Sometimes I want to ask, “Who did you think picked all those fruits and vegetables from the breadbasket of the country? Who worked in the meatpacking hellholes, if not the Mexicans and Indians? Who kept the trains cleaned, painted, and running, if not the African Americans and Mexicans?”Always the invisible poor, laborers doing the work no one else wanted. Now, it’s roofing and gardening, cleaning hotel rooms and offices at night. We’ve been here a long time, long enough to lose our language sometimes while we were gaining diplomas and degrees, but never to lose our culture completely. The newcomers make you nervous, afraid. But we’ve been here all along—you just never noticed.

Published on September 01, 2016 15:35

July 7, 2016

A Poem for Alton Sterling, Philando Castile,all the people executed by police, and the thousands of Native women and girls murdered and missing

It's dark out, my friends. I went to sleep last night, still mourning for Alton Sterling whose 15-year-old son is bereft because a policeman with a Facebook page full of white supremacist junk decided to shoot him while he lay helpless, pinned to the ground by cop knees, legs, and bodies. I woke this morning to news of the murder of Philando Castile in front of his four-year-old daughter (who was taken into police custody along with her mother for the crime of witnessing the killing) by a policeman so obviously terrified of dark skin that he shot a man who was complying with his orders four times. And more Indigenous women were raped, murdered, or have gone missing (probably raped and murdered) in Canada, the United States, and Mexico to add to the already-dizzying total of such women whose deaths are never even investigated because law enforcement doesn't think they're worth it.

The extra-judicial executions are stepping up. #BlackLivesMatter works hard to raise awareness and try to bring political power to bear on the situation. People of good minds and hearts of all colors gather and protest and sign petitions. Nothing seems to make any difference.

I can't cry anymore, but I can still write, so here's a poem. A dark one for a dark time.

I CAN'T CRY ANYMORE(A poem for Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, all the people executed by police, and the thousands of Native women and girls missing and murdered)

I can't cry anymorefor murdered brown men and boys,holding my breath for fearthe next will be one of mine.Can't cry anymore for brown womenexecuted, dying in custody, raped, murdered, missingand no one investigating my sisters, cousins.All my tears have boiled away in ragethat, even as these murders and extra-judicial executions multiply,publishers, producers, editors, writers, on-air personalitiescontinue to present the dark-skinned man as criminal, danger,someone to shoot on sight in self-defense,the dark-skinned woman as drunk, drugged slut deserving anything any man wants to do to her,no matter her own feelings or rights.Let's face it—brown skin abrogates all rightsin America.

So white America continues to fear the dark boogeymanand lust for/despise the loose-moraled exotic woman.So police see dark skin as a weapon in its own right that could murder them on sight if they don't shoot first.So sexual predators--#NotAllMen--see a woman of color as a come-on, sign of easy prey no sheriff will arrest for, no news outlet investigate.And the whole demented cycle, reaching back to the founding of this nation on the murder and enslavement of Indians and Africans and the fear of them,their just anger and desire for freedom,plays out again and again.There is rot at the root of the tree of libertyin America.

© 2016 Linda Rodriguez

The extra-judicial executions are stepping up. #BlackLivesMatter works hard to raise awareness and try to bring political power to bear on the situation. People of good minds and hearts of all colors gather and protest and sign petitions. Nothing seems to make any difference.

I can't cry anymore, but I can still write, so here's a poem. A dark one for a dark time.

I CAN'T CRY ANYMORE(A poem for Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, all the people executed by police, and the thousands of Native women and girls missing and murdered)

I can't cry anymorefor murdered brown men and boys,holding my breath for fearthe next will be one of mine.Can't cry anymore for brown womenexecuted, dying in custody, raped, murdered, missingand no one investigating my sisters, cousins.All my tears have boiled away in ragethat, even as these murders and extra-judicial executions multiply,publishers, producers, editors, writers, on-air personalitiescontinue to present the dark-skinned man as criminal, danger,someone to shoot on sight in self-defense,the dark-skinned woman as drunk, drugged slut deserving anything any man wants to do to her,no matter her own feelings or rights.Let's face it—brown skin abrogates all rightsin America.

So white America continues to fear the dark boogeymanand lust for/despise the loose-moraled exotic woman.So police see dark skin as a weapon in its own right that could murder them on sight if they don't shoot first.So sexual predators--#NotAllMen--see a woman of color as a come-on, sign of easy prey no sheriff will arrest for, no news outlet investigate.And the whole demented cycle, reaching back to the founding of this nation on the murder and enslavement of Indians and Africans and the fear of them,their just anger and desire for freedom,plays out again and again.There is rot at the root of the tree of libertyin America.

© 2016 Linda Rodriguez

Published on July 07, 2016 09:46

April 29, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote in High School

"Coyote in High School" is the final poem of my sequence of Coyote poems that I've posted like a serialized chapbook for #NationalPoetryMonth. In this poem, I take a look at the reality behind the bad boy archetype that's so common in books, movies, and television.

"Coyote in High School" is the final poem of my sequence of Coyote poems that I've posted like a serialized chapbook for #NationalPoetryMonth. In this poem, I take a look at the reality behind the bad boy archetype that's so common in books, movies, and television. The Fonzie character in the TV series, Happy Days, may have been the "cool" guy everyone else wanted to be, but his horizons were most likely limited by his family situation and his position in the class structure of his town and his country.

COYOTE IN HIGH SCHOOL

What is it about the bad boy,the one in black leatheron too loud, too fast wheels,the one we were warned against in high school?Behind the scenes of proms and sock hopsand classes sanitized so we wouldn’t catchthe germs of thought,all the girls had dreams about that bad boythat we couldn’t even admit to ourselveswhile our dates were safe white bread.

When we walked down the halls to lunch,we knew the bad boys,leaning against the wallsin cocky poses of insolence and threat,were using their X-ray vision to see usnaked or--worse--in our schoolgirl underwear.Some of us hunched over our booksand scuttled past that leering line.Some of us stretched erect and strutted slightlyon our way beyond their limited prospects.

A classic teacher’s pet,I snuck out twice with dangerous boys,sideswiped by the kind of temporary insanitythat catches your heart in your throat,roller-coaster, sky-diving, over-the-falls-in-a-barrelfear and excitement blended into one shiver.

The first, in senior year, was careful with me,insistent on leaving the good-girl scholar a virgin.He didn’t want to hurt me, he said, didn’t want to be bad news. I didn’t tell himmy father had taken care of that years earlier.I didn’t answer his phone calls after that, either.A couple of years later, the second one took me to his roomon the back of his Harley and made love to meall night, telling me he knew he wasn’t good enoughfor a girl like me, but he’d make me happy anyway.He did that, and I avoided him thereafter.

I went with each only once,though they were more gentle than the general runof jocks and frat boys my friends dated.After all, the insanity had been only temporary.I had friends who’d stepped over the line too oftenor too long and paid and paid—as did some of us who mated with business or psych majors,just in different ways.

Looking back, I wonderif anyone ever warns the hard-shelled boys in leatheragainst the honor roll girls?

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 29, 2016 04:00

April 28, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote at Your Wedding

"Coyote at Your Wedding," the 9th and penultimate poem in the sequence of Coyote poems I've posted for #NationalPoetryMonth, brings this particular narrative of Coyote to an end. The final poem is a commentary on the class situation of the bad boy/Coyote archetype, and the way the deck is stacked against such people (and even supernatural beings).

"Coyote at Your Wedding," the 9th and penultimate poem in the sequence of Coyote poems I've posted for #NationalPoetryMonth, brings this particular narrative of Coyote to an end. The final poem is a commentary on the class situation of the bad boy/Coyote archetype, and the way the deck is stacked against such people (and even supernatural beings).COYOTE AT YOUR WEDDING

He left his shotgun in the car,though he longed to stormthrough the doors and aima blast at the groom’s head.He has no invitation,of course, and hopes some fool tries to make himleave. He’s a black-leather thunderheadamong the white flowers.He wants to make a scene,commit a crime, scandalizethe guests, bloodythe groom’s nose, carry offthe bride kicking and screaming.

As he walks through the crowd,the invited ones moveto give him spaceas they would any wild predatorstalking through the church.Trouble swirls around him, creating a wake of racing heartsand choked-back squeals. He wantsto smash the flowers,throw food at the walls, rip the bridesmaid’sdresses, curse the minister.

He’s looking but can’t find you because you’re waitingoff scene for your musical cueto enter in procession.Coyote drops hardinto an aisle seatin the back rowwhere he can grab youand take off when you come in reach.He props one booton the back of the seat in frontto block anyone else’s accessto his row. He doesn’t knowhe’s sitting on the groom’s side.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 28, 2016 04:00

April 27, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote at the Park

The 8th poem in the serialized chapbook of Coyote poems that I'm posting for #NationalPoetryMonth is "Coyote at the Park." In this poem, for a change, Coyote is the one being watched while unaware of the watcher.

The 8th poem in the serialized chapbook of Coyote poems that I'm posting for #NationalPoetryMonth is "Coyote at the Park." In this poem, for a change, Coyote is the one being watched while unaware of the watcher.As I thought more and more about the bad boy archetype in fiction, TV, and movies, I came to realize that it has its root in class. The bad boy is always an outsider, poor, working class, rough-edged, not one of the privileged class. He may have found a way to make himself wealthy, like Gatsby, but he always carries that taint of the interloper. He has charm, intelligence, and bags of sex appeal, but he's still from the wrong side of town.

COYOTE AT THE PARK

Coyote sits and waits.He’s asked you to meet himhere where you’ll feel safe,as ifanywhere were safewith Coyote.You spot himas soon as you enterthrough the stone arches,all that dark shiningin the sunlight.Teenaged girls in tight pastelsgiggle and flirtwith more troublethan they could ever handle,and Coyote sends themoff with a wink.He’s in a good mood,waiting for you to comeas you promised,benevolent predatorrefusing the preyon a whim or the hopeof something better.

From behind the stone,you watch his long lithe bodystretched on the wooden benchas if to soak up the heatstored in its slats,grace unconsciousof your secret admiration.Coyote is a contented mantoday when you are expectedany momentbefore he realizesyou’re gone.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 27, 2016 04:00

April 26, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote in Black Leather

The 7th poem in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth that I'm posting to this blog as a kind of serialized chapbook is "Coyote in Black Leather." I wrote this poem immediately after writing the poem, "Outside Your House at Midnight, Coyote" (posted here yesterday). This is one of the most popular and reprinted poems I've ever written.

The 7th poem in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth that I'm posting to this blog as a kind of serialized chapbook is "Coyote in Black Leather." I wrote this poem immediately after writing the poem, "Outside Your House at Midnight, Coyote" (posted here yesterday). This is one of the most popular and reprinted poems I've ever written.After writing this poem, I began to envision a whole sequence of poems about the bad boy archetype as Coyote in human form. Coyote is the trickster, the troublemaker, and yet often an ally of humans, even as he tries to seduce and exploit them. That seemed a good match for the anti-hero that the bad boy figure in literature, film, and television so often turns out to be.

COYOTE IN BLACK LEATHER

Coyote slides on black leatherover the T-shirt that reins in biceps, shoulders, chest.Dark jeans and biker boots cover the rest of his long, lithe body as he invadesyour everyday, suburban lifelike a growl.You avert your eyes, pretendyou don’t watchhis tight, hard body, his mocking face.You know he’s bad, doesn’t belong.Besides, seeing him makes your face too red, your breath too short, your bones too soft, your clothes too tight. You pretendnot to peek, don’t want him to catch you lookingat the hungry way he stares at you.Coyote has no class.

Coyote is your secret.You tell him it’s more exciting that way.He lifts the eyebrow bisected by a scar and staresyou into silence. He knowsyou’re ashamed. He thinksyou’re ashamed of him.Coyote takes you to dangerous places.In dark, dirty bars, he threatens drunksand fights to protect you.Coyote takes you where no one else can.Coyote takes youwhere you can’t admit you want to go.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 26, 2016 04:00

April 25, 2016

National Poetry Month--Outside Your House at Midnight, Coyote

"Outside Your House at Midnight, Coyote" is the 6th in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth. It was the second one written, however. "3 O'Clock in the Morning, Alone" was the first I'd written with the Coyote avatar. Several years later, my youngest son had inveigled me into watching the TV series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and a sizzling scene of a lovesick Spike watching outside Buffy's window at night inspired me to write this poem. And this one then unleashed several others.

"Outside Your House at Midnight, Coyote" is the 6th in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth. It was the second one written, however. "3 O'Clock in the Morning, Alone" was the first I'd written with the Coyote avatar. Several years later, my youngest son had inveigled me into watching the TV series, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and a sizzling scene of a lovesick Spike watching outside Buffy's window at night inspired me to write this poem. And this one then unleashed several others.OUTSIDE YOUR HOUSE AT MIDNIGHT, COYOTE

stands in shadows, only the red eyeof his cigarette showing his presence.He watches lights in windowsdownstairs and your silhouetteagainst curtains as you movefrom room to room, readying for bed.He grinds cigarette into the groundwith his boot, to join the otherslittering the spot where he lurks,across the street, vacant lot,under trees along the fence line.

As you switch off lights,room by room, and climb stairsto your bed, Coyote moves outof the shadows, closer to youby a few feet more. The outer raysof the light on the cornercatch his sharp features, golden hair,the hunger on his face.

He watches your light click on upstairs.Closing his eyes, Coyote can see withinyour walls as you undress and slide undercovers. Tendons in his neck stand out,rigid with tension, and he swallows his ownwanting with pain. He opens his eyesto the dark again, watches your last lightwink out, whispers something so softeven he won’t hear, stays to witnessthe vulnerability of your restless body.Sleep. Coyote’s standing watch.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 25, 2016 04:00

April 24, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote Invades Your Dreams

(Note: I have no image for this post. I want to warn you not to search for "images coyote dreams" on the internet. It seems there's a popular trap used in hunting coyotes that's called "pipe dream." Your stomach will take hours to settle down from the images of bloody coyotes entrapped, dead in groups and hung on lines like fish on a stringer. Even a dreamcatcher made of coyote skin, head, and tail.)

This is the 5th in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth, "Coyote Invades Your Dreams." The dream world is, of course, a natural for Coyote since he's a supernatural being who has taken on human form. He can come and go there even more easily than he can in the modern material world we all live in.

COYOTE INVADES YOUR DREAMS

You’re staying clearof him. Just becauseyou noticed him onceor twice doesn’t mean you wantanything to do with him.He’s beneath you—and above you and inside youin your dreams. His mouthdrinks you deep, and you comeup empty and gaspingfor air and for him. That traitor,your body, clings to him like a liferaft in this hurricaneyou’re dreaming. His faceabove yours loses its knowingsmile as he takes you. Again,this night, you drownin your own desire. Coyotemarks you as his.You wake to the memoryof a growl.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

This is the 5th in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth, "Coyote Invades Your Dreams." The dream world is, of course, a natural for Coyote since he's a supernatural being who has taken on human form. He can come and go there even more easily than he can in the modern material world we all live in.

COYOTE INVADES YOUR DREAMS

You’re staying clearof him. Just becauseyou noticed him onceor twice doesn’t mean you wantanything to do with him.He’s beneath you—and above you and inside youin your dreams. His mouthdrinks you deep, and you comeup empty and gaspingfor air and for him. That traitor,your body, clings to him like a liferaft in this hurricaneyou’re dreaming. His faceabove yours loses its knowingsmile as he takes you. Again,this night, you drownin your own desire. Coyotemarks you as his.You wake to the memoryof a growl.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 24, 2016 04:00

April 23, 2016

National Poetry Month--Coyote on the Telephone

Here is the fourth in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth, "Coyote on the Telephone." I wanted to write this poem to demonstrate the power of Coyote's seductive voice and persuasive words.

Here is the fourth in my sequence of Coyote poems for #NationalPoetryMonth, "Coyote on the Telephone." I wanted to write this poem to demonstrate the power of Coyote's seductive voice and persuasive words.Coyote, of course, is famous for his use of the word. He can talk himself out of almost anything, which is good for him because he usually talks himself into all kinds of trouble, taking someone else with him who may not be as adept at sidestepping the negative consequences when they come slamming down.

COYOTE ON THE TELEPHONE

Coyote calls you on the phone,asks, “Where have you been all my life?”in a voice that climbs inside your headand crawls down your backboneto your hips. He asks, “Whencan I see you again?” Your brainsays never, but his voice stops itand with some other part of your body, you reply, “Wheneveryou want.” Coyote laughs, low and sultry,and you shiver, knowing how much trouble you’re in.

You call Coyote. You’ve sworn you won’t, not again, but your fingerspress the numbers on their own without the brain’ssupervision. Your brain’s notdoing too well when Coyoteis near--or even the thought of him. When you say, “I shouldn’t have called; I swore I wouldn’t,”he laughs that way he hasthat sends your synapses flyingand your skin growing too hotand tight for your bones that are melting as he growls.You know you ought to hang upand your finger sits above the TALK button throughout the conversation but only pushesit after the dial tone kicks in.

You never thought you were weakbefore. Coyote’s taught youwhat you never wanted to learn.

Published in Heart’s Migration (Tia Chucha Press, 2009)

Published on April 23, 2016 04:00