Roy Miller's Blog, page 277

February 10, 2017

Harlem Histories and Boardroom Lessons

book traces the peak of the Jewish population in Harlem before World War I to stirrings of a revival today." data-mediaviewer-credit="New York University Press" itemprop="url" itemid="https://static01.nyt.com/images/2017/...

This book traces the peak of the Jewish population in Harlem before World War I to stirrings of a revival today.

Credit

New York University Press

Nearly a century ago, during the Harlem Renaissance, the activist and writer James Weldon Johnson described his neighborhood as “a city within a city, the greatest Negro city in the world.” But he wondered, “Are the Negroes going to be able to hold Harlem?”

“When colored people do leave Harlem,” he wrote, “their homes, their churches, their investments and their businesses, it will be because the land has become so valuable that they can no longer afford to live on it.”

He was correct in predicting in 1925 that “the date of another move northward” — as when blacks had displaced Jews, long after Harlem had begun as a Dutch suburb — “is very far in the future.” Three new books explore Harlem’s evolution since then.

In “The Jews of Harlem: The Rise, Decline and Revival of a Jewish Community” (New York University Press, $35), Jeffrey S. Gurock, a professor of Jewish history at Yeshiva University, traces the peak of the Jewish population there before World War I to stirrings of a revival today.

Photo

This book argues that the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s was not a distant, passing phase, but “a period that left indelible influence” on black culture and beyond.

Credit

Praeger

In “Harlem: The Crucible of Modern African American Culture” (Praeger, $48), Lionel C. Bascom, who teaches in the department of writing, linguistics and creative process at Western Connecticut State University, argues that the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s was not a distant, passing phase, but “a period that left indelible influence” on black culture and beyond.

Continue reading the main story

Still, by the early 21st century, greater Harlem’s majority population was no longer black, as Johnson had foretold. What happened to the poorest tenants and small shopkeepers? Would the neighborhood lose its cultural cachet as its inhabitants were increasingly priced out?

In reviewing Kay S. Hymowitz’s “The New Brooklyn: What It Takes to Bring a City Back,” Alan Ehrenhalt, a senior editor at Governing magazine, agreed with the author recently that continuing urban decline makes everyone a loser. Gentrification can produce both losers and winners.

Photo

This book explores Harlem’s resistance to renewal as it becomes the home to destination restaurants and $3 million townhouses.

Credit

Harvard University Press

In “The Roots of Renaissance: Gentrification and the Struggle Over Harlem” (Harvard University Press, $39.95), Brian D. Goldstein, an assistant professor of architecture at the University of New Mexico, explores the neighborhood’s resistance to renewal as it becomes the home to destination restaurants like Red Rooster Harlem, a soon-to-open Whole Foods Market and $3 million townhouses.

“Community development, which had once stood for a radical, communitarian and collectivist ideal of the future city,” Professor Goldstein writes, “instead came to represent an image of Harlem as a place whose revitalization would proceed from its entrance into a so-called economic mainstream.”

A Future President Drops In

In “The Activist Director: Lessons From the Boardroom and the Future of the Corporation” (Columbia Business School, $27.95), the high-powered lawyer Ira M. Millstein describes New York City’s mid-1970s fiscal crisis as “among the worst examples of poor corporate governance oversight I have seen.”

He writes that he was one of three confidants of Mayor Abraham D. Beame whom Gov. Hugh L. Carey enlisted to persuade Mr. Beame to resign (they refused out of loyalty to the mayor), and reveals the bizarre back story behind the mayor’s coveted endorsement of Jimmy Carter for the Democratic presidential nomination.

Mr. Millstein and Howard J. Rubenstein brought Mr. Carter to Gracie Mansion, but the mayor refused to see him. “Howard begged him to, and he finally agreed to come down to the meeting,” Mr. Millstein recalled, but just sat there, his hands folded in front of him, listening to Mr. Carter’s entreaties, and then returning upstairs without saying a word.

“Totally frustrated, Howard suddenly blurted out, ‘The mayor endorses you,’” Mr. Millstein wrote. “Carter flashed his trademark toothy smile, said, ‘That’s wonderful!’ and scooted out.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Harlem Histories and Boardroom Lessons appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?

The following is from Kathleen Collins's story collection, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? Collins, who died in 1988 at age forty-six, was an African-American playwright, writer, filmmaker, director, and educator from Jersey City. She was the first black woman to produce a feature length film.

EXTERIORS

“Okay, it’s a sixth-floor walk-up, three rooms in the front, bathtub in the kitchen, roaches on the walls, a cubbyhole of a john with a stained-glass window. The light? They’ve got light up the butt! It’s the tallest building on the block, facing nothin’ but rooftops and sun. Okay, let’s light it for night. I want a spot on that big double bed that takes up most of the room. And a little one on that burlap night table. Okay, now light that worktable with all those notebooks and papers and stuff. Good. And put a spot on those pillows made up to look like a couch. Good. Now let’s have a nice soft gel on the young man composing his poems or reading at his worktable. And another soft one for the young woman standing by the stove killing roaches. Okay, now backlight the two of them asleep in the big double bed with that blue-and-white comforter over them. Nice touch.

“Okay, now while they’re asleep put a spot on the young woman smiling in that photograph taken on the roof of the building and on the young man smoking a pipe in that photograph taken in the black rocking chair, and be sure to light the two of them hugging each other in that photograph taken in the park around the corner. Good. Now backlight the young woman as she lifts that enamel counter covering the bathtub and put a little light on him undressing her and a nice soft arc on the two of them nude in the doorway. Nice touch. Now dim the light. He’s picking at her and teasing her. No, take it way down. She looks too anxious and sad. Keep it down. He looks too restless and angry. Down some more. She’s just trying to please him. It can stay down. She’s just waiting at the window. No, on second thought, kill it, he won’t come in before morning. Okay. Now find a nice low level while they’re lying without speaking. No, kill it, there’s too much silence and pain. Now fog it slightly when he comes back in the evening and keep it dim while they sit on the bed. Now, how about a nice blue gel when he tells her it’s over. Good. Now go for a little fog while she tries not to cry. Good. Now take it up on him a little while he watches her coldly, then up on her when she asks him to stay. Nice. Now down a bit while it settles between them and keep it down while he watches her, just watches her, then fade him to black and leave her in the shadow while she looks for the feelings that lit up the room.”

Article continues after advertisement

From the book WHATEVER HAPPENED TO INTERRACIAL LOVE? By Kathleen Collins. Copyright © 2016 by The Estate of Kathleen Conwell Prettyman. Reprinted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

The post Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Profits Jump at HarperCollins

Profits jumped 32% at HarperCollins in the second quarter of fiscal 2017 over the comparable period in fiscal 2016. EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) was $75 million in the quarter ended December 31, 2016, up from $57 million a year ago. Revenue in the quarter rose 4%, to $466 million.

The revenue gain was attributed to a mix of strong frontlist sales from such titles as The Magnolia Story and Chaos as well as continued solid sales of Jesus Calling and Jesus Always (both by Sarah Young) and Hillbilly Elegy.

Led by digital audiobooks, digital sales increased 3% in the quarter and accounted for 16% of HC revenues, according to HC parent company News Corp.

For the first half of fiscal 2017, which ends June 30, 2017, HC’s revenues were flat at $855 million compared to the first half of fiscal 2016. EBITDA was up 24%, to $123 million.

The post Profits Jump at HarperCollins appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Pick Your Favorite Cover! | WritersDigest.com

The post Pick Your Favorite Cover! | WritersDigest.com appeared first on Art of Conversation.

February 9, 2017

Barbara Harlow, Scholar on Perils of Resistance Writing, Dies at 68

Prof. Barbara Harlow in an undated photo.

Credit

Tarek El-Ariss

Barbara Harlow, a scholar and author who brought issues of human rights and postcolonialism into the classroom through her studies of African, Arab and Latin American fiction and the writing of women in prison, died on Jan. 28 in Austin, Tex. She was 68.

The cause was esophageal cancer, said Elizabeth Cullingford, the chairwoman of the English department at the University of Texas at Austin, where Professor Harlow had taught since 1985.

Professor Harlow held multiple degrees in French literature when she accepted her first teaching post, at the American University in Cairo, in 1977. She immersed herself in contemporary Arab literature and became a passionate advocate for the Palestinian cause.

Her seminal study, “Resistance Literature,” published in 1987, was one of the first works in English to examine the fiction produced during national liberation struggles in the third world.

One of her central premises was that imaginative writing was a way to gain control over “the historical and cultural record.” This, she wrote, “is seen from all sides as no less crucial than the armed struggle.” The book became a standard text in postcolonial studies.

Continue reading the main story

In “Barred: Women, Writing and Political Detention” (1992), she turned her attention to literature by and about political prisoners in Northern Ireland, Israel and other countries.

Her preoccupation with the perils of the written word in a charged political environment led her to write “After Lives: Legacies of Revolutionary Writing” (1996), a study of three writers who were assassinated.

The first, Ghassan Kanafani, a spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine who was killed by the Mossad (the Israeli intelligence service) in 1972, was a figure close to her heart. In 1984 she translated a collection of his short stories under the title “Palestine’s Children.”

Her two other subjects were Roque Dalton, a Salvadoran poet executed by fellow members of the People’s Revolutionary Party during the Salvadoran civil war in 1975, and the white South African anti-apartheid activist Ruth First, assassinated by the South African police in 1982. The fates of all three were encapsulated in a line Professor Harlow quoted from the Syrian poet Adonis: “You die because you are the face of the future.”

Barbara Jane Harlow was born on Dec. 18, 1948, in Cleveland. Her father, Lawrence, was a chemical engineer. Her mother, the former Lucille Johnson, worked as a secretary. Her father died when she was young, her mother married Francis Foley, and Barbara grew up in Alabama and Massachusetts.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in French and philosophy from Simmons College in Boston in 1970 and a master’s degree in Romance languages and literatures from the University of Chicago in 1972, she studied in Paris at the École Pratique des Hautes Études and the École Normale Supérieure, and in Berlin at the Free University.

On returning to the United States, she completed her doctorate in comparative literature in 1977 at the State University of New York, Buffalo, under the poststructuralist Eugenio Donato. She wrote her dissertation on translations of Proust. She was an early translator of Jacques Derrida, producing an English version of his “Spurs: Nietzsche’s Styles” for the University of Chicago Press in 1979.

Professor Harlow taught at Wesleyan University and Hobart and William Smith Colleges before joining the English department at the University of Texas. There, she and several colleagues created the Ethnic and Third World Concentration, a course of study in which students read the literature of recently decolonized nations alongside the writings of ethnic minorities in the United States.

She lived in Clarksville, Tex., and is survived by two sisters, Ann Harlow and Karen Kelleher.

Professor Harlow was an editor of several key postcolonial texts. With Ferial Ghazoul, she edited “The View From Within: Writers and Critics on Contemporary Arabic Literature” (1994). She and her English department colleague Mia Carter edited “Imperialism and Orientalism: A Documentary Sourcebook” (1999), “Archives of Empire: From the East India Company to the Suez Canal” (2003) and “Archives of Empire: The Scramble for Africa” (2003).

Continue reading the main story

The post Barbara Harlow, Scholar on Perils of Resistance Writing, Dies at 68 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Perseus Purchase Boosts Lagardère 2016 Revenue

Total revenue at Lagardère Publishing rose 2.6% in 2016, to 2.26 billion euros. The increase includes a 70 million euro ($74.6 million) contribution from the Perseus Books Group publishing division, which Hachette Book Group acquired in March.

The strongest performer in the publishing group was the company’s U.K. division, where sales increased 11.0% helped by the success of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Revenue in France increased 1.5%.

The sales improvement for the full year came despite a 2.0% dip in fourth quarter revenue. The drop in the final period was due in part to a 12.4% decline in sales at HBG, which Lagardère said was due to a “less intensive release schedule” compared to the final quarter of 2015. HBG had gains in audiobook sales and in its distribution business.

In a statement, HBG CEO Michael Pietsch said, “Despite the dip in sales in the fourth quarter, Hachette’s excellent publishing paid off beautifully in 2016, with one of our very best years for bestsellers, and two of the year’s biggest awards”—the National Book Award in Nonfiction for Stamped from the Beginning by Ibram X. Kendi and the 2016 Caldecott Medal for Finding Winnie by Lindsay Mattick and illustrated by Sophie Blackall.

The major releases driving sales in 2016 include Nicholas Sparks’s Two by Two, David Baldacci’s The Last Mile, Lin-Manuel Miranda and Jeremy McCarter’s Hamilton: The Revolution, James Patterson and Maxine Paetro’s 15th Affair, Patterson’s Cross the Line, and Michael Connelly’s The Wrong Side of Goodbye.

The post Perseus Purchase Boosts Lagardère 2016 Revenue appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Colson Whitehead on George Saunders’s Novel About Lincoln and Lost Souls

Credit

Jason Holley

LINCOLN IN THE BARDO

By George Saunders

343 pp. Random House. $28.

It’s a very pleasing thing to watch a writer you have enjoyed for years reach an even higher level of achievement. To observe him or her consolidate strengths, share with us new reserves of talent and provide the inspiration that can only come from a true artist charting hidden creative territory. George Saunders pulled that trick off with “Tenth of December,” his 2013 book of short stories. How gratifying and unexpected that he has repeated the feat with “Lincoln in the Bardo,” his first novel and a luminous feat of generosity and humanism.

“Escape From Spiderhead,” one of the gems in “Tenth of December,” closed with a young man reckoning with his demise and saying goodbye to the world. “Lincoln in the Bardo” chooses a similar moment as its arena, unfolding in a Washington, D.C., cemetery in 1862, where a cohort of lost souls alternately apprehend, deny and resist the fact of their deaths. The bardo of the title is the transitional state in Buddhism, where the consciousness resides between death and the next life; for non-Buddhists, it is a recognizable limbo, full of milling entities who for one reason or another will not take the next step of the journey. Like the ghosts we know from stories, they are tied to their former existences, trapped by an idea of themselves, and can’t leave until they are ready; perhaps you recognize their dilemma from your own life, when you have been stuck between one obsolete version of yourself and the new version waiting just ahead. Maybe all you need is the right push.

Saunders gives us three tour guides to explain the rules of this afterworld. Hans Vollman calls his coffin a temporary “sick-box”; when he recovers, he will finally consummate his marriage (there have been complications). As long as Vollman clings to this wish, he’s dallying among the tombstones. Roger Bevins III is a love-struck suicide who decided, as his blood drained from his veins, to follow his gay “predilection.” He, too, is confined to bardo until he can accept that his resolve arrived too late and that he has kicked the bucket. The Rev. Everly Thomas is the only spirit who is aware of where and why everyone is stuck, and he has his own reasons for tarrying.

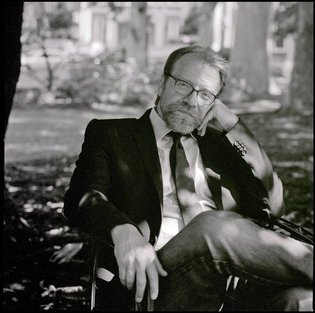

Photo

George Saunders

Credit

David Crosby

Three guides, and one guest of honor: Willie Lincoln, the 11-year-old son of the president. The “sort of child people imagine their children will be, before they have children,” he has caught his death of cold. The novel spans the night of his burial, as his presence upends the order of the cemetery. For one thing, “young ones are not meant to tarry” — unburdened by a lifetime’s accumulation of failures and regret, they usually pass over quickly. But a visit by his grieving father agitates the boy, as well as his graveyard neighbors. Making his way to his son’s crypt in the darkness, the president is an “exceedingly tall and unkempt fellow” who “might have been . . . a sculpture on the theme of loss,” and his demonstration of love calls up all sorts of weird feelings in the lingering souls. “It was cheering. It gave us hope,” Reverend Thomas says, “as if one were still worthy of affection and respect” even in this debased state. Roger Bevins III draws a similarly optimistic conclusion. “We were perhaps not so unlovable as we had come to believe,” he says. If the spirits can persuade this boy to undertake his rightful departure to the Other Side, they might be saved as well. It will be a long night.

The souls crowd around this uncanny child. As the cast grows, so does our perspective; the novel’s concerns expand, and we see this human business as an angel does, looking down. In the midst of the Civil War, saying farewell to one son foreshadows all those impending farewells to sons, the hundreds of thousands of those who will fall in the battlefields. The stakes grow, from our heavenly vantage, for we are talking about not just the ghostly residents of a few acres, but the citizens of a nation — in the graveyard’s slaves and slavers, drunkards and priests, soldiers of doomed regiments, suicides and virgins, are assembled a country. The wretched and the brave, and such is Saunders’s magnificent portraiture that readers will recognize in this wretchedness and bravery aspects of their own characters as well. He has gathered “sweet fools” here, and we are counted among their number.

Readers with conservative tastes may (foolishly) be put off by the novel’s form — it is a kind of oral history, a collage built from a series of testimonies consisting of one line or three lines or a page and a half, some delivered by the novel’s characters, some drawn from historical sources. The narrator is a curator, arranging disparate sources to assemble a linear story. It may take a few pages to get your footing, depending. The more limber won’t be bothered. We’ve had plenty of otherworldly choruses before, from Grover’s Corners to Spoon River, and with so many walking dead in the pop culture nowadays, why not a corresponding increase in the talking dead? Are the nonfiction excerpts — from presidential historians, Lincoln biographers, Civil War chroniclers — real or fake? Who cares? Keep going, read the novel, Google later.

Though I’ve met George Saunders a few times, we’re not buddy-buddy. I might lend him 10 bucks if he asked — I trust he’s good for it — but given how rarely our paths cross I know it would be a while before I saw it again, and that’s O.K. As with you, probably, I know him chiefly through his work, including “Pastoralia” and “CivilWarLand in Bad Decline,” his satirical diagnoses of our post-post-modern condition: our theme park life, mass-produced existential writhings, the communal pig-wallow in the mud pits of consumerism. But if the historical theme park in “CivilWarLand” was a stage for its workers’ ludicrous miseries, the war here is a crucible for a heroic American identity: fearful but unflagging; hopeful even in tragedy; staggering, however tentatively, toward a better world.

The father must say goodbye to his son, the son must say goodbye to the father. Abraham Lincoln must stop being the father to a lost boy and assume his role as a father to a nation, one on the brink of cataclysm. It is a perilous moment, the sort that comes along every so often, where it seems the country is listing and about to tip and only steady hands can right the ship. Survival depends not only on the captain, but on all aboard. Here we insert the common observation that the inanity of modern life has left the satirist unable to compete; pour one out for the absurdists among us. But events sometimes conspire to make a work of art, like a novel set in the past, supremely timely. In describing Lincoln’s call to action, Saunders provides an appeal for his limbo denizens — for citizens everywhere — to step up and join the cause. As one graveyard slave puts it, inspired by the great man in his mourning: “Sir, if you are as powerful as I feel that you are, and as inclined toward us as you seem to be, endeavor to do something for us, so that we might do something for ourselves. We are ready, sir; are angry, are capable, our hopes are coiled up so tight as to be deadly, or holy: Turn us loose, sir, let us at it, let us show what we can do.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Colson Whitehead on George Saunders’s Novel About Lincoln and Lost Souls appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Edgar Allan Poe, Editor and Original Hatchet Man

During Poe’s lifetime, he was just as well known for curation and criticism as he was for his short stories. From 1835 to 1846 alone, Poe worked as an editor for four different magazines. This kept him financially afloat—just barely. It also provided him a platform from which to gut his inferiors (Poe was popularly known as “The Tomahawk Man”) and applaud those he admired. And it was through his fiction and criticism both that Poe intended to change American publishing; as he wrote in a letter to his older brother, “If I fully succeed in my purposes I will not fail to produce some lasting effect upon the growing literature of the country.”

William Burton, an English actor living in Philadelphia, founded Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine in 1837. The magazine targeted a general audience and included fiction and poetry as well as commentary on theater and sporting life. In July 1839, overwhelmed with his work on the stage, Burton hired Poe to help with the magazine.

Poe was paid $10 a week for dedicating his attention to the editorial duties of Burton’s. He agreed to contribute 11 pages of original material a month, and he had his name added next to William Burton’s on the cover. In September of that same year, Poe’s contributor pages included “The Fall of the House of Usher,” his now infamous haunted story of familial sickness and incest in a crumbling mansion. But what else was in that issue? What was Poe like as an editor? And how did he choose to contextualize one of his most famous stories?

Article continues after advertisement

In addition to “Usher,” the September 1839 issue of Burton’s contains a lot of maritime stories and pirates. There are anxious dandy men and vulnerable waifish women. Some contributions serve as tributes to perceived heroes, others as takedowns of rude morons. The issue opens with a four-page biography of one Richard Penn Smith, an American playwright and contemporary of Poe and Burton’s. The passage seems like more of a strategic entry than anything else; writers and editors of the time commonly traded compliments and barbs within the pages of their respective publications. And this particular biography is overly personal and specific, invested heavily in the minutiae of Smith’s professional life, concluding with the information that Smith is also Secretary of Comptrollers of Public Schools, “a situation that yields him a handsome income.”

Fortunately, the content improves from there, with two chapters from a serialized novel called “The Privateer: A Tale of the Late American War.” Chapters IV and V contain a lifeboat drama, a sensational rescue, and several pirate attacks. The storytelling is lush and action-packed, providing a slice of mid-19th-century romanticism in the spirit of a writer like Herman Melville. “It was daybreak on the sea,” the chapter opens, “and a solitary yaw with two men was drifting many leagues from land, away to the eastward of Cape St. Roque.”

Later in the issue comes an un-credited portion of another serialized story called “The Infernal Box.” In it, a rich, powerful man notices from his opera box a new girl in the audience; he makes a bet with his wealthy buddies that he can seduce her. “In Paris exists a class of men who have made the art of seduction a perfect science. They attack a woman as a fortified palace,” the narrator says. “If pitiless, it is because they have not been pitied. They retaliate upon others the mortal blows which they have received. They not only seduce. They avenge themselves.”

The extent of Poe’s involvement in acquiring “The Infernal Box” is unclear, but it’s difficult not to see his hand in this story. Its twisted suspense reflects some of Poe’s well-known virtues as a writer. He’s been credited with inventing the genre of the detective story, and “The Infernal Box” moves like a procedural as the narrator patiently analyzes various possibilities and avenues towards his ultimate goal. Less charitably, Poe also had a dark obsession with women as victims. He once wrote that “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.” Poe’s mother died of tuberculosis when he was three, his step-mother died when he was 20, and he married his 13-year-old cousin, who died of tuberculosis herself 11 years later, when he was 27. The chapters of “The Infernal Box” contained in Burton’s September issue focus on a self-escalating pattern of male aggression, embarrassment, and fear.

Hopping across a few poems—including one titled, unsurprisingly, “The Dying Wife”—and another, duller maritime narrative, we finally arrive at “The Fall of the House of Usher.” “During the whole of a dull, dark, and soundless day in the autumn of the year, when the clouds hung oppressively low in the heavens, I had been passing alone, on horseback, through a singularly dreary tract of country,” Poe writes. From the opening plunge, it’s clear that we’re in the hands of a master, a writer who can quickly and powerfully render a scene and place the reader in it. The story is both manic in its approach and obsessively focused. Darker, more interesting, and more complex than “The Infernal Box,” the woman in this story is a victim—her brother accidentally buries her alive—but she’s also a threat. She comes back from the dead and, in bloodied robes, attacks her brother—frightening him to death and bringing the mansion crumbling down.

Poe’s now-iconic story is followed by an essay entitled “A Rummage in My Old Bureau,” in which a 90-year-old man goes through one of his old dressers, stopping at letters from old acquaintances, a boat whistle, and the “skull of a New Zealand warrior” given to him by his son. In its slow reminiscence over the mundanities of the past, the piece shares a lot in common with the contemporary autofiction of a writer like Karl Ove Knausgaard. Yet it, too, has strange register regarding women: the narrator spends just as much time reflecting on a silver chain given to him by a sailor as he does on the time he was out on a boat with his new wife and a spar hit her in the head, killing her.

Burton’s September issue concludes with a series of book reviews on ephemeral texts by publishers who have all since long-disappeared. Upon hiring Poe, Burton had disarmed him of his hatchet, the effect of which is on display in these largely uncritical reviews. He once warned Poe in a letter, “You must get rid of your avowed ill-feelings towards your brother authors—you see that I speak plainly—indeed, I cannot speak otherwise. Several of my friends, hearing of our connexion, have warned me of your uncalled-for severity in criticism.”

Not far into their partnership, disagreements over literary approach and business led to some nasty exchanges between Burton and Poe. “When you address me again, preserve, if you can, the dignity of a gentleman,” Poe wrote in a May 1840 letter. “If by accident you have taken it into your head that I am to be insulted with impunity I can only assume you are an ass.” There were editorial disputes, and Poe defensively perceived Burton to be accusing him of alcoholism, and bitterness over money once borrowed.

Poe left Burton’s in June 1840. The magazine was struggling, and Burton soon after started suspending payments to writers. A theater manager once wrote of Burton, “As an actor, Mr. W.E. Burton has no superior on the American Stage—but as a manager, his faults are, first, want of nerve to fight a losing battle; in success he is a great general, but in any sudden reverse, his first thought is not to maintain his position, but to retreat.” By the end of that year, Burton’s had ceased to exist.

We see in the saga of Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine two bullheaded creators with immense intelligence and talent participating in the minutiae of their cultural and economic moment. They built something that pretty quickly failed, but not before providing a platform for some moments of remarkable, if occasionally troubling, writing.

Poe’s influence—as an editor, and a popular writer in his own right—manages to bleed across this September issue, highlighting the brilliant parts of his work as well as the offensive or humdrum. He used Burton’s as a stage for himself—for his own tastes and sensibilities, and his own poems and stories—and the magazine lives on in memory primarily due to the fact that Poe once worked there.

William Burton would probably hate that.

The post Edgar Allan Poe, Editor and Original Hatchet Man appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Lyons Press Partners with History Channel on New Series

Lyons Press is partnering with A+E Networks to publish a series of illustrated titles based on the History channel’s “Breaking History” programs. The first volume, Breaking History: Vanished!: America’s Most Mysterious Kidnappings, Castaways, and the Forever Lost, will be published in October 2017.

The books will follow the format of the History television shows, which are currently broadcast to 96 million homes. Historians and non-fiction writers will present historical events from the viewpoint of breaking news, alongside color images, maps, and photographs. History.com contributor Sarah Pruitt will write the series debut.

The partnership with Lyons, which is an imprint of Globe Pequot, will add to the publisher’s existing catalog of history titles. In a press release, Globe Pequot publisher Jim Childs called the partnership, “a great way to bring History's programming to the printed page.”

A second volume, entitled Breaking History: Lost America! is slated for release in Spring 2018. It will examine unresolved mysteries and controversies surrounding historical movements and events in the U.S. from the collapse of Roanoke Colony to the demise of the Detroit bootleggers known as the Purple Gang.

Subsequent titles in the series will be announced at a later date.

The post Lyons Press Partners with History Channel on New Series appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Enemies of the State: A Memoir of Coming of Age in the Soviet Union

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, 1948.

Credit

From "The Girl From the Metropol Hotel"

THE GIRL FROM THE METROPOL HOTEL

Growing Up in Communist Russia

By Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Translated by Anna Summers

Illustrated. 149 pp. Penguin Books. Paper, $16.

Russian literature is replete with powerful memoirs of childhood: Tolstoy, Gorky, Nabokov, Mandelstam and Tsvetayeva all wrote movingly and insightfully about growing up. And yet, when one looks for texts about children’s lives after the Communist revolution, the bookshelf seems strangely empty. Where are the great memoirs of Soviet childhood? Perhaps the traditional narrative approach taken by Tolstoy or Nabokov cannot effectively depict the spare, hungry life of a child in a totalitarian state.

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s slender, fragmentary memoir, “The Girl From the Metropol Hotel,” is strangely much closer in tone and craft to Soviet absurdist poetry than it is to these classic memoirs. That poetry is exemplified by authors such as Daniil Kharms and Aleksander Vvedensky, known for their farcical depictions of early Soviet life in all its casual brutality. The reader feels the echo of such poems when Petrushevskaya’s younger self, a girl who’s been desperately hungry for most of her life, finds herself in possession of a fistful of silver coins. What does she do? She throws them into the courtyard, watching with a smile as dirty boys swarm to retrieve them, as each dropped coin “caused a new explosion of howling and fighting.” If this memoir of growing up on the streets of the Soviet Union follows a logic, it is the violent, chaotic logic of Soviet history itself.

As the girl from the Metropol Hotel, Petrushevskaya was born into an elite Bolshevik family in 1938, in the midst of great misfortune: Several family members were executed by Stalin’s firing squads. The family became “enemies to everyone,” Petrushevskaya writes, “to our neighbors, to the police, to the janitors, to the passers-by, to every resident of our courtyard of any age. We were not allowed to use the shared bathroom, to wash our clothes, and we didn’t have soap anyway. At the age of 9 I was unfamiliar with shoes, with handkerchiefs, with combs; I did not know what school or discipline was.”

Petrushevskaya’s young mother leaves her with her ill grandmother during World War II, and the lonely child wanders from street to street, from one short chapter to another, looking for food in the neighbor’s garbage. Her aunt brings home potato peels from the compost heap, which her grandmother bakes on their Primus stove. That’s dinner. Her grandmother’s consolation comes in the form of reading aloud from Gogol’s stories. When 9-year-old Ludmilla runs away, she survives street life by reciting those pages of Gogol by heart. “I didn’t beg by holding out a hand on street corners,” she writes, “I performed like Édith Piaf.”

The translator Anna Summers’s inspired introductory essay helps to present this book as a memoir of war, events therein echoing the misfortunes currently inflicted on other young girls from Ukraine to Syria and beyond. In this context, Petrushevskaya’s powerful memoir reminds us that, as Ingeborg Bachmann once wrote, “war is no longer declared, / it is continued.”

Like a stained-glass Chagall window, Petrushevskaya’s Soviet-era memoir creates a larger panorama out of tiny, vivid chapters, shattered fragments of different color and shape. She throws the misery of her daily life into relief through the use of fairy-tale metaphors familiar to fans of her fiction: At the end of a chapter about being mistreated by other children at the sanitarium, she writes: “The circle of animal faces had never crushed the girl; it remained behind, among the tall trees of the park, in the enchanted kingdom of wild berries.” Ultimately, the girl emerges not only uncrushed but one of Russia’s best, and most beloved, contemporary authors, which brings to mind Auden’s famous words about Yeats: “Mad Ireland hurt him into poetry.” This memoir shows us how Soviet life hurt Ludmilla Petrushevskaya into crystalline prose.

Continue reading the main story

The post Enemies of the State: A Memoir of Coming of Age in the Soviet Union appeared first on Art of Conversation.