Roy Miller's Blog, page 242

March 18, 2017

Staff Pick: ‘The Art of American Book Covers: 1875-1930’ by Richard Minsky

Among the products of the publishing business that PW editors see far more of, on a daily basis, than the civilian reader are book covers, even if they are only rarely a subject in PW. But rest assured, designers, we are all familiar with the never-ending task of conveying subject and content attractively, clearly, and accurately, and with the tropes and tics that inevitably arise. That’s why I like to keep a copy of The Art of American Book Covers: 1875-1930, by Richard Minsky, published by George Braziller, Inc., nearby on my shelves, since it furnishes some particularly striking examples of how a different era met the same challenges. Minsky focuses on stamped hardcovers, before the dominance of dust jackets, and on designs influenced by Victorian trends like William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement and the Western embrace of Eastern, particularly Japanese woodcut, art. Throughout, the covers chosen are elegantly simple, to the point of minimalism or even near-abstraction, favoring silhouettes and decorative patterns over the busier, more literal illustrations we’re now accustomed to. Minsky even includes a key to the monograms used by designers to sign their work (and notes that Houghton Mifflin advertised their 1887 catalog by announcing the famous designer hired but leaving the completed covers up to purchasers to discover). There’s an appealing element of mystery to these designs, which rarely announce exactly what content lies within, of course enhanced by the fact that many of the books are long out of print and forgotten. Minsky makes clear that these covers weren’t typical even of their own time, but they still might hold a good lesson for today.

The post Staff Pick: ‘The Art of American Book Covers: 1875-1930’ by Richard Minsky appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Weekly Round-Up: Pen Names and Pentameter

Every week our editors publish somewhere between 10 and 15 blog posts—but it can be hard to keep up amidst the busyness of everyday life. To make sure you never miss another post, we’ve created a new weekly round-up series. Each Saturday, find the previous week’s posts all in one place.

Add Your Vote

Who do you think is the best book villain of all time? Vote now in Arch Villain Madness: The Final Sixteen.

What’s in a Name?

When you’re an author, your name isn’t just your identity—it’s also a significant piece of your brand. To ensure your name is working for your brand, read and decide if a pen name is right for you.

Ever stumbled over using a contraction with a proper noun in your writing, as in “Brian’s a baseball fan”? This week, we remember Bill Walsh, copy editor at The Washington Post and expert grammarian, through his advice on Contractions With Proper Nouns.

Agents and Opportunities

This week’s new literary agent alert is for Damian McNicholl of the Jennifer De Chiara Literary Agency. He is looking for great nonfiction and fiction that appeals to a wide audience and makes people think, laugh, and sob.

As a new author, it can be hard to know what to expect—and how to survive. Prepare yourself for the world of publishing with 7 Things I’ve Learned So Far, by Tom Leveen. Then check out Tips for Surviving a Book Tour from a Debut Novelist.

Poetic Asides

For this week’s Wednesday Poetry Prompt, write a poem entitled “As (blank) as (blank,” replacing the blanks with your chosen words or phrases.

Meet Jaswinder Bolina, American poet and essayist, and check out a poem from his collection Phantom Camera.

This week’s Poetry Spotlight shines on Poetry@Tech, a poetry program offered through Georgia Tech in Atlanta, Georgia.

Do you know your poetry terms? Get a refresher with 37 Common Poetry Terms.

You might also like:

The post appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Machiavelli Runs Up Against the Borgias

Niccolò Machiavelli

Credit

Getty Images

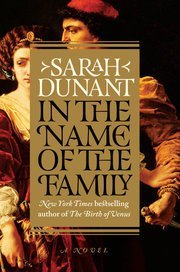

IN THE NAME OF THE FAMILY

By Sarah Dunant

429 pp. Random House. $28.

In her latest novel, Sarah Dunant returns to the Borgias, that flamboyant family of 15th-century clerics and cutthroats, a larger-than-life clan that includes Pope Alexander VI, also known as Rodrigo; his son Cesare, a reluctant cardinal turned conqueror; and the infamous Lucrezia, whose reputation Dunant has done much to restore. In Dunant’s view, Lucrezia isn’t nearly as bad as, say, Victor Hugo or Alexander Dumas led us to believe — or Donizetti in his opera. And historians now agree, having dismissed as gossip the notion of Lucrezia as a murderer with a love of poison.

To a degree, “In the Name of the Family” has less excitement than its predecessor, “Blood and Beauty,” in which Dunant followed the rise of Rodrigo as pontiff, describing his galvanic lust for attention, for women, for power, and his willingness to make use of his helpless daughter, who becomes a pawn in his machinations, forced to marry men who would advance her father’s worldly kingdom. To compensate, Dunant has added another character, Niccolò Machiavelli, author of “The Prince,” who provides us, at the outset, with a snapshot of the Italy of his time, a boot whose surface has been “discolored by the vicissitudes of history.” This is a reminder that the action will take place centuries before unification, that the Italy of the period is still a loose collection of city-states, each with its own internal tensions, its own rivals and potential invaders. In the midst of all this, the Borgias have risen, a family with a talent for conquest — just the sort of people to captivate Machiavelli, the master of expediency. It’s material that, in the hands of a gifted storyteller like Dunant, will captivate readers.

Dunant has written best-selling novels in the past. And in both her thrillers and her historical novels, she occasionally leans on the sort of ready-made language that merely carries this sort of story along. One gets any number of overly familiar descriptions, as when admirers of the pope “hang on his every word” or a bishop’s expression “is one of stone.” Elsewhere, a government official “throws up his hands in frustration” and a duke’s feelings are “shrouded in cold clouds of secrecy.” But more often than not, Dunant surprises us with fresh and inventive imagery, as when, near the end, we see the ailing pope in his bedchamber in late summer:

“He has a cramp in his left leg, his gut is grumbling and his farts are a long way from the scent of orange blossom. The sounds and smells of old men: Such things had been repugnant to him when he was young and he feels no differently now. He heaves himself over onto his other side, his stomach collapsing like a small landslip next to him.”

Machiavelli comes to the Borgias as a diplomatic envoy, bathing in the glow of Cesare’s ambitions and ruses. After meeting him, Machiavelli writes back to his superiors in Florence: “This lord is truly splendid and magnificent.” Indeed, “he arrives in one place before it is known that he left another.” Not surprisingly, Machiavelli’s Florentine handlers find his swooning less than helpful. “Less ‘opinion,’ ” they demand. “More facts.”

The character of Machiavelli is appealing, and I wished to see more of him. But Dunant wants to tell us everything she knows about the Borgias and their enemies, and she has an enviable command of this complex political scene, with its shifting alliances and subtle betrayals. It’s a world of “plots and counterplots, layer upon layer of deception, lurid tales of traitors hewn in half or tied back-to-back to chairs, blaming each other and sobbing for mercy as the garrote tightens around their throats.” Needless to say, “treachery is a disease of the age.”

Photo

As in previous novels like “Sacred Hearts,” Dunant has a special gift for attending to her female characters. This is obvious in the picture of Lucrezia that emerges as the pope’s daughter navigates the diplomatic entanglements wrought by her father and brother. Now she must deal with the prospect of a new husband, her third. Hardly a thing of beauty, Alfonso d’Este — heir to the Duchy of Ferrara — has “a heavy nose and thick lips,” and his massive hands are “mottled purple, like the surface of rotting meat.” The narrative sits up and preens whenever Lucrezia enters, and it’s a pleasure to watch her deal with a trying father-in-law, an unappealing husband and visits from her overbearing brother, whom the old duke describes as an “unscrupulous, ungodly, uncouth, whoring, warring bastard son of a Spanish interloper.” And that’s his nicer side.

This capacious if highly conventional historical novel glides on to its own dissolution as the lives of Rodrigo and Cesare unravel, the strings binding their empire loosen, their minds fray, their bodies weaken. Only Lucrezia seems to flourish, although we learn about this somewhat after-the-fact in the epilogue, narrated by Machiavelli in later life.

There may be more history in this novel than fiction, which lessens the emotional impact of an otherwise satisfying tale, impressive in its sweep and mastery of detail. I only wish that Dunant had managed to bring all her characters to life as ably as she has Lucrezia, who is perhaps the one indelible figure inhabiting this story.

Continue reading the main story

The post Machiavelli Runs Up Against the Borgias appeared first on Art of Conversation.

(Early) Spring Reading – The New York Times

Credit

Joon Mo Kang

Here in New York City, we had several days of baseball-appropriate weather in February. The famous cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C., are due to peak as early as they ever have. Spring — and spring books — are here.

In “The Songs of Trees,” David George Haskell travels to Japan, Jerusalem, New York City and elsewhere to closely observe the complicated relationships trees have with their environments, including humans.

Haskell is occasionally prone to a biological mysticism. “We cannot step outside life’s songs,” he writes in the preface. “This music made us; it is our nature.” But he also emphasizes when greenery is not touchy-feely. In the Amazon, he takes in impressive trees — about 50 meters tall — both from the ground and from up in their crowns. “If you slip or need to steady yourself, do not grab the nearest branch,” he writes. “Bark here is an armory of spikes, needles and graters.”

Lynda V. Mapes adopts a narrower lens but is equally ambitious in “Witness Tree,” which gets at sweeping ideas by looking at one century-old oak tree in Massachusetts. Among many other subjects — forest regeneration, acorn production, pollen records — Mapes has plenty to say about our early spring(s). “Climate change, the trees, streams, and puddles, and birds, bugs, and frogs, attest, is not a matter of opinion or belief,” she writes. “It is an observable fact.”

Quotable

“I often say that I want to write like Tupac rapped. I could listen to his album and within a few minutes, I could go from thinking deeply to laughing to crying to partying. And that’s what I want to do as a writer.” — Angie Thomas, author of “The Hate U Give,” in an interview with NPR

Stop The Presses

“The printing press has recorded and spread some of the greatest achievements of humankind. But remember, humankind is also full of idiots.” Those are two of the first sentences in “Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories From Book History,” by J.P. Romney and Rebecca Romney. Their work of history does chronicle some entertaining mistakes — like the 17th-century printer who produced a version of the Bible in which the Seventh Commandment read: “Thou shalt commit adultery.” But much of the book is devoted to the unusual rather than the erroneous. James Allen, for instance, was an American armed robber executed for his crimes in the 19th century. He wrote his memoir while awaiting execution, and requested that it be “bound in his own skin and delivered to the man who had helped capture him.” His will was done. Less gruesome stories are told about William Blake’s illuminated manuscripts and the feud that led to “the destruction of one of the world’s most beautiful fonts.”

Continue reading the main story

The post (Early) Spring Reading – The New York Times appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Paperback fighter: sales of physical books now outperform digital titles | Books

At the start of this decade publishers feared the death of the paperback. Britons abandoned bookshops at an alarming rate, seduced by e-readers and cheap digital books.

Even Jeff Bezos, the Amazon founder, was shocked by the speed of readers’ defection when Kindle downloads outsold hard copies on the website for the first time in 2011. “We had high hopes this would happen eventually, but we never imagined it would happen this quickly,” he said at the time.

But the ebook story has turned out to have a twist in the tale. Sales of physical books increased 4% in the UK last year while ebook sales shrank by the same amount. Glance around a busy train carriage and those passengers who aren’t on their phones are far more likely to have a paperback than a Kindle.

The e-reader itself has also turned out to have the shelf life of a two-star murder mystery. Smartphones and tablets last year overtook dedicated reading devices to become the most popular way to read an ebook, according to the research group Nielsen.

Michael Tamblyn, chief executive of Kobo, which makes e-readers and sells ebooks, including for WH Smith and Waterstones, reckons the decline is simply down to pricing. “We have seen ebook prices rise from traditional publishers and that does pull people away from digital and back to print.”

“Traditional publishers are setting the prices, which limits our ability as a retailer to discount or run price promotions,” he said. “One of the things that attracts people to ebooks is their affordability and people’s ability to take that pound they have for reading and stretch it further. Previously a book that a publisher would have published at £10.99 we could have sold for £7.99. What we like to see is a nice healthy distance between a print book and an ebook. It’s usually still the case but often isn’t as wide as we would like it to be.”

The average price paid for an ebook increased 7% to £4.15 in 2016, while the price of a hard copy increased 3% to £7.42.

The shift in ebook pricing reflects a change in the contractual terms agreed between Amazon, which controls up to 90% of the UK ebook market, and the major publishing houses. As a result it is now sometimes cheaper to buy the physical copy of a new title on Amazon than the Kindle download. Of the 16 books on the longlist for the Baileys women’s prize for fiction seven are either cheaper in print form or roughly the same price.

Glance around a train and passengers who aren’t on their phones are far more likely to have a paperback than a Kindle. Photograph: Roy Botterell/Getty Images

Another reason why digital book sales declined last year is because cookery and humour are simply better in print – and last year’s bestseller lists were populated by books by the fitness guru Joe Wicks, the Ladybird Books for Grown-ups series and Enid Blyton parodies.

“When we first started the business there was an expectation we would see 50% print/digital within five years [from 2012],” said Tamblyn. “Instead the ebook market has been plateauing in the 25-30% range.”

Ebooks perform best, he said, with “blockbuster fiction bestsellers and young adult crossover books like Hunger Games and Insurgent”.

The UK reached peak e-reader in 2014, when a quarter of UK book buyers owned one. Three years on that figure is back to only just over one-fifth as Britons have swapped their e-reading on to phones and tablets. Waterstones stopped selling the Kindle two years ago because they were “getting virtually no sales”.

Despite the digital market’s rapid wax and wane, the industry does not expect e-readers to join MP3 and MiniDisc players in the tech dustbin. The devices, said Tamblyn, were still prized by prolific readers – a group that is predominantly female and over 45, and devours romance and crime novels.

Douglas McCabe, a media expert at the research firm Enders, reckons e-readers will continue to fall out of favour but that older readers would remain fans, not least because of the appeal of being able to “make the font bigger”.

The revival of print means the publishing industry is no longer being consumed by the battle between the two channels. “The real focus for the industry as a whole is how we preserve time for reading,” said Tamblyn.

“People are more than willing to sit down for five hours and watch six episodes of The Walking Dead. We are in a digital arena fighting for that same customer as Netflix or Facebook. For all of us the fight really is around attention and our ability to bring it back to reading.”

The post Paperback fighter: sales of physical books now outperform digital titles | Books appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Tracking Unit Print Sales for Week Ending March 12, 2017

Unit sales of print books were 5% higher in the week ended Mar. 12, 2017, than in the comparable week in 2016, at outlets that report to NPD BookScan. The adult fiction segment had the strongest performance, with units up 10% from the week ended Mar. 13, 2016. The increase in adult fiction was driven by three new releases landing among the top 10 category bestsellers, including two novels that took the first two spots: Danielle Steel’s latest hardcover, Dangerous Games, was #1, selling more than 27,000 copies, while the mass market paperback of The Obsession by Nora Roberts was in second place, selling more than 22,000 copies. Print units were up 6% in the adult nonfiction category, helped by good performances by two books in their second weeks: Unshakeable by Tony Robbins rose to the top spot on the category bestseller list, selling nearly 40,000 copies. And The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild jumped to #3 on the category list, selling slightly more than 28,000 copies. Unit sales in the juvenile fiction segment increased 2% from 2016, despite a general decline in sales of Dr. Seuss books from the prior week. Four Seuss titles took the first four spots on the category bestseller list, selling a total of about 90,000 copies. Juvenile nonfiction unit sales in the week were 3% higher than in 2016, with little movement at the top of the category bestseller list. In terms of formats, mass market paperback had a rare increase in sales, with units up 2% in the week over 2016. Despite the gain, mass market unit sales were down 7% in the first 10 weeks of 2017 from the same period last year.

Unit Sales of Print Books by Channel

Mar. 13, 2016

Mar. 12, 2017*

Chge Week

Chge YTD

Total

11,892

12,502

5%

0.4%

Mass Merch./Other

2,123

1,909

-10%

-11%

Retail & Club

9,769

10,592

8%

3%

Unit Sales of Print Books by Category

Mar. 13, 2016

Mar. 12, 2017*

Chge Week

Chge YTD

Adult Nonfiction

4,831

5,119

6%

1%

Adult Fiction

2,317

2,551

10%

2%

Juvenile Nonfiction

1,092

1,129

3%

-1%

Juvenile Fiction

3,317

3,373

2%

-2%

Unit Sales of Print Books by Format

Mar. 13, 2016

Mar. 12, 2017*

Chge Week

Chge YTD

Hardcover

3,250

3,480

7%

2%

Trade Paperback

6,503

6,871

5%

0.3%

Mass Market Paperback

1,071

1,089

2%

-7%

Board Books

795

760

-4%

1%

Audio

61

61

0%

-2%

A version of this article appeared in the 03/20/2017 issue of Publishers Weekly under the headline: The Weekly Scorecard

The post Tracking Unit Print Sales for Week Ending March 12, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

March 17, 2017

Editors’ Tips on Revising Your Manuscript and Query Letter

Click here to listen to the webinar recording.

In this free live webinar, five top Reedsy editors will share their ultimate revision tips and give you the inside scoop on querying agents. If you’re looking to secure a book deal, you must first know how to write the perfect query letter, when it’s best to submit that query, and how to polish your manuscript to best appeal to agents and publishers. This webinar is the perfect opportunity to learn directly from publishing experts.

Reedsy co-founder Ricardo Fayet will be joined by a panel of esteemed editors, agents, and independent publishers, all from the Reedsy marketplace:

Scott Pack, former HarperCollins Publisher

Katrina Diaz, former Simon & Schuster Editor

Erin Young, literary agent at Dystel, Goderich & Bourret LLC

Jim Thomas, former Editorial Director at Random House

Constance Renfrow, Lead Editor at Three Rooms Press

The webinar will include an extensive Q&A session at the end, where you will be able to get all your questions answered by our panel of experts.

ABOUT THE INSTRUCTOR:

Ricardo Fayet is the co-founder of Reedsy, a global network that connects authors and publishers with top editorial, design, marketing and ghostwriting talent. A technology and startup enthusiast, he likes to imagine how small players will build the future of publishing. He is behind the launch of Reedsy’s latest initiative, Reedsy Learning , a series of free mini-courses on writing, publishing, and marketing, taught by Reedsy’s best professionals and delivered to your inbox each day.

Click here to listen to the webinar recording.

You might also like:

The post Editors’ Tips on Revising Your Manuscript and Query Letter appeared first on Art of Conversation.

‘The Pages of the Sea’: A Walcott Sampler

Whatever else we learned

at school, like solemn Afro-Greeks eager for grades,

of Helen and the shades

of borrowed ancestors,

there are no rites

for those who have returned,

only, when her looms fade,

drilled in our skulls, the doom-

surge-haunted nights,

only this well-known passage

under the coconuts’ salt-rusted

swords, these rotted

leathery sea-grape leaves,

the seacrabs’ brittle helmets, and

this barbecue of branches, like the ribs

of sacrificial oxen on scorched sand;

only this fish-gut-reeking beach

whose frigates tack like buzzards overhead,

whose spindly, sugar-headed children race

pelting up from the shallows

because your clothes,

your posture

seem a tourist’s.

They swarm like flies

Round your heart’s sore.

From ‘Another Life’ (1973)

So, I shall repeat myself,

prayer, same prayer, towards fire, same fire,

as the sun repeats itself and the thundering waters

for what else is there

but books, books and the sea,

verandahs and the pages of the sea,

to write of the wind and the memory of wind-whipped hair

in the sun, the colour of fire?

From ‘The Star-Apple Kingdom’ (1979)

One morning the Caribbean was cut up

by seven prime ministers who bought the sea in bolts—

one thousand miles of aquamarine with lace trimmings,

one million yards of lime-colored silk,

one mile of violet, leagues of cerulean satin—

who sold it at a markup to the conglomerates,

the same conglomerates who had rented the water spouts

for ninety-nine years in exchange for fifty ships,

who retailed it in turn to the ministers

with only one bank account, who then resold it

in ads for the Caribbean Economic Community,

till everyone owned a little piece of the sea,

from which some made saris, some made bandannas;

the rest was offered on trays to white cruise ships

taller than the post office; then the dogfights

began in the cabinets as to who had first sold

the archipelago for this chain store of islands.

From ‘The Prodigal’ (2004)

Since I am what I am, how was I made?

To ascribe complexion to the intellect

is not an insult, since it takes its plaid

like the invaluable lizard from its background,

and if our work is piebald mimicry

then virtue lies in its variety

to be adept. On the warm stones of Florence

I subtly alter to a Florentine

till the sun passes, in London

I am pieced by fog, and shaken from reflection

in Venice, a printed page in the sun

on which a cabbage-white unfolds, a bookmark.

To break through veils like spiders’ webs,

crack carapaces like a day-moth and achieve

a clarified frenzy and feel the blood settle

like a brown afternoon stream in River Doree

is what I pulsed for in my brain and wrist

for the drifting benediction of a drizzle

drying on this page like asphalt, for peace that passes

like a changing cloud, to a hawk’s slow pivot.

Continue reading the main story

The post ‘The Pages of the Sea’: A Walcott Sampler appeared first on Art of Conversation.

The Guardian view on Brexit and publishing: a hardcore problem | Editorial | Opinion

The mood at this week’s London book fair appeared upbeat, with hotly contested auctions leading to the return of the six-figure publishing deal. Musicians did particularly well, with Pulp’s Jarvis Cocker, Suede’s Brett Anderson and drum’n’bass pioneer Goldie leading the way. Rumours of the death of literary fiction appear exaggerated. A collection of short stories, traditionally regarded as commercial suicide, earned Orange prize winner Lionel Shriver a place at the top of the sales league. The razzmatazz of such deals, however, is only part of the story of the modern books industry.

Publishing is a commercial enterprise, and like all businesses it thrives in an atmosphere of certainty that ceased to exist the day the UK voted for Brexit. In a heated opening debate on the impact of the decision to leave the European Union, a succession of leading publishers rounded on the prime minister, Theresa May, for “playing with people’s lives” in her negotiations. The government emissary parried criticism by insisting that ministers were “at the fat end of the funnel”, sucking up information from businesses to understand how best to represent them. The information came fast and furiously, with much of the concern about freedom of movement. We have heard a lot about the fears of the university sector about the drain on research and student income, but we know less about the impact on the more cultural corners of publishing.

Children’s publisher DK reported that a sixth of the 500 staff at its London headquarters were European nationals, and since the referendum it had been struggling to recruit. HarperCollins said that “a significant proportion” of its Scottish distribution centre workers were from eastern Europe and had been leaving in droves. Faced with the perfect storm of a weak pound, which reduced the money they could send home to their families, and uncertainty about whether they would be able to stay, they were voting with their feet. These are the issues we need to consider. The book fair has reaffirmed the vibrancy – and economic value – of a global intellectual culture. If we want to remain part of it, the government needs to do more than sit at the fat end of that funnel. As Jarvis Cocker might say, this is hardcore and it’s everybody’s problem.

The post The Guardian view on Brexit and publishing: a hardcore problem | Editorial | Opinion appeared first on Art of Conversation.

15 Great Irish Writers You’ve Probably Never Read (But Should)

It’s St. Patrick’s Day, which means that many in the US will be celebrating their Irish heritage with a pint or two—or just, you know, celebrating with a pint or two (or seventeen). But if you’re not committed to wearing a horrifying shade of green and getting completely hammered tonight, might I suggest celebrating the holiday in style with a little contemporary Irish literature instead? Sure, if you’ve found your way to this space, you’ve likely been reading lots of contemporary Irish writers already—Eimear McBride, Kevin Barry, Tana French, Emma Donoghue, etc.—but there are plenty that, despite the shared language, haven’t quite gotten their due stateside. But honestly? We’re missing out. As Mike McCormack explained in an interview with Stephanie Boland at New Statesman:

In Ireland, our pinnacle, our Mount Rushmore, is the Father, Son and Holy Ghost: James Joyce, Flann O’Brien and Samuel Beckett. And it feels like we’re digesting their legacy. I don’t know if it’s something about being able to see them clearly now, but people are no longer afraid to name-check the three masters. My generation were a bit wary of picking up the challenge those old fellows had laid down for us. Now I see it not as a challenge, but a license. Beckett and Joyce and Flann are giving me the quest: go forth and experiment. A younger generation of writers has twigged that a lot faster. This is a really exciting time: for the first time in my lifetime, there’s been a rejuvenation of the experimental pulse in Irish fiction.

To put your own finger on that pulse—and perhaps spend the Feast of Saint Patrick actually celebrating the culture in question—check out some of the writers below.

Article continues after advertisement

Mike McCormack

Despite being “disgracefully neglected,” McCormack is a star of Irish experimental literature—anyone interested in innovative work should already be reading him. Solar Bones—McCormack’s third novel and fifth book—was awarded the prestigious 2016 Goldsmith Prize, given “to reward fiction that breaks the mould or extends the possibilities of the novel form”—appropriate, since Solar Bones is a 224-page novel written in a single sentence, the rhythmic pattern of a 49-year-old civil engineer unraveling the story of his life. Solar Bones will be republished in the US by Soho Press in September, which will hopefully get his work out to more Americans.

Sara Baume

In her first novel, Spill Simmer Falter Wither—which was shortlisted for the Costa first novel award and won an Irish book award for Best Newcomer—a middle-aged, misanthropic outcast develops a relationship with a one-eyed dog, whom he names One Eye, and with whom he goes on the lam, and with whom, increasingly, he speaks. In the Irish Times, Joseph O’Connor gushed, “This is a novel bursting with brio, braggadocio and bite. Again and again it wows you with its ambition, its implication, the more forceful for never being italicized, that simple words from our frail and brittle English language, placed quietly in order, with assiduous care, can do almost anything at all.” Baume’s second novel, A Line Made by Walking came out in the UK in February and is due to hit American shelves this April.

Colin Barrett

It’s rare to see a writer this decorated be so under-read—although, to be fair it’s also rare to see a writer be this decorated for a single short story collection. In 2014, Barrett’s Young Skins won the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award, the Guardian First Book Award, and the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, and after the collection was published in the US in 2015, it was chosen as a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 Honoree. Lyrical, rabid, and desolate, this is writing to watch.

Lisa McInerney

Once known primarily for her blog Arse End of Ireland and her Sweary Lady persona, McInerney’s debut novel fully established her as the exciting new bard of the Irish working class. The Glorious Heresies is a darkly comic story about murder, drugs, sex and life in the terrible, but yes, also glorious Cork underbelly. The novel was awarded the Desmond Elliott Prize and the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2016 (it will be the last winner of the current incarnation of the latter, it turns out), and is slated to be produced as a television show, so get reading now.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa

Ní Ghríofa is a bilingual poet, writing in both Irish and English. Her English-language debut Clasp was shortlisted for the Irish Times Poetry Now Award and awarded the Michael Hartnett Award and the Rooney Prize in 2016. Her poems have appeared in many journals, including Poetry, where you can find her amazing “While Bleeding,” which begins:

In a vintage boutique on Sullivan’s Quay,

I lift a winter coat with narrow bodice, neat lapels,

a fallen hem. It is far too expensive for me,

but the handwritten label

[1915]

brings it to my chest in armfuls of red.

In that year, someone drew a blade

through a bolt of fabric and stitched

this coat into being. I carry it

to the dressing room, slip my arms in.

Silk lining spills against my skin.

Claire Kilroy

Kilroy is the author of four novels—All Summer (a winner, like several others on this list, of the Rooney Prize), Tenderwire, All Names Have Been Changed, and The Devil I Know—but she still isn’t the household name she should be in the US. John Boyne described her as “the literary love-child of Jennifer Johnston and John Banville, reflecting the Anglo-Irish aristocratic concerns of the former with the incomparable linguistic precision of the latter. In time, she will certainly earn her place in their exalted company.” Let’s hope.

Marina Carr

Widely acknowledged as of Ireland’s best playwrights, and yet mostly unknown in the US, Carr is a wild, transgressive feminist voice in contemporary theater. She has been writing plays since the early 90s, and first gained wide renown with 1994’s The Mai, which won the Dublin Theatre Festival Best New Irish Play award. She hasn’t stopped accumulating praise and prizes since. In fact, just this month, she was awarded a $165,000 Windham-Campbell Prize. Of her work, the organizers wrote, “Like its successors Portia Coughlin (1996) and By the Bog of Cats (1998), The Mai doesn’t so much adapt as reinvent its source material, finding an ancient darkness in the hills and valleys of contemporary rural Ireland. Carr’s persistent focus in both the “Midland Trilogy” and her other work is female experience in its most mythic and paradoxical aspects: the power and vulnerability it embodies, the desire and disgust it provokes.”

Belinda McKeon

McKeon’s first novel, Solace, won the 2011 Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize, and her second, Tender—the story of a relationship that turns obsessive, in which the prose mirrors the mind of the protagonist as she slowly unwinds, which Catherine O’Flynn called an “immersive, unflinching yet humane portrait” of a besotted woman—was one of our favorite books of last year. She’s also a strong advocate for women’s rights, which never hurts.

Keith Ridgway

Ridgeway is the author of four novels and two short story collections. Scarlett Thomas called his most recent novel—the dreamlike, unsettling Hawthorn & Child, published in the US by New Directions in 2013—”breathtakingly unpredictable.” As Ian Rankin described it: “it begins as a police procedural, then spins outwards, never quite coming back to explain the mystery. Along the way we learn that a secret cabal of wild animals may underpin life in contemporary London, we hang out at art exhibitions, visit an orgy at a gay sauna, and wallow in gorgeous (if unsettling) writing. A novel or a series of loosely connected short stories? I don’t really care. Whatever it is, it’s great.” That “whatever it is, it’s great” is a sign: this is the cutting edge of literature, where no one knows which way is up.

Claire-Louise Bennett

Okay, you may have heard of Bennett, on account of the acclaim her debut, Pond, has gotten in certain literary circles recently, but there’s really no leaving her off a list of exciting contemporary Irish writers, so here we are. She won the inaugural White Review fiction prize for “ambitious, imaginative and innovative” prose in 2013, and Pond came out in Ireland in 2015 and in the U.S. this past summer, prompting lots of luminous praise, including from Jia Tolento, who called it “a work of fiction that will make you feel pleasantly insane,” which as far as I’m concerned is about the best recommendation any book and/or writer could ever receive.

Gavin Corbett

In The Guardian, Matthew Adams called Corbett “one of the most inventive and beguiling writers of contemporary Irish fiction,” and described his second novel, This is the Way, as “unconventional, associative and piecemeal… what kept the reader tied to the page was not the scant plot (Corbett regards plot as something of a distraction), but the strange beauty of Anthony’s voice. Here was a way of speaking that was spare, restrained, distortedly lyrical, full of anxious repetitions and hesitant tics, and almost overwhelming in its cumulative force.” His most recent novel, Green Glowing Skull, only pushes the boundaries further—but has not yet been published in America.

Danielle McLaughlin

As our own Managing Editor Emily Firetog put it, “The best Irish writers are short story writers, and the best Irish short story writers—for at least the last decade—have first been published by the small, independent press The Stinging Fly (my former employer; so I’m biased—whatevs).” Danielle McLaughlin’s collection Dinosaurs on Other Planets, first published in Ireland by said independent press in 2015, came out in the US this past summer, bringing a sharp new eye to stories about everyday life.

Donal Ryan

Ryan’s first novel The Spinning Heart won the Guardian First Book Award in 2013 and was also longlisted for the Booker Prize that year—some feat for a debut novel. Of his 2015 collection A Slanting of the Sun, Sara Baume (you may recognize this name if you’ve gotten this far) wrote, “These are plain-speaking stories, and in spite of the pervasive woe, this plain speech lends itself to blunt, bleak, brilliant humour. The droll jokes Ryan draws out of poetic adversity are what save A Slanting of the Sun from sentimentality. He also occasionally, astutely, extrapolates material from the national news, creating mouthpieces for those insufficiently represented by headlines….Each unit of language has been scrupulously positioned, though the overall effect is of effortlessness.” Exactly the kind of writing we need right now, if you ask me.

Mia Gallagher

Gallagher published her first novel, HellFire, in 2006, and it took her a full twelve years to write a second (dear math nerds: she started the second before the first came out, unless we’re in the future). Claire Kilroy (another writer from our list!) described her in the Irish Times as “a writer with an artist’s imagination. It advances though experiment. Her technique, to no small extent, is to present artefacts and images, much as a visual artist might, and to allow the audience to take from them what it will. Her characters are divided into those who can see the true natures of the people around them, and those who cannot—who cannot see even their own natures.” Of that finally released novel, Beautiful Pictures of the Lost Homeland, Kilroy writes that it “is challenging, it is brave, it is original, it is flawed, it is moving, it is fascinating. It is art.”

Paul Lynch

Lynch is an acclaimed film critic who also happens to write novels—novels that are particularly adored by the French, for some reason. Lynch’s work has won the Prix Libr’à Nous for Best Foreign Novel and has been a finalist for the Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger (Best Foreign Book Prize). He has won the Prix des Lecteurs Privat, and has been nominated for France’s Prix Femina, the Prix du Premier Roman (First Novel Prize) and the Prix du Roman Fnac (Fnac Novel Prize). His debut, Red Sky in Morning, was also a B&N Discover pick. NPR’s Alan Cheuse heralded his most recent novel, The Black Snow, for its “striking language, located somewhere between that of Irish Nobel poet Seamus Heaney and our own Cormac McCarthy.”

The post 15 Great Irish Writers You’ve Probably Never Read (But Should) appeared first on Art of Conversation.