Roy Miller's Blog, page 179

May 26, 2017

Publishing’s Bright Future (Really!)

This content was originally published by on 26 May 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Courtney Maum, humorist and author of the satirical novel ‘Touch,’ mines her history working as a trend forecaster to predict a coming boom in books.

Source link

The post Publishing’s Bright Future (Really!) appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Arcadia and History Press Acquire Palmetto, Launch Vertel

This content was originally published by on 26 May 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Arcadia Publishing and The History Press, publishers of books on local and regional history and interests, have acquired publishing services company Palmetto Publishing Group. With the acquisition, they have also launched a new “hybrid” imprint, Vertel.

PPG, which based in Charleston, S.C., will continue to be overseen by its founder, Michael Shannon II. Since PPG works with indie authors who are self-publishing, taking no royalties, the company does not have a backlist. It was the services that PPG offered which were of interest to Arcadia. As Shannon put it: “When Arcadia purchased Palmetto, they were not purchasing titles, they were purchasing a service-based publisher in an emerging market.”

While PPG publishes books of many stripes, Vertel, a “local, regional hybrid publishing division” will remain in Arcadia and History Press’s wheelhouse, Shannon said. The imprint will operate as something of a farm team for the group, with titles that, according to Arcadia, “show promise” eligible to be published as part of Arcadia or History Press’s catalogs.

“If we find books that are submitted to Vertel…but could fit with Arcadia or the History Press, they’re going to get automatically moved up,” Shannon said.] If they fit with neither—that is, if the book is, say, a fantasy, rather than a historical or regional title—PPG would publish the book.

Richard Joseph, Arcadia’s CEO, elaborated how Vertel will work. “These are titles that do not fit into our current publishing model due to the population or local retail climate,” he said. “Instead of sending the authors away, we want to continue to provide them with the highest quality product, customer service and help preserve worthy pieces of history by using an alternative model.”

The post Arcadia and History Press Acquire Palmetto, Launch Vertel appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Denis Johnson, Author Who Wrote ‘Jesus’ Son,’ Dies At 67 : NPR

This content was originally published by Lynn Neary on 26 May 2017 | 8:32 pm.

Source link

Denis Johnson was best known for his 1992 short story collection Jesus’ Son. He won the 2007 National Book Award for the novel, Tree of Smoke. Johnson died Thursday at age 67.

ARI SHAPIRO, HOST:

The literary world is mourning the death of a man who has been called one of the greatest writers of his generation. Denis Johnson won the National Book Award and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. He died of cancer on Wednesday at the age of 67. NPR’s Lynn Neary has this remembrance.

LYNN NEARY, BYLINE: Johnson, says Farrar, Straus and Giroux publisher Jonathan Galassi, is a writer’s writer. Galassi worked with Johnson on some of his best-known books – his story collection “Jesus’ Son,” his Vietnam War novel “Tree Of Smoke” which won the National Book Award and his novella “Train Dreams” which was a finalist for the Pulitzer. Johnson may have gotten the most attention for his prose, Galassi says, but he wrote with the empathy of a poet.

JONATHAN GALASSI: He started out as a poet, and then he started writing novels. And I remember him once saying, well, I can dream these novels up in a day, but it takes me months to write them.

NEARY: Galassi says Johnson was perhaps the most original writer of his generation. His work is infused with a hallucinatory quality, born out of his experiences in the 1960s and ’70s.

GALASSI: In his early phase of life, those hallucinations were enhanced by controlled substances which were part of the magic and the horror of his imagination.

NEARY: Johnson recovered from drug addiction in the late 1970s. But in 1991, he told WHYY’s Fresh Air that he held onto some of the insights he had gained during his time on drugs.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED BROADCAST)

DENIS JOHNSON: The world is very poetic as I experienced it. You know, you can just open a door, and there’ll be a world of fire and chaos on the other side. And you can shut that door and open another, and you know, all is sweetness and light. And I think that’s something I experienced by messing up my head a lot, and it’s something that stayed with me. And I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad perception to have.

NEARY: Johnson was able to balance violence with transcendence in his work. His writing was not biographical, says publisher Jonathan Galassi, but he drew deeply from his own experiences.

GALASSI: He has experienced the intensity, the depth, the despair, the direct hit of life in similar ways. And I think he’s very, very touched by it, destroyed by it. There’s something very religious about Denis’ work, I think.

NEARY: Galassi says he’s been touched by the large number of people who have contacted him since news of Denis Johnson’s death has spread, a tribute, he says, to how important Johnson was to so many. Lynn Neary, NPR News, Washington.

(SOUNDBITE OF LOS CAMPESINOS SONG, “YOU! ME! DANCING!”)

Copyright © 2017 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by Verb8tm, Inc., an NPR contractor, and produced using a proprietary transcription process developed with NPR. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

The post Denis Johnson, Author Who Wrote ‘Jesus’ Son,’ Dies At 67 : NPR appeared first on Art of Conversation.

The Eyes Have It: The Curious Use of Eyes in Fiction

This content was originally published by Guest Column on 26 May 2017 | 6:30 pm.

Source link

Upon my return to my writers’ group, I read a passage from my upcoming middle-grade novel, Almost Paradise, in which the main character, Ruby Clyde, asks a perfectly logical question and the Catfish rolls his eyes:

“Ruby Clyde,” Catfish rolled his eyes, “sometimes I think you are as dumb as a box of rocks.”

Every member of my writers’ group stood up and howled. “Nooooo!”

Apparently, in my absence the group had engaged in many lively debates about the use and abuse of eyes in fiction. Eyes are marvelous organs of expression but, really, how much does it add to a character when their eyes carry the entire weight of characterization? Is there no other moving part on the face? The eyes may be the windows to the soul (a phrase attributed to Shakespeare, the Bible, and English Proverbs) but unless we are careful, poor use of eyes may be windows to a complete lack of imagination.

This guest post is by Corabel Shofner. Shofner is a wife, mother, attorney, and author. She graduated from Columbia University with a degree in English literature and was on Law Review at Vanderbilt University School of Law. Her shorter work has appeared or is forthcoming in Willow Review, Word Riot, Habersham Review, Hawai’i Review, Sou’wester, South Carolina Review, South Dakota Review, and Xavier Review. Her middle grade novel, ALMOST PARADISE, will be released in July 2017.

This guest post is by Corabel Shofner. Shofner is a wife, mother, attorney, and author. She graduated from Columbia University with a degree in English literature and was on Law Review at Vanderbilt University School of Law. Her shorter work has appeared or is forthcoming in Willow Review, Word Riot, Habersham Review, Hawai’i Review, Sou’wester, South Carolina Review, South Dakota Review, and Xavier Review. Her middle grade novel, ALMOST PARADISE, will be released in July 2017.

Fictional eyes have been known to roll, lock, squint, narrow, bug, ogle, widen, dilate, sneak, leak, tear up, brim over, moisten, glisten, sparkle, get behind veils, show their whites, get cold as stone, throw themselves around, get cast to heaven, go “eye ball to eye ball”, and get dropped.

Some eyes have even dropped into laps. (Now what would they do there?)

[New Agent Alerts: Click here to find agents who are currently seeking writers]

After writers’ group dispersed, the e-mails flew:

I’m willing to forgive lots of things this author has eyes doing, like rolling and moving across her body, but when they fall into his lap, as they just did in this book, that’s just too much. How will he ever get them back into their sockets? (Rita)

Rolling your eyes is okay, I think, though it’s kind of a cliché. One thing [this author] does pretty often is have her characters’ eyes “narrow.” That can be pretty effective. But having eyes on his lap is just beyond the beyond. The image it projects is terrible. Quick, get them off his lap and back where they belong. They might slip down between his legs, and then what would he do? (Rita)

I think when it’s blatantly stupid (and descriptive), like “casting your eyes to the heavens,” that makes sense. But we can’t use a common expression like “rolling your eyes?” I think we’re being too literal with that one. (Shannon)

And eventually the subject opened up to include all bodily functions (from our doctor, of course.)

An editor once told me that body parts can’t act on their own; a character must make them act. However, that may not always be true: “Doug’s pulse sped up when the shapely girl approached him.” Did Doug make it accelerate or did it just take off on its own? (Rick)

If you need to use eyes in a story reach for the stars. In The Accidental Tourist, Muriel Pritchett has—“eyes like caraway seeds.” This is less a description of poor Muriel’s eyes than it is a reflection of Macon’s poor opinion of her. In The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison breaks our heart with a young girl’s wish to have blue eyes. Shakespeare gives us lover’s eyes that are powerful enough to “gaze an eagle blind.” Kurt Vonnegut goes out on a limb when he created little green folks, shaped like toilet plungers, topped by a hand with an eye, where he carefully describes eyes to show people’s state of mind—before and after the trauma of the concentration camp. And finally, Elie Wiesel, himself, looks in the mirror and sees the eyes of a corpse looking back at him.

By all means remove any thin reference to eyes, but should you try another—an eye for an eye? Sure, if the replacement is better. A lazy eye drags the story down but a complex eye lifts the story up. If your eyes aren’t working for the story, leave them alone. And for goodness sake, if eyes fall into a lap please just leave them there.

90 Days to Your Novel is an inspiring

writing

90 Days to Your Novel is an inspiring

writing

manual that will be your push, your deadline, and your

spark to finally, in three short months, complete that

first

draft of your novel. Order it now in our shop for a discount.

There Are No Rules is run by the editors of Writer’s Digest, featuring posts by our editors, guest contributors and more.

You might also like:

The post The Eyes Have It: The Curious Use of Eyes in Fiction appeared first on Art of Conversation.

New and Noteworthy Books on Military History, from Afghanistan to Waterloo

This content was originally published by THOMAS E. RICKS on 26 May 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Inside this very good fat book is an excellent thin book trying to get out. That’s more a criticism of the Oxford University Press than of the author, because what this book needed was an editor with a strong hand. At 670 pages, it is just too damn long. It contains sections that wax encyclopedic without any evident connection to the book’s core themes. For example, we are subjected to seemingly everything Nolan knows about the Crimean War, like the fact that the efforts of Florence Nightingale, the pioneer of modern nursing, were at first rebuffed by some British officers. We get a deep dive into the Franco-Prussian War, but oddly almost nothing on the American Civil War that preceded it. Asia goes unmentioned before the 20th century. The chapter titles are opaque, more like symbolic poetry than guideposts for the book.

Continue reading the main story

On the other hand, a book has to be really thought-provoking to have so many problems and still be so fascinating. I cannot remember reading anything in the last few years that has made me reconsider so many basic questions — What wins wars? What is the most illuminating way to relate military history? Most important, is our own military too focused on battles and insufficiently attentive to what is required to win wars? In other words, are our generals flailing because they try to substitute battlefield skill for strategic understanding? (I think they are.)

Ultimately, Nolan is persuasive that too much attention has been paid to battles. Even for that great genius of warfare, Napoleon, he argues — credibly — that the slow bleed of guerrilla war in Spain did much more than any battle to bring about his defeat. By the time of Waterloo, he insists, France was a spent force. And if Napoleon hadn’t been finished off there, he would have been at his next battle, or the one after that. So much for perhaps the most famously decisive battle in history.

Photo

“They avail themselves”: Goya’s “Disasters of War” No. 16.

Credit

Francisco Goya/Barney Burstein, via Corbis — VCG, via Getty Images

THUNDER IN THE MOUNTAINS: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War (Norton, $29.95) is almost the opposite kind of history book. In this far more traditional work, Daniel J. Sharfstein, a Vanderbilt University law and history professor, offers a brisk narrative of one of the last major collisions between Native Americans and white America. His two main characters are complex and compelling — Chief Joseph, a thoughtful, powerful speaker who spent years trying to find a way for his people to live alongside American settlers, and General O. O. Howard, a moralistic liberal Army general whose fate it was to crush Joseph’s small Nez Percé tribe.

Continue reading the main story

In the summer of 1877 it became clear that Joseph’s peaceable dream of coexistence was not possible. Deciding they would have no more to do with the whites, the Nez Percé set off on a trek from their homeland, which lay in the area where Oregon, Idaho and Washington meet. They eventually turned north, crossing at one point through the Yellowstone National Park, which had been established five years earlier. Howard’s soldiers, pursuing the tribe, enjoyed that park, Sharfstein notes, catching trout in the mountain rivers and poaching them in its geysers.

Continue reading the main story

The tribe’s thousand-mile retreat ended not far from the Canadian border, where it was finally surrounded by Army forces. Joseph famously stated there, “From where the sun now stands I will fight no more.” Less well known is the speech he gave in Washington, D.C., a few years later: “If the white man wants to live in peace with the Indian, he can live in peace. There need be no trouble. Treat all men alike. Give them all the same law. Give them all an even chance to live and grow. … Let me be a free man … and I will obey every law, or submit to the penalty.”

Continue reading the main story

Despite its stuffy academic title, AMERICAN SANCTUARY: Mutiny, Martyrdom, and National Identity in the Age of Revolution (Pantheon, $30) tells a similarly dramatic tale — in this case, a good, readable story in the mode of Nathaniel Philbrick’s nautical histories. It has to do with a 1797 mutiny aboard the British warship Hermione that was far more violent than the better known one that occurred on the Bounty eight years earlier. And because some of the mutineers were Americans who had been impressed into British service, and some were turned over to the British Navy by American authorities, it became the Benghazi incident of its time. Federalists tended to see the mutineers as bloodstained murderers, while Jeffersonian Republicans viewed them as men held involuntarily who had a right to seek their liberty. The debate had a significant effect on the election of 1800, turning the vote away from John Adams and toward Thomas Jefferson, the ultimate victor.

The book occasionally falters. The author, A. Roger Ekirch, a historian at Virginia Tech, seems to have a better feel for American political history than for command at sea. For example, a deep sea generally is an advantage for a ship, not a hazard. Similarly, marine officers were more likely to be resented aboard a ship than others, because the marines were effectively naval police, enforcing shipboard discipline. And the second half of the book occasionally bogs down in multiple quotations from newspapers of the time. Still, the level of detail, including verbatim testimony from subsequent courts-martial, is impressive.

A more puzzling work is LINCOLN’S LIEUTENANTS: The High Command of the Army of the Potomac (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $38), by the Civil War stalwart Stephen Sears. It is a fine book, enjoyable to read. All the greatest hits are here — the spectacular feuds between Union generals, the preening of Gen. George McClellan, the pervasive tendency to underestimate President Lincoln’s strategic insight and the tragedy of the battle in the Petersburg Crater.

Continue reading the main story

Yet all this has been well told before. The mystery is why it has to be told once more, especially in a volume of almost 900 pages. This is not an argument that historians should stop writing about the Civil War. But when they do, they should offer new information or a fresh perspective. I found neither here.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Marines conducting a search in Afghanistan in 2009.

Marines conducting a search in Afghanistan in 2009.Credit

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

It is disquieting to turn from these books about the early United States to one about our own century’s war in Afghanistan only to find some of the same flaws from the past, like the attempt to impose capitalist liberal democracy on people long accustomed to very different ways. Aaron B. O’Connell, the editor of OUR LATEST LONGEST WAR: Losing Hearts and Minds in Afghanistan (University of Chicago, $30), calls that country “the worst possible testing ground for a Western democratic experiment conducted at the point of a gun.”

The other contributors to the volume — almost all military veterans of the Afghan war — generally agree that the American people are culturally unable to win wars like this one. “Prudence was blinded by unexamined political and cultural assumptions, and the result was a massive and avoidable waste of time, lives and resources,” Aaron MacLean concludes; he led a Marine infantry platoon there and also holds a master’s degree from Oxford in medieval Arabic studies.

Continue reading the main story

MacLean tellingly observes that the Americans were not trying to bring governance to a place that had none, but rather were trying to replace an existing unwritten constitution they didn’t understand and indeed barely perceived. “It consisted of traditional ethnic, tribal, state and religious patterns, all of which had been partially transformed by modernization and traumatically stressed by decades of war and the rise of Islamic radicalism,” he writes. Surprisingly, no good overview of our Afghan war has been published yet. Until that happens, this enlightening volume is probably the best introduction to what went wrong there, and why.

There is a common thread to almost all wars: They begin with hubris, stumble on miscalculation and end in sorrow. So it was, emphatically, with the Athenian empire’s invasion of distant Sicily in 415 B.C., during the Peloponnesian War. As a result of that poorly considered action, Athens eventually suffered political upheaval. “War abroad had given rise to civil discord at home,” Jennifer T. Roberts writes in THE PLAGUE OF WAR: Athens, Sparta, and the Struggle for Ancient Greece (Oxford University, $34.95). Reading that, I began to wonder if there was a parallel to the unnecessary American invasion of distant Iraq in 2003, and the election of Donald Trump to the presidency some 13 years later. Roberts, a classicist at the City University of New York, notes that as a result of its political turmoil, Athens found its democracy temporarily overthrown by an oligarchical “motley crew with differing goals.”

Do we really need another history of the Peloponnesian War? That was the question in my mind when I opened this book. When I finished it, I thought, yes, we seem to. Military historians often neglect developments in the arts, for instance, but Roberts weaves in Greek culture, showing how works by dramatists and philosophers reflected events in the war. Aristophanes’ “Lysistrata,” about women going on a sex strike to bring peace, was produced in 411 B.C., in the wake of the Athenian disaster in Sicily. She portrays the death of Socrates 12 years later as one more evil consequence of the war, with the great philosopher scapegoated “for the ills of a city that had suffered war, economic collapse, demographic devastation and civil strife.”

Continue reading the main story

A less examined aspect of ancient history is the Praetorian Guard of the Roman emperors. Guy de la Bédoyère, a prolific British historian, tackles the subject in PRAETORIAN: The Rise and Fall of Rome’s Imperial Bodyguard (Yale University, $35). This is not an enjoyable book to read, but it is an interesting one, as the author pulls together the scraps and threads of information about the Guard. The problem is that so little is known about it that the story never really comes alive.

The Harvard historian David Armitage offers another unsettling echo from ancient history when he notes that the Latin phrase variously translated as “public enemy” or “enemy of the people” — the second used by President Trump to describe the American news media — was first devised by Romans in the context of their civil wars, as a way to justify violence against fellow citizens. But overall, his short CIVIL WARS: A History in Ideas (Knopf, $27.95) offers more dry analysis than juicy insights or rich narrative.

Continue reading the main story

Storytelling and details are not lacking in AT THE EDGE OF THE WORLD: The Heroic Century of the French Foreign Legion (Bloomsbury, $30). One of its themes is how routine suicide was in the Legion. Out of 845 Legionnaires sent on an expedition to Madagascar, 11 were officially declared to have taken their own lives. The author, Jean-Vincent Blanchard of Swarthmore College, says that number is almost certainly an undercount, with other self-killings recorded as deaths by disease. Among its interesting details: Near a major Legionnaire base in Morocco, there was a huge government-run prostitution complex, protected by a police checkpoint and populated by 600 to 900 women. Members of the Legion were not allowed to venture more than seven kilometers from their headquarters in Algeria, or to buy drink stronger than wine. The rightist, monarchist, religiously conservative strain in French thought represented by the Legion continues today, of course. Marine Le Pen, the far-right French politician who was recently defeated for the presidency, is the daughter of Jean-Marie Le Pen, who served in the Legion in Vietnam and Algeria in the 1950s.

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Ernie Pyle, center, on a Navy transport to Okinawa, 1945.

Ernie Pyle, center, on a Navy transport to Okinawa, 1945.Credit

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Americans also tend to forget what we as a people once knew. One of the oddities of World War I was that for most of its duration, from August 1914 until April 1917, American reporters were from a neutral country, and so able to cover the fighting from both sides. At the outset, Chris Dubbs reports in AMERICAN JOURNALISTS IN THE GREAT WAR: Rewriting the Rules of Reporting (University of Nebraska, $34.95), the most welcoming country, surprisingly, was Germany, which wanted to present its side of the story to the American public. Britain was less open to having its operations covered, and the French were the strictest censors of all. The Allies arrested reporters while the Germans offered them tours of the front. Among the consequences, Dubbs, himself a journalist turned military historian, notes, was that when the British public finally learned about the horrible nature of trench warfare, it was all the more shocked.

If Dubbs’s book is about how journalists covered World War I, Ray Moseley’s REPORTING WAR: How Foreign Correspondents Risked Capture, Torture and Death to Cover World War II (Yale University, $32.50) is about how the second global war affected the reporters who covered it. Today, too many people have come to think of World War II as the “good war.” One of Moseley’s themes is that there is no such thing. A veteran foreign correspondent, he quotes a British journalist after a German victory in the Sahara: “I found myself hating the desert with a neurotic, tormenting hatred. I was obsessed with the waste of tears and blood and sweat that … I found I could no longer even write about it.”

Continue reading the main story

“Reporting War” makes for melancholy reading. Among the most famous of American war correspondents was Ernie Pyle. Another journalist covering the fighting, The New Yorker’s A. J. Liebling, astutely observed that part of Pyle’s success came from his treating the war not as an adventure or crusade but rather as “an unalleviated misfortune.” After the liberation of Paris, Pyle himself wrote, “For me war has become a flat, black depression without highlights, a revulsion of the mind and an exhaustion of the spirit.”

Pyle died during the landings on Okinawa in April 1945. Such ends were not unusual; Moseley cites one estimate that correspondents suffered a higher casualty rate during the war than combat troops did. After the war, some of those who survived went on to fame, like Walter Cronkite and Eric Sevareid. But many others expired prematurely of alcoholism, depression, midlife heart attacks and car accidents.

Continue reading the main story

One of the lessons of all these books is that wars always look worse closer up. Indeed, one of the tests of the veracity of a history of a conflict is whether it is depressing. If it is not, something may be wrong.

Continue reading the main story

The post New and Noteworthy Books on Military History, from Afghanistan to Waterloo appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Denis Johnson, 'Writer's Writer's Writer,' Dead at 67

This content was originally published by on 26 May 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

The award-winning fiction writer, poet, and playwright, whose best-known and most influential work, the story collection ‘Jesus’ Son,’ turned 25 this year, has died.

Source link

The post Denis Johnson, 'Writer's Writer's Writer,' Dead at 67 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

A Smart, Heartbreaking Novel at the Crossroads of Performance and Art

This content was originally published by JENNY HENDRIX on 26 May 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Photo

Credit

Kari Orvik

THE GIFT

(Or, Techniques of the Body)

By Barbara Browning

Illustrated. 235 pp. Coffee House Press/ Emily Books. Paper, $15.95.

There are times, in our encounters with art, when we find ourselves on the receiving end of an unasked-for gift: the gaze of a girl in a 16th-century portrait; a sustained low note on the cello; the naked muscle of a dancer’s straining limb. In these moments, we may stumble upon what the dancer, writer and performance theorist Barbara Browning, in her blithely metafictional third novel, “The Gift (Or, Techniques of the Body),” refers to as “inappropriate intimacy” — an accidental partnership or exchange, perhaps uncomfortable, yet full of possibilities. Browning, for her part, relishes the creation of such unusual, erotically charged encounters throughout daily life: email spam, performance art, YouTube videos and academic panels each provide opportunities in “The Gift” that she seizes with zest. The result is a smart, funny, heartbreaking and often sexy delight of a novel that presses hard against the boundaries of where literary and artistic performances begin and end. Perhaps no surprise from an artist who likes to “recuperate what might appear to be wasted time by thinking of it as conceptual art.”

Photo

“The Gift” is narrated by one Barbara Andersen, an artist and professor of performance studies in early 2010s New York and an obvious stand-in for Browning herself. She is, among other things, engaged in a continuing art project that involves recording ukulele covers as unsolicited gifts for strangers and friends. In typical artless fashion, she reasons that her uke covers “could possibly help jump-start a creative gift economy that would spill over into the larger world of exchange.” In fact, what the project does do is lead her into a longdistance collaboration with Sami, an autistic music virtuoso in Cologne, Germany. This relationship intensifies, via an online exchange of dances and other gifts, into an intimacy mediated by layers of fiction, vulnerability and lies. Before long, Barbara is forced to wonder whether Sami really is who he claims to be, and the novel tumbles toward an emotional climax no less devastating for turning on an arbitrary linguistic quirk. Meanwhile, Barbara lectures on Pussy Riot, tends her ailing mother, leads workshops through the Occupy movement’s Free University and deepens her friendship with a talented trans performance artist whose work concerns “economic transactions that make art possible or impossible.”

Early on, Browning quotes the cultural critic Lewis Hyde: “In the world of gift … you not only can have your cake and eat it too, you can’t have your cake unless you eat it.” There’s a similar toothsome reciprocity to “The Gift” itself, which takes its title from Hyde’s beloved opus on artistic “giftedness.” While the novel is in one sense part of the recent era of autofictions, several examples of which — “How Should a Person Be?,” “Leaving the Atocha Station,” “I Love Dick” — are mentioned in its pages, there is a sense that “The Gift” is directed outward, toward the reader, rather than toward the writing self. A gift, after all, is a gesture of extension, a concept Browning plays with through Barbara’s “digital” communiqués, whether text, email or erotic “hand dance,” as well as ideas of surrogacy and prostheses — a violin bow, a silicone leg, a rubber phallus. As a novel, “The Gift” incorporates some extended technique as well: Barbara’s dances, stills from which appear in the book, are dances Browning seemingly made in response to and in conjunction with the story she tells.

As author/narrator, Browning/Barbara is delightfully shrewd, if a little daft — an intellectual with scrupulous ethics and a love of organic wool. One tragicomic set piece has her fretting, at length, over something to do with a perfume called “Realism,” not a quality, as it turns out, that concerns her overmuch. The novel’s events bear an uncertain relationship to life, and all of her characters are apparently versions — with varying degrees of authenticity — of actual collaborators, family members, lovers and friends. Some, she writes, gave her input on earlier drafts; some are completely fictional. Such metatextual confessions are, like the rest of the novel, conveyed in a charmingly procedural tone that surprises, at times, with how vulnerable it can be.

“My body is an extension of my body,” Browning writes. The statement has something to do with erogenous zones, something to do with technique, something to do with the way art changes the meaning of things and the ways a person might love. Sometimes, there is no one there to meet the extended hand. Still, as “The Gift” shows, it’s possible for the reaching itself to act as a down payment on a new economy of pleasure.

Continue reading the main story

The post A Smart, Heartbreaking Novel at the Crossroads of Performance and Art appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Books to Breeze Through This Summer

This content was originally published by JANET MASLIN on 25 May 2017 | 9:34 pm.

Source link

SHATTERED: INSIDE HILLARY CLINTON’S DOOMED CAMPAIGN By Jonathan Allen and Amie Parnes. 464 pages. Crown. $28. This is the summer book most likely to be read inside the cover of something else. There’s something guilt-inducing about even wanting to know exactly how the Clinton campaign imploded. Its readers are less likely to be vengeful Hillary-haters than baffled voters wondering how things could go so wrong. “Shattered” promises chapter and verse on that, and it ruefully delivers.

RICH PEOPLE PROBLEMS By Kevin Kwan. 398 pages. Doubleday. $27.95. The Singapore-born Kwan was relatively unknown when he came along with the uproarious satire “Crazy Rich Asians” four years ago. Who would read his outrageous stories of characters who reeled off the brand names of everything they wore or owned, and constantly tried to one-up one another? The answer turned out to be everybody. Kwan followed it up with “China Rich Girlfriend” in 2015, and now “Rich People Problems” ends the trilogy. Even if the problems of the wealthy draw fewer fun-seekers than they used to, Kwan deserves to attract another large audience.

Continue reading the main story

THE FORCE By Don Winslow. 482 pages. William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers. $27.99. (June 20) Winslow, the West Coast star who writes so atmospherically and authoritatively about surfers, drug dealers and horrific drug-related crime, shifts his focus to the South Bronx in his latest book. “The Force” is a stunner of a cop novel, with dialogue, gritty New York setting and moral pincers all in the service of a devastating plot. Clearly invigorated by the success of his previous novel, “The Cartel” (2015), Winslow weaves a complex story around a detective who wants to stay clean even though he’s already dirty.

THE CHICKENSHIT CLUB: WHY THE JUSTICE DEPARTMENT FAILS TO PROSECUTE EXECUTIVES By Jesse Eisinger. 400 pages. Simon & Schuster. $28. (July 11) The title of this nonfiction account of the government’s failure to prosecute white-collar criminals was inspired by the former F.B.I. director and current newsmaker James Comey. He was the United States attorney for the Southern District of New York and a former federal prosecutor when he gave a speech to prosecutors working under him, asking how many of them had ever had an acquittal or a hung jury. If they hadn’t, Comey said, they were members of the above-mentioned club: too chicken-hearted to take on the really tough stuff. This book provides a history of how, in the opinion of its Pulitzer Prize-winning author, the Justice Department has gotten soft.

Photo

Credit

Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

THE DINNER PARTY: AND OTHER STORIES By Joshua Ferris. 246 pages. Little, Brown. $26. Everything comes mordantly alive in the priceless imagination of Ferris, who can describe an onion being diced and think of the other vegetables near it as “bright and doomed.” Here’s a welcome chance to read stories that have appeared in publications from The New Yorker to Prairie Schooner, and his perverse short narratives do not disappoint. If you’re looking for happy endings, go somewhere else. Ferris’s view of the human condition falls somewhere between Woody Allen’s and Franz Kafka’s. A Ferris story can merrily pave the way from bad to worse.

Continue reading the main story

WE ARE NEVER MEETING IN REAL LIFE: ESSAYS By Samantha Irby. 275 pages. Vintage. $15.95. The second book of essays from this frank and madly funny blogger includes pieces titled “You Don’t Have to Be Grateful for Sex,” “I’m in Love and It’s Boring,” “A Case for Remaining Indoors” and “The Real Housewives of Kalamazoo.” Her opening essay alone is enough to make this collection a winner. It starts with a fake application to become a “Bachelorette” contestant, and then details how the show would be different if she were on it, including the wardrobes. (“I don’t wear evening gowns and booty shorts every day. I wear daytime pajamas and orthopedic shoes, and lately I have become a big fan of the ‘grandpa cardigan.’”) A sidesplitting polemicist for the most awful situations.

Continue reading the main story

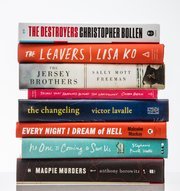

MAGPIE MURDERS By Anthony Horowitz. 496 pages. Harper/HarperCollins Publishers. $27.99. (June 6) Take a perfect faux version of an Agatha Christie Hercule Poirot book. Call the detective in it Atticus Pünd. Make Pünd’s creator a writer named Alan Conway. Write a full mid-20th-century book starring Pünd called “Magpie Murders.” Then wrap this fake novel in a “real” present-day one in which Conway dies, and you have the mystery lovers’ buffet that is Horowitz’s latest novel. “Magpie Murders” is a double puzzle for puzzle fans, who don’t often get the classicism they want from contemporary thrillers.

NO ONE IS COMING TO SAVE US By Stephanie Powell Watts. 371 pages. Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers. $26.99. Set in North Carolina, Watts’s book envisions a backwoods African-American version of “The Great Gatsby.” The circumstances of her characters are vastly unlike Fitzgerald’s, and those differences are what make this novel so moving. No frivolity or superficiality here. JJ Ferguson, the dreamer who returns home to woo his now-married sweetheart by building a big house, is positively pragmatic by Gatsby standards.

THINGS THAT HAPPENED BEFORE THE EARTHQUAKE By Chiara Barzini. 320 pages. Doubleday. $26.95. (Aug. 15) An Italian teenage girl shows up in 1990s Southern California in this culturally astute, strong-voiced novel. Barzini, truly a writer to watch, positions herself astride both American and Sicilian cultures, and packs this visceral book with strong sensations from both. The novel and its heroine, Eugenia, are deeply seductive.

EVERY NIGHT I DREAM OF HELL By Malcolm Mackay. 291 pages. Mulholland Books/Little, Brown. $26. Mackay’s hard-boiled books set in Scotland aren’t well known in the United States, but there’s a reason those who know them love them. His Glasgow Trilogy is classic, and this new book brings forth Nate Colgan, an earlier Mackay character, to narrate. The subject is organized crime, but it’s the author’s blunt eloquence that matters. Don’t pick up a Mackay book unless you’ve got spare time. They’re habit-forming.

Photo

Credit

Tony Cenicola/The New York Times

THE CHANGELING By Victor LaValle. 431 pages. Spiegel & Grau. $28. (June 13) This novel is afflicted with an unfortunate Anthony Doerr blurb calling LaValle a mix of Haruki Murakami and Ralph Ellison. That just proves how fiercely it defies categorization. Written as a self-proclaimed “fairy tale” in a punchy, inviting style, Mr. LaValle’s haunting tale weaves a mesmerizing web around fatherhood, racism, horrific anxieties and even “To Kill a Mockingbird.” And the backdrop for this rich phantasmagoria? The boroughs of New York.

Continue reading the main story

THE JERSEY BROTHERS: A MISSING NAVAL OFFICER IN THE PACIFIC AND HIS FAMILY’S QUEST TO BRING HIM HOME By Sally Mott Freeman. 588 pages. Simon & Schuster. $28. The subtitle of Mott’s first foray into highly dramatic history says it all. Her book is liable to break the hearts of “Unbroken” fans, and it’s all true. Happy Father’s Day. You’re welcome.

THE DESTROYERS By Christopher Bollen. 480 pages. Harper/HarperCollins Publishers. $27.99. (June 27) Beautiful people visiting glamorous places, being wicked enough to bring Patricia Highsmith to mind. It just isn’t summer without this kind of globe-trotting glamour to read about, especially when most of it is set in the Aegean. Bollen is stylish enough to know what sells, and happy to write sentences like: “Marisela single-handedly rendered my cherished porn sites irrelevant.” Escapism, as calculating as it gets.

THE LEAVERS By Lisa Ko. 338 pages. Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. $25.95. This wrenching and all-too-topical debut novel picks up the life of an 11-year-old American-born boy on the day his mother, an undocumented Chinese immigrant, disappears. As with the recent film “Lion,” he has adoptive white parents in his life and a missing mother on his mind. Ko uses the voices of both the boy and his birth mother to tell a story that unfolds in graceful, realistic fashion and defies expectations. Though it won last year’s PEN/Bellwether Award for Socially Engaged Fiction, Ko’s book is more far-reaching than that.

Continue reading the main story

And lastly, notes on a couple of additional titles: John A. Farrell’s biography “Richard Nixon: The Life” is a great read that will come up in conversation frequently and possibly win prizes. And for Lee Child fans, his previously published Jack Reacher stories and a new novella have been collected in “No Middle Name.” Its cover depicts a cup of coffee, and if you’ve read about Reacher you know why. If not, get started.

Continue reading the main story

The post Books to Breeze Through This Summer appeared first on Art of Conversation.

PW Picks: Books of the Week, May 29, 2017

This content was originally published by on 26 May 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

This week: David Sedaris’s diaries, plus the complete Jack Reacher stories.

Source link

The post PW Picks: Books of the Week, May 29, 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

12 New Books We Recommend This Week

This content was originally published by on 25 May 2017 | 9:47 pm.

Source link

HE CALLS ME BY LIGHTNING: The Life of Caliph Washington and the Forgotten Saga of Jim Crow, Southern Justice, and the Death Penalty, by S. Jonathan Bass. (Liveright, $26.95.) A young black man wrongly accused of killing a policeman in Alabama in 1957 faced a 44-year legal battle, during which Gov. George Wallace stayed his execution no less than 13 times. This painstakingly documented story offers a counterpoint to the master narrative of progress that characterizes our popular memory of the civil rights movement, and connects the movement’s gains and limitations to the current crisis of race and criminal justice.

Continue reading the main story

RISING STAR: The Making of Barack Obama, by David J. Garrow. (Morrow/HarperCollins, $45.) This long, deeply reported but gratuitously snarly biography argues that the young president-to-be subordinated everything, including love, to a politically expedient journey-to-blackness narrative. The depth of detail allows the reader to see familiar parts of Obama’s story with fresh eyes.

THE GOLDEN LEGEND, by Nadeem Aslam. (Knopf, $27.95.) In Aslam’s powerful and engrossing fifth novel, set in an imaginary Pakistani city ruled by mob violence, sectarianism and intolerance, the principal characters become hunted fugitives. Their integrity and courage nevertheless provide hope, and Aslam writes with great sensitivity and depth about the ways human beings behave under almost unimaginable pressure.

THE UNRULY CITY: Paris, London and New York in the Age of Revolution, by Mike Rapport. (Basic Books, $32.) What accounts for differing degrees of upheaval when societies are in crisis? A historian’s examination of the 18th-century revolutions in urban Britain, America and France reminds us that the democratic structures that have supported us for so long came about as a result of convulsions of the established order.

MEN WITHOUT WOMEN: Stories, by Haruki Murakami. Translated by Philip Gabriel and Ted Goossen. (Knopf, $25.95.) In this slim (seven stories) but beguilingly irresistible book, Murakami whips up a melancholy soufflé about wounded men who can’t hold on to the women they love. All signature Murakami elements are present and accounted for: a rainy Tokyo, neat single malt, stray cats, cool cars and classic jazz.

Continue reading the main story

SCARS OF INDEPENDENCE: America’s Violent Birth, by Holger Hoock. (Crown, $30.) This important and revelatory book adopts violence as its central analytical and narrative focus, forcing readers to confront the visceral realities of a conflict too often bathed in warm, nostalgic light. The Revolution in this telling is a war like any other, characterized not by dexterous verbal battles but by rape, plunder and blood-soaked battlefields.

Continue reading the main story

CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’: Cass Elliot Before the Mamas and the Papas, by Pénélope Bagieu. (First Second, $24.99.) Bagieu uses the entire range of her medium, graphite, to show — in drawings both exuberant and sad — how a Baltimore girl named Ellen Cohen grew up to became Mama Cass of the Mamas and the Papas, the ’60s band of “California Dreamin’” fame. Exuberance and sadness coexist in Bagieu’s drawing style, as they coexist in the character of Cass Elliot.

FIRST LOVE, by Gwendoline Riley. (Melville House, paper, $16.99.) A 30-something writer falls in love with and marries a man who says he doesn’t “have a nice bone in my body.” This dark, funny novel displays its author’s mastery of scrupulous psychological detail and ear for the ways love inverts itself into cruelty.

Continue reading the main story

THE LONG DROP, by Denise Mina. (Little, Brown, $26.) In a departure from her usual series featuring sleuths Alex Morrow and Paddy Meehan, Mina’s new novel is based on a real crime spree that horrified Glasgow in the late 1950s, when the wife, sister-in-law and daughter of a bakery-shop owner were murdered.

Continue reading the main story

The post 12 New Books We Recommend This Week appeared first on Art of Conversation.