Roy Miller's Blog, page 173

June 1, 2017

Thoreau: American Resister (and Kitten Rescuer)

This content was originally published by HOLLAND COTTER on 1 June 2017 | 9:14 pm.

Source link

At the center of the installation is the slant-top Walden desk, on first-time loan from the Concord Museum in Massachusetts. In a sense, the whole show fans out from it. Thoreau bought the desk soon after graduating from Harvard, when he and his older brother, John, opened a school near their home in Concord. When the school abruptly closed — John died of tetanus at 26 after nicking himself with a razor — Thoreau kept the desk.

Photo

Thoreau’s desk, made of Eastern white pine and painted green, from around 1838.

Credit

Concord Museum

He probably used it as a drafting table when he took up work as a land surveyor. (His protractor and compass are on display.) It almost certainly served as a reading station for Thoreau the perpetual student, poring over Hindu scriptures, ornithological guides and philosophical tracts by his neighbor, mentor and frenemy, Ralph Waldo Emerson. And it was essential equipment for the full-time writer he became, privately as the lifelong keeper of a daily journal, and publicly as a lecturer and essayist.

Photo

Thoreau’s goose quill pen, with a note from his sister Sophia: “The pen brother Henry last wrote with.”

Thoreau’s goose quill pen, with a note from his sister Sophia: “The pen brother Henry last wrote with.”Credit

Concord Museum

The show, organized by Christine Nelson of the Morgan and David Wood of the Concord Museum, is divided into sections corresponding to facets of Thoreau’s identity — student, worker, reader, writer — using the journal as the binding thread, which the Morgan is ideally positioned to do: Almost all the surviving journals, about 40 handwritten volumes, are in its permanent collection.

Continue reading the main story

They constitute one of New York’s great manuscript treasures and are the most direct and absorbing way to approach Thoreau himself. Several open volumes appear in the show, with passages keyed to events in the writer’s life. Through their words, a drama builds and a personality emerges, one surprisingly different from the antisocial and self-denying Thoreau of modern legend.

Continue reading the main story

The writer is, for one thing, a sensualist, responding to physical stimuli — light, scent, taste — “as if I touched the wires of a battery.” He’s superalert to sound: wind, ice cracking, energy humming in telegraph lines. He knows the music of birds, the “sonorous quavering” of geese overhead, the song of the wood thrush and vesper sparrow. And he makes music of his own, on a flute that had belonged to his brother (it’s in the show), which he delighted in playing outdoors.

Photo

A page from Thoreau’s journal notebook from Nov. 11, 1858.

A page from Thoreau’s journal notebook from Nov. 11, 1858.Credit

Morgan Library & Museum

Far from being a recluse, Thoreau spent much of his time with people, often seeking them out. He had problems with some: with cocksure authorities; with self-promoters (a brief stint in Manhattan trying to break into publishing was a disaster); and with uptight members of the Concord bourgeoisie. He froze when it came to small talk (Hawthorne had the same disability), and prolonged socializing with company not of his choosing left him drained. But he was a devoted family member; a reliable friend (the prickly Emerson leaned on him in times of personal crisis); and a favorite of children, with whom he spent much time.

Continue reading the main story

If his regard for the human race deteriorated as he grew older, there were reasons. He watched with alarm and disgust as industrial wealth created a new socio-economic elite, and America’s imperialist appetites strengthened. As his love of the natural world turned acute — he came to believe trees had souls — he moved toward a zero-tolerance stance on human predation: on the wanton hunting of animals, on laying waste to the land.

“Is our life innocent enough?” he asked. No. “Do we live inhumanely — toward man or beast — in thought or act?” Regrettably, yes.

His sympathies were with the outcast, the downtrodden: the Irish laborers shunted to the outskirts of Concord, the dispossessed Native Americans he met on his travels. His journal is marred by ethnic stereotypes, amounting to slurs, common to his time, but his expression of empathy feels gut-level genuine. In the case of Native Americans, it produced thousands of pages of anthropological research.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, securing the return of runaways, tipped him over the edge from outrage to activism, though his upbringing had primed him to make the move. His mother was a founder of the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society; his older sister, Helen, was a friend of Frederick Douglass; the family home, where, aside from two years at Walden, he lived till he died, was a stop on the Underground Railroad to Canada. Given this context, his night in jail, in 1846, for refusing to pay taxes to a slavery-supporting government was a less sensational event than history has tried to make it. (It’s nice, nonetheless, to see the lock and key from his jail cell in the show.)

Photo

Steel lock and key from the cell where Thoreau spent a night in jail for tax resistance in 1846.

Steel lock and key from the cell where Thoreau spent a night in jail for tax resistance in 1846.Credit

Concord Museum

Riskier actions came later, when in 1854 he delivered a furious antislavery speech while standing under a black-draped, upside-down American flag on a stage shared with Sojourner Truth. And he hit still harder in near-treasonous defense of the radical abolitionist John Brown in 1859. In both cases, he carefully culled ideas and words from the journal, the one place he let himself talk freely, experimentally and completely.

Continue reading the main story

It took time to learn to do this, and you can see the process in action. In the earliest journal, dated 1837, the penmanship is crisp, the margins precise. By the time we come to the final volume, left half-empty at Thoreau’s death in 1862, the writing scrawls at a tilt to the very edges of the page — top, bottom and sides — as if the writer were afraid he would not have the time and space to fully express the “ever new self” that the journal-writing had given him access to.

Continue reading the main story

After my early love, there was a long stretch when I put Thoreau down — literally. Didn’t read him. I became a city person. I was in a rush, or a mood, or a mess, and the Transcendentalists read too slow, sounded too preachy, felt too above it all. Recently, though, with a new Thoreau biography on the horizon (by Laura Dassow Walls, due out in July) and the Morgan show scheduled, I went back to him.

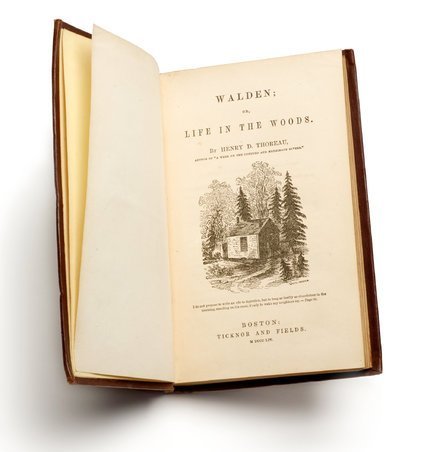

Photo

The first edition of “Walden; or, Life in the Woods,” from 1854.

The first edition of “Walden; or, Life in the Woods,” from 1854.Credit

Morgan Library & Museum

I ferreted out my slender old Walden copy of the journal and found Thoreau’s “ever new self” where I’d left him, and now, once again, so relatable! Here he is speaking out on “the baseness of politicians” and the plight of immigrants, insisting that black lives more than just matter, and that America will never rest until it begins — begins — to try to repair the damage it has done to its indigenous people.

Continue reading the main story

There’s more. Why hadn’t I remembered, during the terrible years of the AIDS crisis, the tenderness of Thoreau’s nursing and the devastation he felt when people he loved, like John, sickened and died? And how could I have missed understanding that Thoreau’s love of nature was not Emersonian; it was, minus sainthood, Franciscan. “Of thee, O earth, are my bone and sinew made. To thee, O sun, am I a brother.”

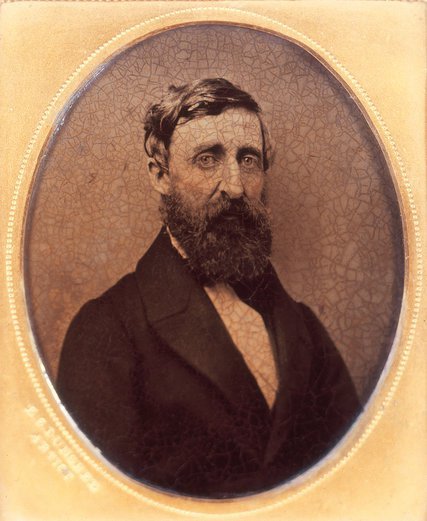

Photo

Henry David Thoreau in an ambrotype portrait from 1861 by Edward Sidney Dunshee.

Henry David Thoreau in an ambrotype portrait from 1861 by Edward Sidney Dunshee.Credit

Concord Museum

I found evidence, again, that Thoreau could be cranky, misanthropic, a pain. This is old news. People forgave him, or didn’t. But how could I have missed his sweetness?

“When yesterday Sophia and I were rowing past Mr. Prichard’s land, where the river is bordered by a long row of elms and low willows, at 6 p.m., we heard a singular note of distress.” Thoreau, thinking a bird was in trouble, rowed to shore to help, then saw “a little black animal making haste to meet the boat. A young muskrat? A mink? No, it was a little dot of a kitten. Leaving its mewing, it came scrambling over the stones as fast as its weak legs would permit, straight to me. I took it up and dropped it into the boat, but while I was pushing off it ran the length of the boat to Sophia, who held it while we rowed homeward.”

Continue reading the main story

This journal entry dates from May 1853, which would put it well along in the chronological arc that surrounds the green-painted desk in the show. By that point, you’ve already been through the better part of an instructive and generous life. And just by paying attention to it, you have indeed, like leaving a stone at Walden, added something to history: your own.

Correction: June 1, 2017

An earlier version of this article misstated the surname of a curator of the exhibition. He is David Wood, not Cook.

Continue reading the main story

The post Thoreau: American Resister (and Kitten Rescuer) appeared first on Art of Conversation.

BookExpo 2017: Paying Tribute to Rock and Roll—and Ghana: Kwame Alexander

This content was originally published by on 1 June 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

“Despite our differences and our individual struggles and successes in life, music is the universal language,” says Kwame Alexander. “It can be the thread that connects us all.” Music is the catalyst for Alexander’s new YA novel-in-verse, Solo (Harper/Blink, Aug.), cowritten with his close friend, collaborator, and poet, Mary Rand Hess. “It’s a love letter to rock and roll music,” he explains. “It’s a tribute, an ode to my teenage years and how music was the thing that sort of helped me stay sane and really got me on a journey to understanding myself a little better.”

Blade, the teenage protagonist of Solo, is on a path to self-acceptance, too. He’s a talented musician in his own right, but is living in the shadow of his famous rock star dad, who is battling addiction. The other curve balls in Blade’s life include the loss of his mother several years earlier, a recent romantic heartbreak, and a newly revealed family secret. “He’s in an uphill battle trying to find himself,” says Alexander, “and the journey he’s on takes him from Hollywood across the world to Ghana, to a whole other culture where he’s able to begin to understand his place in the world.”

Alexander says he wanted to include Ghana in Solo because the country is near to his heart. He has been traveling there for the past five years to work on a literacy initiative he cofounded to help students and teachers, and to build a library in the village of Konko, in the eastern region of the country. “I have spent so much time there, I wanted to write about that experience,” he adds.

Alexander shares his passion for Blade’s story with Hess. The pair had previously teamed up for a picture book (Animal Ark, National Geographic) and are in the same writing group. “We are both hopeful romantics who are in love with love, and we consider ourselves to be huge poetry enthusiasts,” says Alexander.

Alexander and Hess recently finished a first draft of their second YA novel, Swing, which will also be published by Blink. “We pay homage to jazz and baseball—two of the greatest things ever created by Americans,” says Alexander. “Swing is a hybrid of verse, poems, epistolary, and some prose—and it moves between a contemporary setting and the 1930s.” Alexander has also completed Rebound, a prequel novel-in-verse to his Newbery-winning The Crossover (HMH, April 2018.

Alexander and his writing group colleagues are headed to Ghana for a summer retreat. “It’s interesting that during the last week of July, we’ll be in Ghana cutting the ribbon on the new library and brainstorming ideas for our future projects, and when we return from doing all that, Solo will be published,” Alexander says. “It’s a wonderful time for the book and for us.” And the author is in the process of building a writing studio, which, he explains, “I’ve built to the specifications that will allow all of us to be able to be in there, have our space, and enjoy our writing group in the truest sense of the word.”

Today, 11 a.m.–noon. Kwame Alexander and Mary Rand Hess will sign ARCs of Solo in the Autographing Area, at Table 3.

The post BookExpo 2017: Paying Tribute to Rock and Roll—and Ghana: Kwame Alexander appeared first on Art of Conversation.

9 New Books We Recommend This Week

This content was originally published by on 1 June 2017 | 10:07 pm.

Source link

THE ALLURE OF BATTLE: A History of How Wars Have Been Won and Lost, by Cathal J. Nolan. (Oxford University, $34.95.) The traditional Western view of conflict is that the way to win a war is to seek battle and prevail. This thought-provoking book suggests a new approach to military history: Nolan argues that focusing on battles is the wrong way to understand wars, because attrition is what almost always wins.

Continue reading the main story

ERNEST HEMINGWAY: A Biography, by Mary V. Dearborn. (Knopf, $35.) Hemingway’s outsize life and controversial achievement are a magnet to biographers, and Dearborn is the first woman to join their company. A feminist biography, then? Not exactly. Her chief asset, she says, is her immunity to the hairy-chested Hemingway legend; instead, she focuses on “what formed this remarkably complex man and brilliant writer,” skillfully covering an enormous range of rich material.

MUSIC OF THE GHOSTS, by Vaddey Ratner. (Touchstone, $26.) This tenaciously melodic novel explores art and war as an orphaned Cambodian refugee travels from her new home in Minneapolis to the Buddhist temple where her father was raised by monks, hoping against hope that he is still alive. The author discerns the poetic even in brutal landscapes and histories, forging musical phrases from conflict.

WHERE THE LINE IS DRAWN: A Tale of Crossings, Friendships and Fifty Years of Occupation in Israel-Palestine, by Raja Shehadeh. (New Press, $25.95.) In deeply honest and intense essays, Shehadeh, a civil rights lawyer and the author of “Palestinian Walks,” who now lives in Ramallah, describes his psychological and physical crossings into Israel. Through his friendship with a quirky Jungian analyst named Henry Abramovitch, a Canadian immigrant to Israel, Shehadeh reflects the 50-year history of the occupation and the elusive quest for peace.

THE WITCHFINDER’S SISTER, by Beth Underdown. (Ballantine, $28.) An English witch hunter, Matthew Hopkins, caused more than a hundred women to be hanged in the 1640s. Hopkins and his reign of terror exist in the historical record, but little is known about his private life. In this ominous, claustrophobic novel, Underdown imagines his pregnant, widowed sister, who sees the malignant forces at work but is powerless to resist.

FEN: Stories, by Daisy Johnson. (Graywolf, paper, $16.) The stories in Johnson’s debut collection explore the shape-shifting world of the Fens, once flooded lands in the east of England. Here, where both land and life are flat, the privations of rural teenage existence yield wild and elemental bewitchments.

Continue reading the main story

The post 9 New Books We Recommend This Week appeared first on Art of Conversation.

BookExpo 2017: Big New Kids' Books

This content was originally published by on 1 June 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Children’s book publishers were highlighting titles for all ages and interests as BookExpo got underway on Thursday.

Source link

The post BookExpo 2017: Big New Kids' Books appeared first on Art of Conversation.

‘On Fire’ Makes Bad Habits Sound Very Sweet

This content was originally published by DWIGHT GARNER on 1 June 2017 | 10:13 pm.

Source link

At least twice a year someone will ask me if I can recommend a book to give a man who doesn’t read as much as he might. I nearly always reply: “On Fire,” by Larry Brown. It’s a gateway drug. It’s literary writing of a sort that says, Come as you are.

Photo

Credit

Sonny Figueroa/The New York Times

I am opposed to trigger warnings, but “On Fire” should probably have them. This book will make you want to start smoking again. (Until you recall that Brown died, apparently of a heart attack, at 53.) It may make you want to drink beer while driving slowly and looking at the world, in the late-evening light, while listening to music in the front seat of a pickup truck — one of Brown’s favorite activities. I cannot in good conscience recommend these things. But Brown does make them sound very sweet indeed.

A few chapters in “On Fire” are about things like dogs, hunting and family. Brown describes his battles, at his rural house, with spiders, mice, coyotes and ticks. These descriptions mostly cannot be printed in this newspaper.

Continue reading the main story

About ticks, he writes: “We were afraid we were going to have to burn the house down just to get rid of them. It made us feel like inferior people, although we knew it wasn’t our fault. When company was over we’d be shifting our eyes around, looking to see if one was walking.”

Continue reading the main story

Most of this book is about Brown and his fellow Oxford firefighters rolling toward unnerving fires and terrible car accidents. On his way, his mind plays over lessons and scenarios:

“Remove the car from the victim, not the other way around. You can be faced with anything. A car upside down on top of two people, one dead, one alive. A head-on collision, two dead, two alive, one each in each car. A car flipped up on its side against a tree, the driver between the roof and the tree. A burning car with live occupants trapped inside.”

Brown writes vividly about his fears — about someone dying because of his error, about letting his co-workers down. But he’s just as good on the sort of pride that comes with mastery.

Continue reading the main story

“I love the way the lights are set up on the side of the road at a wreck and I love the way the Hurst Tool opens with its incredible strength and I love the way it crushes the roof posts of a car and I love the way you can nudge it into the hinges of a door and pop the pins off and let the door fall and reach in to see your patient’s legs and what position they are in.”

Continue reading the main story

He continues: “I love to drive to any incident, love to run the siren, to run fast but careful through town. I love the smell of smoke and the feeling of fear that comes on me when I see that a fire is already through the roof and licking at the sky because I know that I am about to be tested again, my muscles, my brain, my heart.”

He’s just as good — forgive me for quoting to this extent — on a firefighter’s downtime, “the movies we watch at the station and the meals we cook and eat and the targets we shoot with our bows in the afternoons, washing our cars and trucks in the parking lot and sitting out front of the station in chairs at night hollering at people we know passing on the street.”

Early in his career, Brown chafed against being labeled “the fireman-writer.” It sounded cute. Now that he’s long since escaped that fate, his firefighting book needs to be better known.

If you are among the tens of millions who have never read Brown, this is a perfect introduction. He felt life deeply, had a vast understanding of his world and paid attention to what mattered. His basic decency shines through these pages.

Among Southern writers, Brown was one of those who didn’t have too much syrup in him. His prose in “On Fire” is fresh, light on its feet, ready for anything. If this book were a restaurant, I’d eat there all the time.

Continue reading the main story

The post ‘On Fire’ Makes Bad Habits Sound Very Sweet appeared first on Art of Conversation.

BookExpo 2017: Beyond ‘Mad Men’: Matthew Weiner

This content was originally published by on 1 June 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

By Hilary S. Kayle

|

After seven seasons (92 episodes) of Mad Men, friends advised writer Matthew Weiner, the series creator, to take a break. “They said, ‘You know you should just stop and refill your tank and take things in.’ That turned out to be really scary because as a writer, you’re always worried if you’re ever going to write again. At the same time, it was transformative,” Weiner says.

At a friend’s suggestion Weiner, who also worked on The Sopranos, went to Yaddo, the artists’ retreat in upstate New York, to figure out what he wanted to work on next. “I had a play that I could rewrite [and] a movie idea, and then I started working on what I thought was a short story. It was inspired by something I had seen a few weeks beforehand and had written down,” Weiner says. “I walked past this beautiful schoolgirl going into a building under construction, and I saw a man working there stare at her with threatening intensity. I don’t have any daughters, but what I wrote down was, ‘What if her father saw that?’ I thought I’ll just see if I can write a little bit on this, and then it took off. I came back from Yaddo, and I was on fire with it. It was a chance to tell a story in a way that I had never told it before.”

The result is Weiner’s debut novel, Heather, the Totality (Little, Brown, Oct.), and his enthusiasm about it is palpable. “This is my childhood dream come true,” he says. “I don’t want to diminish my experience in film and TV, but writing fiction—prose really—is what I perceived as writing when I was a kid. And writing this novel and actually finishing it, I was in a very different expressive environment than my previous work.”

While Weiner’s work on The Sopranos as well as on Mad Men was a collaborative effort, writing a novel is very different. “When I write for the screen,” he explains, “I work off an outline done in a group. After I finish a script, it goes back into the writers’ room. The writers give notes without me there, and they can be brutal. Then the writers’ assistant brings back the script for a rewrite. It always makes things better. But with this novel, everything was done alone, including sitting down at the computer for the first time in years. The writing became linguistically more intimate and internal.

“There’s also no budgetary constraint on where you go in the story: location, casting, sets,” Weiner adds. “Another difference: you may not have distribution when you’re done with a novel, but the thing you’re working on is the final product. A script is a blueprint for a product, and a great script will frequently result in a good product—but it’s not the end result.”

A first-time attendee at BookExpo, Weiner is delighted to be here. “This is all new to me,” he says. “And because I’ve been a professional writer with some kind of success, everyone’s kind of laughing at how excited I am about this. This is my first book, my first time in this world. I’m very excited for people to see it and read it.”

Today, 3–4 p.m. Matthew Weiner will sign at the Hachette booth (2502).

The post BookExpo 2017: Beyond ‘Mad Men’: Matthew Weiner appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Paris Poisoners and a Pioneering Female Detective: Your True Crime Books for the Beach

This content was originally published by MARILYN STASIO on 1 June 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

If the 17th century was enamored of highborn villains, the Victorian age admired master sleuths with uncanny deductive skills, like Émile Gaboriau’s wily French police detective, Monsieur Lecoq, and, of course, Arthur Conan Doyle’s immortal Sherlock Holmes. In his lively literary biography ARTHUR AND SHERLOCK: Conan Doyle and the Creation of Holmes (Bloomsbury, $27), Michael Sims traces the real-life inspiration for the first “scientific detective” to the renowned Dr. Joseph Bell, a lecturer at the University of Edinburgh celebrated for his uncanny diagnostic observational skills. His methods were “quite easy, gentlemen,” Dr. Bell would assure his students. “If you will only observe and put two and two together,” you, too, could deduce a man’s profession, family history and social status from the way he buttons his waistcoat.

Continue reading the main story

Consulting detectives like Holmes are the heroic role models of a long-ago age. Modern detectives work out of police departments, where they sometimes find themselves investigating their fellow officers. BLUE ON BLUE: An Insider’s Story of Good Cops Catching Bad Cops (Scribner, $28) is an exposé of the secretive work of the N.Y.P.D.’s Internal Affairs Bureau, written (with Gordon Dillow) by Charles Campisi, chief of that agency for almost 18 years. In police procedurals, bent cops live in fear of being called before the I.A.B., an awesomely powerful arm of the department charged with dealing with the dirt kicked up by crooked cops and questionable police practices. At first, Campisi writes with the voice of a Noo Yawker trying to be polite to visitors from another planet. But when he loosens up he’s enlightening — and entertaining — on the procedures of this shadowy agency, feared by many, admired by those who work for the I.A.B.

Enough about the cops. Let’s get to the killers. In THE AXEMAN OF NEW ORLEANS: The True Story (Chicago Review, $26.99) Miriam C. Davis resurrects a madman with a meat cleaver (the ax came later) who made his first attack on a summer night in 1910. His victim was an Italian grocer who survived the assault. Over the next 10 years, he attacked and robbed a string of grocers, mainly Italian, and their wives. Some of them did not survive. In the middle of his rampage, the Axeman sent a letter to The New Orleans Times-Picayune, declaring himself “a fell demon from the hottest hell” and promising to spare anyone listening to jazz on the designated night of his next attack. This being New Orleans, the city was ablaze with lights and jazz music all through the night.

Davis speculates that the Axeman, determined by the police to be a career criminal named Joseph Mumfre who was shot and killed by one of his intended victims, actually slipped through the police dragnet and lived to kill again. It’s a shaky claim, but well argued. And who knows? As Davis reflects: “Perhaps in some obscure small-town newspaper there’s a story of an intruder caught fleeing an Italian grocery in the middle of the night after attacking the proprietor and his wife.”

Continue reading the main story

Killers are rarely as colorful as the Axeman; they’re more likely to be nondescript creeps like Lonnie Franklin Jr., the villain of THE GRIM SLEEPER: The Lost Women of South Central (Counterpoint, $26). This upsetting account of a Los Angeles serial killer, written with passion by Christine Pelisek, an investigative crime reporter who spent 10 years working the case, blurts out a hard truth that no one wants to acknowledge: “Body-dump cases” aren’t sexy. L.A. loves its gaudy killers and gives them fun names like the Dating Game Killer and the Skid Row Slasher. But nobody bothers to baptize nonentities like Franklin, who killed an estimated 38 black, crack-addicted prostitutes since 2002 (many more, if you go back to the ’90s and count the ones in Fresno) and dumped their remains all over the county.

Continue reading the main story

As “the most invisible and vulnerable class of people,” dead prostitutes are small potatoes when you consider that in 2006 there were six serial killers preying on the same 51-square-mile area of South Central L.A. Pelisek works up a froth of outrage about this and tries to restore dignity to some of the victims by drawing sympathetic and carefully detailed life histories for each and every one of them. The sad thing is, the recurring pattern of their lives — the unhappy home, the runaway escape, the demanding pimp, the drug addiction — destroys their individuality and makes each victim indistinguishable from all the others.

Although women make ideal victims, not all women are born equal in the eyes of true crime writers. Emilie Le Beau Lucchesi touches on that raw nerve in the criminal justice system in UGLY PREY: An Innocent Woman and the Death Sentence That Scandalized Jazz Age Chicago (Chicago Review, $26.99). By revisiting the forgotten 1923 case of Sabella Nitti, the first woman sentenced to be hanged in Chicago, she exposes the real reason behind that harshest of legal judgments. Unlike those blond babes (like Roxie Hart, the floozy in the musical “Chicago”) who were cleared of homicide by all-male jury trials, Sabella, an Italian immigrant who was as plain as a mud fence, was destined for the gallows.

Continue reading the main story

“It was the defendant’s looks, most women agreed, that brought in the guilty verdict. The juries in Chicago were biased, and a beautiful woman … got away with murder, but women like Sabella got the noose,” Lucchesi notes. Poor, illiterate and unable to understand English, Sabella was accused, without proof, of murdering her abusive husband. But in the unkind words of one female reporter, she was a “dumb, crouching, animal-like peasant” with dark, leathery skin and greasy hair. In Sabella’s own cynical judgment, “Pretty woman always not guilty.”

Grace Humiston was an advocate for an earlier generation of lost and forgotten women, and her inspiring story demands a hearing. In MRS. SHERLOCK HOLMES: The True Story of New York City’s Greatest Female Detective and the 1917 Missing Girl Case That Captivated a Nation (St. Martin’s, $27.99), Brad Ricca makes a heroic case for Humiston, a lawyer and United States district attorney who forged a career of defending powerless women and immigrants. She took on causes like the exploitation of illiterate Italian laborers and the sexual enslavement of young girls. For her dogged work on the 1917 case of a missing girl that the police had given up on, the newspapers called her “Mrs. Sherlock Holmes.” With the snow coming down on a bitter cold day in February, 18-year-old Ruth Cruger left her family’s home in Harlem to take her ice skates to a repair shop and promptly disappeared. Pretty young girls who go missing put the police on high alert and make the New York tabloid press go nuts. A month later, the police found a witness who saw Ruth get into a taxicab with a young man. After that, the trail went cold. But Humiston persevered, tracing her to a cellar where a local gang kept girls bound for the South American white slave trade. Yes! You can read it here: There really was a South American white slave trade, and crusaders like Grace Humiston really did rescue young girls from “a fate worse than death.”

Authors of true crime books have made a cottage industry out of analyzing what makes killers tick. Michael Cannell gives credit where credit is due in INCENDIARY: The Psychiatrist, the Mad Bomber, and the Invention of Criminal Profiling (Minotaur, $26.99) by profiling one of the pioneers, Dr. James A. Brussel, a New York psychiatrist who specialized in the criminal mind. In 1920, a horse-drawn wagon carrying 100 pounds of dynamite pulled up on Wall Street and exploded, killing 38 people and igniting a raging fire that swept down the street and sent hundreds of pedestrians running for their lives. The bomber was never caught, and “for the first time the word terrorism gained currency in the American vocabulary.”

Continue reading the main story

The concept of domestic terrorism flared up anew in 1951, when a “mad bomber” who signed his work F.P. set off a bomb in the so-called whispering gallery of Grand Central Terminal, right outside the famed Oyster Bar. With an uncanny eye for locations sure to unnerve New Yorkers, F.P. set off devices at the Paramount Theater, an old movie palace in Times Square; the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue; the Port Authority Bus Terminal; and in the lobby of Con Edison headquarters. (It turned out that F.P. had a legitimate beef with Con Ed.) After 28 attacks, Dr. Brussel, a Freudian psychiatrist who ministered to patients at Creedmoor state mental hospital, used “reverse psychology,” a precursor of criminal profiling, to identify features of the bomber — his “sexuality, race, appearance, work history and personality type.” Aside from an unseemly fight over the $26,000 reward money, the case was a genuine groundbreaker in criminal forensics.

Continue reading the main story

But enough about the good guys. Let’s get back to the killers. Personally, I am partial to historical legends like “The Greatest Criminal of This Expiring Century,” the man who terrorized Chicago during the 1893 World’s Fair. “The Archfiend of the Age,” to give him another of his many sobriquets, was said to have murdered “hundreds” of tourists who came for the World’s Fair by luring them into his “Murder Castle,” with its many secret passages and torture chambers. In H. H. HOLMES: The True History of the White City Devil (Skyhorse, $26.99), Adam Selzer concedes (a bit reluctantly, it seems) that it’s all hogwash, tall tales aggregated by the newspapers out of gossip and rumor. Although Holmes confessed to 20 murders (and several aborted attempts), he was only ever suspected of a single murder, and those unseen rooms were probably for warehousing stolen furniture. Psychologists and criminologists promptly dismissed Holmes’s detailed confession of his crimes, but his lurid storytelling made for stimulating reading. (“I cut his body into pieces that would pass through the door of the stove.”) And the case continues to fascinate, as indicated by the huge success of Erik Larson’s “The Devil in the White City.”

Let’s end this on a classy note, by returning to Paris during la Belle Époque, when everyone knew how to dress. In THE COURTESAN AND THE GIGOLO: The Murders in the Rue Montaigne and the Dark Side of Empire in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Stanford University, cloth, $85, paper, $24.95), Aaron Freundschuh rings the graveyard church bells for a refined, if corrupt fin de siècle world that passed away with a sigh. When the Paris police prefecture got word in March 1887 of a triple homicide on the Rue Montaigne, he knew what he had — yet another senseless murder of women from the Parisian demimonde. But this time attention had to be paid, because one of the victims, Madame de Montille, was a courtesan belonging to “an ethereal rank” of kept women known for their professional skills and fabulous wealth. The level of butchery linked the killings to a series of unsolved homicides that began eight years earlier. Had Jack the Ripper not made his dramatic appearance a year later, Freundschuh convincingly argues, the courtesan killings would have entered into the historical annals. These atrocities are every bit as disturbing as the Ripper killings, and the images of the victims should be approached with caution.

For that matter, all true crime books should be approached with caution because they lack the gauzy perspective of fiction. But the hazards of the genre are worth it, because for all the imaginative thrills of a tall tale, nothing beats a true story.

Continue reading the main story

♦

What’s a great true crime book for summer vacation?

“In Erik Larson’s adept hands, the story of a long-ago serial killer in ‘The Devil in the White City’ reads like a gut-pummeling horror film. Readers are made to feel unsettled and uplifted.” —Michael Cannell

Continue reading the main story

The post Paris Poisoners and a Pioneering Female Detective: Your True Crime Books for the Beach appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Teju Cole Pairs Text and Image to Explore the Mysteries of the Ordinary

This content was originally published by ROBERT PINSKY on 1 June 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Photo

“Which world?”: Teju Cole

Credit

Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

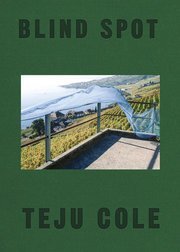

BLIND SPOT

By Teju Cole

Illustrated. 332 pp. Random House. $40.

Teju Cole has composed a lyrical essay in photographs paired with texts, with each set identified by its locale, including — to name only a few — Auckland, Brooklyn, Brazzaville, Hadath El Jebbeh, Lagos, McMinnville, Paris, Queens, São Paulo, Selma, Vals, Ypsilanti, Zurich. Yet Cole’s subject is not variety but what he calls “the continuity of places … the singing line that connects them all.” Unlike tourism, or tourism’s uppercase guide, the Travel Pages, “Blind Spot” does not pursue the spectacular landscape or portrait that epitomizes a destination. Rarely do Cole’s images of streets, doors, mirrors, murals, pavements, interior and exterior walls disclose their specific geographical setting. The terse captions do that. The point here is not the exotic but its opposite: mysteries of the ordinary, attained in patiently awaited, brief flashes. In other words, this is a book about human culture.

The photographic term “flashes” also applies to the method of Cole’s 2012 novel, “Open City,” which arranges its incidents somewhat obliquely, in an episodic rhythm based on psychological discovery rather than adventure or suspense: an introspective picaresque. The novel accumulates intensity by spurning trite expectations — about New York and about the Nigerian central character’s life there as a medical student. Even when he is mugged or breaks up with his girlfriend, the surface of incident is less important than the underlying, ineffable undertones of destiny and character.

Similarly, in “Blind Spot” passages often refer backward or forward to one another, but not with any obvious narrative or discursive rhythm. Often the text glosses the exact instant of the photograph, as when a chance wind lifts some netting for a moment, opening a landscape into human time: “They are with us now, have been all along, all our living and all our dead.” The images are populated with human life, but for the most part that life is implicit: with a notable, climactic exception, there are few faces.

Photo

These choices are deeply purposeful. The abstaining, in texts and photographs, is ardent. In São Paulo, the image shows a dizzy, dense geometry of many-colored city blocks of towers and windows. In the facing text, someone asks the author a question that he says resembled “the sudden realization that a mirrored wall has been double-sided all along.” That question, which Cole gives, characteristically, as “not her exact words,” concerns the unity of all his work around one, unstated problem. In Selma, about 100 pages later, the question recurs: the image shows a flat, barren geometry of a monochromatic street bifurcated by a vivid telephone pole. In the facing text, Cole writes of “a dream in which I am crossing the street and never reach the other side. … I keep deferring my arrival at the destination. The destination is to arrive at this perpetual deferral, to never reach the destination.” Beyond the apparent contrast between density and blankness, São Paulo and Selma, a similarity: that “continuity of places.”

Continue reading the main story

The post Teju Cole Pairs Text and Image to Explore the Mysteries of the Ordinary appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Indigo Reports Record Revenue in Fiscal 2017

This content was originally published by on 31 May 2017 | 4:00 am.

Source link

Driven by sales of general merchandise and ‘Harry Potter and the Cursed Child,’ the Canadian bookstore chain reported record revenue growth for fiscal 2017.

Source link

The post Indigo Reports Record Revenue in Fiscal 2017 appeared first on Art of Conversation.

Summer Thrillers: Daring Escapes and Other Acts of Derring-Do

This content was originally published by CHARLES FINCH on 31 May 2017 | 9:00 am.

Source link

Then her father escapes from prison, killing two guards. Helena immediately thinks of her daughters. She knows which one he would take, she realizes, and this horrifying unbidden thought decides her. “If anyone is going to catch my father and return him to prison, it’s me. No one is my father’s equal when it comes to navigating the wilderness, but I’m close.” The book adopts a plaited structure, with alternating chapters set in the past and the present, the former relating the tale of Helena’s flight from the marsh where she grew up, the latter her return to it to search for the man who raised her.

Two elements make Dionne’s book so superb. The first is its authenticity. There’s a strain in the contemporary American novel (“Maud’s Line,” by Margaret Verble, and “The Snow Child,” by Eowyn Ivey, are recent examples) defined by a knowledge of nature that feels intimate, real and longitudinal, connected to our country’s past. When Dionne describes the swamp maples that make a cabin invisible from the air, or the way one digs chicory taproots, then washes, dries and grinds them to make a coffee substitute, it seems effortless, plain that her fluency has a deeper source than Wikipedia.

The second is the corresponding authenticity of Helena’s emotions about her father, painfully revisited and refined as she tracks him. She has no doubt whatsoever that he belongs in prison, but she doesn’t hate him — or at least, part of her hatred is love. She recalls him putting on his waders every spring, going into the marsh and digging up a marigold for their porch. “It glowed like he’d brought us the sun,” she says. One of her daughters is named Marigold.

Continue reading the main story

In its balance of emotional patience and chapter-by-chapter suspense, “The Marsh King’s Daughter” is about as good as a thriller can be, I think. Take Dionne’s ending, usually the moment when, as E. M. Forster said, a novel’s plot exacts its cowardly revenge. In most such books, Helena’s daughters would come into jeopardy. But this author isn’t interested in feeding us those cheap calories. Nor does she quite grant us the confessional reckoning we wish Jacob would finally give his daughter. Then again, how many terrible fathers — terrible, precious — ever have? Like everything else in “The Marsh King’s Daughter,” the choice feels right.

Continue reading the main story

The title character of LOLA (Crown, $26), by Melissa Scrivner Love, is also in a race to preserve her life, but in a location as different from the cold, unyielding woods of Michigan as possible: gangland Los Angeles at the height of summer.

Continue reading the main story

The book’s plot, which involves a botched money handoff, is thorny — at one point Lola thinks of her choice of which drug kingpin to betray as belonging to some “awful romantic comedy” — but makes the usual basic urgent sense: We want Lola (tough, resourceful, tender whenever her circumstances on the periphery of the drug trade allow her to be) to keep being alive, and not start being dead.

Continue reading the main story

I blazed through “Lola,” a debut as fast, flexible and poised as a chef’s knife. At its best it has the lithe energy of a Lee Child novel, combined with Dennis Lehane’s — or, to step outside of the genre, Stuart Dybek’s — sense of the exhausting intimacy of poor neighborhoods. “What would she have done,” Lola wonders, “if she’d grown up in a two-story ranch house far from South Central? What would she have done if she’d had a mother who defrosted vegetables every night for dinner?” Crime fiction, because its exigencies feel natural, has been our country’s best way of thinking about class for more than a century now.

In its weaker moments “Lola” suffers from a certain teleplay sleekness, picked up, perhaps, during its author’s stints at “CSI: Miami” and “Person of Interest.” To take one instance, Lola, who was the victim of sexual abuse in service to her mother’s drug addiction, spends a lot of her scarce free time trying to protect a girl in an exactly identical situation, a symmetry that feels executive-filtered, false to life.

The book’s ventures into philosophy are similarly inert. (“All people everywhere, rich or poor, skinny or fat, are animals,” we learn. “Looking for a fight. Looking to turn everyone against the weakest.” Blurgh.) But it’s still an unshakably engrossing read, and in Lola and her allies, who trace their connection to the familiar blocks they’ve loved and loathed their whole lives, Love is vibrant and cleareyed, an exciting new West Coast observer.

Like Love, Peter Blauner has taken his turn in the Hollywood churn, writing for the television drama “Blue Bloods,” but somehow, perhaps because he first spent a long career in journalism and fiction, he remains obstinately idiosyncratic in PROVING GROUND (Minotaur, $25.99), his first novel in 10 years. His garrulousness salvages a story that’s only intermittently engaging.

Continue reading the main story

Blauner’s tale involves the murder of David Dresden, an idealistic lawyer with a significant case pending against the F.B.I. He’s shot in Prospect Park, and immediately two people sense deeper machinations — Dresden’s son, Natty, a veteran with PTSD, and a zaftig, astute young police detective named Lourdes, fighting to make it in a department designed without her interests particularly close to its heart.

They converge from different angles on the same possible perp, who is, alas, catastrophically easy to spot. Luckily the people who fall for “Proving Ground” will care far more about its voice, filled with moments of surprising New York stoop-sitting joy. Blauner is a bad-ball hitter — he’ll miss on an easy description, overwriting Dresden’s widow for instance (“a long-backed Park Slope lioness with vaguely Eurasian-looking features”?), but then capture with beautiful easy precision, for instance, a flash of dialogue between cops, who talk skells and Rockefeller time, “flip tin,” banter at each other to signal that they care.

Continue reading the main story

The cynosure of this style is Richard Price, and Blauner shares his intricate gabbiness. But Price’s gift (particularly in “Clockers,” his masterpiece) is partially for invisibility, for the lurk; Blauner is always there, writing his way into every line. It slows the book down. “Lola” is a better widget than “Proving Ground,” better paced, clearer in its stakes. But Blauner’s fable seems truer to its emotional beats, Natty and Lourdes powerfully real in their lucid, disillusioned idealism. In both characters, Blauner returns repeatedly to the book’s truest subject, the inescapability of the past. “Why keep looking back?” Natty asks his therapist, irritated, when he’s on the verge of solving his father’s murder. “Because that’s probably where the answers are,” she replies.

Continue reading the main story

New York, drawn so lovingly in “Proving Ground,” has always been the city closest to matching Baudelaire’s definition of beauty: the infinite within the finite. IF WE WERE VILLAINS (Flatiron, $25.99), a melodramatic but satisfying debut by M. L. Rio, takes as its subject the only infinite writer we’ve had yet, no matter how hard Karl Ove Knausgaard pushes — Shakespeare, of course.

The book is set across a school year at Dellecher Classical Conservatory, a Midwestern analogue to Juilliard, “less an academic institution than a cult,” where seven senior actors immerse themselves with radical intensity in both one another and the works of the glovemaker’s son from Stratford-on-Avon. One of their passionately close-knit number, Oliver, narrates their tale, years later. The twist is that he does it just as he’s getting out of prison.

Continue reading the main story

The novel’s first third is plotted ingeniously, as we wonder who might die. The bully during “Julius Caesar”? The seductress during “Macbeth”? At last a body falls. The rest of the novel is a whodunit, occasionally clumsy but entertaining. The solution, when we learn it at last, proves clever, and as the book ends the six remaining students, older and scattered now, move tentatively toward the idea of reunion.

Rio’s model couldn’t be clearer: “The Secret History,” by Donna Tartt. But this is not that eerie, half-mad novel; it’s too nerdily good-natured, and too nerdily (and winningly) in love with Shakespeare. Every page is scattered with his words, which the students toss at one another as easily and endlessly as a shared second language. There’s a kind of elation in seeing both famous and obscure phrases from the plays plucked and resituated, the effect first-rate — distancing, salutary.

Continue reading the main story

“If We Were Villains” is, then, a readable, smart, pretentious, youthful book, at once charming and insufferable, at once good and bad. It’s steeped in the hysterical significance the young ascribe to their own lives. Middle-aged readers often tend to scorn this sort of hothouse fictional narcissism. (I know, having written a novel about an American at Oxford that everyone younger than 31 seemed to love, and everyone older than 31 seemed to loathe.)

But perhaps there’s something forgetful in that rejection. “We … looked at each other with wide, unguarded eyes,” Oliver says in the hovering moment before a kiss, and this is a book with wide, unguarded eyes. Most of us looked at the world that way once: not so happy, yet much happier.

Rio, however clunky her book’s characters and plotting can sometimes be, captures that, the exhilarating dummy immortality of youth. She may become a more adroit writer, but she won’t become a younger one. That’s a trade that people with more experience can be too sure is in their favor. As Joan Didion observed, it’s best “to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not.”

Continue reading the main story

The protagonist of William Christie’s panoramic, smart, hugely enjoyable thriller A SINGLE SPY (Minotaur, $25.99) does nothing but keep on nodding terms with who he used to be, because he knows that keeping a careful genealogy of his identities is his only chance of staying alive. His name is (sometimes) Alexsi and he stands out in his orphanage for his resourcefulness and instinct for escape; these gifts, after a brief interlude running guns in Iran, lead to his recruitment as a Russian spy, just in time for World War II. Hurray.

Continue reading the main story

That recruitment is the fulcrum of “A Single Spy,” but despite being a war novel it’s more “Odyssey” than “Iliad,” with its hero on the perpetual run. Alexsi twists out of countless dead ends, and Christie does, too; each time his tale seems to be drawing into a cul-de-sac, he pulls it sharply and headily in some new direction, from Azerbaijan to Moscow to Germany, Alexsi shifting between passports, killing easily when he must, trying to balance the ruthless spymasters who would be delighted to sacrifice his disloyalty to the state. “Ugadat, ugodit, utselet,” Alexsi tells himself. “Sniff out, suck up, survive.”

This is a subject too little acknowledged in thrillers, the gift that some people have for life, for going on living. Because of his (marvelously credible) character, Alexsi’s survival seems both impossible and inevitable. The spy novel keeps trying to save the world, but the beauty of “A Single Spy,” what makes it a truly great example of a genre that has not lately been very good at all, is how closely it sticks to Alexsi’s crucial, statistically meaningless survival, the slight cant of his personhood.

It reminded me in this sense of “The Orphan Master’s Son,” by Adam Johnson, another novel about a state’s unrelenting effort to deindividualize its members. Of course, the problem with humans is that the largest unit they come in is one; otherwise, totalitarianism would be a breeze. Alexsi’s stubborn defiance of any state’s rules — he betrays Russia to Germany to England to Russia to England, betrays everyone but himself — captures a thread that runs through all five of these worthwhile novels, the idea of holding out against dishonesty, slipping through its maze to remain true to one’s self. Who knows how relevant that example may become in the next 1,250 days?

Continue reading the main story

♦

What are your favorite thrillers for the beach?

“At the top of my list is John Grisham’s ‘Camino Island,’ a ‘trouble in paradise’ tale in which a central character is a bookseller. Noah Hawley’s ‘Before the Fall’ takes off after a mysterious plane crash. I’m also a fan of Y.A. — E. Lockhart’s ‘We Were Liars’ has a twist most readers won’t see coming.” — James Patterson

Continue reading the main story

The post Summer Thrillers: Daring Escapes and Other Acts of Derring-Do appeared first on Art of Conversation.