Sarah Vaughan's Blog, page 5

September 23, 2015

Why we bake: patisserie.

Compared to many of my fellow novelists, the research could hardly be described as arduous: making choux pastry and deliberately allowing the mixture to catch. I was trying to describe a baking disaster and had convinced myself the only way to do so was to act it out. The smell of burnt sugar filled my kitchen as the pan’s sides burned, and lumps of egg and cornflour congealed into sweetened scrambled eggs.

As The Great British Bake Off enters its patisserie week, I was reminded of this moment, which came as I finished my novel about why we bake. Despite my mother excelling at that 1970s dinner party staple, profiteroles, and my making a mean crème pat, I had never attempted choux. But writing The Art of Baking Blind, a novel partly inspired by the GBBO, taught me to push my culinary boundaries. Forget method acting, this was method writing: immersing myself in a world of melted butter and sugar; of egg whites whisked into stiff peaks, and rising dough. Cocooning myself in the scent of warmed cinnamon and nutmeg; learning how to make a patisserie at the heart of my novel - the tarte au citron.

Mango coulis, citron crème pat, ganache, choux, a galette base: patisserie for the launch of the French edition of The Art of Baking Blind, La Meillure d'Entre Nous.

I first came up with writing a novel about why we bake as I made sponges and gingerbread men with my small children. For me, baking was the perfect way of doing something creative while proving that I was a good mum. If that sounds extreme, I’d given up a job as a senior reporter and former political correspondent on the Guardian to freelance and be a stay-at-home mother. Used to writing every day, I wanted to mix and churn, to beat and whisk, and crucially to come up with something delicious at the end of it. Because that way I was not only achieving something but I was showing my children – with my roast chickens and homemade stocks, soups and risottos as well as my cakes and biscuits – just how much I loved them.

I realised I was over-investing my baking with emotion when I took a tin of homemade chocolate chip cookies, made with my four-year-old, to some new friends on a play date. “Talk about showing us up!” laughed another mother, her tone distinctly brittle. “Can’t you just bring a packet of jammy dodgers like everyone else?”

I began to think about why I bake and what motivated other bakers I knew: the mums decorating exquisite cupcakes for the school fair; the stick-thin mother who had heaped my plate with birthday cake as a child; the contestants who put themselves through competitions like GBBO, who were willing to spend hours spinning sugar or constructing gingerbread houses they knew would immediately be demolished. Because I was sure that our obsession with baking wasn’t just about nostalgia in a time of recession – though that may be part of it - but about the fact that we can we can work through all sorts of emotions while we create with eggs, fat, sugar and flour.

Profiteroles sold in Le Marais, Paris; filled with rose water or chocolate crème pat and sometimes gilded with gold leaf.

With this in mind, I used the characters in my novel to illustrate different reasons we bake. For Jenny, a housewife and mother whose daughters have flown the nest, it remains a way to prove she loves her family, even if they no longer need her. But it’s also a habit, a means of working through her emotions, and a way of connecting with a happier past.

For Vicki, who remembers her childhood kitchen as “a cold room…in which she ate supermarket quiche and watery iceberg,” baking with her son is a means of providing him with the loving childhood she lacked. Constrained by motherhood, the baking competition also allows her to do something creative and to carve out some time for herself.

For Mike, a widowed father, baking not only provides some validation but is therapeutic, while for Kathleen Eaden, the cookery writer whose 1966 cookbook, The Art of Baking, inspires the baking competition and informs the novel, baking is such an extension of her personality that what and when she bakes mirrors her mood and reflects the plot.

And then there is Karen. For if most of the novel’s associations with baking are positive, for her there are more sinister connotations. She doesn’t bake because she is frustrated or needy, like Vicki, but because she is a perfectionist for whom baking is the ultimate means of control.

Launching the French version of The Art of Baking Blind, La Meillure d'Entre Nous, in Paris earlier this year, I kept being reminded of this, my most troubled, character. For patisserie is the form of baking which, more than any other, demands self restraint and an obsessive attention to detail.

I could see this in the patisserie created for the Livre de Poche launch: delicacies involving passion fruit gel on mousse au citron with sesame tuile and black sesame crème pat, or citron crème pat and black sesame shortcrust, topped with a tiny, sesame-dusted meringue. It was evident in the shops specialising in exquisite profiteroles or sables biscuits; confections sandwiched with mango, vanilla, chocolate or citron crème pat, and laid out beneath glass cabinets as if they were expensive jewellery; and even in the blowsy displays of more traditional patissiers: the glossy tarte aux fraises; the rich curls of dark chocolate; the plump religieuses; the dinky macarons and expertly-constructed millefeuille.

I spied these sentiments, too, in the readers who discussed why the bakes in my novel were not as creative - or as accomplished - as those in their patisseries; or who gently pressed me to taste their creations.

One reader had spent the day making 100 macarons in seven different flavours - including blackberry, citron, pistachio, chocolate and raspberry - for a friend's macaron pyramid birthday cake; a feat she pulled off while racing through 100 pages of my book. "You're a good friend," I commented as I bit into her tiny, light-as-air pistachio creation and listened to the coos of other women doing the same; and she shrugged, in self-deprecation. "It was nothing." She had pulled off the ultimate trick: patisserie that was perfect but that claimed to be effortless.

Her answer, though, also conveyed the motive that I think is at the heart of most baking. For while we may bake out of neediness, because we're frustrated, competitive or suffer from what French Elle describes as "the tyranny of slimness", most of us bake "in the spirit of generosity" as the BBC's Martha Kearney, herself the winner of the Comic Relief Bake Off, has said.

Or as Kathleen Eaden declares in my novel: "There are many reasons to bake: to feed, to create, to impress; to nourish; to define ourselves; and sometimes, it has to be said, to perfect. But often we bake to fill a hunger that would be better filled by a simple gesture from a dear one. We bake to love and be loved."

September 18, 2015

Ladies finger cutters and a fondant gusset: the secret of GBBO's success

It was a question the author and journalist Allison Pearson knew might be seen as "heretical." Has this series of The Great British Bake Off become just a little bit dull?

Had the "perfect soufflé of primetime patisserie run out of puff?" she asked. The contestants bland; any sense of suspense or jeopardy gone. Had it not only deflated this year but never really risen at all?

The Telegraph columnist, posing the question last week, was absolutely right about the lack of suspense. There's been no Bingate this year - the carefully-edited moment in which a Baked Alaska was taken out of a freezer and left to melt by a rival contestant. Ian's reign as star baker was becoming wearing, and, before Wednesday night when the contestants were culled to five, there was not one ounce of jeopardy at all.

And yet for me, and I suspect many of the ten million viewers who still tuned in this week, suspense isn't the reason we watch this primetime success. We view it for the characters as much as any competition or bakes: trying to fathom what motivates them to spend three hours in a tent constructing a Victorian fruit cake decorated as a tennis court.

Why would a prison governor discuss, in all earnestness, and without any sense of irony, the importance of fashioning a bread lion - and not a dog? What leads a gentle male nurse, on the edge of tears, to confess to over ten million people: "My father was a general. Failure is not an option." And why does a young mother-of-three, dispelling stereotypes by baking in a headscarf, and with a superlative array of facial expressions, admit, her voice shaking with relief and a sudden shot of self-belief: "I'm never proud of myself but I'm actually really proud." Moments like these - swift glimpses into the deepest recesses of the contestant's psyches - are the point of Bake Off:

I'm intrigued as to why firefighter Mat, who grew up in a house "where we didn't have dinner parties; don't think my mum ever made a vol au vent" thinks he can wing it in a competition in which he didn't practise for the latter stages, never thinking he'd get there. ("Don't let a fondant tennis court be the end of it," admonished Sue. And yet it was.) Or why bluff prison governor Paul, a man who shrugs off criticism like the proverbial duck in water, wants to fashion a fondant bikini, with gusset, or sculpt an apple into a swan. ("I learned it in a day. It's what I like doing. The arty side of things," he told Mel.)

Then there are the bakers who are so perfectionist they make Heath Robinson style gadgets with which to perfect their creations. Last year it was Nancy, who produced a guillotine to slice her jaffa cakes in the first episode - and went on to win. This year, it's Ian, who bakes bread in a flowerpot, fashions steel to create leaves, and this week produced a ladies finger chopper.

"Each of my ladies fingers is exactly nine centimetres long," he explained, with a somewhat wolfish grin. Coming after his Road Kill pie, inspired by kill that's been "bumped not flattened", this sounded not just exacting but slightly sinister.

Of course, these eccentricities are gentle. Bake Off remains a warm, comforting bath in a troublesome world. An hour of unapologetic escapism in which people are largely nice - although, over half way through, some more overt rivalry is finally, thankfully, coming to the fore.

It was there in Nadiya's one-handed clap against her bicep when Ian constructed a show-stopping Victorian crown and her less-than-effusive "very good". (The sort of "very good" you could imagine her giving a child who consistently draws better than its younger siblings - but still wants praise.) It was there in Flora's shake of the head, arms crossed like a curmudgeonly gossip, and her or Nadiya's: "Flipping heck!" (It could have been either of them.) We could see it in Mat's flash of irritation - "Aww, you've twisted it" - when Paul, trying to help him ease his Charlotte Russe onto a pedestal - apparently exacerbated the split. And in Ian's barely-perceptible tic of disappointment - a slight tightening of the jaw - when anaesthetist Tamal, beautiful, and distinctly Eeyorish after daring to hope he might do well and then failing last week, finally became star baker.

Writing in yesterday's Telegraph, last year's winner Nancy revealed that "once you get to half way it's a completely different atmosphere. It becomes more intimate." Much of the set is cleared away and the crew scaled down; contestants know the production team, the judges, and each other.

For the viewers, things become more interesting, too, for we know the remaining, more-focussed, bakers well enough to care. We're attuned to the tensions, as well as to their loyalties - or lack of them. We can predict that Nadiya will look at Mat in utter disbelief when he says he's put his icing tennis rackets in the oven.

"Oven?"

"Yeah."

"Were we supposed to put it in the oven?"

Or that Mat, in those few seconds of horrified disbelief, will know, as we do, that he's going home that week.

In fact, that moment encapsulates the GBBO style of suspense. Momentary and understated but still poignant and telling in its own small way.

It's the quarter final next week. Here's to more of these vignettes.

September 15, 2015

The Art of Baking Blind: nestling up to Poldark.

In the month since The Art of Baking Blind came out in paperback, I may have put this photo on social media more than once. Not just because I'm proud of that WH Smith chart position but because it makes me want to laugh out loud.

This is probably the only chance I'll get to snuggle up to Ross Poldark (Demelza's just out of the picture, to the far left; I've rather pointedly edited her out.) I've also been found nudging Marian Keyes and Nick Hornby in Waterstones:

And squeezed next to one of my literary heroes, Sarah Waters:

If it seems arrogant or self-indulgent posting these shots, then I do so knowing that my position jostling them is likely to be short-lived. A month after publication, and my novel is no longer at the front of my local Waterstone's - although it is proudly displayed in my local Waitrose, Tesco, Asda and Morrison's (and seemingly out of stock on amazon). And so, as I embark on my third book, I am drawing on these photos to write harder, faster, brighter. Here they are: proof that I once did it; that I might - perhaps - do it again. My avocado spine is aligned with other authors. Proper authors that people have heard of. Look, I tell myself: it's really me.

When I wobble - as I know I will because self-doubt seems intrinsic to writing and to my psyche - I will also remember the gorgeous reviews I've received, and the blog posts written prior to publication day. I've collated my blog posts, partly to remind myself of the flurry of activity; and partly because I want to preserve the optimism and excitement of writing my first novel in some way.

There was a debut author spotlight interview for Shaz's Book Boudoir, here, and a Q and A for the Reads & Recipes blog, here. I wrote about my experience of being an author for Off the Shelf Books, here; and a feature about why we bake for reviewer Chicklit Chloe here.

For Good Housekeeping magazine, I blogged on the different types of baker, here, and for women's fiction website novelicious, I wrote a literary love letter to Kate Atkinson, click here. I have also written for novelicious about my book deal moment and my top writing tips, as well as being interviewed, here. I wrote about the allure of baking and offered a carrot cake recipe. Finally, I shared a recipe for gingerbread men on Alba in Bookland's blog, here.

For now, this flurry of publicity is over as I wait for the copy edits of my second novel, That Summer at Skylark Farm, and start on my third. The editor who bought both books has been headhunted, so I'm writing without a contract: crafting something with which to surprise, and hopefully delight, my publishers. If the prospect is exciting, it's also daunting. But I have two books written, now; and these photographs to buoy, chivvy and inspire me. There I am; nestling up to Poldark. Yes, it's really me.

August 12, 2015

Happy paperback publication day to The Art of Baking Blind

So, after months of anticipation it's finally here: the day this little beauty hits the shelves as a paperback and hopefully finds a wider reading public. This was the present delivered earlier this week and I have to admit to giving a private squeal in my kitchen when I opened the box of embossed and stickered copies of my book.

All those discussions about fonts and colours and levels of embossing have been worth it for a photo doesn't do these novels justice. You need to stroke the cover and peek inside to appreciate the level of effort the Hodder design department has gone to to make this look enticing. As pretty and exquisite as a French macaron, the hope is it will prove just as irresistible.

Of course we can't know how it will sell but, thankfully, the supermarkets and shops seem to have liked it. Today, The Art of Baking Blind will appear on shelves in Waitrose, Tesco, Morrison's and Asda; it'll be in the WH Smith paperback chart, and on tables in WH Smith Travel; and there will be copies in Waterstone's and independent bookshops, too.

The novelist Patrick Gale has just tweeted pictures of a box of copies of his 17th novel, A Place Called Winter. The excitement never fades, he said. I can't imagine writing 17 books but I can well understand that that tingle of exhilaration never truly goes away. Now, I just have to hope that potential readers feel a smidgeon of the excitement I do.

June 26, 2015

On the lure of the old. Or why the past keeps pricking at me.

I found these vintage baking accessories in a Parisien salon du the, and while I would usually be lured by the patisserie, these were the items that drew me in.

My first novel, The Art of Baking Blind, features a fictitious 1966 recipe book, and I could see its author carefully weighing ingredients decanted from such jars before concocting her millefeuille. Kathleen Eaden attended the Le Cordon Bleu before my novel began - and, as I feasted on these covetable kitchen accessories, I imagined her life outside my pages: a late teenage rebellion; an affair with a pastry chef; late nights and early mornings fuelled by coffee stored in tins like these:

Perhaps it's no surprise then, that, as a writer, I covet vintage things. Despite knowing that most "preloved" finds are tat, I'm drawn to old china, books, furniture: anything with the potential to trigger a story.

I live in an eighteenth-century cottage that we renovated. And as we opened up chimneys and pulled at floorboards, it kept revealing secrets; glimpses of others' lives. Who hid that toy soldier up the chimney? Or buried the 1930s advert for slimming aids? Or the glass bottle labelled arsenic in the garden? Who owned these pieces from the past that kept whispering their tales?

Then there are the vintage finds I’ve picked up at jumble sales or local auctions: a delicate coffee cup and saucer, etched in gold leaf; mismatched crockery; a 1950s pitcher with “Jug” somewhat unnecessarily stamped on it. A child’s eighteenth-century rocking chair, bought for £70, whittled in oak by a father, and revealing a name graffitied by a small girl: Ivy. A French-polished writing box, belonging to a grandfather who took poetry books to war and lost them when captured on Kos; my grandmother’s locket, which I can never open without catching the scent of her.

I never thought I would write historical fiction but it now seems inevitable that the past would worm its way into my books. "The past kept pricking at me," explains LP Hartley's narrator, in The Go-Between, and it's a quotation that could preface many of the novels that fascinate me and that I go back to.

We are the sum of our past, as well as our present and future, which surely explains the burgeoning interest in genealogy and the existence of programmes such as the BBC's You Do You Think You Are? as well as our nostalgic hankering for vintage brickabrac. "The past is not a package one can lay away," as Emily Dickinson said. And we see that throughout our culture - from watching Downton to being fascinated by World War II to visiting National Trust houses. And yes, to purchasing accessories inspired by the 1950s or 60s: those Tala measuring jugs; or Keep Calm and Carry On cards, which work precisely because we know they are a play on Kitchener's iconic poster. Because we share that history.

When writing about a farm in north Cornwall, run by the same family for six generations, it seemed obvious, then, that I would draw on my own family's past and in particular the stories my mother told me of spending her childhood summers on a Cornish farm.

But though my her recollections fed into it, I needed a prop: some tangible evidence that would sit on my desk and inspire me as I pushed through the third draft, and the fourth, fifth and sixth. Something that would whisper its past to me, when I was feeling sluggish; that along with my photographs of the area, would prompt me to think: "what if?" and, "and then what?"

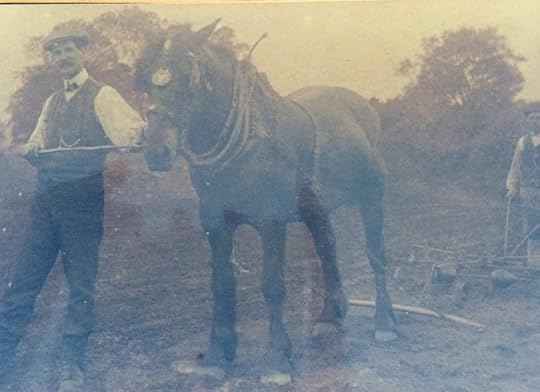

This sepia photograph does just that:

It shows my great grandfather, Matthew Henry Jelbert, hoeing mangolds on Trewiddle, his farm, just outside St Austell. He looks slightly shy yet rather proud as he leads his shire horse and the plough. Dressed for the camera, he sports a tie, white shirt and collar, gold fob watch and luxuriant moustache. His farmhand waits discreetly, for this is Matthew’s moment, even though the horse, the most expensive animal on the farm, dominates the picture.

Matthew Jelbert was born in 1880 in Newlyn East, towards the tip of Cornwall, seven miles from Truro and Newquay. He died in 1970, two years before I was born, yet both he and his farm - or rather the tales of them - were a vivid part of my childhood.

My mother spent each summer there in the Fifties, and those weeks helping with the harvest were the happiest of her childhood. Her father, Maurice, was a Methodist minister, but there he could revert to being a farmer’s boy and she was freed of the constraints imposed on a minister’s daughter.

She would run wild with her cousin Graham, eighteen months younger than her but, growing up on a farm, more worldly-wise. They would climb trees; blow birds’ nests; hide in the stooks of corn; play doctors and nurses under the rhododendron bushes. A chalky stream ran at the bottom of the field, from the china clay pits, and she believed that it was milk, and Trewiddle, heaven. For a child expected to go to church three times on a Sunday, it was quite literally the land of milk and honey.

Trewiddle held such a strong sway on me as a child that I named my doll’s house and its connected farm after it. And when I came to write my novel, about a granite farmhouse on a remote stretch of the north Cornish coast, my mother and her cousin’s memories, and the photos of the farm, weaved their way in.

Great grandpa Matthew watches me, now, as I type.

My past is pricking at me. I am taking liberties with it but hope I do it justice.

June 18, 2015

Happy Publication Day to the German edition of The Art of Baking Blind.

The Art of Baking Blind is published in Germany today as Die Zutaten des Glücks - or the rather lovely The Ingredients of Happiness. And as well as this being an opportunity to bake celebratory cheesecakes and black forest gateaux, it's made me contemplate fonts.

For while my German publisher Bastei Lübbe has used the same cover as Hodder, it departed from the original in using a different font for the sections in the past and a special letter-writing font for the one letter in the book. I love the changes but it's made me think about how we view the typography of novels.

When I submitted The Art of Baking Blind to publishers, I used italics for the quotations from The Art of Baking, the vintage cookery book whose bon mots top each chapter. But I also used italics for the flashbacks that intersperse the present day plot, which concern the cookbook's author Kathleen Eaden and run from 1964-66.

I wanted to clearly convey that these sections belonged to a different time and also differed in style, being exclusively from Kathleen Eaden's point of view. They were the most intensely emotional parts of the book and although they complemented the present day plot could be read as an individual story.

I hadn't considered, however, that while italics are routinely used to convey direct inner thoughts - most explicitly in a novel like Gone Girl - or for lists or letters, they signal to some readers that they can be skipped. The same could be said for any fonts used for meta-fiction. My 10-year-old, rereading the Harry Potter books, leaves out The Daily Prophet sections, the parts written in a heavy newspaper typeface. "They slow up the story," she explains. "My friends do it, too. We go back and re-read those sections if they're not explained later and we need to fill in the gaps."

None of this had occurred to me before Nina Stibbe, the bestselling author of Love, Nina and Man at the Helm, was kind enough to read a proof of my novel and pointed out the risks of sustained italicised sections. "I loved it but there's just one thing I don't like," she said. "The italics. You don't want people to skim them. Could you think about getting them changed?"

She was so persuasive that we reverted to the usual font with the sections being headed Kathleen. Bastei Lübbe didn't want to use our formula but came up with an excellent alternative: not using italics but a font which differs distinctly from the Times New Roman or Cambria we are used to seeing as the usual types. It's a technique also used recently in Marian Keyes' bestselling The Woman Who Stole My Life, in which the present day sections are in a more modern font to the back story set four years previously.

Bastei Lübbe also used a letter-writing font for the crucial letter on which Kathleen's story turns, which conjures up the era in which it was written, 1972:

As Iris Gehrmann, editor of fiction, explains: "We chose a different font for the Kathleen passages to distinguish her perspective from those of the other characters in the book. And the special handwriting font used for Kathleen’s letter at the end of the book is supposed to emphasize the very personal character of the document and its nostalgic flair."

All of which makes me wonder if I've become rather conservative not just in the way in which I react to fonts when reading but when writing. I tend to write in Times New Roman or Cambria, liking the implied authority and the way in which it is similar to the Sabon MT used by Hodder for my novel. In other words, the fact that it looks like a "proper" book.

Some authors switch to different fonts to edit: the change flagging up errors or prompting them to read in a fresh way. "I change font when I'm line editing. I think it helps me to spot errors more easily if I'm staring at a different typeface," Joanna Cannon, author of The Trouble with Goats and Sheep, to be published in the New Year, explains. That works for me but an experiment in writing in Helvetica this week took me way out of my comfort zone. Nothing that I'd written read or sounded right.

Perhaps I could learn from my seven-year-old who enjoys books which eschew the formality of a traditional font or subvert it - such as Andy Stanton's Mr Gum books, in which smudged fingerprints or decreasing and increasing font sizes pepper the page - or which reject the authority of a typed text and appear to be handwritten. "Why do you enjoy the Wimpy Kid books so much?" I ask my boy, as he pores over the latest instalment after reading Tom Gates. "Because there's more space around the words," he explains as if it is perfectly straightforward. "They're easier to read."

It seems I may have been too precious in my attitude to fonts. I tweet Marian Keyes to ask her about her use of them in The Woman Who Stole My Life and she quickly gets back to me. (She's fiendishly good at and prolific on twitter.)

"Why don't you play around with those available to you and see what ones appeal?" she asks - opening up all sorts of future possibilities. "Have fun with it."

May 28, 2015

On Cornwall and colour. Or the importance of a sense of place.

The author David Nicholls wrote eloquently in The Guardian on Saturday about the importance of visiting the places he describes. In a world in which we can click on google earth to research a spot, he argued for the need to visit the locations in which he set his fiction. I couldn't agree more, and as I read the article was en route to Bodmin moor - a 700-mile round trip from my Cambridgeshire home. A small part of me wondered if this was the ultimate in procrastination. Having come back newly inspired, I only wish I'd returned before.

My second novel is set on a farm in north Cornwall, an area I know well having holidayed there each year since I was a child. But there's a section based on the moor and though I've driven over it each year and taken two trips down there in the past 12 months to interview octogenarian farmers and visit its airfields, I hadn't explored it all.

One of my characters embarks on a quest to find a half-remembered farmhouse and I couldn't get these scenes quite right, sitting at my desk at home. I hadn't captured the peculiar claustrophobia of high-banked hedgerows or of tiny villages hidden in the folds between tors. Nor was I sure about the smell: damp grass; musky bracken; honeyed gorse? My character, an intrepid 83-year-old, gets lost, and it was clear I needed to do the same as her.

And so I did. For it's hard not to become disorientated when you're relying on signposts that turn in contradictory directions and interpreting a Cornish mile as, well, a mile. And then the mist came down. A mizzle that made it impossible to see the tors I was searching for; that seeped through my trainers and into my bones; that reminded me of quite how bleak and inhospitable any moor can become.

Daphne du Maurier came up with the idea of Jamaica Inn when she got lost in the mist while riding - just a few miles from where I was. And as I climbed out of tiny Blisland towards St Breward - the area in which Poldark's farmhouse in the recent BBC TV series was filmed - I became similarly disorientated by a visibility that, at best, was poor. Incapable of seeing any farmhouse, or even the track in front of me, I had to stop still. It was just me, the relentless rain, and some Highland Cattle grazing amongst the gorse.

I had wanted atmosphere; a sense of place that was almost tangible; images which would fill my notepad and fuel me as I completed this tricky draft. And here it was. Shrouded in the mist, I scrawled furiously and, when it lifted, found that other famous du Maurier moorland setting, Altarnum.

The picturesque village clustered around an imposing granite church where her vicar caricatured his flock as sheep, who hung on his every word. The air was scented with wild garlic; the hedgerows stuffed with greater stitchworth; bluebells; buttercups and red campion. Mallards waddled towards allotments; rhododendrons bloomed. There was even a tiny village hall, fringing a brook that, yes, really did babble.

It was time to head out. Back to the wildness of the open moor. To an area at the heart of Cornwall and at the emotional tipping point of my novel.

It's an expanse that brings back painful memories for my 83-year-old. Thanks to my return trip, I'm a little more confident about describing her experience.

May 5, 2015

Happy US publication day to The Art of Baking Blind.

My novel about why we bake is published by St Martin's Press today - and it's a surreal but wonderful feeling: knowing that my book may be being picked up in bookshops so far away.

St Martin's have also asked me to come up with some reading group questions and I found them a joy to write. Preoccupied with the redraft of my second novel, it was a delight to turn back to my first one and to lavish a little attention on it. I hope they prove useful. (And if any US readers have recipes for typically American bakes - pecan pie, pumpkin pie, whoopie pies perhaps - I'd love to hear about them.)

Reading group questions: (Note: spoilers.)

1. Blind baking is a technique for ensuring a perfect pastry case yet, as Jenny muses, "so much can go wrong." The impossibility of perfection is a major theme in this novel. Who, in your opinion, is the character that personifies this trait most clearly? And what lies behind the "be perfect" compulsion exhibited by many women.

2. The germ of this novel came when I started baking with my small children. At the same time, I noted the competitiveness of mothers running school cake sales. Is our interest in baking an expression of a hankering for a simpler, gentler - and perhaps fictitious - time? Or is it about a need for validation particularly among highly-educated, stay-at-home mothers?

3. At the heart of the book is the idea of family. For most of the women, baking or cooking represents the idea of "home" or an idealised home. Why do we invest food with such significance? And what do you think of the characters in the novel who fail to perceive food in this way?

4. Food can also be about control, as exemplified by Karen. What do you think of the portrayal of disordered eating in the novel? Is the portrayal sympathetic - do we understand Karen's behaviour?

5. "Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold." The Yeats' epigraph is recalled by Jenny as her sponge curdles and she thinks of her disintegrating marriage. Where else is baking used figuratively to represent personality traits or to mirror a character's experience?

6. Many of the women in the novel are struggling with a change in their lives and it's this dissatisfaction that leads them to apply for the competition. Jenny has lost her old role of wife and full-time mother; Karen is struggling with the idea that her body is ageing Vicki is struggling to adapt to being a stay-at-home mum who may only have one child. Only Claire - whose mother applies on her behalf - is not at such a crossroads. Does this make her a less dynamic; or less sympathetic, character? If not, why?

7. Are there any characters you found unlikeable? If so, why?

8. Did you expect Kathleen's story to end as it did? Did you find that satisfying?

9. In my own family, we have passed down favourite recipes. What are yours and is there an equivalent of an Art of Baking in your life: the culinary Bible that has shaped the way you bake?

April 27, 2015

On why redrafting a novel is like doing your music practice

My ten-year-old is practising for a piano exam and finding it tricky. The Scarlatti Minuet is half-remembered: the bass line forgotten, the fingering more fiddly than before. She plays a couple of dramatic, minor chords then curves off the piano stool balletically. "I'm playing something else," she insists, as she hangs upside down.

And so she starts to learn an alternative piece: a perky Allegro by Clementi. C major and its related G major where the Scarlatti was C minor; a far easier to manage 4/4. Her fingers fly across the keys; the perfect cadences so much more automatic than the Scarlatti's dissonant, imperfect ones.

Her piano teacher wants her to persist with the more complex piece: the sad little melody that fills my head long after I've forgotten the anodyne, jaunty Clementi. And yet, to get it right, she will need to take it apart. She must rethink the fingering; make the rhythm precise; get the dynamics, the phrasing, the odd misremembered note absolutely secure.

I've been thinking a lot about this this week as I've plodded on, redrafting my second novel. For, panicked about my deadline, and knowing it wasn't right but not knowing how to fix it, I opted for a bit of Clementi: throwing bright jauntiness and some basic C major at a tale with a far darker heart. Luckily my clever editor was having none of it. She saw my discordant novel for what it was: a draft in which one timeline - the bass, if you like; or the story that's set in the past - moves resolutely into a minor key - while the treble, or the present day story, insisted on chirping along in its major key, tone-deaf and oblivious to the darker, more interesting rumblings. Imagine playing two hands of the piano in different keys and that's effectively what you had.

Persisting with the Clementi-like plot was not an option and so I've been doing the equivalent of relearning the Scarlatti: though in my case this has meant not just developing characters and darkening plot strands but chucking out and rewriting 30,000 words. Interviewed by Rebecca Mascull last week, I talked about how I'd drawn up a grid for my first novel and seen the different plot lines interweaving polyphonically, like a Baroque counterpoint. This novel has a different structure, with distinct, more equally balanced past and present stories. I've worked relentlessly on the bass line - the past plot - and now it's the turn of the treble - or the present - to sing just as sweetly but with more melancholy, more light and shade, than before.

For getting this second novel right matters immensely and so I push on, worrying away at the rhythm of paragraphs and the freshness of the imagery; checking that a character is psychologically consistent. Fretting about pace; and tension; and balance - just as I once practised my flute obsessively, for hour after hour.

My daughter is back at the piano stool, scrutinising the Scarlatti. And tentatively, she plays first the right hand, then the left one. Rethinking, relearning. Figuring it all out, once more.

April 14, 2015

On patisserie and Parisien perfection: or my Livre de Poche book launch.

When I started writing The Art of Baking Blind, I was so preoccupied with the British obsession with baking it didn't occur to me that it might appeal elsewhere. Which was pretty blinkered, I realised this week, as I spent three days in Paris promoting the French edition of the novel - or La Meillure d'Entre Nous.

I hadn't been to the capital for ten years, and had forgotten that every street seems to boast not just one, but two or three patisseries or salon du thes or boutique shops selling just a few choice profiteroles or macarons. These weren't just shop windows filled with garish blasts of colour - the vibrant reds of a giant tarte aux fraises; the eggy yellow slabs of clafoutis; the rich curls of dark chocolate - such as those seen here:

These were more like exquisite jeweller's shops, with the wares laid out beneath glass cabinets - and the prices so high, one hardly dared to ask. Shops like this one in Le Marais, which sold only profiteroles - some flavoured with rose water and decorated with gold leaf:

Or Bontemps, perhaps 100 metres away, which sold exquisite sable biscuits sandwiched with mango, citron, vanilla or chocolate creme pat - and showcased its flans behind vintage duck-egg blue cabinets and on antique plates:

Little wonder, then, that when Livre de Poche held an evening for bloggers - or blogeurs - in Colorova, a stylish patisserie/librarie in the Jardins de Luxembourg area, a good 25 of them turned up. Even though the weather was glorious - a heady 21 or 22C - and the parks were crammed with Parisiens basking in the first real heat of spring.

They listened attentively as my publisher, Veronique Cardi, enthused about the book and I read a speech, explaining the novel's genesis and themes, that I'd prepared in French. And no one looked disdainful as I fumbled my way through their questions, mixing my grammatical constructions and sometimes turning to the novel's translator, Alice Delarbe, when the vocabulary defeated me. Why were many of the men unsympathetic? (Necessary dramatically); Why were the cakes technical and not as creative as French constructions? (We're not as good at baking as you; to which they nodded.) Why was I obsessed with motherhood? (I'm not obsessed; but I found it a profound experience. It's more women in general - their conflicting needs and roles; and the pressures they impose on themselves - who fascinate me.)

Talking to Alice Delarbe, the novel's translator, and, second from left, the director of Livre de Poche, Veronique Cardi.

It was a real joy to hear readers' takes on the novel; and to be told by one, for instance, that it conjured up memories of a patissiere grandmother and moved her in a way no novel about food had before; or by another that she didn't usually read "girlie books" - "Do you mean women's fiction?" I asked, gently - but, and this was said with genuine surprise: "I really enjoyed this: it was intelligent!"

And then we were let loose on the champagne and the patisserie. And what patisserie! My novel features a tarte au citron in the first chapter - "The viscous yellow glows against the crisp golden pastry, blind-baked to perfection" - and this later appears malevolent (if a pudding can be malevolent). "The triangles sit quivering in the gloaming. The fluorescent yellow filling wobbling, tantalising her. "Eat me, eat me.""

And so Livre de Poche, with an attention to detail that would befit the best baker, arranged for the patisserie to involve citron mousse and creme pat, perhaps with a mango coulis thrown in. The Paul Sesame (a pun on Paul Cezanne) involved passion fruit gel on a mousse au citron, sesame tuile, black sesame creme pat, citron creme pat and black sesame shortcrust, all topped with a tiny, sesame dusted meringue. I managed one - the citron creme pat rich yet refreshing - and, despite my best efforts, was later defeated by a second.

The next day, we did it again. Not such exquisite patisserie but delicacies made by customers of Mots en Marges (http://www.motsenmarge.com), a bookshop run by Nathalie Iris, who reviews books each week on French breakfast TV. Buoyed by giving a radio interview in French, I spent a couple of hours chatting to around 50 enthusiastic readers, who talked at length about what food, and baking in particular, meant to them.

I had recipe books pressed on me, and delicate canales de Bordeaux - tiny pastries with meltingly-soft custard centres and a caramelised crust - and a speciality walnut, parsley and olive bread made by Nathalie. One customer told me she had spent the day reading my novel and making 100 macarons in seven different flavours - blackberry, citron, pistachio, vanilla, chocolate etc - for a friend's macaron pyramid birthday cake. "You're a good friend," I commented, as I bit into her light-as-air pistachio creation and listened to the tiny coos from other women, doing the same; and she shrugged and said: "It was nothing." As Jenny, one of my characters, says: "Food is love."

With Nathalie Iris at Mots en Marge, her bookshop in La Garenne Colombe.

Perhaps it isn't so surprising, then, that these readers are interested in a novel about baking. For this is a culture that not only appreciates food - and spends far more of it than us Brits - but values the perfectionism and obsessive attention to detail that marks out many a baker - and is prepared to pay a high price for it.

"The bakes in your novels are technical but not creative like those we make in France. Why is that?" the journalist Elsa Menanteau (www.pournouslesfemmes.com) asked. And while part of that may be a failing of my writing, I do believe that our bakes, and by implication our culture, are not as exacting as those of the French. The perfectionism required by these jewel-like patisserie steps up a level here.

Watching these slim, stylish women, who view gateau as a treat to be indulged in occasionally, I hoped they would be kind to the vastly-inferior bakers in The Art of Baking Blind. And perhaps they will. For the reviewers understood that this is a novel about being a woman as much as about baking. As a glorious review in French Elle puts it: "The novel, more subtle than one might imagine, effectively pinpoints the diktats that society imposes on women: motherhood sold as the panacea or the tyranny of slimness. Devour at once."

As I bought my profiteroles, before catching the Eurostar back home, I told the young shop assistant I'd just written a novel about why we bake. (I am shameless about it now and hustle everywhere.)

She raised a perfectly-arched eyebrow, this woman who had just sold over 20 euros of choux pastry to the previous customer, and I could swear she rolled her eyes.

"Now that," she said. "Is a very good question."