Lindsay Townsend's Blog, page 25

May 8, 2011

Sample Sunday - 'To Touch The Knight'

Here's a sample of my forthcoming historical romance, To Touch The Knight, due out in July. This is the very start of the novel.

Prologue - Summer 1349

Warren Hemlet, England.

"He has walled us in alive! Our own lord has abandoned us!"

"He cannot do this!"

But he has done so, Edith thought, as she crouched to give her shivering cow a drink from a bucket of water. Sir Giles de Rothencey, their brutal lord of Warren Hemlet, had driven all of them, villagers and beasts alike, into the church and had ordered his men to seal them within to die.

He might have spared her, for she was the smith's widow, skilled in metal-working and so useful, but she had entered the simple, windowless church willingly enough. It could be that they would all die of the pestilence soon, and she wanted to be with her own people.

"We have wine and water," she reminded the others, rising to her feet and speaking above the hammering as their lord's men barred and sealed the door. "We are in a holy place." She hoped her voice would not waver as she said this - she had fallen out with God. "We are together."

"What use is that when our lord herds us in here, the hale and the sickening, so all perish?"

Edith trod on the loud-mouth's foot.

"We are together," she repeated. "Those men outside will not stay for long. If we go quiet and stay quiet, they will think us dead. We know this has happened before, in other places."

Around her the villagers grew silent, thinking perhaps, as she was, of the ghastly rumors concerning the pestilence. Only last month a peddler had come to Warren Hemlet with gruesome stories of people going to bed healthy and dying in the night; of people dying in the fields, in the washing houses, in the streets. No one was safe, or spared. She had seen it herself, all this last week, in her own village. So many had died. From their village of four-score souls, only three and twenty were left. Of these, Anwyl was already coughing in one corner and Peter the shepherd lay shuddering and whimpering amidst his scrawny sheep, his neck covered with red boils.

And then their lord had come - not to save them, but to ensure the sickness did not spread to him. Which was how they came to be here, in the church: a stone building Sir Giles intended would be their tomb.

"But we shall escape," she said aloud. If she was to die, she wanted to do so out of doors, under the blue sky and trees. "We shall break out."

"And flee this place, that God and his saints have left," said her brother quietly. Gregory could always speak and be heard: he was the priest here, so people listened.

"How do we do that when we are locked in?" demanded the loud-mouth.

Edith threaded her way round the villagers to the stone font and picked up the baby she had carried into the church with her and laid in the dry stone bath. She unwrapped the "baby's" saddling bands to reveal her own metal-working tools, bundled together in a rough blanket.

"We shall get out," she said.

If you enjoy this excerpt, please comment or re-tweet it.

Prologue - Summer 1349

Warren Hemlet, England.

"He has walled us in alive! Our own lord has abandoned us!"

"He cannot do this!"

But he has done so, Edith thought, as she crouched to give her shivering cow a drink from a bucket of water. Sir Giles de Rothencey, their brutal lord of Warren Hemlet, had driven all of them, villagers and beasts alike, into the church and had ordered his men to seal them within to die.

He might have spared her, for she was the smith's widow, skilled in metal-working and so useful, but she had entered the simple, windowless church willingly enough. It could be that they would all die of the pestilence soon, and she wanted to be with her own people.

"We have wine and water," she reminded the others, rising to her feet and speaking above the hammering as their lord's men barred and sealed the door. "We are in a holy place." She hoped her voice would not waver as she said this - she had fallen out with God. "We are together."

"What use is that when our lord herds us in here, the hale and the sickening, so all perish?"

Edith trod on the loud-mouth's foot.

"We are together," she repeated. "Those men outside will not stay for long. If we go quiet and stay quiet, they will think us dead. We know this has happened before, in other places."

Around her the villagers grew silent, thinking perhaps, as she was, of the ghastly rumors concerning the pestilence. Only last month a peddler had come to Warren Hemlet with gruesome stories of people going to bed healthy and dying in the night; of people dying in the fields, in the washing houses, in the streets. No one was safe, or spared. She had seen it herself, all this last week, in her own village. So many had died. From their village of four-score souls, only three and twenty were left. Of these, Anwyl was already coughing in one corner and Peter the shepherd lay shuddering and whimpering amidst his scrawny sheep, his neck covered with red boils.

And then their lord had come - not to save them, but to ensure the sickness did not spread to him. Which was how they came to be here, in the church: a stone building Sir Giles intended would be their tomb.

"But we shall escape," she said aloud. If she was to die, she wanted to do so out of doors, under the blue sky and trees. "We shall break out."

"And flee this place, that God and his saints have left," said her brother quietly. Gregory could always speak and be heard: he was the priest here, so people listened.

"How do we do that when we are locked in?" demanded the loud-mouth.

Edith threaded her way round the villagers to the stone font and picked up the baby she had carried into the church with her and laid in the dry stone bath. She unwrapped the "baby's" saddling bands to reveal her own metal-working tools, bundled together in a rough blanket.

"We shall get out," she said.

If you enjoy this excerpt, please comment or re-tweet it.

Published on May 08, 2011 00:00

Sunday Sample - To Touch The Knight

Here's a sample of my forthcoming historical romance, To Touch The Knight, due out in July. This is the very start of the novel.

Prologue - Summer 1349

Warren Hemlet, England.

"He has walled us in alive! Our own lord has abandoned us!"

"He cannot do this!"

But he has done so, Edith thought, as she crouched to give her shivering cow a drink from a bucket of water. Sir Giles de Rothencey, their brutal lord of Warren Hemlet, had driven all of them, villagers and beasts alike, into the church and had ordered his men to seal them within to die.

He might have spared her, for she was the smith's widow, skilled in metal-working and so useful, but she had entered the simple, windowless church willingly enough. It could be that they would all die of the pestilence soon, and she wanted to be with her own people.

"We have wine and water," she reminded the others, rising to her feet and speaking above the hammering as their lord's men barred and sealed the door. "We are in a holy place." She hoped her voice would not waver as she said this - she had fallen out with God. "We are together."

"What use is that when our lord herds us in here, the hale and the sickening, so all perish?"

Edith trod on the loud-mouth's foot.

"We are together," she repeated. "Those men outside will not stay for long. If we go quiet and stay quiet, they will think us dead. We know this has happened before, in other places."

Around her the villagers grew silent, thinking perhaps, as she was, of the ghastly rumors concerning the pestilence. Only last month a peddler had come to Warren Hemlet with gruesome stories of people going to bed healthy and dying in the night; of people dying in the fields, in the washing houses, in the streets. No one was safe, or spared. She had seen it herself, all this last week, in her own village. So many had died. From their village of four-score souls, only three and twenty were left. Of these, Anwyl was already coughing in one corner and Peter the shepherd lay shuddering and whimpering amidst his scrawny sheep, his neck covered with red boils.

And then their lord had come - not to save them, but to ensure the sickness did not spread to him. Which was how they came to be here, in the church: a stone building Sir Giles intended would be their tomb.

"But we shall escape," she said aloud. If she was to die, she wanted to do so out of doors, under the blue sky and trees. "We shall break out."

"And flee this place, that God and his saints have left," said her brother quietly. Gregory could always speak and be heard: he was the priest here, so people listened.

"How do we do that when we are locked in?" demanded the loud-mouth.

Edith threaded her way round the villagers to the stone font and picked up the baby she had carried into the church with her and laid in the dry stone bath. She unwrapped the "baby's" saddling bands to reveal her own metal-working tools, bundled together in a rough blanket.

"We shall get out," she said.

If you enjoy this excerpt, please comment or re-tweet it.

Prologue - Summer 1349

Warren Hemlet, England.

"He has walled us in alive! Our own lord has abandoned us!"

"He cannot do this!"

But he has done so, Edith thought, as she crouched to give her shivering cow a drink from a bucket of water. Sir Giles de Rothencey, their brutal lord of Warren Hemlet, had driven all of them, villagers and beasts alike, into the church and had ordered his men to seal them within to die.

He might have spared her, for she was the smith's widow, skilled in metal-working and so useful, but she had entered the simple, windowless church willingly enough. It could be that they would all die of the pestilence soon, and she wanted to be with her own people.

"We have wine and water," she reminded the others, rising to her feet and speaking above the hammering as their lord's men barred and sealed the door. "We are in a holy place." She hoped her voice would not waver as she said this - she had fallen out with God. "We are together."

"What use is that when our lord herds us in here, the hale and the sickening, so all perish?"

Edith trod on the loud-mouth's foot.

"We are together," she repeated. "Those men outside will not stay for long. If we go quiet and stay quiet, they will think us dead. We know this has happened before, in other places."

Around her the villagers grew silent, thinking perhaps, as she was, of the ghastly rumors concerning the pestilence. Only last month a peddler had come to Warren Hemlet with gruesome stories of people going to bed healthy and dying in the night; of people dying in the fields, in the washing houses, in the streets. No one was safe, or spared. She had seen it herself, all this last week, in her own village. So many had died. From their village of four-score souls, only three and twenty were left. Of these, Anwyl was already coughing in one corner and Peter the shepherd lay shuddering and whimpering amidst his scrawny sheep, his neck covered with red boils.

And then their lord had come - not to save them, but to ensure the sickness did not spread to him. Which was how they came to be here, in the church: a stone building Sir Giles intended would be their tomb.

"But we shall escape," she said aloud. If she was to die, she wanted to do so out of doors, under the blue sky and trees. "We shall break out."

"And flee this place, that God and his saints have left," said her brother quietly. Gregory could always speak and be heard: he was the priest here, so people listened.

"How do we do that when we are locked in?" demanded the loud-mouth.

Edith threaded her way round the villagers to the stone font and picked up the baby she had carried into the church with her and laid in the dry stone bath. She unwrapped the "baby's" saddling bands to reveal her own metal-working tools, bundled together in a rough blanket.

"We shall get out," she said.

If you enjoy this excerpt, please comment or re-tweet it.

Published on May 08, 2011 00:00

May 4, 2011

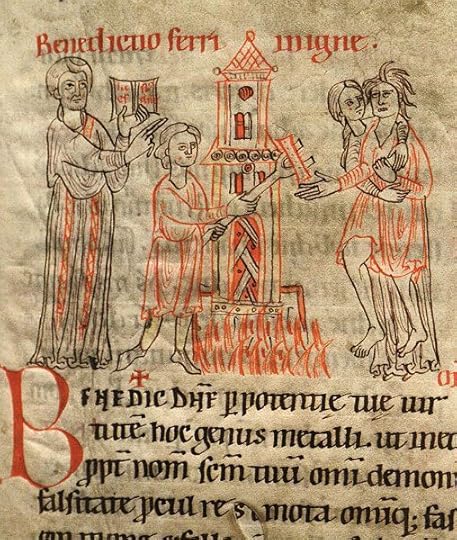

Medieval truth or dare: trial by ordeal

Murders and other crimes happened in the Middle Ages but there was no formal police force and no forensics, no great interest in clues. So how did medieval people decide whether someone was guilty or innocent?

Murders and other crimes happened in the Middle Ages but there was no formal police force and no forensics, no great interest in clues. So how did medieval people decide whether someone was guilty or innocent? What mattered was what the community in which the crime took place thought. If you could produce witnesses you could vouch for your good character, and from Anglo-Saxon times status counted, so a thegn's evidence - like his life - was legally worth more than a churl's. Those accused of a crime who were unwilling to pay the standard fine could also hope to clear their names by swearing oaths to God - this was popular in the early Middle Ages and called 'compurgation': a person accused of a crime swore on oath that he or she was innocent and often had a number of associates swear the oath with him to 'prove' guilt or innocence. This system was understandably open to abuse, so by the ninth century the church actively backed another way to reveal God's judgment in any crime - by means of the ordeal.

An ordeal was precisely that - a trial the accused could undergo to submit to the divine and so prove they were not guilty. The term ordeal has the meaning of "judgment, verdict" in old English and in the Middle Ages many believed they were genuinely submitting to the judgment of God.

In the ordeal of boiling water, a man would plunge his hand or arm into a cauldron of boiling water, after which the hand would be bound up, sealed with the seals of the church and then left. After three days the bandages would be removed and if the man showed signs of scalding he would be pronounced guilty.

There was also an ordeal by fire, where a person had to carry a red hot iron (weighing one pound in the late tenth century, or three pounds for the 'threefold ordeal') for a certain distance. Again the suspect's hand was bound up and later examined to pronounce innocence or guilt. There were ordeals of cold water, similar to the later practice of ducking a witch. In the Assize of Clarendon in 1166, the law of England stated: "anyone, who shall be found, on the oath of the aforesaid [a jury], to be accused or notoriously suspect of having been a robber or murderer or thief, or a receiver of them ... be taken and put to the ordeal of water."

There was also an ordeal by fire, where a person had to carry a red hot iron (weighing one pound in the late tenth century, or three pounds for the 'threefold ordeal') for a certain distance. Again the suspect's hand was bound up and later examined to pronounce innocence or guilt. There were ordeals of cold water, similar to the later practice of ducking a witch. In the Assize of Clarendon in 1166, the law of England stated: "anyone, who shall be found, on the oath of the aforesaid [a jury], to be accused or notoriously suspect of having been a robber or murderer or thief, or a receiver of them ... be taken and put to the ordeal of water."There was also ordeal by combat, also known as 'trial by battle', a way of 'proving' guilt or innocence that was much favoured throughout the Middle Ages. Introduced into England by the Normans, the earliest case in which trail by battle is recorded was Wulfstan v. Walter (1077), eleven years after the Conquest, possibly between a Saxon and a Norman. By the 12th century it was the way nobles would often settle disputes. The parties fought on a duelling ground and swore before they began that they had not used witchcraft to help them.

Women were usually banned from taking part in such trials but not always, a detail I exploit in my novel, A Knight's Captive. In parts of Germany a woman might fight a man in a trial of battle if the man had one hand tied behind his back. Lepers were banned from fighting in ordeals but hired champions could sometimes be used - these were usually desperate men, since they could be killed in the ordeal of battle, or afterwards hanged or lose a hand or foot if they were judged to have lost. In medieval France the professional champion was seen in the same way as a prostitute.

Of all the ordeals, trial by battle remained in force the longest - it was not abolished in England until as late as 1819.

Published on May 04, 2011 01:35

April 30, 2011

Interview at 'The Roses of Prose'

I'm in the Saturday Spotlight at The Roses of Prose today, chatting about To Touch the Knight and other stuff. There's a giveaway, too, so why not pop over right away!

I'm in the Saturday Spotlight at The Roses of Prose today, chatting about To Touch the Knight and other stuff. There's a giveaway, too, so why not pop over right away!

Published on April 30, 2011 08:11

April 15, 2011

'A Rose of Midsummer' and other stories

I've put five of my previously published short stories up on Smashwords as a collection today, so now they're available for download onto your ereader. They're light, romantic and here are the details.

I've put five of my previously published short stories up on Smashwords as a collection today, so now they're available for download onto your ereader. They're light, romantic and here are the details.

Published on April 15, 2011 01:51

Free read: 'A Rose of Midsummer' and other stories

I've put five of my previously published short stories up on Smashwords as a collection today, so now they're available for download onto your ereader. They're light, romantic and free, and here's the link:

I've put five of my previously published short stories up on Smashwords as a collection today, so now they're available for download onto your ereader. They're light, romantic and free, and here's the link:http://www.smashwords.com/books/view/53650

Published on April 15, 2011 01:51

April 13, 2011

Devon in the spring again

Around this time every year I try to get down to my inlaws in sunny Devon, and I made it last weekend. A very brief trip, too brief considering the six-hour drive each way and much too brief considering the hospitality. We did go for a companionable walk, since they're indefatigable ramblers and cyclers, and although the camera batteries ran out too early I still have one pic to show you.

Around this time every year I try to get down to my inlaws in sunny Devon, and I made it last weekend. A very brief trip, too brief considering the six-hour drive each way and much too brief considering the hospitality. We did go for a companionable walk, since they're indefatigable ramblers and cyclers, and although the camera batteries ran out too early I still have one pic to show you. The flower in the second picture is azalea precox and is always out very early, with the daffodils. Mostly it's at its best on my birthday in February, so I have a soft spot for it. I found it on the camera, so here it is - better late than never!

The flower in the second picture is azalea precox and is always out very early, with the daffodils. Mostly it's at its best on my birthday in February, so I have a soft spot for it. I found it on the camera, so here it is - better late than never!

Published on April 13, 2011 11:35

April 6, 2011

Phew! The streets of London, 14th-century style.

Last night I watched a BBC2 programme about medieval London and its sanitation problems. Dan Snow's vivid and interactive account - there was a small scratch-card, supplied by the Radio Times, which I sniffed at the right moment - told me much I already knew but it was overwhelming seeing and smelling it all at once. By the 14th century, London was a city of over 100,000, a teeming, dark, filthy smelling and sewerage-filled place. I was fascinated by the platform shoes medieval Londoners wore to try to wade through the sloppy streets and also by the work of the gong farmers - cleaners armed with rakes and shovels, working at night, trying to clean the streets.

Last night I watched a BBC2 programme about medieval London and its sanitation problems. Dan Snow's vivid and interactive account - there was a small scratch-card, supplied by the Radio Times, which I sniffed at the right moment - told me much I already knew but it was overwhelming seeing and smelling it all at once. By the 14th century, London was a city of over 100,000, a teeming, dark, filthy smelling and sewerage-filled place. I was fascinated by the platform shoes medieval Londoners wore to try to wade through the sloppy streets and also by the work of the gong farmers - cleaners armed with rakes and shovels, working at night, trying to clean the streets.This was a gruesome account at times, especially when Dan spoke of the medieval butchers and tanners, and then the horrors of the Black Death, which raged in London for two years (1348-50) but I shall be watching again next week, when the series recreates the stench of pre-revolution Paris.

Published on April 06, 2011 10:39

April 3, 2011

The last of the Anglo-Normans: The loss of the White Ship

On November 25th, 1120, The White Ship was wrecked in a storm and sank in the English Channel. This terrible accident claimed over 300 lives and turned the course of English medieval history, since one of the victims was William 'the Atheling', seventeen years old and the only legitimate son of King Henry I of England and his queen Matilda, who had died two years before.

The White Ship was a modern vessel, a sturdy cog owned by Thomas FitzStephen, who was also on board, but the channel crossing from Normandy to England is treacherous, especially in winter. Henry's ship had already left Barfleur, on the north-western coast of France, in daylight, but when Fitzstephen's ship eventually sailed, after being loaded with more casks of wine, it was night. Worse, everyone on the ship was drunk. The ship struck a rock off Barfleur off the coast of north-western France and was wrecked. Only a butcher called Berthold from Rouen, on board to chase up payment, survived because the ramskins he was wearing saved him from exposure. Prince William and many of his friends, all young nobles, were drowned. Chroniclers of the time said that Thomas FitzStephen, knowing that Prince William was lost, allowed himself to drown rather than face King Henry.

At court, none of the barons dare tell the king. A child was finally sent with the terrible news. Henry fainted and afterwards was said never to smile again.

Henry, stricken with grief, also afraid for his crown. His other legitimate child, named Matilda like her mother, was a daughter and in the Middle Ages women were not thought capable of ruling without male help. The traditional role of a queen was as a help-meet of the king and an intermediary for petitioners seeking mercy from the king. She was not expected to rule alone. Aware of this, King Henry married again within 3 months of the sinking of the White Ship and the loss of his male heir, but had no further legitimate children.

Henry was terrified of the prospect of no obvious male succession to the English crown, won by his father William of Normandy at the battle of 1066 - the more so perhaps because he owed his own title of king to an 'accident' in the New Forest in August 1100 when his older brother, William Rufus, the King of England, was killed by an arrow while out hunting. Accident or assassination? It is still unclear but the younger brother, landless Henry, wasted no time in seizing the royal treasury and securing his position.

The death of William Rufus had favored him but the sinking of The White Ship threw his dynastic aims into turmoil. He attempted to extract promises of loyalty from his barons to his daughter Matilda, but some of the barons favored Henry's favorite nephew Stephen and when King Henry died in 1135, Stephen was crowned king of England in his place.

Matilda and her supporters saw this as a betrayal and both factions fought for their claims over England for over 20 years, a conflict which forms the backdrop for my novel A Knight's Vow, set in 1138.

Had William not been traveling on The White Ship all those years ago in 1120, if he had lived and succeeded his father, England would have seen a different line of Kings - Anglo-Normans instead of the later Angevins. No Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, no Richard the Lionheart, no King John - all descended from Matilda's marriage to Geoffrey of Anjou.

Published on April 03, 2011 13:21

March 10, 2011

'Night of the Storm' is now an ebook

My 1996 Hodder title, Night of the Storm, has been out of print for a while, but no longer. I've uploaded it to Smashwords and it's yours for $2.99 in all the usual formats. Here's the link.

My 1996 Hodder title, Night of the Storm, has been out of print for a while, but no longer. I've uploaded it to Smashwords and it's yours for $2.99 in all the usual formats. Here's the link. Readers of A Secret Treasure will recognise the Rhodes setting, though this is a full-length book blending suspense, romance and the wildlife smuggling trade.

Published on March 10, 2011 22:18