Avi's Blog, page 10

January 2, 2024

How the Past Comes into the Present

Hilary Mantel, the late British author who wrote such outstanding historical fiction as the Wolf Hall trilogy, is quoted as saying, “History is not the past, it’s the method we have evolved of organizing our ignorance of the past.”

That’s also an apt definition for historical fiction, as it is the academic discipline of history itself. The difference; the historian, at least we like to assume, is trained to search out the facts, data, and other evidence to present a meaningful — and objective — narrative of past events.

The writer of historical fiction, while trying to hew to selective facts, invents a personalized accounting for what happened. It suggests real history even though it isn’t. It’s also subjective in its point of view.

Historical fiction — which, in English, seems to have begun with Sir Walter Scott’s Waverly published in 1814 — takes many forms. Its authors follow facts in varying degrees. Thus, my The Button War is based on a brief story my late father-in-law told me about his experience in World War One when he was a boy. Otherwise, it is utterly fiction.

Gold Rush Girl, set in 1848 San Francisco, is as close a factual rendering of Gold Rush San Francisco as I could create, based on my research. Early in the book, the girl protagonist attends a dance class on the East Coast. I tracked down a mid-19th-century etiquette book that had rules for such events. You may be sure I used it. That said, the story in Gold Rush Girl is entirely invented.

In my recent Loyalty, a tale of the early days of the American Revolution, I could take advantage of the many accounts of the battles of Lexington and Concord. But in my telling, I inserted a fictional character who reacts to the battles in a very personal way: he is a witness not just to the battles, but to the death of his brother-in-law.

The story I tell is fiction, but, besides the details of the battle — which I believe are true — I have my protagonist — witness that death. Fiction. But I gave that brother-in-law the real name of a young man who actually died in those battles.

Fact and fiction combined.

Sometimes I am corrected. In The Secret School, set in 1925, fourteen-year-old Ida drives to school in a Model T Ford. (Colorado introduced driving licenses in 1936.) She handles the steering wheel. Being very short, her younger brother Felix, on the car floor, works the brake and clutch pedals. Those peddles, as I researched them, were many and complicated to use. In my telling I got the pedals mixed up. Shortly after publication, I received a letter setting me to rights. Later editions have those pedals right.

Now, in 2024 I will be publishing (working title) Lost in the Empire City. Set in New York City in 1911, it tells the tale of an immigrant Italian boy who must navigate the most crowded city in the world — on his own.

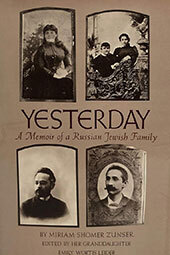

There are countless accounts of immigrants passing through Ellis Island. They are fascinating, and often moving. As it happens, one of the accounts I read was by my grandmother, Miriam Shomer Zunser.

Her memoir, titled Yesterday, was first published in 1939, then edited by my twin sister, Emily Leider, and reissued by HarperCollins in 1978. It recounts among many other things, how, as a girl, my grandmother came to America from Ukraine in 1889.

In the book, my Grandmother recounts how, when she arrived in America, she was given a banana by her father. Never having seen a banana before she was greatly puzzled as to how to eat it.

That factual incident is in my fictional book.

A 19th-century fact, written down by my grandmother in 1939, edited by my twin sister in 1978, written into my fiction in 2024.

My way of organizing the past into a contemporary fictional narrative.

December 26, 2023

The Red Fox

It is the holiday season again. This time it’s a period of chaos, violence, and confusion. But sometimes, living in a forest as I do, I get a glimpse of nature in all its living beauty, its calming beauty.

So, it was this gray (9 am) morning, cloudy, with light snow falling — on yesterday’s snow — when I descended from our second floor to the first. At the bottom of the steps is a heavy door, set with double glass, which opens onto a side porch and beyond. As I reached the main floor I looked out. Sitting there, staring into our house, was a red fox.

I stared back.

She/he (?) was with winter coat, a deep rusty red, dark paws, a white chest, and a thick, big bushy gray tail. Perky ears. Long red snout, white fringed, black nose leather. A very beautiful creature. Inscrutable expression.

The two of us just looked at one another.

(I can’t show you because I’m not one of those people who carries a camera in my hip pocket 24/7. I prefer to look and shape a memory.)

I knew what I was seeing. What did the fox see?

When the fox moved away, I went out because I had a chore to which I needed to attend. The fox was gone.

But as I was coming back from attending to my task — walking along the driveway — the fox reappeared, saw me, and stopped, perhaps fifteen feet away. Once again we looked at one another. Had it come back to give me a message?

“Good morning, fox,” I said in an even voice. “Nice to see you. Off to work? Hunting for food? Merry Christmas!”

The fox — who must have heard me — came slowly forward, stopped — ten feet away — then turned, and made a wide circle around me, its light weight allowing her to walk atop the snow. No panic. No alarm, just a slow trot with an occasional glance at me, before disappearing over a hill.

I came back inside and sat down at my desk. That fox and I both had work to do.

But I felt privileged to have shared a moment of calm nature in all its beauty. For a moment the world’s chaos retreated.

Lucky me.

May you all find such moments this coming year.

December 19, 2023

The Pleasure of Re-Reading

I’m sure I’m preaching to the choir here when I speak of the pleasures of reading. But perhaps not enough is said about the pleasure of re-reading.

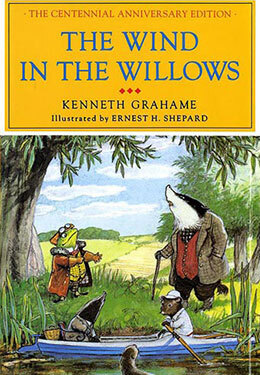

I think there have been four works of fiction that have most influenced my writing life: Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Graham, [its graceful, evocative, and often hilarious writing], Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, [its wonderful characters, and that extraordinary first chapter] The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett, [the explosive energy of its prose style] and Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, [the breathless romance of historical adventure bolstered by a brilliant cast of characters).

(I suspect that if any of you have read more than a few of my books, you will note the influence.)

It’s worth noting that I read all of these four books before I reached my twentieth birthday. Now, in my eighties, I still find them wonderful. Indeed, from time to time, I re-read them, in whole or in part. I do so for continual enjoyment, but also to remind myself what great writing is all about, the kind of writing I have always—and still—aspire to. These books—and the writers—are my constant teachers.

As a reader who is almost always swept away by the plot, re-reading allows for a more leisurely stroll through the text, allowing me to note writing nuances I previously missed, a greater appreciation for character delineation, plus the sheer pleasure of taking note of writing skills I took for granted. I also note aspects of plot details I have inevitably passed over. Moreover, I think re-reading always provides a greater understanding of a great writer’s depth and perception of life. Such writing deepens my experience and my understanding of the world. And when, as is sometimes the case, the re-reading takes place after years, I am reading the book as a different person. I think you can measure your growth by how you take to a re-reading.

As a young writer, I was much attracted by Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises. A recent re-reading found me disliking the book a great deal. I found the stylistic mannerisms annoying, and the characters downright unlikeable.

A comparable re-reading of Austin’s Pride and Prejudice made me much more aware of her sharp satire and delicious humor than I could grasp when younger.

[All this said I have an almost visceral dislike of re-reading my books. I too often find myself confronted and confounded by the bits and pieces I could have, should have made better.]

It’s commonplace to sometimes think, I wish I could have lived a past time again. Perhaps the closest way of achieving that is by re-reading a book that was once dear to you.

I’ll say the obvious: we all grow older. By way of contrast, great books don’t become older, just wiser.

December 12, 2023

How Publishing Used to Feel

Among Friends is “a history of an industry transformed by consolidation and shifting tastes.” Recently published, since it costs two hundred dollars, I’m not likely to read this fascinating history of the recent publishing industry.

Among Friends is “a history of an industry transformed by consolidation and shifting tastes.” Recently published, since it costs two hundred dollars, I’m not likely to read this fascinating history of the recent publishing industry.

That said, I have been part of the industry since 1968, when my first book, Things That Sometimes Happen, was accepted for publication. Before actual publication, that book had four editors because the editors kept switching their employment from one publisher to another. That was possible because there were so many editorial jobs available, and the industry was booming.

(In revised—and much better form—that book is still in print.)

Furthermore, TTSH was a picture book but, before the work on the book was completed, the illustrator floated into Mexico for some kind of hallucinogenic experience. The art director (whoever that was) finished the art.

Then by some kind of “mistake” or so I was told, the book was soon pulled from publication.

A different time, indeed.

Such was my introduction to the world of the professional writer. I have no desire to go back to that experience.

Since then, over the years I had much better experiences and developed fond and close friendships (as well as good, lasting books) with several editors such as Fabio Cohen, Dick Jackson, and Elise Howard. I had productive relationships (and many friendships) within publishing houses, in particular Pantheon Books, Hyperion, Simon & Schuster, and HarperCollins.

I not only knew many of the people involved, from marketing to copyediting folk, but these working relationships were also friendships. Among Friends is a good summary of how publishing used to feel.

Much of that has indeed changed. There are now only four major publishers. The reading public has diminished. Whereas bookstores were vital to the industry, Amazon is the principal source of bookselling. Marketing has radically shifted to social media. The last book tour that had been organized for me was canceled because of COVID-19. The many school visits—where and when I interacted with my readers—have shifted to virtual visits, not so engaging for me. It was not only my readers I met, but teachers and librarians. I don’t just miss them, but all those people helped shape my work. Finally, the time it takes to publish a book has lengthened, with the creative interaction between editor and writer not as effervescent and fun.

And yet, and yet….

My writing of books goes on. The desire for quality and the struggle for that quality has not changed and sometimes is achieved. I have published many books, and more (hopefully) will come.

So, it’s not really my right to complain. Instead, I must adjust to the changes.

In Among Friends there is the story that John Le Carre, whenever he got a good publishing deal said, “Baby will eat tonight.” My kids feed themselves, but I might just as well say to my wife, “Good news! The mortgage will be paid tonight.”

That part has not changed.

December 5, 2023

Inarticulate

photo credit: Sasun1990 | 123rf.com

photo credit: Sasun1990 | 123rf.com As I was working today on a book, a message suddenly popped up on my screen:

“Did you know that you used more unique words than 85% of Grammarly users?”

First, I was startled by the apparent fact that Grammarly was tracking my words. Secondly, I wondered why they were tracking my work. Thirdly, while I am aware that I have a large vocabulary, and that I try to make my writing varied, I make it a point — considering my young readers — NOT to use obscure or excessively complex language. In fact, I am a believer in simple, straightforward writing to express the emotions about which I am writing.

On the same day, I read an article in the New York Times, “An Ancient Solution to Our Current Crisis of Disconnection.”

The article, by Mr. John Bowe, had this to say:

“Hannah Hobson, a lecturer in psychology at the University of York [UK] who has studied the connections among language, communication, and mental health … has found repeatedly that the inability to express feelings or ask for help can often correlate with existing or developing mental health issues among youth. Conversely … improved communication skills correlate with youngsters’ emotional development and well-being.”

Mr. Bowe is proposing the teaching of the (now) ancient teaching of rhetoric, which in its simplest form is the art of speaking and listening. When you consider the brevity of e‑mail, the general decline in reading, and that social media communication is as slight in form as it is in content, it is hardly a wonder that young people have not been taught how to communicate their complex feelings and emotions.

One often hears the general sense that young people, in particular adolescents, are very emotional. True enough. And yet, in our current society, their experience with how to express those emotions is at best limited, cut off, and truncated. That inability to communicate apparently can lead to mental issues.

A good number of years ago I was asked to speak at a boy’s juvenile detention center in Virginia. Slumped in their chairs, their body language telling me that they were forced to be there, the young men were polite, but clearly not particularly interested in what I had to say or me for that matter. That is, not until it came out that Walter Dean Myers was a good friend of mine. Then they literarily sat up in the chairs and began to pepper me with questions about him. It appeared that many of these young prisoners had read Monster, and the book had articulated their feelings, so that I, by virtue of my connection with Walter, was suddenly given a flood of words and ideas. It was startling and powerful evidence of what a book can mean to young people.

I don’t want to suggest that reading is a cure for all the problems of mental illness in our country. But I will say if people cannot be taught or experience how to express their feelings, frustrations, and conflicts with words, they will find ways—destructive ways—to express their emotions.

Social media is often (rightly, I think) criticized for its misinformation, lack of real content, and simplistic articulation, but perhaps its most profound problem is that it is an inept way to communicate.

So, when I am told (by Grammarly) that my writing is full of unique words, Grammarly is not so much praising me, as revealing that a large part of the population is inarticulate.

The moral: be worried about the person who cannot speak or write their thoughts.

November 28, 2023

Of Passing Interest

Here’s a mordant question. What happens to a writer’s work when she/he passes on? The question comes up because of an article, “The Business of Mining Literary Estates is Booming,” which appeared in the November 11, 2023, The Economist. (Digital access to this article is limited, but your public library will have the print edition.)

Have you wondered about the many Sherlock Holmes stories that have appeared of late? It’s because, generally speaking, an author’s work is owned by his/her estate seventy years after death. After that period of time, anyone is free to use the characters and even the stories as they will. So, right now, you are free to write your own Sherlock Holmes story. Or Wind in the Willows story. Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Little Women or Oz stories.

Have you wondered about the many Sherlock Holmes stories that have appeared of late? It’s because, generally speaking, an author’s work is owned by his/her estate seventy years after death. After that period of time, anyone is free to use the characters and even the stories as they will. So, right now, you are free to write your own Sherlock Holmes story. Or Wind in the Willows story. Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Little Women or Oz stories.

Like many couples, my wife and I have wills in which the spouse inherits the other’s assets. Writing Copyrights are considered assets. Furthermore, there is an agreement that my agent will continue to function to represent me after my demise. when both my wife and I pass on, the assets—which is to say the rights to my books—will still be under someone’s control. That means if anyone wishes to make a movie—or a game—out of one of my books there is a legal framework to do that. For X number of years, depending on when the book was published.

Indeed, The Economist’s article points out that Roald Dahl’s estate recently sold the rights to his books to Netflix for 700 million dollars. No wonder that a new business organization, International Literary Properties has come into being to buy literary estates. They seem to have purchased some fifty of these estates, including such diverse works as that of Langston Hughes and Georges Simenon.

Indeed, The Economist’s article points out that Roald Dahl’s estate recently sold the rights to his books to Netflix for 700 million dollars. No wonder that a new business organization, International Literary Properties has come into being to buy literary estates. They seem to have purchased some fifty of these estates, including such diverse works as that of Langston Hughes and Georges Simenon.

Then there is the Society of Authors — a “United Kingdom trade union for professional writers, illustrators and literary+ translators, founded in 1884 to protect the rights and further the interests of authors.” It also acts as trustee for more than fifty authors’ estates.

Of course, there is also the question of how to use these rights. Does one alter the texts to bring them into line with modern sensibilities, as well as political and social considerations?

The driving force behind all this appears to be TV and audiobook rights, and the quest for content. That said, I can say from personal experience, that the selling of such rights is complex, torturous and, generally speaking, does not come to any light. In my case, it is further complicated by the fact that “digital rights,” and the like, now part of all publishing contracts, did not even exist when my first book was published in 1970.

The driving force behind all this appears to be TV and audiobook rights, and the quest for content. That said, I can say from personal experience, that the selling of such rights is complex, torturous and, generally speaking, does not come to any light. In my case, it is further complicated by the fact that “digital rights,” and the like, now part of all publishing contracts, did not even exist when my first book was published in 1970.

My response to all of this is: why not read the books in their original form? I can guarantee they will be better, more engaging, and more meaningful than any film variant.

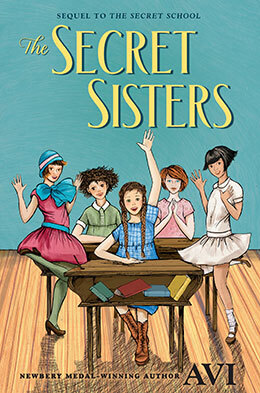

On the other hand, if you want to use my recently published The Secret Sisters, you are free to do so after 2093.

I probably won’t complain.

November 21, 2023

What should the page of a manuscript look like?

You may not know it but there is such a thing as the “Golden Ratio,” which suggests the best way to create a written page layout. This Golden Ratio comes to us from very ancient Greek geometry and mathematics, in particular the work of the philosopher and mathematician, Pythagoras, born about 570 BCE. But the first known reference to the term comes hundreds of years later from Euclid. These are names you may recall from your high school Geometry class. You might think they have nothing to do with modern book publishing, but they do.

The standard definition of this “Golden Ratio” is achieved when you set page margins of 2.23″ on all four sides of 8.5″ × 11″ paper. That seems to be close to the golden ratio.

I got to thinking about this because I was printing out a new manuscript, preparatory to reading and editing it. While I do compose my work on a computer, and thereby endlessly read and reread the text on a screen, I find I need to go to a text printed on paper to do my fine editing.

When I do that, I am always—rather mindlessly—setting up the margins. This time—for no particular reason—I thought about that “Golden Ratio.”

Does it matter?

A digression. Years ago, a good friend asked me to read a manuscript someone they knew had written.

Out of friendship with that person, I agreed.

When I pulled the manuscript out of its envelope I found (this was before the common use of computers) it was about a hundred and fifty pages long, single-space typed, with page margins at about half an inch on top, bottom, sides.

I think I audibly gasped. It was all but a solid block of words—as far from the Golden Ratio as one could get.

It was, to my eyes, unreadable.

I returned it to the author and suggested it be, at least, reformatted in Golden Ratio format.

I never saw it again.

Granted, an extreme case. But I do know that when I randomly meander through a bookstore (or a library) the way a book is published influences what I choose to read.

So it is, over the years I have experimented with page format. I have (with a computer) shaped my text so it has the dimensions of a paper book text. I have laid it out with double columns. As I have discussed elsewhere here, I have used different fonts. What I am trying to do is read my own work in a different way, so that I am reading it, not just slipping, and sliding over a very familiar text.

But guess what? I inevitably create a printed text close to the Golden Ratio.

It truly is much easier to read.

Do I understand why? No. Nor have I explored the reasons as to why it works. I just know a text set forth in the “Golden Ratio,” is easier, and more pleasant to read.

Good enough for the ancient Greeks. Good enough for me.

November 14, 2023

Waiting

There are many skills that professional writers have to master. I’m sure we could all think of many at the click of a computer key. Among the many are Language, Imagination, Perseverance, Work habits, Knowledge of Vocabulary, and Grammar. It’s easy to go on, and I am sure you can think of many others to add to this list. But one of the skills a writer must master is one that I don’t think is often mentioned: waiting.

There are many skills that professional writers have to master. I’m sure we could all think of many at the click of a computer key. Among the many are Language, Imagination, Perseverance, Work habits, Knowledge of Vocabulary, and Grammar. It’s easy to go on, and I am sure you can think of many others to add to this list. But one of the skills a writer must master is one that I don’t think is often mentioned: waiting.

As Jane Austen wrote in Mansfield Park. “When people are waiting, they are bad judges of time, and every half minute seems like five.”

Many a writer waits for inspiration. That’s not usually my problem but it does happen, and one must learn to respect that. There is, however, waiting while in the very process of writing. One often comes upon the phrase—or something similar—“After a decade since their last book author X is now—at last—about to publish a new work.” Both writer and faithful reader have been waiting.

The fastest time I ever experienced a book written and published was Encounter at Easton. Start to finish, eleven months! That’s the only time that happened. I don’t even know why.

Let it be said the actual publication of a new book can take a very long time. Though they seem slight, picture books can take years to be published. My very first novel, No More Magic was scheduled to be published at a certain date, only to be postponed for a year. No reasons were given, and I was too new to publishing to have the temerity to ask why. It was, to be sure, a long wait.

There are many other points in the publishing process where waiting is the norm. Submit a manuscript to an editor, and there can be a long time to wait before you get any response, yea or nay.

A book can be accepted but there can be a long time to wait before a contract is drawn up.

A book can be accepted, a contract is drawn up and signed, and still, an author can wait months before he/she receives editorial notes. Indeed, the back and forth between editor and writer, even as the process goes forward, almost inevitably can require much waiting.

In the years I have been publishing, the waiting has become both more common and extended. Let it be said, sometimes these wait times are explained, but just as often—in my experience—they are not. Over time the delays have nothing to do with the book but in the life of an all-to-human editor. It may be because the editor is overworked. That’s become usual. Editors can—and often are—working on a large number of books—simultaneously.

Sometimes delays occur because the actual publishing of a book takes place outside the United States. That is to say: supply chain problems. I seem to recall that during the past two years a ship sunk mid-ocean, a ship filled with newly published books.

During the pandemic there were printing press log jams, the log being books.

Since we speak of waiting, it’s almost obligatory to have a bit from Samuel Beckett’s play, Waiting for Godot.

Vladimir: Well? What do we do?

Estragon: Don’t let’s do anything. It’s safer.

Not, in my opinion, wise advice. Indeed, the advice I most often give to a new author who has just had a book (often a first) submitted is, “Start another book.” And for those of us who have published and are waiting for whatever, the advice is the same.

Keep writing.

November 7, 2023

Revising 80 or more times

I had spent my morning going over a new book—revising it–when I got a letter from a reader named “Molly.” It read, in part:

Dear Avi. “You said somewhere that you revise your books eighty or more times. Is that true? Why do you do that? Do I have to do that?”

Dear Molly: Every writer needs to find her or his way of creating the best piece of writing they can. There is no set of rules that fits all. A famous writer once told me she couldn’t start writing until she knew the first sentence. Another famous writer told me she couldn’t start writing until she had the last sentence of the book. I myself rewrite the first sentences many times.

Even the way one writes differs.

The late, great Bob Cormier wrote his books by hand, and it was his wife who transcribed his words with a typewriter. I qknew a writer who wrote paragraph by paragraph on 3 X 5 index cards and then assembled his whole text. I recall Richard Peck telling me he wrote his manuscripts on a portable manual typewriter. When I truly began to write it was by way of manual typewriters, heavy Royal typewriters only thank you, that I searched out in flea markets. Aside from loving the action of the keys, they had a marvelous ring! when you threw the carriage back. I still miss that.

I think my own way of writing has been heavily influenced by the fact that I have dysgraphia.

The NIH defines dysgraphia as: “A neurological disorder characterized by writing disabilities. Specifically, the disorder causes a person’s writing to be distorted or incorrect. In children, the disorder generally emerges when they are first introduced to writing. They make inappropriately sized and spaced letters or write wrong or misspelled words, despite thorough instruction. For example, writing “boy” for “child.”

Just today, as I went over a new text (which I had already gone over many times), I found the words “shard hake.” What in the world did that mean? I looked at it and realized it should have been a “hard shake.”

Or, as a fond aunt of mine once said of my writing; I could “spell a four-letter word wrong five different ways.”

That meant as I wrote I found the need to go over my writing repeatedly to find mistakes. I was constantly retyping manuscripts.

So, part of my many, many reviews of the text happen because I want to find errors and correct them. That marvelous day when I first learned to use a computer meant I wasn’t endlessly retyping manuscripts. The day I discovered how to use a spell checker was truly a life-changing event for me.

All that said, what I learned is that all that constant reviewing and rewriting of my work led to an improvement of the text itself. It stopped being a corrective process and became an enhancement process. That is, my understanding of my text was enriched and deepened. I came to understand my characters better. I began to know them so well that they began to tell me what to say, and how they should react. My text became tighter. My plots evolved better. That’s to say my writing improved.

But beyond all else, my constant revisions came out of my ability to read well.

Being a voracious reader for most of my life I have developed an intuitive sense of good writing. That means as I read and reread my writing I constantly made changes so that my work reads better. That “better” encompasses so many things, from the tempo and rhythm of the plot to subtle aspects of character. It’s what makes writing—reading—good.

Ultimately, the reason I rewrite so much is because I’m trying to write well. It’s hard to write well. That will be true for every writer no matter who you are.

So, Molly, the process you develop for your writing is something you will have to learn for yourself. All you need to do is find a way to write well. It’s as simple—and hard—as that.

Good luck!

Your writing friend,

Avi

P.S. I rewrote this letter eight times. Is it okay?

October 31, 2023

Give Me Some Space

If you think as I do, that the physical book can be a form of art, then typography (a 1664 word) has been defined as, “The action or process of printing; especially the setting and arrangement of types and printing from them; typographical execution; hence, the arrangement of words on a page,” is vital to the art of bookmaking.

Beginning with Gutenberg, the type was set letter by letter, with the spacing (called leading) between letters and words. This had a vital impact on the eye. If you have ever seen a page of beautifully set hand type I think you will recognize it as, well, very beautiful to the eye.

It is a fact that as I type these words on my computer the typography is done for me. Yes, I am given a choice of spacing: “Normal, Expanded, and Condensed.” I can make the letters bold. I can also change the spacing between lines. And my computer gives me a fairly large choice of fonts.

Caslon typeface [source: Wikipedia]

Caslon typeface [source: Wikipedia] My own favorite font is an 18th-century type called Caslon, named after William Caslon the Englishman who designed it in 1722. I find it clear, and graceful, with subtle elegance.

You can see Caslon online, and even add it to your computer fonts from a number of sources.

I can recall fondly a chat I once had with Kevin Henkes, about how we both liked to choose the font for the manuscript we were composing. We agreed that, as we wrote, it made a difference. I also admit, I’m not sure why.

All of this is a preface to a fascinating article I came upon in The Atlantic Magazine (May 2018) titled, “The Scientific Case for Two Spaces After a Period.”

It appears that Skidmore College’s Department of Psychology did a study and determined that “All readers benefit from having two spaces after periods.” The researcher, Rebecca Johnson, said “Increased spacing [of text] has shown to help facilitate processing in a number of reading studies removing the spaces between words altogether drastically hurts our ability to read fluently while increasing the amount of space between words helps us process the text.”

Let it be said, however, that The Chicago Manual of Style and The Modern Language Association Style Manual, opt for one space after the period.

I did an experiment. I took the computer manuscript of my current project and got the computer to change the spacing of all my sentences from one space after the period, to two.

It took a matter of seconds.

To my eyes it did make a difference, making the text much easier to read.

Is this important? No. But in a world full of ghastly news, it’s delightful to debate: Two spaces or one after a period.

Do weigh in.

But for my part, if you hear me say, “Hey, pal, gimme some space,” you’ll know what I mean.

Avi's Blog

- Avi's profile

- 1703 followers