Patrick Taylor's Blog, page 5

February 6, 2012

Troubles at the Table

First published in Stitches magazine, March 1996

O'Reilly expounds on the Great Wall of Ulster

Doctor Fingal Flaherty O'Reilly was rarely lost for an opinion, and not only on matters medical. Now it's just possible that you've noticed during the last 25 years that there has been a touch of internecine unpleasantness going on in the North of Ireland. Although at this time of writing peace seems to have broken out over there, when I was working for O'Reilly there were nights when I began to wonder when they were going to issue the civil war with a number, like WW1 or WW2. Many great minds had done their collective best to try to come up with a solution. Alas, in vain.

After another huge bomb had remodelled another chunk of Belfast, I foolishly asked O'Reilly, over supper one evening, what he thought could be done about the Troubles.

He paused from disarticulating the roast fowl, stared at me over his half-moon spectacles and waved vaguely in my general direction with a slice of breast that was impaled on the carving fork. "Which troubles?

I toyed with my napkin, feeling a great urge to have bitten my tongue out — before I'd asked the question. It had been a busy day and Mrs. Kincaid's roast chicken would have gone a long way to easing the hunger pangs. By the way O'Reilly had asked his question in reply, I could tell that he was ready to expound at some length, and I had a horrible suspicion that he might forget that he was meant to be carving.

"Come on, man." He laid the fork and its toothsome burden back on the plate. "Which troubles?"

I sighed. Dinner, it seemed, was going to be late. "The Troubles. The civil war."

He picked up the fork and expertly dislodged the slice of meat with the carving knife — dislodged it onto his own, already heaped plate. "Oh. Those troubles."

No, Fingal. The outbreak of foot and mouth disease on Paddy Murnaghan's farm, the civil war in Biafra, or the fact that you seem to have forgotten that locums, like gun dogs, need to be fed at least once a day. I kept my thoughts to myself. Captain Bligh and his few loyal crew members had rowed a long-boat about 2,000 miles to East Timor existing on one ship's biscuit. Perhaps if I let O'Reilly expound for a while he might eventually see fit to toss me the odd crumb of nourishment.

A spoon disappeared into the nether end of the bird and re-appeared full of steaming sage and onion stuffing.

"Those troubles." O'Reilly hesitated, trying to find room on his plate between the slices of breast and the roast potatoes before deciding to dump the stuffing at random on top of the pile. He replaced the spoon in the bird with the finesse of a proctologist. "Those troubles. I reckon there's a pretty simple solution. Pass the gravy."

I did so. "Fingal …" I tried, hoping at least to encourage him to start serving me as he held forth. Try interrupting the incoming tide in the Bay of Fundy.

"Simple. Now. You tell me: what are the three most pressing problems in Northern Ireland?" He ingested a forkful and masticated happily while waiting for my reply.

How about pellagra, scurvy, and beri-beri in underpaid, underfed junior doctors?

"Come om, come om …" His words were a little garbled. He swallowed. "Right, I'll tell you. Unemployment, falling tourism, and the brave lads who like to make things go bang."

I was drowning in my own saliva, watching him tuck in. He pointed at me with his fork. "The solution is a Great Wall of Ulster."

"A what?"

"Great Wall of Ulster." He pulled the half-carved chicken towards himself, stood, expertly dissected the remaining drumstick and laid three roast potatoes between the severed limb and the rest of the carcass. "Now look. The thigh there's Ulster and the tatties are my wall."

Brilliantly pictorial, I had to admit, but I really would have forgone this lesson in Political Science if a bit of his improvised Ulster or the rest of Ireland, if that was what the breast was meant to represent, could somehow have been transported to my still-empty plate.

"Now. Tourism. The tourists would come for miles to see the Great Wall." He used the carving knife to line the tubers up more straightly. "The unemployed would have had to build it in the first place, of course."

My unemployed stomach let go with a gurgle like the boiling mud pits of New Zealand.

"You're excused," said O'Reilly. "Finally," — he squashed one of the potatoes with the spoon he'd used to help himself to stuffing — "the brave banging lads could blow it up to their hearts' content and" — he paused and replaced the mashed spud with a fresh one —"the unemployed could be kept occupied rebuilding." He sat beaming at me. "Told you it was simple."

I hastened to agree, hoping that now he'd finished I might finally get something to eat.

The door opened and Mrs. Kincaid stuck her head into the dining room. "Can you come at once, Doctor Taylor? There's been an accident."

January 29, 2012

Kinky

Every practice should have a triage specialist like her

Doctor Fingal Flaherty O'Reilly wasn't the only character in the practice. Mrs. Kincaid, widow, native of County Kerry, known to one and all as "Kinky," functioned as his housekeeper-cum-receptionist-cum-nurse. She was a big woman, middle-aged, with big hands and blue eyes that could twinkle like the dew on the grass in the morning sun when she was in an expansive mood — or flash like lightning when she was enraged. She treated Doctor O'Reilly with due deference when he behaved himself and sub-Arctic frigidity when he didn't. She was the only person I knew who could bring him to heel. In her native county she would have been known as "a powerful woman."

When she was acting in her nursing role, Kinky's speciality was triage. Cerberus at the gates to Hades might have done a fair to middling job keeping the unworthy in the underworld, but when it came to protecting her doctors' time from the malingerers of the town, Kinky made the fabled dog look like an edentulous pussy cat. Not only did she get rid of them, she did so with diplomatic skills that would have been the envy of the American ambassador to the Court of St. James.

I began to appreciate her talents one January evening. It had been a tough week. We were in the middle of a 'flu epidemic and O'Reilly, who'd been without much sleep for about four days, had prevailed upon me to come and help him out. By the week's end both of us were knackered. We were sitting in the surgery, me on the examination couch, O'Reilly slumped in the swivel chair. The last patient had left and as far as I knew no emergency calls had come in. O'Reilly's usually ruddy complexion was pallid and his eyes red-rimmed, the whole face looking like two tomatoes in a snowbank. I didn't like to think about my own appearance. He massaged his right shoulder with his left hand. "God," he said, "I hope that's the last of it for tonight." As he spoke the front door bell rang. "Bugger!" said O'Reilly.

I started to rise but he shook his head. "Leave it. Kinky will see who it is."

The door to the surgery was ajar. I could hear the conversation quite clearly, Kinky's soft Kerry brogue contrasting sharply with harsher, female tones. I thought I recognized the second speaker, and when I heard Kinky refer to her as "Maggie," I realized that the caller was the woman who'd come to see O'Reilly complaining of headaches that were located about two inches above the crown of her head. She was in and out of the surgery on a weekly basis. The prospect of having to see her was not pleasant. I needn't have worried.

"The back is it, Maggie?" Kinky's inquiry was dulcet.

"Something chronic," came the reply.

"Oh dear. And how long has it been bothering you?"

"For weeks."

"Weeks is it?" The concern never wavered. "Well, we'll have to get you seen as soon as we can."

I shuddered, for it was my turn to see the next patient, but O'Reilly simply smiled, shook his head and held one index finger in front of his lips.

"Pity you'll have to wait. The young doctor's out on an emergency. He shouldn't be more than two or three hours. You will wait, won't you?"

I heard the sibilant indrawing of breath and could picture Maggie's frustration. I heard her harrumph. "It's the proper doctor that I want to see, not that young lad."

So much for the undying respect of the citizens for their medical advisors. I glanced at O'Reilly and was rewarded with a smug grin.

"Ah," said Kinky, "Ah, well now, that's the difficulty of it. Doctor O'Reilly's giving a pint of his own blood this very minute, the darling man."

"Mrs. Kincaid" — Maggie didn't sound as if she was going to be taken in — "that has to be the fifth pint of blood you've told me about him giving this month."

I waited to see how Kinky would wriggle out of that one. I needn't have worried, as I heard her say with completely convincing sincerity, "And is that not what you'd expect from Doctor O'Reilly, him the biggest-hearted man in the town. Goodnight. Maggie. I heard the door close. As I told you, O'Reilly wasn't the only character in the practice.

January 20, 2012

Galvin’s Ducks

“That man Galvin’s a bloody idiot!” Thus spake Doctor Fingal Flaherty O’Reilly. He was standing in his favourite corner of the bar of the Black Swan Inn, or, as it was known to the locals, The Mucky Duck. O’Reilly’s normally florid cheeks glowed crimson and the tip of his bent nose paled. Somehow rage seemed to divert the blood flow from his hooter to his face. I thought it politic to remain silent. I’d seen the redoubtable Doctor O’Reilly like this before.

He hadn’t seemed to be his usual self when we’d repaired to the hostelry after evening surgery, and now, after his fourth pint, whatever had been bothering him was beginning to surface. “Raving bloody idiot,” he muttered, taking a generous swallow of his drink and slamming the empty glass on the counter.

After six months as his weekend locum and part-time assistant, I’d learned my place in O’Reilly’s universe. I nodded to Brendan the barman, who rapidly replaced O’Reilly’s empty glass with another full of the velvet liquid product of Mr. Arthur Guinness and Sons, St. James’s Gate, Dublin.

“Ta,” said O’Reilly, the straight glass almost hidden by his big hand. “I could kill Seamus Galvin.” He rummaged in the pocket of his rumpled jacket, produced a briar, stoked it with the enthusiasm of Beëlzebub preparing the coals for an unrepentant sinner, and fired up the tobacco, making a smokescreen that would have hidden the entire British North Sea fleet from the attentions of the Panzerschiff Bismark.

I sipped my shandy and waited, trying to remember if I’d seen the patient in question.

“Do you know what that benighted apology for a man has done?”

From the tone of O’Reilly’s voice, I assumed it must have been some petty misdemeanour — like mass murder perhaps. “No,” I said, helpfully.

O’Reilly sighed. “He has Mary’s heart broken.”

Now I remembered. Seamus Galvin and his wife Mary lived in a cottage at the end of one of the lanes just outside the small Ulster town where O’Reilly practised. Galvin was a carpenter by trade and a would-be entrepreneur. I’d seen him once or twice, usually because he’d managed to hit his thumb with one of his hammers. I said the man was a carpenter; I didn’t say he was a good carpenter.

“Broken,” said O’Reilly mournfully, “utterly smashed.”

This intelligence came as no great surprise. Mary Galvin was the sheet anchor of the marriage, bringing in extra money by selling her baking, eggs from her hens, and the produce of her vegetable garden. Galvin himself was a complete waster.

O’Reilly prodded my chest with the end of his pipe. “I should have known a few weeks ago when I saw him and he was telling me about his latest get-rich scheme.” The big man grunted derisively. “That one couldn’t make money in the Royal Mint.”

I could only agree, remembering Galvin’s previous failed endeavours. His “Happy Nappy Diaper Service” had folded. No one in a small town could afford the luxury of having someone else wash their babies’ diapers. Only the most sublime optimist could have thought that a landscaping company would have much custom in a predominantly agricultural community. Galvin had soon been banished from his “Garden of Eden” lawncare business — presumably because his encounters with the fruit of the tree of knowledge had been limited. I wondered what fresh catastrophe had befallen him.

O’Reilly beat carelessly at an ember that had fallen from the bowl of his pipe onto the lapel of his tweed jacket. “Mary’s the one with sense. She was in to see me a couple of weeks ago. She’s pregnant.” He inspected the charred cloth. “I’ve known her since she was a wee girl. I’ve never seen her so happy.” His craggy features softened for a moment. “She told me her secret. She’d been saving her money and had enough for Seamus and herself to emigrate to California.”

“Oh,” I said.

“Aye,” said O’Reilly, “she has a brother out there. He was going to find Seamus a job with a construction company.”

I’d read somewhere that California was prone to earthquakes and for a moment thought that this unfortunate geological propensity had been transmitted to Ulster before I realized that the pub’s attempt to shimmy like my sister Kate was due to O’Reilly banging his fist on the bar top.

“That bloody idiot and his bright ideas.” O’Reilly’s nose tip was ashen. “He’s gone into toy making. He thinks he can sell rocking ducks — rocking ducks.” He shook his head ponderously. “Mary was in tonight. The wee lass was in tears. He’d taken the money she’d saved and went and bought the lumber to make his damn ducks. That man Galvin’s a bloody idiot.”

O’Reilly finished his pint, set the glass on the counter, shrugged and said just one more word, “Home.”

About a month later, I met Mary Galvin in the High St. She stopped me and I could see she was bubbling with excitement.

“How are you, Mary?”

“Doctor, you’ll never believe it!” She had wonderfully green eyes and they were sparkling. “A big company in Belfast has bought all of Seamus’ rocking ducks, lock stock and barrel.” She patted her expanding waistline. “The three of us are off to California next week.”

I wished her well, genuinely pleased for her good fortune. It wasn’t until I’d returned to O’Reilly’s house that I began to wonder. He was out making a house call. For the last week he’d taken to parking his car on the street. No. No, he wouldn’t have …?

When I opened the garage door, a bizarre creature toppled out from a heap of its fellows. The entire space was filled to the rafters with garishly painted ducks — rocking ducks. It only took a moment to stow the one that had made a bid for freedom and close the door.

When I introduced Doctor O’Reilly, I described him as, among other things, a crypto-philanthropist. Now you know why.

Galvin's Ducks

"That man Galvin's a bloody idiot!" Thus spake Doctor Fingal Flaherty O'Reilly. He was standing in his favourite corner of the bar of the Black Swan Inn, or, as it was known to the locals, The Mucky Duck. O'Reilly's normally florid cheeks glowed crimson and the tip of his bent nose paled. Somehow rage seemed to divert the blood flow from his hooter to his face. I thought it politic to remain silent. I'd seen the redoubtable Doctor O'Reilly like this before.

He hadn't seemed to be his usual self when we'd repaired to the hostelry after evening surgery, and now, after his fourth pint, whatever had been bothering him was beginning to surface. "Raving bloody idiot," he muttered, taking a generous swallow of his drink and slamming the empty glass on the counter.

After six months as his weekend locum and part-time assistant, I'd learned my place in O'Reilly's universe. I nodded to Brendan the barman, who rapidly replaced O'Reilly's empty glass with another full of the velvet liquid product of Mr. Arthur Guinness and Sons, St. James's Gate, Dublin.

"Ta," said O'Reilly, the straight glass almost hidden by his big hand. "I could kill Seamus Galvin." He rummaged in the pocket of his rumpled jacket, produced a briar, stoked it with the enthusiasm of Beëlzebub preparing the coals for an unrepentant sinner, and fired up the tobacco, making a smokescreen that would have hidden the entire British North Sea fleet from the attentions of the Panzerschiff Bismark.

I sipped my shandy and waited, trying to remember if I'd seen the patient in question.

"Do you know what that benighted apology for a man has done?"

From the tone of O'Reilly's voice, I assumed it must have been some petty misdemeanour — like mass murder perhaps. "No," I said, helpfully.

O'Reilly sighed. "He has Mary's heart broken."

Now I remembered. Seamus Galvin and his wife Mary lived in a cottage at the end of one of the lanes just outside the small Ulster town where O'Reilly practised. Galvin was a carpenter by trade and a would-be entrepreneur. I'd seen him once or twice, usually because he'd managed to hit his thumb with one of his hammers. I said the man was a carpenter; I didn't say he was a good carpenter.

"Broken," said O'Reilly mournfully, "utterly smashed."

This intelligence came as no great surprise. Mary Galvin was the sheet anchor of the marriage, bringing in extra money by selling her baking, eggs from her hens, and the produce of her vegetable garden. Galvin himself was a complete waster.

O'Reilly prodded my chest with the end of his pipe. "I should have known a few weeks ago when I saw him and he was telling me about his latest get-rich scheme." The big man grunted derisively. "That one couldn't make money in the Royal Mint."

I could only agree, remembering Galvin's previous failed endeavours. His "Happy Nappy Diaper Service" had folded. No one in a small town could afford the luxury of having someone else wash their babies' diapers. Only the most sublime optimist could have thought that a landscaping company would have much custom in a predominantly agricultural community. Galvin had soon been banished from his "Garden of Eden" lawncare business — presumably because his encounters with the fruit of the tree of knowledge had been limited. I wondered what fresh catastrophe had befallen him.

O'Reilly beat carelessly at an ember that had fallen from the bowl of his pipe onto the lapel of his tweed jacket. "Mary's the one with sense. She was in to see me a couple of weeks ago. She's pregnant." He inspected the charred cloth. "I've known her since she was a wee girl. I've never seen her so happy." His craggy features softened for a moment. "She told me her secret. She'd been saving her money and had enough for Seamus and herself to emigrate to California."

"Oh," I said.

"Aye," said O'Reilly, "she has a brother out there. He was going to find Seamus a job with a construction company."

I'd read somewhere that California was prone to earthquakes and for a moment thought that this unfortunate geological propensity had been transmitted to Ulster before I realized that the pub's attempt to shimmy like my sister Kate was due to O'Reilly banging his fist on the bar top.

"That bloody idiot and his bright ideas." O'Reilly's nose tip was ashen. "He's gone into toy making. He thinks he can sell rocking ducks — rocking ducks." He shook his head ponderously. "Mary was in tonight. The wee lass was in tears. He'd taken the money she'd saved and went and bought the lumber to make his damn ducks. That man Galvin's a bloody idiot."

O'Reilly finished his pint, set the glass on the counter, shrugged and said just one more word, "Home."

About a month later, I met Mary Galvin in the High St. She stopped me and I could see she was bubbling with excitement.

"How are you, Mary?"

"Doctor, you'll never believe it!" She had wonderfully green eyes and they were sparkling. "A big company in Belfast has bought all of Seamus' rocking ducks, lock stock and barrel." She patted her expanding waistline. "The three of us are off to California next week."

I wished her well, genuinely pleased for her good fortune. It wasn't until I'd returned to O'Reilly's house that I began to wonder. He was out making a house call. For the last week he'd taken to parking his car on the street. No. No, he wouldn't have …?

When I opened the garage door, a bizarre creature toppled out from a heap of its fellows. The entire space was filled to the rafters with garishly painted ducks — rocking ducks. It only took a moment to stow the one that had made a bid for freedom and close the door.

When I introduced Doctor O'Reilly, I described him as, among other things, a crypto-philanthropist. Now you know why.

January 4, 2012

Happy New Year! Here's the second O'Reilly column from Stitches magazine

The Lazarus Manoeuvre

How the young Doctor O'Reilly earned the

respect of his community

We were sitting

in the upstairs lounge of Doctor O'Reilly's house at the end of the day.

Himself was tucking contentedly into his second large whiskey. "So," he

demanded, "how do you like it?"

Being a little uncertain whether he was asking about the spectacular view through the

bay window to Belfast Lough, the small sherry I was sipping or the general

status of the universe, I countered with an erudite, "What?"

He fished in the external auditory canal of one thickened, pugilist's ear with the

tip of his right little finger and echoed my sentiments: "What?"

I thought this conversation could become mildly repetitive and decided to broaden

the horizons. "How do I like what, Doctor O'Reilly?"

He extracted his digit and examined the end with all the concentration and

knitting of brows of a gorilla evaluating a choice morsel. "Practice here, you

idiot. How do you like it?"

My lights went on. "Fine," I said, as convincingly as possible. "Just fine."

My reply seemed to satisfy him. He grinned, grunted, hauled his 20 stone erect,

wandered over to the sideboard and returned carrying the sherry decanter. He

topped up my glass. "A bird can't fly on one wing," he remarked.

I refrained from observing that if he kept putting away the whiskey at his usual

rate he'd soon be giving a pretty fair imitation of a mono-winged albatross in

a high gale, accepted my fresh drink and waited.

He returned the decanter, ambled to the window and took in the scenery with one

all-encompassing wave of his arm. "I'd not want to live anywhere else," he

said. "Mind you, it was touch and go at the start."

He was losing me again. "What was, Doctor O'Reilly?"

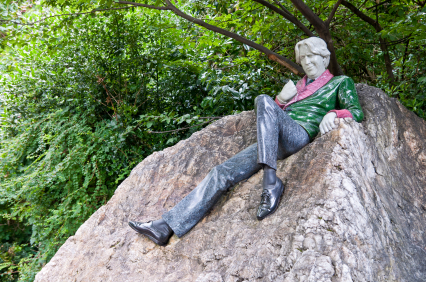

"Fingal, my boy. Fingal. For Oscar." He gave me one of his most avuncular smiles.

I couldn't for the life of me see him having been named for a small, gilded

statuette given annually to movie stars. "Oscar, er, Fingal?" I asked.

He shook his head. "No. Not Oscar Fingal. Wilde."

He did this to me. Every time I thought I was following him he'd change tack,

leaving me in a state of confusion bordering on that usually felt by people

recovering from an overdose of chloroform. "Oscar Fingal Wilde, Fingal?"

I should have stuck with, "Doctor O'Reilly." I could tell by the way the tip of

his bent nose was beginning to whiten that he was becoming exasperated. He

shook his head. "Oscar … Fingal … O'Flahertie … Wills … Wilde."

I stifled the urge to remark that if you put an air to it you could sing it.

He must have seen my look of bewilderment. The ischaemia left his nose. "I was

named for him. For Oscar Wilde."

The scales fell from my eyes. "I see."

"Good. Now where was I?"

"You said, 'It was touch and go at the start.'"

"Oh yes. Getting the practice going. Touch and go." He sat again in the big

comfortable armchair, picked up his glass of whiskey and looked at me over the

brim. "Did I ever tell you how I got started?"

"No," I said, settling back in my own chair, preparing myself for another of his

reminiscences, for another meander down the byways of O'Reilly's life.

"I came here in the early forties.

Took over from Doctor Finnegan."

I hoped fervently that we weren't about to embark on the genealogy of James Joyce, and was relieved to hear O'Reilly continue, "He was a funny old bird."

Never, I thought, but kept the thought to myself.

O'Reilly was warming up now. "Just before he left, Finnegan warned me about a local

condition of cold groin abscesses. He didn't understand them." O'Reilly took a

mouthful of Irish, savoured it and swallowed. "He explained to me that when he

lanced them he either got wind or shit, but the patient invariably died."

O'Reilly chuckled.

I was horrified. My mentor's predecessor had been incising inguinal hernia.

"That's why it was touch and go," said O'Reilly. "My first patient had the biggest

hernia I've ever seen. When I refused to lance it, like good old Doctor

Finnegan, the patient spread the word that I didn't know my business." He sat

back and crossed one leg over the other. "Did you ever hear of Lazarus?"

"Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Lazarus?" I asked.

"Don't be impertinent." He grabbed my, by-now-empty, glass and headed back to the sideboard. The delivery of a fresh libation, and one for himself, signalled that he hadn't been offended. "No, the Biblical fellow that Jesus raised from the dead." He sat.

"Yes."

"That's how I got my start."

Was it the sherry or was I really losing my mind? Whatever his skills, I doubted

that Doctor O'Reilly had actually effected a resurrection. "Go on," I asked for

it.

"I was in church one Sunday, hoping that if the citizens saw that I was a good

Christian they might look upon me more favourably."

The thought of a pious O'Reilly seemed a trifle incongruous.

"There I was when a farmer in the front pew let out a yell like a banshee, grabbed his

chest and keeled over." To add drama to his words O'Reilly stood, arms wide. "I

took out of my pew like a whippet. Examined him. Mutton. Dead as mutton."

I knew that CPR hadn't been invented in the forties. "What did you do?"

O'Reilly lowered his arms and winked. "I got my bag, told everyone to stand back, and

gave the poor corpse an injection of whatever came handy. I listened to his

heart. 'He's back,' says I. You should have heard the gasp from the

congregation."

He sat down. "I listened again. 'God,' says I, 'He's going again,' and gave the poor bugger another shot." O'Reilly sipped his drink. "I brought him back three times

before I finally confessed defeat."

Innocence is a remarkable thing. "Did you really get his heart started?"

O'Reilly guffawed. "Not at all, but the poor benighted audience didn't know that. Do you know I actually heard one woman say to her neighbour, 'The Lord only brought

Lazarus back once and the new doctor did it three times.'" He headed for the sideboard again. "I told you it was touch and go at the start, but the customers started rolling in after that — will you have another?"

Jan. 96

December 21, 2011

A Christmas Story by Patrick Taylor

A CHRISTMAS STORY

I was told some folks who are enjoying the Irish Country series have asked for a Christmas story so I've written one. Like the rest of the books I've added a list of unfamiliar words and a recipe—one simple enough for kiddies to make without risking burning down the whole house.

I hope you enjoy this. It comes with my wishes for a very Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year.

Patrick Taylor,

Cootehall,

Boyle,

County Roscommon

Sleigh Bells Ring

by

Patrick Taylor

He stood in the living-room doorway watching. The chimney sweep who was working at Colin Brown's Daddy and Mammy's house in Ballybucklebo fascinated nine-year old Colin. Maybe, he thought, when I grow up I'll be a chimney sweep. They can get as dirty as they like and nobody minds. My mammy's always going on about washing behind my ears or telling me, "There's enough muck on the back of your neck to make a lazy bed and grow potatoes, Colin Brown, so there is."

Colin could see the back of Mr. Gilligan's neck because he was kneeling on a big canvas sheet that lay like a second carpet in front of the living room fireplace. The soot between the collar of his boiler suit and his cut-short grey hair could probably have sustained a crop of barley—and nobody gave off to him.

Sweeping, Colin decided, was definitely a job option—after engine driving.

All the furniture had been moved to one end of the room and covered in sheets. A special wide piece of cloth was fixed in front of the grate. It had a hole in the centre.

"You're going to screw that there," Colin pointed at the brass fitting on one end of an eight foot bamboo rod, "into that socket on the end the rod that goes through the hole in the cloth." Colin knew that somewhere up the flue a big, flat, circular, brush was being forced up by a series of linked lengths of bamboo.

"That's right, Colin."

Colin grinned. He liked being right. Always had.

He was aware of someone standing beside him. He half turned. "What do you want, Nancy?" he asked his six-year old sister.

Nancy had her long blonde hair tied up with green ribbons in two bunches that hung from the sides of her head. Her cornflower-blue eyes were set in an oval face and smiled out past a button nose.

"Can I watch too, please?"

He grinned at her. "'Course you can, but stay here with me. Mammy wouldn't like you to get your dress dirty."

"Thank you." She smiled at him and took his hand.

Colin wasn't too fond of girls. He would have been horrified if any of his friends had seen him with her hand in his, but Nancy was different. He didn't understand why, but he always felt—well—big-brotherly around her. Protective. Perhaps, he though, it's because you are her big brother, you eejit.

"It's a good thing Mr. Gilligan came, isn't it, Colin?"

"Why?"

"It's Christmas Eve tomorrow and Santa's coming." She smiled up at him. "And we get to send our letters tonight when Daddy lights the fire. I'm going to ask Santa for a dolls' pram and a skipping rope."

Now she was old enough to do it herself Colin wouldn't have to write a note for Nancy then put it in the fire. Even after it had burned you could still make out the words as the charred paper whirled up the chimney and straight to the North Pole. His was going to ask for a real two-wheeler bike.

She nodded toward the sweep. "Daddy said unless the chimney was swept he couldn't light a fire because of the bll…bll…" She stumbled over the right word.

"Blowdowns we had last night," Colin found it for her. Well. She was only little. "Aye. Daddy said there was too much soot in the flue and it could catch on fire and set the whole house alight. So it had to be swept. It's not been done for a couple of years."

"Two-and-a-half," said Mr. Gilligan. "It was June 1961 the last time I done the job. It needed doing." He looked straight at Nancy. "Never mind your letter not getting to Santa. How do you think he'd like to come down a chimney that's clogged with soot?"

"Oooh," she said and her eyes widened. "He'd get all dirty."

"I think," said Colin, with all the weight of his nine years, "I think he comes in through the front door. I don't see how he could get Donner and Blitzen and all the other reindeer, them all harnessed with their jingle bells, and his sleigh up on our wee roof."

"Do you not?" asked Mr. Gilligan. "Now there's a thing."

Colin was going to argue and say that it would be much easier for a man with Santa's big tummy to come in through the door. He'd never fit through the flue. Then he saw Nancy looking puzzled. He kept his mouth shut.

She frowned and said, "Daddy says he comes down the chimney. That's why we leave him egg-nog and biscuits and carrots for his reindeer. We put them in the hearth and they're always gone in the morning. He does come down the flue. So there."

"You're likely right," said Colin, but privately he was not convinced. He turned to the sweep. "Are you nearly finished?"

Mr. Gilligan screwed in one more rod. "Aye. Just about, but I'm going to need your help."

"Wheeker," Colin said. "Can I push on the rods like you?"

Mr. Gilligan laughed. "That's not what I need help with."

Colin sighed.

The sweep stood up. "Come on outside, the pair of you." He headed for the door and Colin, still holding Nancy's hand, followed. He could smell the soot on the man's dungarees.

"Get your coats and hats and gloves," Mr. Gilligan said.

Colin helped Nancy into hers then put on his own. He wondered what he was going to be asked to do.

Outside in the garden he was glad they had dressed warmly. Although the sun shone down from an enamel-blue sky even at two in the afternoon there was still a heavy rime of frost sparkling on the little lawn. The ice on a puddle in the path crackled when Colin trod on it.

Across the Shore Road and past the sea wall the wind chivvied the waves of Belfast Lough like a sheep dog chases the sheep. The rollers turned to foam as they rushed up the shallowing shore. The breakers rolled the pebbles on the shingly beach making a noise like a thousand kettle drums.

It was nippy enough out here. Colin glanced at Nancy. Already her nose had turned red. He hoped for her sake they'd not have to stay out too long.

"Right," said Mr. Gilligan. "First of all I have to go up on the roof." He pointed to the chimney pots. "That one there is the pot for the living room."

Colin looked. It was funny, he though, he'd never really paid any attention to chimneys.

"That wire netting has to come off." Mr. Gilligan said, "because the brush has to get out."

"I see," Colin said, staring at a conical wire mesh contraption sitting on top of the chimney pot. "Daddy says it's to stop jackdaws nesting in the chimney."

"That's right. So I'm going to nip up my ladder, take the wire off then I'm going back inside. Your job…both…of you is to watch until my brush pops out of the chimney then run back in and tell me."

"We'll do that, won't we Nancy."

She smiled and nodded.

The sweep turned, then half-turned back. "Just one wee thing, Colin."

"What?"

"Are you quite sure Santa can't get his reindeer on your roof?"

"I…" Colin was. Absolutely convinced. That wee roof? Eight big reindeer? No way. He glanced at Nancy who was listening to every word and frowning. He knew she wanted to believe Father Christmas came down the chimney. "…I don't know," he said.

Mr. Gilligan smiled. "I'll only be a couple of ticks." He went up the ladder rung by rung.

Colin watched the sweep cross the neat, yellow thatch, unlatch the bird-preventer, swing it over to one side, then head back to his ladder.

"I think he's awfully brave going up there," Nancy said. "I'd be scared."

"I'd not."

She squeezed his hand. "You're brave too, Colin and you're older than me." She looked deeply into his eyes. "I just took a quare good look at those chimney pots." She swallowed and when next she spoke Colin heard a catch in her voice. "They're awfully wee. Maybe you're right. Maybe Santa does come in through the front door."

He sensed tears were not far away and didn't know what to say.

"Excuse me," Mr. Gilligan said.

Colin hadn't heard him return. He looked at the big man.

"Were you two arguing about whether or not Santa comes down the chimney?"

"Not really arguing," Nancy said sadly. "I think Colin's right."

"Indeed?" said Mr. Gilligan. "Well I found something at the chimney."

Colin frowned.

"I think you should have them Nancy."

He held out his fist, knuckles up and slowly, slowly uncurled his fingers until, when his hand was completely unclenched, there in the palm of his hand lay two silver sleigh bells.

"Now I wonder," said he, "who left these behind and whoever it was what do you think they were they doing up there in the first place?"

And Colin, still inside of himself sure he was right, looked at the wide grin on his little sister's face, and realised that being right didn't always matter. It didn't matter one tuppenny bit.

.

Possibly unfamiliar words or phrases in the order in which they appear

Lazy bed Heaped up row of earth in which potatoes are grown

So there is Phrase added by people in Ulster for emphasis

Boiler suit One piece protective over-garment

Gave off Scolded

Flue Inside of a chimney that the smoke goes up

Eejit Idiot. Often used affectionately

Blowdowns Times when the fire's smoke come back into the room

So there Emphasis. Like, "booh sucks"

Wheeker Terrific

No way It is impossible

Quare Irish pronunciation of queer used to mean "very"

Tuppenny bit Old English coin worth about ½¢

Peppermint Creams

8 oz (225 gms) icing sugar (confectioner's sugar )

1 large egg white

3 or 4 drops peppermint essence

green colouring (optional)

Beat the egg white in a bowl and sift in the icing sugar (through a sieve). Add the peppermint essence and mix into a paste. Sprinkle some icing sugar on a kitchen worktop.

Knead the paste on the worktop and add some more essence if they don't taste minty enough. Then sprinkle more icing sugar on the rolling pin and roll out flat to about a1/4 inch (0.5cm thick).

Using a tiny round or star shaped cutter cut out the peppermint creams and place on a plate covered with greaseproof paper. Then cover with a clean tea towel and leave in the fridge for an hour or so.

You could store them in an airtight box—but they won't last very long.

30

November 28, 2011

Introducing the Wiley O'Reilly

INTRODUCTION

Beauty, it is said, is in the eye of the beholder. So I believe is humour and that is what the following pages deal with; a larger than life rural general practitioner, his young, eager, naive assistant, and the recounting of the misadventures that befell them. As you read, if you behold the mischief, you will find yourself laughing out loud.

The redoubtable Doctor Fingal Flahertie O'Reilly will be known to readers of the Irish Country Doctor novels. In them he is a complex, flawed human being and his doings are either expressed through his own eyes or from the point of view of his young colleague, Doctor Barry Laverty. While there is humour in the novels there is, I trust, also the unfurling of the lives of some real people with the same hopes and fears of all of us, tears, little triumphs, disappointments, and laughter.

Not so with the template for Fingal, who began life with the full glory of the name Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde O'Reilly out of deference to Oscar Wilde. Fingal's brother Lars was initally named, Lars Porsena Fabius Cunctator—a mouthful that would choke a pig, the Marquis Of Ballybucklebo, John MacNeill began as Lord Fitzgurgle. One Presbyterian minister has the monicker of the Reverend MacWheezle. The author must have been influenced by the Dickensian Mr. Fezzywig, Mister Bumble the Beadle and their ilk.

The prototype for O'Reilly got his start as the Oliver Hardy to a straight-man narrator and their function was to poke fun at an all too serious profession, my own. Medicine. Between 1995 and 2001 their monthly doings appeared in Stitches: The Journal of Medical Humour. Thank you publisher Doctor John Cocker and editor Simon Hally.

I chose to cast myself as the teller of the tales for the simple reason that by doing so I could make facetious asides without spoiling the flow of the stories. Once again. I am not the Barry Laverty of the novels.

These columns have been on my files unread for ten years.

Since I started a Facebook page a number of readers have posted their wishes to read the early columns. Here they are, warts and all, exactly in the sequence in which they first appeared. In reading them you will be able to see how Fingal Flahertie O'Reilly and his supporting cast evolved. You will read again in brief some of the story lines that have been developed into full sub-plots in the books. If you know the novels you'll find yourself muttering, "I remember that." You will in essence be indulging in a bit of voyeurism by peering into a writer's sketch book. Look as hard as you like.

There are inconsistencies between the characters here and in the novels and even within these columns and I'll send an autographed copy of one of my works to the first person who can post one glaring discrepancy on my Facebook.

But I hope that you'll not get too engrossed in looking for literary merit. All of this was written tongue in cheek with one goal only. To make the readers laugh. Please feel free to do so.

November 11, 2011

A Word on My Other Books

One 'thank you' to make and one question to answer this week. To Juli Valley who posted a link to my reading and discussing my work, Hola, y muchas gracias, Senora. Si. Habla pocito Espagnol, and it's time to start practising because Dorothy and I will be wintering this year in Tenerife in the Canary Islands, a warm place and very conducive to writing. I drafted the first 20 chapters of An Irish Country Courtship the last time we were there and fully anticipate being hard at work on book 8 this time.

It's hard to believe it will be my eleventh book length work of fiction, and that

brings me to Ann Burchfield's question. Is there any chance the earlier three

which are currently out of print will be re-released? The answer of course is

typically Irish. Yes—and No.

The three books in question are a far cry from the gentle quiet of the now seven novels in the Irish Country series (Six published, one in production) and represent my very early attempts to write fiction. I was living in Belfast when in 1969 the Troubles broke out again. I felt a need to try to capture my own feelings about the horror of the situation. I was heavily influenced at the time by the works of W. Somerset Maugham so I tried to write a short story about a young man caught up in the internecine strife and torn between his allegiance to his

family and his loyalty to the British Army which he had recently joined. That

story, Gerry, never saw the light of day then, but many years later, when I was living in Vancouver, Canada I began to want to write more than research papers, textbooks, and humour columns. I turned back to my first love—the short story, unearthed Gerry, and started to write. I was having a pint with my friend Jack Whyte, author of the Dream of Eagles Arthurian series, the books of the Knights

Templar Trilogy and who is now well into another trilogy, The Guardians, about great Scottish heroes. Back then he'd just had his first novel, The Skystone, published. I asked him to read Gerry and two other short stories and give an opinion. "I think," he said a few days later, "you should keep at it." Then he laughed. That rumbling is a remarkable sound that only he with his glorious baritone voice can make. "I'll tell you what. Just you keep saying to yourself, 'If Whyte can do it so can Taylor.'" Encouragement is a wonderful thing early in a writing career. Without it then I might have packed up, but I kept going and, damn it all, he was right. A Toronto publishing house read my work and announced if I could produce 16 stories they'd publish. The result, Only Wounded: Ulster Stories. appeared in 1997. The stories tried to capture the lives of ordinary people caught up in extraordinary times. The tales are sombre reading.

You may remember that I explained when I wrote An Irish Country Girl that a character from earlier books, Kinky Kincaid kept nagging at me to tell her story. Back in the late nineties a character from Only Wounded, Davy,

did the same. Eventually I told his story—twice. Davy made bombs for the

Provisional IRA and was losing faith in the cause. How that shattered his life

and the lives of those around him appeared in a thriller Pray for Us Sinners in 2000 and was followed by Now and in the Hour of Our Death in 2005

another thriller, but the theme that drove the story was that of lost love. All

three works are in stark contrast to the gentle world of Ballybucklebo. All, I

think, were written to express my horror at how the, no doubt deeply held

beliefs, of both sides led to such futile carnage that took 35 years and 3,268 people dead merely to end up

politically about where things had been in Ulster in 1968. I am proud of my

early works, all now out of print, and fully hope to see them reissued one day.

That's the 'yes.' part of the answer, but there is a question of timing. I

don't think I'm ready to see them in print just yet. One day—but not right now,

so, Anne that's the 'no,' part of the answer. Not yet, but one day. I hope

that's all right.

Slan

leat.

Pat Taylor.

.

November 2, 2011

How O'Reilly Got His Name

Dia duit, or hello again. Once more a reader's question has prompted a blog—and has given me an idea for a bit of labour saving too. Please let me expand, and answer the question first.

Willa Bee Baker wanted to know if Fingal and Flahertie were common names in Ireland and how did O'Reilly get them. I'll tell you.

I first started writing a column in the nineties for a medical magazine, Stitches: The Journal of Medical Humour. Originally I had told stories of my undergraduate days in the faculty of medicine at Queen's University, Belfast. The electronic files for these, alas are lost. After six years the material was beginning to run thin so I asked my editor, Simon Hally, if I could move on to tales from general practice. During my time as a trainee Obs/Gyn I, like most of my contemporaries, moonlighted, filling in at weekends and in the nights for local GPs.

The result was a monthly column about an irascible country GP who was not patterned on any one individual, but on physical and character traits drawn from some of the men, and at that time nearly all physicians were men, for whom I had worked. He became the stock for the Irish Country Doctor novels.

In my novels I like to write in the third person, in the point of view of certain characters. In the columns I cast myself by name as the first person narrator, often bewildered, frequently the butt of the jokes, a Stan Laurel to the principle character's Oliver Hardy. This allowed me, the story-teller, to make asides without indulging in authorial intrusion.

The columns would only work if the main character was larger than life. I believe those of you who have read the Irish Country novels would agree that Doctor O'Reilly is. His surname comes from the Irish Ó'Raghallaigh, 'grandson of Raghallach', thought to be derived from ragh meaning 'race' and ceallach, meaning, 'sociable'—and O'Reilly certainly is. His ancestor who might or might not have been perished at the Battle of Clontarf in 1014.

And my O'Reilly needed a Christian name and middle name.

When I wrote the first column I had been reading Richard Ellman's wonderful biography of Oscar Wilde, that is in full, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde. I stole Fingal (literally, fair foreigner) and Flahertie, dropping the O'which in the Irish system of naming boys indicates, 'grandson of.' In Oscar Wilde's case his O'Flahertie meant, 'grandson of the prince.' O'Reilly's grandfather was a landed gentleman, but Fingal's second name simply means, 'prince.'

In An Irish Country Doctor O'Reilly explains to Barry Laverty that his father, a professor of literature named his son for Oscar Wilde. In A Dublin Student Doctor O'Reilly's father explains to his son why Professor O'Reilly chose the names and those of Fingal's elder brother, Lars Porsena.

Are the names common in Ireland? O'Reilly's progenitors the Reilly's were brilliant businessmen so much so their name became Irish slang for money—hence, a life of Reilly meant, 'being in the money.' Reilly is among the first fifteen names in Ireland. Fingal is fairly common as a boy's name. Flahertie? I've never met anyone with that as a pre-name—except Oscar Wilde—and of course, O'Reilly.

So many folks have wanted to know about my early writing about Fingal Flahertie that very soon I'll be releasing some of my first magazine columns on my website and on Face Book to tide O'Reilly fans through the fallow period until the next novel.

And that, by a circuitous route, brings to me to the labour-saving bit. It's delightful that so many of you are interested enough to ask me questions. I'd love to answer every one individually. I ask you to remember that I spend every working day on the keyboard. One solution, and I hope you can accept it, is that I'll collect up the week's questions and try to answer them all in one blog.

In the meantime I'll go on enjoying your Facebook comments, be relieved that I have sent the manuscript of book 7, set in Ballybucklebo, to my agent, and am starting getting into book 8.

Slan Leat. Pat Taylor.

October 22, 2011

HOW IT FEELS (To be a best seller)

"Do you know what you've just done?" That's what my publisher Mister Tom Doherty asked. It was in February 2007, a Wednesday, and we were in a delightful Italian restaurant in Manhattan. His face was bereft of expression and he clutched a cell phone in one hand.

I sat back forcibly, flinched, and swallowed. Please remember I went to a boy's boarding school where such a remark by a teacher often preceded severe punishment. My hand started to tremble. Some responses are ingrained for life. We had earlier been in cheerful mid-conversation. No mean feat for me. Please understand that for an author who had just been published for the first time in his life by a major New York house such a conversation with the head of the publishing company was on a level with a chat between a novitiate priest and the big fellah in the Vatican. Then Mister Doherty broke off in mid-sentence to take a cell phone call. Right as the main course was being served—veal scallopini as I recall.

"Well do you?" There was an edge in his voice.

I shook my head and sought for the all-exonerating excuse like, "It wasn't me sir. Honestly." I looked round for support at the staff of Forge who had all worked assidiously on my An Irish Country Doctor and who had been invited by Mister Doherty to this celebratory post-publication lunch. Damn it all, they were grinning like a herd of mooncalves. Was this some rite of passage? I was beginning to feel like the sacrificial calf, the outsider to some massive in-joke.

"I'll tell you what you've done," Mister Doherty said.

No question now. It was definitely my fault that the Walls of Jehrico had come tumblin' down, the Cards had beaten the Tigers in five games in the World Series last year, and the Colts had taken the Superbowl from the Bears. I was for it.

"You, my friend," he said, and his face cracked into a grin of such massive proportions that the Cheshire Cat would have looked like a whining sniveller beside Tom Doherty, "You, my friend, have just put An Irish Country Doctor on the New York Times best seller list." He held out a hand.

I think I shook it. Only the applause from everyone else at the table muffled the 'clunk' of my jaw hitting the table top. It wasn't until, what I am sure was an acute attack of atrial fibrillation, had passed that I finally managed to mumble, "Holy Mother of God." I'm not even sure if I had the decency to say thank you to all the people there who had been in on the joke.

Tom had been waiting for the call giving him the information and everybody round that table, but me, had been waiting and hoping too.

And I was there, on the list, the little lad from Bangor Northern Ireland, who had been a doctor and had no right to be a published novelist, never mind a best seller, and would not have been without the support of very many dedicated people. Thank you all.

I spent that day glowing. I nearly caught fire when my agent Natalia Aponte came with me to my hotel to break the news to my partner, Dorothy, who hadn't been able to make the lunch. I can only hope that all those who were involved in the publication of Country Doctor could feel the same fierce pride and satisfaction as I did. They'd certainly merited it.

And they deserve to feel proud again today because Alexis Saarela from Forge has just e-mailed me. A Dublin Student Doctor, which was published last week, will debut at number 26 in the week of October 30th. And I feel as I did on that other Wedenesday four years ago. Proud, happy, yet acutely conscious of how much I owe to all the other people who have made this happen—and, oh yes, one other group without whom I'd never had made it. You. My readers. Bless you all and thank you from the bottom of my heart.