What do you think?

Rate this book

308 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1933

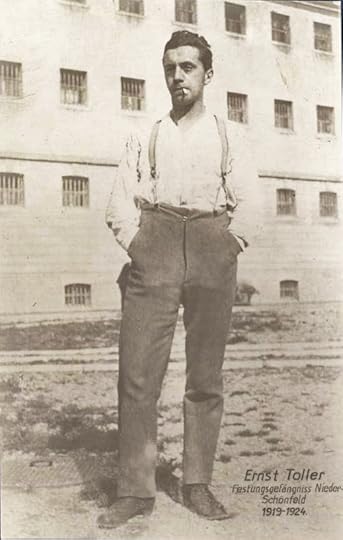

To be honest, one has to know. To be brave, one has to understand. To be just, one must not forget. When the yoke of barbarism is pressing, one must fight and not be silent. Whoever is silent in times like these betrays their human mission.Ernst Toller (1893-1939) was a German, a Jew, a student, a soldier in the first World War, a socialist, a revolutionary pacifist, a political prisoner, and a playwright — roughly in that order. About all of the roles he played you will learn something from his autobiography (published in 1933, and dated “the day of the burning of my books in Germany”). He commited suicide in 1939 at the age of 45.

When I lie in bed in the morning and look at the many pictures of the emporer, I ask myself: Does an emperor go to the bathroom? The question keeps me busy and I run to mother. “You’ll go to jail,” Mother says. So he does not go to the bathroom.

Yes, I love the money, with a bad conscience. The day is disgusting for me, the world is disgusting for me, the values that I considered yesterday eternal and immovable have become questionable, I myself am questionable.

We live in an emotional frenzy. The words Germany, Fatherland, War have magical power and when we pronounce them they don’t evaporate, they float in the air, revolve around themselves, ignite themselves and us.

One night we hear screams, as if a person suffers terrible pain, then it is quiet. “There’s someone shot to death,” we think. After an hour, the scream comes back. Now it doesn’t stop anymore. Not this night. Not the next night. Naked and wordless, the scream whimpers, we don’t know, if it comes from the throat of a German or a Frenchman. The scream lives by itself, it accuses the earth and the sky.

But I cannot forget [the war]. Four weeks, six weeks, I succeed, but suddenly it has attacked me again, I meet it everywhere, in front of the altar of Matthias Grünewald, through its pictures I see the witches cauldron in the Bois-le-Prêtre, the comrades shot to pieces and tattered, cripples meet me on my way, black veiled grief-stricken women.

No people is truly free without the freedom of their neighbors. The politicians lie to themselves and they lie to the citizens, they call their interests ideals, for these ideals, for gold, for land, for ore, for oil, for all the dead things, peoply die, starve, and despair. All over. The question of guilt of war fades before the guilt of capitalism.

A young man, on whose short, thin neck, instead of a head, a swollen pumpkin swings back and forth, gets up from his bed, shuffles to me with dangling steps, stops, bows solemnly three times, turns and goes back to his bed and repeats the ceremony every fifteen minutes. After two days I move to the hall of the melancholic.

Nothing puts more guilt on the political actor than concealment, he must tell the truth, no matter how onerous, only the truth increases strength, will, and reason.

Toller is of slight stature, he is about 1.65-1.68 m tall, has a thin, pale face, no beard, has big brown eyes, shrewd eyes, is closing his eyes when thinking, has dark, almost black wavy hair, speaks written German. His capture or information leading to his capture are subject to a reward of ten thousand marks.

We walk through the empty, dark morning streets, three soldiers marching ahead, two commissars hold me by the irons on my wrists, three soldiers follow with rifles ready to fire. In the Luitpoldstreet the clock strikes five, an old woman scurrying to the morning Mass, she turns around at the church door and sees me. “Do you have him?” she yells, lowering her eyes to the floor, slipping the rosary through her fingers in prayer, then, at the open door of the church, her crumpled mouth screeches, “Strike him dead!”

If perpetrators and non-sinners sensibly understand what they are doing and what they are refraining from doing, man would not be man’s worst enemy. The most important task of future schools is to develop the human imagination in the child, their empathy, to fight and overcome the inertia of the heart.

Pride and love are not the same, and if someone would ask me where I belong, I would answer: ‘A Jewish mother gave me birth, Germany nourished me, Europe educated me, my home is the earth, the world is my fatherland.’

They put the people off from day to day, from month to month, from year to year, until, weary of the consolations, it sought solace in desolation. The barbarism triumphs, nationalism and racial hatred and state deification blind the eyes, the senses, and the hearts. Many have warned, warned for years. That our voices are dying is our fault, our greatest guilt.

Anyone who wants to understand the collapse of 1933 must know the events of 1918 and 1919 in Germany, of which I tell here.