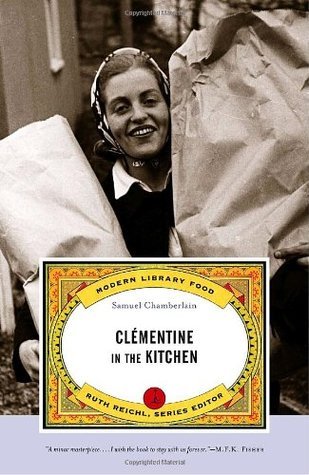

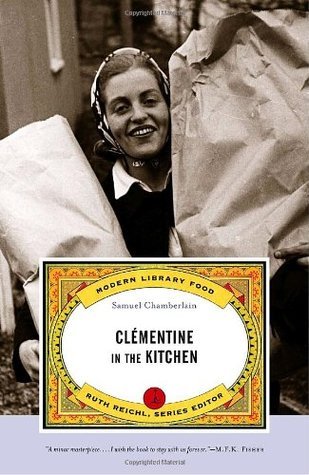

This is the Beck’s story, their family’s years of living and eating in France, but it’s aptly named, because it’s really about Clementine, their French cook, and her story is the part I really loved.

The Becks lived in France for about 12 years, for their father’s work, leaving when the build up to World War II forced them back to the States. (I think the father wrote the book originally and the adult children later revised it, but I’m not quite clear on that; the changes in names confused me.)

The early chapters focus on their French home and village and how Clementine came into their life. She opened the doors to the best produce at the local market (“too often the beauty of American ‘store’ fruit is only skin deep”) as well as the best ways to prepare that produce. (Freshness “is the answer, combined with the fact that they were probably cooked in prodigal quantities of pure butter.”)

When Mr. Beck’s company calls him home, the family immediately begins to grieve the impending departure from France, but especially from Clementine. But the littlest Beck, his father writes, has more imagination than the rest: “Why don’t you come to America with us?” he asks. And she says yes.

There are jarring lines mixed in among all the raving about truffles and beef and wine, like one about their road trip to board their ship for America, “which, in a few months, would lie at the bottom of the ocean.” They eat well when they arrive in New England, but sometimes with melancholy spirits thinking of people back in France living on rations in bomb-scarred homes.

The book is so light otherwise, these feel misplaced. But I understand the attempt to place their happy experiences within the broader historical context. (Even some of the recipes at the end are acknowledged to be for reading only, “inexcusable on moral and economic grounds” while the world groaned under agony of war.)

Clementine’s story comes into focus Stateside. Seeing her explore new tastes – her first hotdog and beer from a paper cup, for example – and find ways to bring French tastes to an American table was the best part of the book for me. The whole group had Sunday dinner at Mr. Beck’s employer’s home shortly after arriving.

Clementine “asked us afterward with a worried look if all Americans boiled their vegetables in water and then threw the water away (together with most of the taste). We looked worried, too, and admitted that most of them did, along with their English cousins.”

Beck describes how they all adjusted to an entirely new cheese plate and found comfort in fish fresh from the Atlantic. He shares many of Clementine’s recipes through the book (and more than a hundred at the end). He doesn’t make French cooking sound like the inflated affair you might sometimes imagine, but simple and flavorful and rich.

“Clementine’s cooking is loyal and simple, flattering the taste before it flatters the eye.”

My one beef with the book is how much French is left untranslated. The recipes, of course, are readable, but menus and quotes and jokes – lots of them, all throughout – are given only in French. I looked up a few, but it was too many to keep up.

This is my second read from the Modern Library Food series. (The first was Supper of the Lamb.) I’m glad these older books are being given a second chance at life.