What do you think?

Rate this book

238 pages, Hardcover

First published May 23, 2017

Dowdall is here to tell the court how Watt and Manuel came to meet. Telling stories is his job. He’s a lawyer.

Good storytelling is all about what’s left in, what’s left out and the order in which the facts are presented. Dowdall knows how to shape a narrative, calling witnesses in the right order, emphasizing the favourable through repeated questioning, skim-skim-skimming over the accused’s habit of beating his widowed mother. Dowdall is a master storyteller, better than other lawyers. He has an innate sense of narrative and he is disciplined. Dowdall can find just the right trajectory to pin his tale to and he can stop before the end. It’s the jury’s job to write the ending….

But today’s story is complex. Dowdall is in this story and he has been tricked. By sleight of hand and word Manuel manoeuvred Dowdall into breaking the law. Dowdall cannot excise himself from the story because none of the subsequent events make sense if he leaves his own misdemeanours out. He has been up half the night playing narrative chess.

BABT

BABT https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09t...

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b09t... Glasgow, 1957. Businessman William Watt wants answers about his family's murder. Small time crook Peter Manuel claims to have them. But you don't get something for nothing. Over the course of a bizarre night these unlikely drinking partners will swap stories and attempt to cut a deal with the goal of emerging from scandal with reputations, and profits, intact.

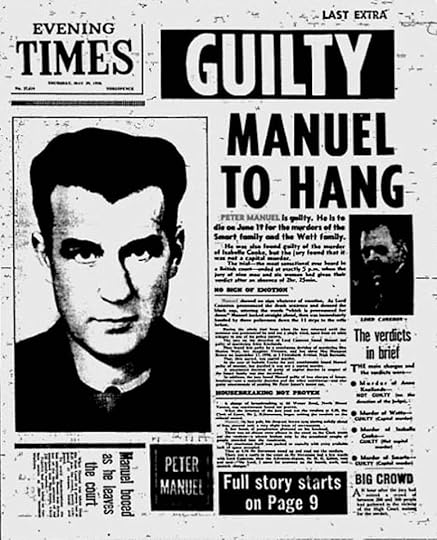

Glasgow, 1957. Businessman William Watt wants answers about his family's murder. Small time crook Peter Manuel claims to have them. But you don't get something for nothing. Over the course of a bizarre night these unlikely drinking partners will swap stories and attempt to cut a deal with the goal of emerging from scandal with reputations, and profits, intact.  2/10 Lawyer Laurence Dowdell takes the stand as Manuel is tried for eight murders

2/10 Lawyer Laurence Dowdell takes the stand as Manuel is tried for eight murders 3/10 Six months after the bizarre pub crawl, Manuel is on trial for murder

3/10 Six months after the bizarre pub crawl, Manuel is on trial for murder 4/10: William Watt takes the stand

4/10: William Watt takes the stand 5/10: Watt and Manuel struggle to stay ahead of the gangster Dandy McKay

5/10: Watt and Manuel struggle to stay ahead of the gangster Dandy McKay Manuel's victims during his killing spree

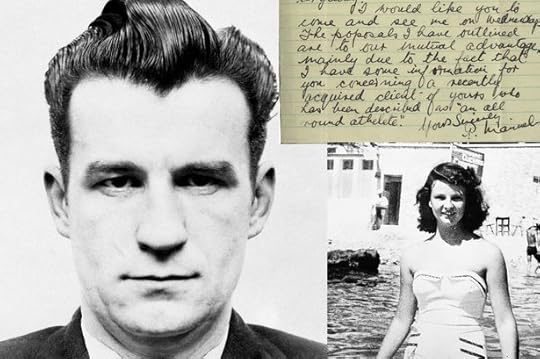

Manuel's victims during his killing spree Revealed: Taunting letters serial killer Peter Manuel wrote from his prison cell

Revealed: Taunting letters serial killer Peter Manuel wrote from his prison cell

TV: In Plain Sight is based on real life story of serial killer Peter Manuel

TV: In Plain Sight is based on real life story of serial killer Peter ManuelMary had a little cat

She used to call it Daniel

Then she found it killed six mice

And now she calls it Manuel.

Above the roofs every chimney belches black smoke. Rain drags smut down over the city like a mourning mantilla. Soon a Clean Air Act will outlaw coal-burning in town. Five square miles of the Victorian city will be ruled unfit for human habitation and torn down, redeveloped in concrete and glass and steel...Later, the black bedraggled survivors of this architectural cull will be sandblasted, their hard skin scoured off to reveal glittering yellow and burgundy sandstone. The exposed stone is porous though, it sucks in rain and splits when it freezes in the winter.

But this story is before all of that. This story happens in the old boom city, crowded, wild west, chaotic. This city is commerce unfettered. It centres around the docks and the river, and it is all function. It dresses like the Irishwomen: head to toe in black, hair covered, eyes down.

They search the car. In the glovebox they find a tin of travel sweets. The lid lifts off with a white puff of magician's smoke. Inside, translucent pink boiled sweeties are sunk into a nest of icing sugar. These are posh sweets.

Reverently, the boys take one each. They savour the flavour and this moment, when they are in a car, eating sweets with friends. In the future, when they are grown, they will all own cars because ordinary people will own cars in the future but this seems fantastical to them now. In the future they will think they remember this moment because of what happened next, how significant it was that they found Mr Smart's car, but that's not what will stay with them. A door has been opened in their experience, the sensation of being in a car with friends, the special nature of being in a car; a distinct space, the possibility of travel, with sweets. Because of this moment one of them will forever experience a boyish lift to his mood when he is in a car with his pals. Another will go on to rebuild classic cars as a hobby. The third boy will spend the rest of his life fraudulently claiming he stole his first car when he was eight, and was somehow implicated in the Smart family murders. He will die young, of the drink, believing that to be true.