What do you think?

Rate this book

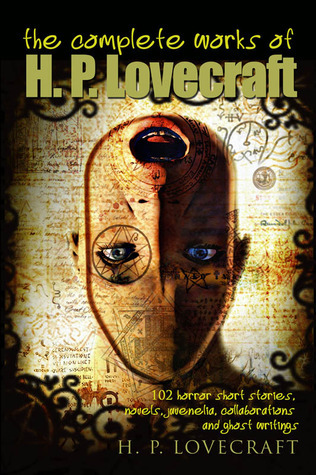

1698 pages, Kindle Edition

First published December 1, 1936

That is not dead which can eternal lie,

And with strange aeons even death may die.

HP Lovecraft is famously nativist (i.e. racist) – his way of describing non-white personages isn’t by describing the color of their skin so much as using a word like ‘mongoloid’ or ‘savage’ – AND female characters are almost non-existent in his works as anything besides window dressing. Nevertheless, if you delve into Lovecraft’s life, you can’t help but feel pathos. He was devoted to his mother, becoming near suicidal when she was committed to an asylum. He visited her and wrote her regularly, and was quite broken by her death. He struggled all his life to make ends meet and sometimes had to choose between paying for the postage to mail his latest story and feeding himself. So evil? By no means. For the other axis, nearly every Lovecraft story explores some aspect of how people respond when their perceptions of reality and cosmology are shaken. The result is, invariably, mental chaos.

The emotional strength of a HP Lovecraft story is low. They sometimes sort-of-kind-of have character arcs, but these arcs aren't compelling. His stories aren’t horrors either. There’s no sense of dread when turning the page. Rather, I would classify them as mysteries and more milieu mystery than character mystery. Any page-turning quality of a Lovecraft story arises because we’re interested in exploring the world-building and uncovering the truth of the story's strange cosmic mystery. We don’t particularly care about the fate of the protagonists, especially as most of the stories are narrated after-the-fact, anyway.

Lovecraft’s stories often remind me of how nudity was depicted in early film. It was never shown directly. The Hays code didn’t allow it. Instead, you might see a silhouette. Or a dress fall to the ground at the woman’s feet. Or there’d be a bannister in the way. Lovecraft likewise has this propensity to avoid actually describing his cosmic horrors. His characters will instead simply say, ‘I cannot describe it, for my very mind rebelled against grasping such a reality! Mouth and teeth and tentacles!’ or ‘I refuse to share this knowledge, for it will inspire madness in all who hear it.’ It is, frankly, annoying.

My copy of HP Lovecraft, The Complete Fiction is highly sturdy and well constructed. When it became temporarily possessed, I struck it with a hammer. It survived this blow intact.

HP Lovecraft was clearly a man of high intelligence. In particular, he possessed a certain arcane vocabulary that gives his stories an other-worldly aesthetic. I was delighted to discover him use not one but TWO of my favorite rare words: chiaroscuro (a word I once used in a story, which earned me a rejection note from the editor: ‘pass. too pretentious.’ bwahaha) as well as tenebrous, which I snuck into the opening for my review for PKD’s Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said. I even encountered a few words whose meaning I had to look up, which is quite the feat, given I am a connoisseur of words: fulgurite and noisome, for example. And of course there’s the classics that you’ve no doubt encountered if you’ve ever played a Cthulu game, words like eldritch or daemon or aeons or what have you, all of which serve to imbue his stories with a sense of vast cosmic mystique.

I’m probably least impressed by the humanity of HP Lovecraft’s stories. Despite his clear intelligence, I’m quite certain Lovecraft didn’t understand people. Because of this, the characters come across less as human beings with rich inner lives and more as generic passive receptors of the world. At the least, the book displays a profound lack of insight when compared to modern psychology. Today we know that ‘insanity’ isn’t a single affliction at all – it’s not even a term used in medicine anymore. Rather, what might once have been called ‘insanity’ now has a much more specific classification, such as dementia or schizophrenia, and we have some grasp of the neurological reasons behind these illnesses. Thus the madness we encounter throughout Lovecraft's stories is less a specific ailment of a specific human being than it is the general madness of our entire race as a whole.

The stories aren’t charming or magical or inspiring or anything like that. Which is fair, they’re cosmic horror. But don’t expect to come out of reading these stories energized to do good in the world or to treat your fellow human beings with greater love and kindness. Unless you think doing good in the world involves sacrificing a goat to the Elder Gods to stave off their hunger and imminent return. In which case you may well be plenty inspired.

In Lovecraftian mythos, the universe contains vast and powerful beings - Gods to some - who are beyond mortal ken. To them, we are but ants, and we draw their attention at our peril. Thus, science is in many ways foolish to so wantonly sift through the mysteries of the universe. What happens when we uncover something that is beyond our comprehension – or, worse, our control?

Much like Stephen King, HP Lovecraft set most of his stories in New England, where he lived all of his life. His knowledge of its towns, history, and geography comes through strongly and confidently.

HP Lovecraft didn’t know Sumerian, Babylonian, or Aramaic. But that didn’t stop him from making up incantations in other worldly languages. ph’nglui mglw’nafh Cthulu R’lyeh wgah’nagl fhtagn! Yi-nash Yog-Sothoth-he-lgeb-fi-throdog-Yah!

HP Lovecraft’s stories consistently use a literary technique called the Frame Narrative, which was popular at the time but is now rather antiquated. Most of HP Lovecraft’s stories actually consist of an outer framing narrative, within which the (outer) narrator encounters someone who relates the inner, usually more interesting story. The result is that each story is actually being told AFTER THE FACT. This technique makes Lovecraft’s stories more philosophical/reflective, but at the cost of drastically lowering the tension.

Dagon is to Call of Cthulhu what Magic Missiles is to Fireball. It’s not that one is superior to the other per se, but Dagon is the clear precursor, containing many of the same elements while being generally shorter and simpler. Given that, Dagon was a quicker, lighter read, but with less oomph than Call of Cthulhu. (...and yes I know Magic Missiles and Fireball aren't Warlock spells.)

This is a short and fairly simple story that, while undeniably atmospheric, is also undeniably juvenile. It all builds toward a twist that is – these days at least – a bit overdone. Whereas many of these other stories are uniquely Lovecraftian, I found this one derivative.

The Lurking Fear is a bit different than others on the list, and consequentially, I found it refreshing. For one thing, it’s less of a frame story. The narrator is the one who actually experienced the events of the story, which grants it a much better immediacy than the other stories. For another, instead of the horrors coming from outside of us, this is more about the horrors that dwell within us.

Probably my favorite spell in the book. It’s one of the better plotted, with a real sense of unfolding layers of mystery. And, rarely for Lovecraft, it actually directly addresses the greater mythos. Most of the other stories indirectly reference a world-view in which humanity is insignificant. For example, the following spell - The Case of Charles Dexter Ward - contains some necromancy, sure, but it never actually talks about where the souls of the dead reside or what that might mean for us. Call of Cthulu, however, specifically speaks of the Elder Gods and humanity’s place in a universe where such beings exist. This made it more coherent and interesting.

Not a big fan of this spell. That casting time. 104 pages! And it hits this slump in the middle where there’s a REALLY OBVIOUS plot-twist every reader will guess, but the characters are totally oblivious, and it just drags on and on and on. To the point that I began to feel a little embarrathy (this is a word I invented and am foisting upon you: it means second hand embarrassment) for Lovecraft because a huge chunk of suspense in the story hinged on this reveal.

I don’t think I’d call this Lovecraft’s most iconic story – that one must be Call of Cthulu – but I might consider it his most prototypical. Many consider it his best. You have an otherworldly visitor. In this case, it’s a comet or meteor with an, umm, let’s say a chromatic passenger (Dexter reference...). It strikes in a rural New England locale. And it’s largely told by proxy. That is, the (outer) narrator himself didn’t experience the primary events of the story. Even the (inner) narrator can only offer a first-hand account of SOME aspects. So the story is actually a frame-within-a-frame! This second-hand, third-hand approach just drains the tension from the story. That said, I had great fun because it’s dripping with horrific wonder, a uniquely Lovecraftian emotion.