When young, I was a bit mystified when I was force-fed the myths of the ancient civilizations, which in my case meant the Greeks and Romans. I thought to myself: Do these preposterous fairy tales really have anything to teach us? This was not the fault of the teachers or the education system: I was literal-minded then, and I remain so now. However, I am (slightly) better educated now than when I was 12, so I realize that the study of myth can have value, especially in the absence of abundant evidence about how people lived in ancient times. But how much better, how much more fascinating, it would be to have a simple factual description of what, for example, an average stonemason's day was like in 30 AD.

Similarly, today, I don't understand the popularity of comic book superhero genre, which falls into the populous category of activities that tens of thousands of people engage in but seem inexplicable to me, joining such diverse elements as: wearing earrings (voluntarily punch a hole in the side of your head? or even your nose? really?), washing and waxing your car on cold winter days (ok, actually, on any day at all), buying popcorn at movie theaters, buying and wearing diamonds, voting against one's own self interest, and taking interest in the lives of talentless celebrities. But I digress

Perhaps someday, like I did in the case of Greek and Roman myths, I will learn that there is some redeeming quality in today's superhero comic book genre that I was just too dense to comprehend. Until that time, however, I can take solace in the fact that, if I am not interested in superheroes in any form, I can ignore 90+% of the comic book genre, which has been re-christened “graphic novels” so that those of us insecure in our intellects can discuss them with dignity. I have a busy life, and I appreciate being off the hook in this manner.

As a matter of fact, if you read this book, Maus, and Persepolis, you seem to make a serious dent in the list of books that appear in the tiny central bubble of the Venn diagram wherein the three circles are labelled “graphic novels”, “no superheroes”, and “worthwhile”. (If you know any other books that should go in this bubble, please leave me a comment.)

Reading this book also caused me to re-examine some of Pekar's appearances on late-night television. I asked myself often: How much of this is a big put-on? Pekar was famously (at that time) irascible on the David Letterman program, but occasionally I thought I saw a character-breaking smile play across his face, as if to say “I'm not really a jerk, but I play one on TV”.

It also played that way, to my eyes, on the printed page. I asked myself: Can a person be reflective enough to produce the text of American Splendor but also clueless enough to produce the action described therein? For example, one episode relates Pekar's botched honeymoon trip from his native Cleveland to the Pacific Northwest. Pekar gets sick in an annoying (for him) but non-life threatening way: he has a condition that deprives him of his voice. He proceeds to make the honeymoon less pleasant for his new wife. Why? He's frustrated that he cannot participate in discussions that his wife seems to be enjoying perfectly well without him. Is he really so selfish that he cannot think "Well, it's her honeymoon too, I'll just sit quietly"?

I guess there are people in this world who are as childish and selfish as that, but few of those people go out later and lay their selfishness bare for the world to see as Pekar does. But it's hard to square the Harvey Pekar who behaves like a clueless jerk with the Harvey Pekar who observes his own bad behavior so unsparingly.

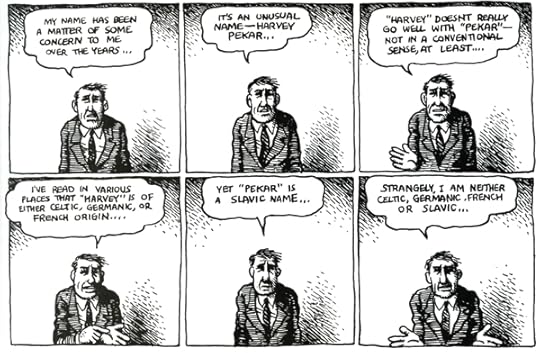

I enjoyed reading this book because, even though some pages are filled with panels of Harvey speaking directly to the reader in dense “eye dialect”*, it was still a much faster read than most conventional books I read and, as such, a welcome break from the latest 1000-page doorstop I'm now slogging through, even though it was very far from a cheerful read.

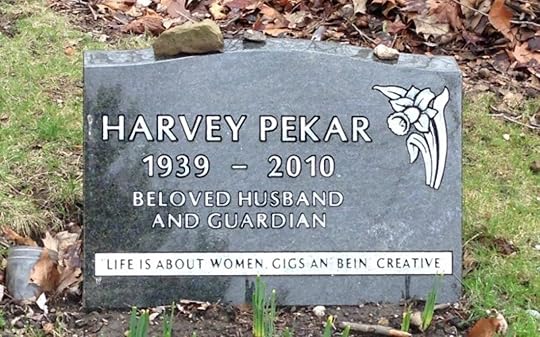

Now that Pekar has passed away, and his descriptions of life in 1970s Cleveland have become like a historical drama, it is perhaps more important to read about how normal people of that era lived because, you know, sooner or later, all of them will pass away, and it will be a lot like they never lived. Sometimes I wonder if today's electronic storage medium will go the way of the eight-track tape and the floppy disk, and if only paper medium will remain. If it does, I certainly hope this document is somehow miraculously preserved. It would be a shame if future civilizations know us only through our superheroes.

*meaning, speech rendered to portray the speaker's dialect, for example: “If y'want t'know more about that stuff, th'person t'ask is William F. Buckley or someone a'that ilk.”