Pros: wonderfully evocative of a time and place

Cons: covers only a few years in the author’s childhood

Bottom Line: A young boy’s evocative account of his eventful childhood in Hong Kong during the 1950s. Beautifully written. Highly memorable.

In 1952, 7-year-old Martin Booth and his parents leave England behind as they set sail for far-off Hong Kong where his father, a civil servant attached to the Royal Navy, is about to start a new job on a naval supply ship. The month-long journey, with seven ports of call en route, sets the tone for the family dynamics that will swirl like a tempest around young Martin.

His father, pompous and self-important, shows little affection towards either his son or his wife. Narrow-minded and fearful of the exotic, he’s the polar opposite to Martin’s mother. Poised, articulate, and with a steely streak of determination that belies her frail exterior, she stands up to her husband and imbues in her son a sense of adventure and discovery as well as respect for different cultures. She herself falls headlong in love with the colony almost as soon as she arrives, an abiding love that would last a lifetime. While she makes friends quickly and easily among both the expatriate and local residents, Martin ventures forth, with her blessing, to partake of the exotic glories of 50’s Hong Kong streetlife.

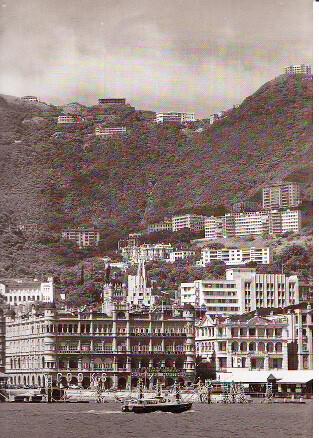

He soon learns to speak some basic Cantonese and this, together with his decision not to reject any offer of food, however peculiar, as well as his blond hair (a propitious shade of gold), endear him to the local populace. From Fourseas Hotel in Kowloon where the family first stay upon arrival, he would range as far as his feet will carry him, and have run-ins with assorted characters including the half-mad White Russian ‘Queen of Kowloon’, and even gangsters within the infamous Kowloon Walled City. When the whole family moves to an upscale apartment on the Peak, Martin would roam the hills and come to know them like his own backyard. He accompanies his parents on occasional outings to various outlying islands, where there’s no shortage of adventures for the bright young boy.

By the time they are due to return ‘home’ to England, neither Martin nor his mom is prepared to leave. What are the chances that they’ll ever return to the place they both feel they belong?

Gweilo is very much Martin’s story and it is impossible not to feel tenderly towards this young narrator. Apart from the occasional abuse and general lack of affection from his father, his mother, though loving, open-minded, and greatly beloved by him, seemed to have left him, for the most part, pretty much to his own devices. Streetwise and savvy, he roamed the streets of Kowloon and later the hills of Hong Kong on his own, with a complete autonomy that would be unthinkable nowadays.

His adventures and discoveries among the locals are many and delightful, and the reader experiences the delight almost first-hand, as the sights, sounds and smells of the growing colony are evoked in vivid, dynamic prose. The people (the locals, his parents, himself) are masterfully recreated, so that we seem to know them, on occasion, better than they do themselves. There are also flashes of humour, some arising from a young boy’s mischief, some from his very innocence.

Not only does Gweilo recount the events of a few short years in the life of Martin Booth, it also serves as an enchanting record of a Hong Kong that no longer exists. Seen through the eyes of such a young and privileged child, Hong Kong in the 50s has never looked so idyllic. Perhaps the nostalgia would be greater for those of similar background, but anyone with more than a passing interest in the Far East would find this a remarkable read.

As a memoir of a few years out of a young boy’s life, Gweilo is not only sharply-observed, it is recounted with zest, with a passion for life, with a deep and abiding curiosity that only a spunky, street-wise and adventurous 8-year-old could possess. As a re-telling of a childhood lived to the fullest, Gweilo must rank as one of the most engaging ever told.

Critics have voiced their doubts as to the veracity of what appears to be total recall of day-to-day minutiae from across several decades. The author himself has this to say:

“Once I had set out upon the task, the past began to unfold—perhaps it is better to say unravel—before me…..forever repeating itself in the recesses of my mind, like films in wartime cartoon cinemas, showing over and over again as if on an endless loop.”

With the help of a scrapbook and photographic albums compiled by his mother, he had been able to re-create the years of his childhood. If, reaching back through the years, he felt that certain details of, say, conversations, needed to be fleshed out, how could the reader find fault? And if poetic licence is taken here or there to offer a more telling, more dramatic, version of the truth, surely that is within the autobiographer’s rights. After all, how can one look back through the filter of time without gleaning some enlightenment, some perspective?

Written after he was diagnosed with a virulent form of brain tumour, and at the behest of his children who begged him to recount for them his childhood, Gweilo is part of the author’s literary legacy (which includes several novels, non-fiction works as well as children’s books). Sadly, it is also part of his epitaph— he succumbed to the cancer soon after Gweilo was completed.

I often dream of my own childhood in Hong Kong. Lately, I could almost swear that, out of the corner of my dreamsake’s eye, I catch a glimpse of a small, spunky, tow-headed boy sauntering along the alleyways, stopping for a thousand-year egg at a dai-pai-dong, exchanging pleasantries with the stall-holders, sipping a Coke through a straw in the sub-tropical heat. But when I try to stroke his fair head for luck, he’s gone like a will-o’-the-wisp.