Book: Coffee: A Global History

Author: Jonathan Morris

Publisher: Reaktion Books (17 December 2018)

Language: English

Hardcover: 176 pages

Item Weight: 408 g

Dimensions: 12.07 x 2.03 x 19.69 cm

Price: 1235/-

Coffee is an international beverage. It is grown commercially on four continents, and consumed passionately in all seven: Antarctic scientists love their coffee. There is even an Italian espresso machine on the International Space Station.

Coffee’s journey has taken it from the forests of Ethiopia to the fincas of Latin America, from Ottoman coffee houses to ‘third wave’ cafés, and from the coffee pot to the capsule machine.

This book is the first global history of coffee written by a professional historian, Jonathan Morris, a Research Professor at the University of Hertfordshire. This book expounds how the world acquired a taste for coffee, yet why coffee tastes so dissimilar all over the world.

The author has divided the book into five chapters:

1 Seed to Cup

2 Wine of Islam

3 Colonial Good

4 Industrial Product

5 Global Commodity

6 A Specialty Beverage

From the beverage’s first emergence among Sufi sects in 15th century Arabia, through to the specialty coffee consumers of 21st century Asia, this book discusses who drank coffee, why and where they drank it, how they prepared it and what it tasted like.

The book identifies the regions and ways in which coffee was grown, who worked the farms and who owned them, and how the beans were processed, traded and transported.

Coffee’s adoption across Christian Europe reflected the continent’s multifaceted affiliation with the Islamic Near East. Outbreaks of interest with the ‘Orient’ provoked interest in coffee, yet travellers writing in the early 17th century often sought to rescue the beverage from its Muslim associations by reimagining its past.

The Italian Pietro della Valle suggested coffee was the basis of nepenthe, the stimulant prepared by Helen in Homer’s Odyssey. The Englishman Sir Henry Blount claimed it was the Spartans’ black broth drunk before battles.

By locating coffee among the ancient Greeks, they successfully claimed it for European civilization, and reminded contemporaries of coffee-drinking Christians within the Ottoman borders.

There is, though, no proof that Pope Clemente VIII tasted coffee and baptized it as a Christian beverage in the 1600s, although the story’s extensive circulation suggests those with a stake in the coffee trade wished he had done so.

The author of this book perceptively analyses the businesses behind coffee – the brokers, roasters and machine manufacturers – and scrutinizes the geopolitics behind the structures linking producers to consumers.

The second-most traded commodity in the world, behind only petroleum, Coffee has become a bastion of the modern diet. Believed to have originated in Ethiopia, coffee was used in the Middle East in the 16th century to aid attentiveness.

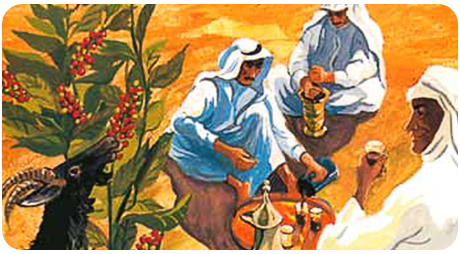

Kaldi, a lonely goat herder in 9th century Ethiopia, discovered the stimulating and bracing upshots of coffee when he saw his goats getting excited after eating some berries from a tree. Kaldi told the abbot of the local monastery about this and the abbot came up with the design of drying and boiling the berries to make a beverage.

He threw the berries into the fire, whence the instantly recognizable fragrance of what we now know as coffee glided through the night air.

The now roasted beans were raked from the embers, ground up and dissolved in hot water: so was made the world’s first cup of coffee. The abbot and his monks found that the beverage kept them awake for hours at a time – just the thing for men devoted to long hours of prayer. Word spread, and so did the hot drink, even as far afield as the Arabian Peninsula.

The history of coffee is divided into five eras:

A) Coffee first served as the ‘Wine of Islam’, cultivated on Yemen’s mountain terraces and traded among the Muslim peoples around the shores of the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea.

B) Europeans turned it into a colonial good during the 18th century, convincing serfs and slaves to plant it in places as far apart as Java and Jamaica.

C) Coffee was transformed into an industrial product in the second half of the 19th century as the rapid expansion of output in Brazil nurtured the development of a mass consumer market in the United States.

D) After the 1950s, coffee became a worldwide article of trade as Africa and Asia regained a significant share of world trade by planting Robusta, a hardier, but harsher-tasting species, used in cheaper blends and soluble products.

E) A movement to recast coffee as a ‘specialty beverage’ began as a reaction against commodification at the end of the 20th century. Its transnational success may result in the fifth era of coffee history.

Poetic as its taste may be, coffee’s history is rife with controversy and politics. It has been banned as a creator of revolutionary sedition in Arab countries and in Europe. It has been vilified as the worst health destroyer on earth and praised as the boon of mankind.

Coffee lies at the heart of the Mayan Indian’s continued subjugation in Guatemala, the democratic tradition in Costa Rica, and the taming of the Wild West in the United States.

When Idi Amin was killing his Ugandan countrymen, coffee provided almost all of his foreign exchange, and the Sandinistas launched their revolution by commandeering Somoza’s coffee plantations.

The two initial chapters of this book show that beginning as a medicinal drink for the elite, how coffee became the favoured modern stimulant of the blue-collar worker during his break, the gossip starter in middle-class kitchens, the romantic binder for wooing couples, and the sole, bitter companion of the lost soul. Coffeehouses have provided places to plan revolutions, write poetry, do business, and meet friends.

From the third chapter onwards, the author delves into how the modern coffee industry was spawned in late nineteenth-century America during the furiously capitalistic Gilded Age. At the end of the Civil War, Jabez Burns invented the first efficient industrial coffee roaster.

The railroad, telegraph, and steamship revolutionized distribution and communication, while newspapers, magazines, and lithography allowed massive advertising campaigns.

Moguls tried to corner the coffee market, while Brazilians frantically planted thousands of acres of coffee trees, only to see the price decline catastrophically.

A pattern of worldwide boom and bust commenced.

By the early 20th century, coffee had become a chief consumer product, advertised extensively throughout the world. In the 1920s and 1930s, national corporations such as Standard Brands and General Foods snapped up major brands and pushed them through radio programs.

By the 1950s, coffee was the American middle-class beverage of choice.

The book touches upon and explores broader themes as well: the significance of advertising, growth of assembly line mass production, urbanization, women’s issues, deliberation and consolidation of national markets, the rise of the supermarket, automobile, radio, television, “instant” gratification, technological innovation, multinational conglomerates, market segmentation, commodity control schemes, and just-in-time inventories.

The bean’s history also illustrates how an entire industry can lose focus, allowing upstart microroasters to reclaim quality and profits—and then how the cycle begins again, with bigger companies gobbling smaller ones in another round of concentration and merger.

The coffee industry has dominated and moulded the economy, politics, and social structure of entire countries. Two major trnds are visible here:

I) On the one hand, its mono-cultural avatar has led to the subjugation and land dispossession of indigenous peoples, the abandoning of subsistence agriculture in favour of exports, over-reliance on foreign markets, destruction of the rain forest, and environmental degradation.

II) On the other hand, coffee has provided an essential cash crop for struggling family farmers, the basis for national industrialization and modernization, a model of organic production and fair trade, and a valuable habitat for migratory birds.

The language of this book is coherent and the technique of story-telling outstanding.

And what fascinated me predominantly were the incredible images, anecdotes and loads upon loads of unanticipated facts a propos the world’s much loved bean.

Grab a copy if you choose.