Literature was for singing the beauties of life, the joy of living, the bodies of beautiful women. Without hypocrisy.

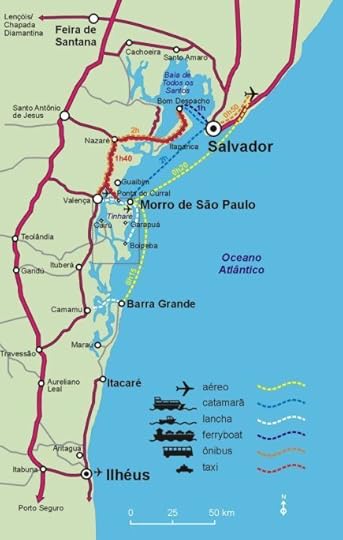

The easiest five star rating I gave in a long, long time. I laughed, I cried, I danced, I cheered for the triumphal procession through the streets of Ilheus, in the province of Bahia, as tradition and modernity struggled to reconcile the false values of small bourgeois minds with the exuberant freedom of love. What a vibrant, colourful place this Ilheus is in 1925. What a terribly cruel and deadly place this same Ilheus is at the same time. Watch them all in carnival procession, to the sound of samba drums ...

At the front, Gabriela with the banner in her hand.

Greatness is achieved by Jorge Amado not with post-modernist or magical realism tools, endless introspections or conflicted intelectuals in existential crisis. Jean Paul-Sartre describes it as the “best example of a folk novel": plain language and dramatic plotting, rooted in the author’s own childhood in Ilheus, in its customs and history.

It seems to me right now that to write an analytical review of themes and style is to be as fake and self-inflated with air as the pseudo-intellectuals of Ilhean high society. What could I even say to rival this description of the novel, written by Amado:

Adventures and misadventures of a good Brazilian (born in Syria), all in the town of Ilheus in 1925, when cacao flourished and progress reigned, with love affairs, murders, banquets, creches, divers. Stories for all tastes, a remote and glorious past of proud seigneurs and rogues, a more recent past of rich plantation owners and notorious assassins, with loneliness and sighs, desire, hatred, vengeance, with rain and sun and moonlight, inflexible laws, political maneuvers, controversy about a sandbar, with miracles, danceress, prestidigitator, and other wonders

Nacib Saad, owner of one of the two bars in town, wakes up one day to find that his old cook has finally left him. He is desperate to find a replacement, before he loses his customers to his rival. But he has to stop and listen to the momentous gossip that is spreading like wildfire through the streets: Colonel Jesuino had caught his wife Sinhazina in bed with the town’s young dentist Osmundo and had gunned down both lovers.

In Nacib’s opinion, there was nothing more enjoyable – except food and women – than to discuss the news and speculate on the latest rumours.

Gossip was the art supreme, the superlative delight, of the town.

On one thing only were they all agreed: it was a husband’s right and duty to kill his adulterous wife.

The rumour mill is churning full speed in Ilheus, with piquant details about the unclothed bodies of the lovers and even praise for the ‘macho’ behaviour of the wronged husband. The celebratory, tongue-in-cheek opening chapters describing life in Ilheus and the march of progress start to ring hollow under this assault of toxic masculinity. The Colonels who control every aspect of life in town are not military men, but self-appointed robber barons who carved vast estates from the virgin forest at gunpoint and now became rich in the export of cocoa from their plantations. Their authoritarian leader is Colonel Ramiro Bastos, old now but still ruling over Ilheus politics with an iron fist.

Life was rotten, full of hypocrisy; Ilheus was a heartless town where nothing mattered but money.

The bar Vesuvius, owned by Nacib, is the gathering place of the progressive opposition in town, about to select a young investor from Bahia as their frontman. Mundinho Falcao promises to dredge the sandbar that stops large ships from entering Ilheus harbour, facilitating exports and new taxes to invest in the town’s infrastructure.

The political conflict between old and new will be the main drive of the plot, paralleling the sentimental conflict between traditionalists and emancipated youngsters that has Nacib and his new cook Gabriela at its heart, with variations on this same theme in the lives of several other couples in town.

The sweet, spicy smell of clove emanated from her – from her hair, perhaps, or from the nape of her neck.

“Can you really cook?”

Nacib, a recent immigrant, and Gabriela, a destitute refugee from the drought that is ravaging the interior, seem made for each other once you read the way the author introduces them. Their mutual attraction is undeniable, but their love story is subject to the same unwritten laws of the Colonels: their passionate natures will lead them to an unavoidable tragedy.

He had no taste for violence. What he really liked was to eat well – good, highly seasoned dishes and a bottle of cold beer; to play backgammon or join an all-night poker game, with fervent pleas to Lady Luck lest he lose the profits he was accumulating to buy land; to maximize these profits by adulterating drinks and padding the bills of customers who held charge accounts; to go to a cabaret; and to end the night in the arms of some Risoleta. Also, to talk with his friends and to laugh.

She loved many things with all her heart: the morning sun before it got too hot; white sand and the sea; circuses, carnivals, and movies; guavas and pitanga cherries; flowers, animals, cooking, walking through the streets, talking, laughing. Above all, beautiful young men; she loved to lie with them, moaning, kissing, biting, panting, dying and coming back to life. With Mr. Nacib among others.

I think you noticed the slight difference in emphasis between the two biographies: he is carefree and a bit lecherous. She is exuberant and a bit promiscuous. What could go wrong? Well, Nacib gets possessive and jealous. His friends push him towards marriage, claiming it is the only way to control the woman. The free spirit of Gabriela is stifled by demands to be decorous, to wear shoes and proper dresses, to socialize with the town matrons and to be quiet and prim there.

“What have you done, you infidel Saracen, to my red flower, to my Gabriela? She had merry eyes, she was a song, a joy, a holiday. Why did you steal her, why did you take her away and put her behind bars? You filthy bourgeois ...”

The town of Ilheus is filled with memorable personages. Each deserves a paragraph, a mention, a context in the larger conflict. I want to concentrate on Gabriela and Nacib, so I will only say here that the voice of reason in town, most of the time, belongs to the Arab’s friend Joao Fulgencio, a true intellectual able to see and to laugh at the folly of his peers. Nacib, unfortunately, listen more often to the self-serving advice of his other young friend: Tonico Bastos, the town’s lecherous rake.

>>><<<>>><<<

I think I will stop here with the synopsis. I would rather sing the songs of Gabriela, Malvina, Gloria, of the fabled virgin Ofenisia or the murdered Sinhazinha. The author thinks the same, since each major part of the novel starts with a song dedicated to one of these women.

She had something; it was impossible to forget her. Was it her cinnamon color? The smell of cloves? Her way of laughing? How should he know? She had warmth, burning on her skin, burning inside, a fire.

Nacib is as clueless as the other men in town about the treasure he has in his hands. He thinks only about how to keep tis fire for himself exclusively. He even buys Gabriela a singing bird [its name soufre has its roots in the French word for suffering]

Superior and distant, he treated her as if he were paying her royally for her work and doing her a favor by sleeping with her.

Gabriela’s eyes turned sad. The sofre’s throat was about to burst, its song was heart-rending.

“What harm did I do?”

I don’t care how many times Jorge Amado repeats this musical theme, this opposition between the freedom of love and the prison of bourgeois hypocrisy. It’s the whole point of the novel, after all:

Life was good, one had only to live it. To warm oneself in the sun, then take a cold bath; to eat guavas and mangoes, to chew peppercorn, to walk through the streets, to sing songs, to sleep with a young man. And to dream of another.

[...] She was a daughter of the people lost in a jumble of incomprehensible talk, of unattractive sumptuousness, and of envies, vanities, and gossip that did not interest her.

It was the silliest thing: why did men suffer so much when a woman with whom they lay, lay also with another man? She couldn’t understand it.

Which brings me back to Joao Fulgencio and his common sense observations:

“I believe she has the kind of magic that causes revolutions and promotes great discoveries. There’s nothing I enjoy more than to observe Gabriela in the midst of a group of people. Do you know what she reminds me of? A fragrant rose in a bouquet of artificial flowers.”

“Eternal love does not exist. Even the strongest passion has its span of life. When its time comes, it dies, and a new love is born.”

“That’s the very reason why love is eternal,” concluded Joao Fulgencio, “because it is forever renewed. Passions die, love remains.”

I could write page after page about the actual developments in town, about the fate of each actor, about political terrorism, poverty or pretentious yet hilarious poetry reading by the eminent Doctor Argileu Palmeira – poet laureate, Parnassus , about the waging tongues of old maids, the suggestive dancing in the cabarets or the ever changing spectacle on the streets of Ilheus. All these details flesh out the grand spectacle, carnival and circus, progress and decadence, freedom and prejudice walking hand in hand.

Probably two more, brief, examples will suffice:

Malvina is a young girl about to finish high school. She tries to start a romance with the young engineer who comes to dredge the sandbar at the invitation of the progressive party. Her father, Melk Tavares, is old school:

Melk had all the rights, made all the decisions. He frequented the cabarets and brothels, spent money on women, and gambled and drank with his friends in the hotels and bars, while his wife withered away in the house, haggard and meek, compliant in every way, without a will of her own.

Malvina receives a savage beating at the hands of her father, simply for having opinions of her own. Nobody in town dares to comment, least of all her presumptive lover, who turns out to be a coward. In the end, progress is inevitable [unless you want to live in president elect Trump’s world]:

“Malvina will never beg forgiveness and she’ll probably never come back. That girl knows her own mind, and its a good one. She’ll go far – literally and figuratively.”

Gloria, she of the epic breasts proudly displayed from the window of her main street house (bought and paid by her sponsor, a married Colonel), is probably the loneliest woman in town. No man dares to speak to her in fear of the Colonel’s violent response. She sighs and she waits in vain for one that will be man enough to dare enter her bedroom.

Eventually, the town’s poet and school teacher Josue, driven by the rejection of his unrequited passion for Malvina, starts to write poetry dedicated to Gloria’s ample charms:

He exalted Gloria, a victim of society, ostracized by the community, a woman of defiled purity, undoubtedly violated by force. She was, in fact, a saint.

Gloria is, in fact, anything but saintly, but we must welcome love in any guise it decides to come knocking at the door. Joao Fulgencio deserves to have the last word on the subject, the novel’s most charming conclusion:

“Love is not to be proven or measured,” said Joao Fulgencio. “It’s like Gabriela. It exists, and that is enough.”

>>><<<>>><<<

I don’t recommend to do this before reading the novel, but if you enjoyed the visit to Ilheus, it’s a good idea to check out the 1983 movie version by Bruno Barreto. Here is a director who knew how to appreciate and film a woman’s beauty. He not only married my teenage crush Amy Irving, but he also filmed Dona Flor and her Two Husbands - Amado’s other epic novel of life and love. For Gabriela he made an inspired choice by pairing an overweight and moustachioed Marcello Mastroianni with a burning hot and costume impaired Sonia Braga. The plot is too much condensed and the support cast not quite as good as the main actors, but a musical score by the legendary Antonio Carlos Jobim is a bonus.