What do you think?

Rate this book

1200 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2009

“As I said, this book forms itself as it goes. Fields, cemeteries, newspapers, and death certificates beguile and delay me; I don’t care that I’ll never finish anything; Imperial will scour them away with its dry winds and the brooms of its five-dollar-an-hour laborers…The desert is real, as are they, but there is no such place as Imperial; and I, who don’t belong here, was never anything but a word-haunted ghost. This is my life, and I love it. Books are what we want them to be. I am where I want to be, in Paradise. Let me now commence the history of Paradise.”

”Two characteristics of the Ocean Park series, so a monograph informs us, are the hesitant-yet-defining diagonal cutaway and the half-erased boundary. Indeed, Diebenkorn writes, probably from this period, that what I enjoyed almost exclusively, was altering… Thus as his series progresses, doing the same thing over and over again, sometimes more boldly, sometimes more discreetly, subdelineation asserts itself more steadfastly in him than in its object. He enjoys the altering; he’s the William Mulholland of painting in that respect; he works and reworks his images; but his goal, unlike Mulholland’s, remains beyond expression. So, of course, does the “real” universe that we live in and feel. In a pretty essay, John Elderfield describes a typically altered Ocean Park canvas as a visibly imperfect surface that shows signs of its repair. I disagree. For me, Diebenkorn’s surface takes on an ever more “worked” texture until it approaches the infinitude of earth itself.”(pg. 687)

"What can I learn from these softly blended rectangles of color within their canvas plots? Is this what life is? Is this what Imperial is? Why and how can it make me feel anything? What were they made of, after all? marvels one collector. A monochrome flat ground and a few blobs of color... These boundaries between color-sectors in each field, I can't quite "understand" them, although when I think about a vacant lot in sight of the international fence, something hot and living but fallow in human terms, something altered most peculiarly by delineation, I can almost put my finger on what Rothko is trying to "say". (He knows the secret of Imperial.)"-pgs. 305-306

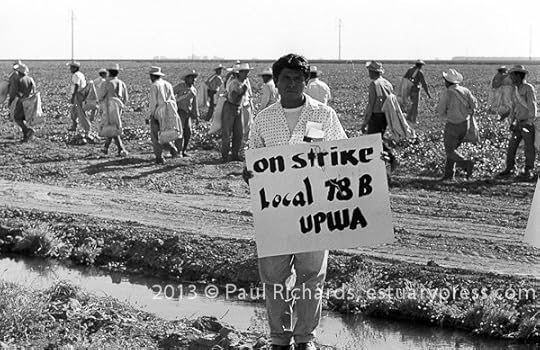

"In 1545, the Virgin of Guadalupe halted a typhus epidemic. In 1737, upon being named Patroness of Mexico, she stopped another plague. In 1775 the de Anza Expedition sang a Mass to her and adopted her among their patron saints before setting out to traverse the sands of Imperial. In 1810 a priest raised up her likeness as an icon of independence from Spain. Over the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, by whose provisions Mexico lost half her territory to the United States, the Virgin of Guadalupe presided, gazing dreamily down into space. In 1921 she withstood a time bomb. In 1966, in his "Plan de Delano" speech, César Chávez announced that at the head of their penitential cavalcade from Delano to Sacramento, a good two hundred and fifty miles, We carry LA VIRGEN DE LA GUADALUPE, because she is ours. As I write, Mexicans on both sides of the border still rely on her to help them conceive children or cure a fright. A historian of stereotypes gives the following Northside interpretation of the Virgin Mary: As a special pleader for sinners, the Virgin offered confidence in them that they could "beat the rap.""