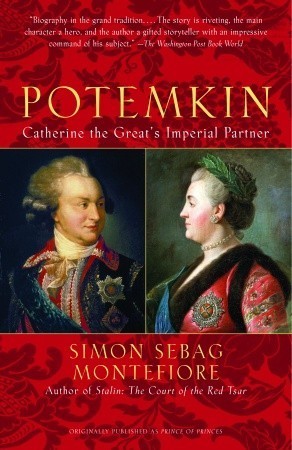

A lovely book. By chance I listened to several podcasts involving Steven Sebag Montefiore whilst reading it, and I was astonished at the towering, detailed knowledge of Russian history that he displayed. How any individual can carry so much around in his head, immediately available for use, is quite beyond me.

This book starts out as a charming and vivid mixture of history and biography, an account of a remarkable reign as viewed through the eyes and emotions of this remarkable pair – though quite quickly it becomes somehow about Potemkin. There was a moment, several hundred pages in, when I thought “my my, she didn’t seem to do all that much” – when it finally occurred to me that SSM wasn’t trying to write a history one of Russia’s golden periods, he was trying to explore how this magnificent double act functioned. And most of all, the star is Potemkin.

There’s no book of rules that insists that a “historical” account must only cover political events, or who voted for whom; and SSM goes vividly beyond that. He uses “historical” events when it suits (presumably, when the rich archives he gained access to offered juicy insights), and less so when it doesn’t. For example, he goes into blow-by-blow detail of the imperial visit to Ukraine and the battles with the Ottoman empire in 1788 (and fascinating detail it is too), but barely touches on other major events. By that stage in the book the narrative has long since morphed into a biographical-cum-diary account of Potemkin’s extraordinary doings - with Catherine as little more than the supporting act. Nothing wrong with that either – though it did leave me wondering a little why Catherine is so famous from this period and not Potemkin. In that sense perhaps the book’s title is a little misleading.

Potemkin’s court (and Catherine’s in St Petersburg) were the stuff of Arabian nights. Positively dripping with opulence and lovers and self-indulgence. Need some perfume? Well, send a courier halfway across Europe to buy some. Need to feel at home whilst waging war? Why, bring your own English garden, complete with a genuine English gardener, wherever you travel, and have the garden set up while your full orchestra, also brought along, plays selected favourites in the background. Want to impress your guests? Fill the champagne glasses (vintage, naturally) with diamonds. The evidence SSM assembles goes on and on. Oh, and I almost omitted the mistresses. No account of his derring-do could possibly be complete without the mistresses.

The life Potemkin led was astonishing, more ‘rock star’ than Mick Jagger. But at the same time, peeping round the edges of this (ostentatiously vulgar) fairy-tale, is the brutalising poverty of Russia. One element of Potemkin’s and Catherine’s personas was their generosity, handing out gifts of serfs, by the tens of thousands, to their favoured recipients. Slaves! And it struck me more than once how many times SSM used the word “barbaric” or barbarism to describe Russian army methods. True, you won’t find it on every page – but you won’t find it on any page in most accounts of European history. All in all, the book confirms to me that Russia was most certainly a Great Power under this remarkable double act; but it was scarcely a great nation, in the sense of a cultivated people taking its place alongside the other great nations of Europe. It was just very powerful, that’s all.

It certainly was by the time Potemkin finally died, at a relatively young 52 years of age. By the end the book isn’t really about the Potemkin-Catherine double act at all, it’s more about Potemkin, with Catherine as the support act. And little the worse for that, though SSM does get a bit carried away with his obvious mission to rehabilitate Potemkin’s reputation. He’s entitled to in a way, as much of the background sources he uncovers are brand new and worth recording. But it does tend to stray away from historical account and towards hagiography by that point.

In the podcast that I mentioned earlier, SSM remarked that the Kremlin had requested an early copy of the book, for the delectation of the President. It is both a tribute and simultaneously a ghastly thought that this vivid account of Potemkin’s primacy may well have influenced Putin to try to emulate him… Either way, what an important contribution.