What do you think?

Rate this book

220 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1977

…the “Twenty Days of Turin” were neither a war nor a revolution, but, as it’s claimed, “a phenomenon of collective psychosis” – with much of that definition implying an epidemic.

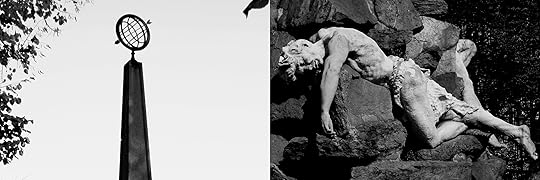

Now picture him in front of the statue of the Commendatore under a beautiful full moon. Right then, the statue starts to talk – and his Don Giovanni, instead of shitting himself, invites it straight over for dinner. When you’ve got statues that can talk and move around, it’s no laughing matter!

"La visione onirica dei bassorilievi mi aveva spaventato. Me li ero visti passare sotto gli occhi a un palmo di distanza; poi, sempre vicinissimi, si erano nascosti dentro di me in modo che non potessi più vederli ma sentirli. La loro presenza interna mi impediva di controllare cosa c'era sotto di essi; erano divenuti il coperchio di un sarcofago nel quale erano nascoste tutte le mie ricchezze; però qualcuno avrebbe potuto benissimo scavarsi un tunnel sotterraneo per venirmele a succhiare."