“This is not a book,” says Paul Gauguin as he opens his intimate journals, and I agree. But I have to say I was held enthralled by the complex and talented man who emerges from these pages of reflection, observation, personal philosophy, confession and instruction.

The preface, written by his son, quickly dispels the myth that Gauguin woke up one day, abandoned his family in France, and took off for the South Seas where he cavorted with the natives, while painting until he dropped dead at his easel of a morphine overdose, taken to lessen the pain of a profligate life. On the contrary, he left with the full agreement of his wife, the marriage having broken down. After two sojourns in Tahiti, he settled in the remoter Marquesas Islands, defined a post-Impressionist art form that captured the essence of the Pacific islands, was active in local politics, more often as a dissenter against the Church and the corrupt colonial administration, and quietly contributed to a reputation-in-absentia back home in Europe.

This journal appears to have been written during his final years in the Marquesas, when he was trying to assemble the pieces of learning from his nomadic life, for the recollections of his early life in Europe (and childhood in Peru) are sketchier than those recorded on the islands. Yet, he spends some time detailing his relationship with Van Gogh and the last days that he spent in the company of this other tortured genius who committed suicide while they were sharing rooms in France. He also spends a few pages on his relationship with Degas who was a mentor.

Experts and academics had difficulty boxing Gauguin into a particular school of art—was he an Impressionist like his colleagues, a post-Impressionist, or a Primitivist—for he lived at a time when art was bursting out of traditional boundaries into something yet undefined. Gauguin resisted categorization: “The difference between a painter and a mason is that the mason builds to a plan, a frame, a model. The painter paints from memory, sensation, and intelligence, and his soul will triumph over the eye of the amateur.”

His quotes of personal philosophy characterize the man best, and I’d like to quote a few gems from this book :

1) Precision often destroys a dream.

2) Take care not to step on the foot of a learned idiot. His bile is incurable.

3) No one is good, no one is evil. Everyone is both.

4) Toil endlessly. Otherwise what would life be worth?

5) The tenderness of intelligent hearts are not easily seen.

6) The lower genius sinks, the higher talent rises.

Yet, despite these incisive observations, he claims that the subterfuges of language and the artifice of style are not suited for his barbaric heart, although he does not disdain such. “There are savages who like to cloth themselves now and then.”

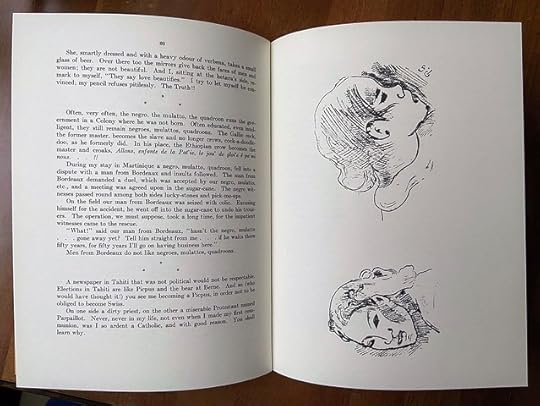

He rambles on in this book, just like he did in life: taking a walk through an art gallery and critiquing the paintings therein, discussing their respective styles; reliving the storm that flooded his house upon arrival in the Marquesas; talking about the process of making Japanese Cloisonné, discussing the finer points of fencing and boxing; he talks at length of his dislike of Denmark, from the habits and customs of the Danes to their localization of art: “Venuses turned Protestant, modestly draped in damp linen”; he recounts his youthful voyage as a seaman to Rio De Janeiro where he had a series of sexual escapades with older women; he laments for the Marquesan islanders ravaged by western diseases, corrupted by colonial officials, lacking efficient services, burdened by crushing taxes, and helpless against the proliferation of prostitution.

And although he was unconsciously building this aura and reputation that was to follow him to this day, his last days were spent in debt, in pain, and forgotten at the far reaches of the French colonial empire.

“This is not a book,” he maintains after this circulatory journey through his intimate journal. And then stubbornly defends what he has written by concluding, “It is my right to write, and the critics cannot prevent it.”