What do you think?

Rate this book

192 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1879

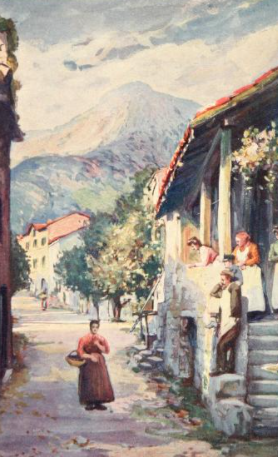

"For my part, I travel not to go anywhere, but to go. I travel for travel’s sake. The great affair is to move; to feel the needs and hitches of our life more nearly; to come down off this featherbed of civilisation, and find the globe granite underfoot and strewn with cutting flints.... To hold a pack upon a pack-saddle against a gale out of the freezing north is no high industry, but it is one that serves to occupy and compose the mind.”

They told me when I left, and I was ready to believe it, that before a few days I should come to love Modestine like a dog. Three days had passed, we had shared some misadventures, and my heart was still as cold as a potato towards my beast of burden. She was pretty enough to look at; but then she had given proof of dead stupidity