What do you think?

Rate this book

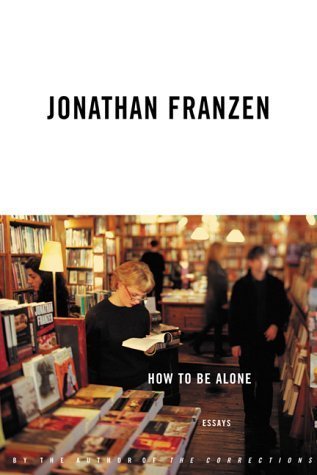

278 pages, Paperback

First published October 1, 2002

That a distrust or an outright hatred of what we now call “literature” has always been a mark of social visionaries, whether Plato or Stalin or today’s freemarket technocrats, can lead us to think that literature has a function, beyond entertainment, as a form of social opposition.

These lines are redolent with depression and the sense of estrangement from humanity that depression fosters. Nothing aggravates this estrangement more than a juggernaut of hipness such as television has created and the digital revolution’s marketers are exploiting.

When I talk to admirers of Winfrey, I’ll experience a glow of gratitude and good will and agree that it’s wonderful to see television expanding the audience for books. When I talk to detractors of Winfrey, I’ll experience the bodily discomfort I felt when we were turning my father’s oak tree into schmaltz, and I’ll complain about the Book Club logo. I’ll get in trouble for this. I’ll achieve unexpected sympathy for Dan Quayle when, in a moment of exhaustion in Oregon, I conflate “high modern” and “art fiction” and use the term “high art” to describe the importance of Proust and Kafka and Faulkner to my writing. I’ll get in trouble for this, too. Winfrey will disinvite me from her show because I seem “conflicted.” I’ll be reviled from coast to coast by outraged populists. I’ll be called a “motherfucker” by an anonymous source in New York magazine, a “pompous prick” in Newsweek, an “ego-blinded snob” in the Boston Globe, and a “spoiled, whiny little brat” in the Chicago Tribune. I’ll consider the possibility, and to some extent believe, that I am all of these things.He isn't all of those things, dear reader (or even most of of them most of the time, &c). He is, like us, just a fallible human being who loves books, whose little life, as a youthful outsider, was rescued by literature, and who fears for its future more than for his own.

I love novels as much as Birkets does, and I, too, have felt rescued by them. I’m moved by his pleading, as a lobbyist in the cause of literature, for the intellectual subsidy of his client. But novelists want their work to be enjoyed, not taken as medicine.