What do you think?

Rate this book

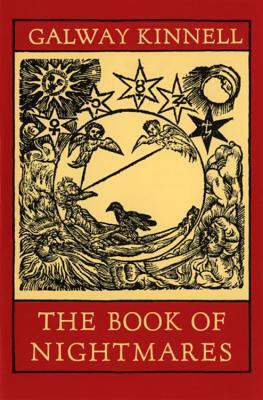

88 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1971

“No matter, now, whom it was built for, it keeps its flames, it warms everyone who might wander into its radiance, a tree, a lost animal, the stones, because in the dying world it was set burning.”