What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2012

The piano is a universe, Massimo, he said, it is not a world, it is not a country, and it is certainly not a drawing room, it is a universe. The piano is not an instrument for young ladies, Massimo, he said, it is an instrument for gorillas. Only a gorilla has the strength to attack a piano as it should be attacked, he said, only a gorilla has the uninhibited energy to challenge the piano as it should be challenged. Liszt was a gorilla of the piano, he said, Scriabin was a gorilla of the piano. Rachmaninov was a gorilla of the piano. But the first and greatest gorilla of the piano was Beethoven.(…) Even when you get a refined musician like Benjamin Britten, he said, he cannot escape the terrible English sentimentality when he composes, though that is blessedly absent when he plays the piano, which he does to very good effect. He is not a gorilla of the piano, but he is, let us say, a gazelle of the piano, and that is no mean thing.

My nose is handsomer and more distinguished than most of theirs, he said. It is a Sicilian nose. An aristocratic nose.Josipovici created a wholly likable misanthrope, not least thanks to these occasional nonsensical or humorous moments. Here’s how he makes a witty allusion to the typically diverse nationalities of chamber ensemble members:

– Tell me about the quartet. […] They spoke Italian?Above all, however, there is the originality of Pavone/Scelsi’s mind as an avant-garde composer and inspiring visionary.

– Yes. They all spoke Italian. Except Mr Halliday. Mr Pavone spoke to them in French. Sometimes Mr Stankevitch and Mr van Buren spoke to each other in German. Or perhaps it was Czech or Dutch. And when they were all together they spoke in English.

Each sound is a sphere, he said. It is a sphere, Massimo, and every sphere has a centre. The centre of the sound is the heart of the sound. One must always strive to reach the heart of the sound, he said. If one can reach that one is a true musician. Otherwise one is an artisan.

When the composer understands that eternity and the moment are one and the same thing he is on his way to becoming a real composer, he said.

The root of the word inspiration is breath, he said, and all music is made of breath.

Wonder, Massimo, he said, without wonder life is nothing. Without wonder we are ants. Everything about us is a cause for wonder, Massimo, he said. A woman. Her elbow. Her wrist. A tree. Its leaves. Its smell. A sound. A memory. And the person who can help us to wonder is the artist. That is why the artist is sacred.

“Non sminuite il senso di ciò che non comprendete.”

G. Scelsi, Octologo

"Do not belittle the meaning of what you do not understand."

G. Scelsi, Octologo

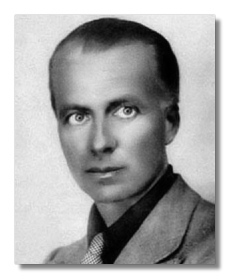

Infinity is a novel, and though Tancredo Pavone says many things with which I agree, he also says much I disagree with or find ridiculous. He is based on the wonderful reclusive Italian composer, Giacinto Scelsi (1905-1988), whose pronouncements about everything from rhythm in music to beautiful women and the future of civilisation are a curious mixture of profundity and bullshit. In fact it was this mixture I found so appealing and tried to mimic.