What do you think?

Rate this book

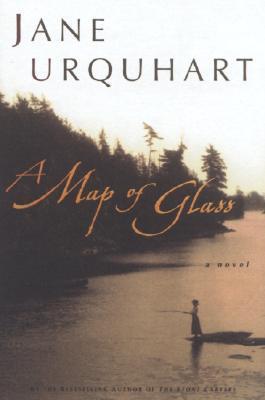

371 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2005

The whole unnamed world is so beautiful to him now that he is aware he has left behind vast, unremembered territories, certain faces, and a full orchestra of sounds that he has loved.He is walking, as one of the other characters later remarks, toward his past. The book that follows will be the slow uncovering of that past, not only as it applies to Andrew and his forebears, but by extension to the whole of Canada, its natural resources, and the way of life that squandered then vanished with them.