The Endurance is a short, quickly-paced book about Ernest Shackleton’s failed expedition to cross the Antarctic. The book was originally intended as a companion volume to the American Museum of Natural History’s 2011-12 exhibition, but can be read and enjoyed on its own.

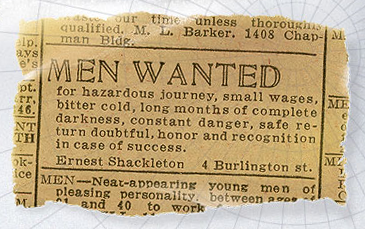

The 1914 Trans-Antarctic Expedition, lead and organized by Ernest Shackleton, has captivated scholars and adventurers alike. Even now, a century on, it remains one of the greatest stories of human survival. The journey of the 27-man crew is canonical and especially unusual for its extensive crew documentation: virtually all the members maintained detailed journals, and a filmmaker-photographer accompanied the expedition with the intention of making a documentary. Numerous books have been written about the expedition, including Shackleton’s own South, and Edward Lansing’s Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage.

Caroline Alexander is a deft storyteller, efficiently and seamlessly merging excerpts from crew members’ diaries with photographs and independent research. She contextualizes the events of the expedition against the world arena, providing a rudimentary social and political framework upon which to build the story. She had access to sources previously unavailable to other researchers, and skillfully unifies diary entries and independent research. The result is a comprehensive, thoughtful, and thorough recollection of the expedition. With unexpected intimacy, Alexander reconstructs both the physical voyage and the burgeoning relationships between the men. She has an acute sense for the social dynamics on the ship, and is skilled in her candid nuanced portrayals of the individual men.

The story is, too, one of profound individual and shared loss: the destruction of the ship, Endurance, the abandonment of the intended goal, and the elimination of the final shreds of human comfort. In the spare, unforgiving Antarctic landscape, every minute comfort is integral morale – and the loss of any part is devastating. Dogs were brought on the expedition, with the intention of using them for sledging across the ice floes and tundra. After the expedition’s original intent is abandoned, the dogs are no longer needed (and become a burden: consuming valuable resources). Ultimately, the necessary action is to cull the sled dogs: in the crewmen’s journals, this event is detailed as one of the most difficult tasks ever undertaken. Similarly, Harry McNish’s beloved cat, Mrs. Chippy (brought onboard as an unofficial mascot and ship-pet), is also killed: the personal loss suffered never quite heals and alienates McNish from the other crew members.

With these events, especially, the remaining artifice of humanity in the Antarctic is destroyed: the affection and caretaking for the crew’s animals. The elimination of the dogs and cat is one of the most final and damning demonstrations of nature’s detached, dispassionate brutality in the expedition. And yet, it is a testament to the mental and physical fortitude of the men that despite the setbacks, losses, and constant dangers, they remain generally good-humored and civil, publicly and privately. The characteristic English stoicism is present as the men to recount their brief descents in madness and near-annihilation in the elements: diary entries are terse (though often dryly humorous) and even clinical.

The chronology is also notable: Shackleton and his men left in 1914 and were outside radio contact for the majority of World War I. As the War progressed, the public perception of heroism, too, shifted dramatically. At the outset, the individual, affluent English explorers gleaned tremendous public attention and support; the advent of World War I re-defined heroism as military members, serving as a force of benevolence overseas. The wealth and aristocracy that had cultivated Shackleton’s celebrity, then, became another relic of the Romanticized Colonial past – eroded by the wartime effort and displaced by new icons and values.

In many ways, the Shackleton expedition marked the end of the great Romantic period of English exploration (resurrected dramatically, if briefly, by Tenzing Norgay and Sir Edmund Hilary in their ascent of Everest). The mechanized destruction of World War I, its revolt against the dreamy, Romantic ambitions of the late 19th century, left little space for the decadence of financed exploration. Alexander notes the difficulty Shackleton had in procuring rescue vessels for his men, in part due to the Great War. The British government provided funding in 1914, but (by 1917) was consumed with the war effort and unable (and unwilling) to devote additional resources the expedition: the PR value of rescuing the men didn't offset the manpower and cost necessary for such action. National attentions were turned elsewhere: to faltering economies, the war effort, post-war reconstruction.

After dispersing from the Falkland Islands , most crew members immediately entered military or civilian service to their respective countries. The book’s final act is devoted to the post-expedition lives of the crewmembers, ranging from abject poverty to business ownership (with one crewmember, not warmly viewed by his cohorts, finding profession as a spy). The eclectic crew, unsurprisingly, went on to equally disparate lives.

As an aside: I made the mistake of reading The Endurance on Kindle: the text is interspersed with photographs (taken by crewmember Frank Hurley), the beauty and detail of which is lost on the Paperwhite’s screen. This is certainly a volume to read in physical form, as the included photographs add tremendously to the work’s depth and emotion. Others have remarked on the impeccable print quality of the physical book, and I strongly recommend seeking it out in lieu of an electronic copy.