What do you think?

Rate this book

729 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2002

2015 Reboot as I didn't bookmark where I was up to the last time this was picked up.

2015 Reboot as I didn't bookmark where I was up to the last time this was picked up. The Bronze Horseman by Pushkin is here

The Bronze Horseman by Pushkin is hereStravinsky emerged and, standing at the top of the landing stairs, bowed down low in the Russian tradition. It was a gesture from another age, just as Stravinsky's sunglasses, which now protected him from the television lights, symbolized another kind of life in Hollywood.

Such was the challenge that confronted Russia’s poets at the beginning of the nineteenth century: to create a literary language that was rooted in the spoken language of society. The essential problem was that there were no terms in Russian for the sort of thoughts and feelings that constitute the writer’s lexicon. Basic literary concepts, most of them to do with the private world of the individual, had never been developed in the Russian tongue: ‘gesture’, ‘sympathy’, ‘privacy’, ‘impulsion’ and ‘imagination’ - none could be expressed without the use of French. Moreover, since virtually the whole material culture of society had been imported from the West, there were, as Pushkin commented, no Russian words for basic things:

But pantaloons, gilet, and frock —

These words are hardly Russian stock.

‘Modern mass culture’, Tarkovsky wrote, ‘is crippling people's souls, it is erecting barriers between man and the crucial questions of his existence, his consciousness of himself as a spiritual being.’ This spiritual consciousness, he believed, was the contribution Russia might give to the West - an idea embodied in the last iconic image of his film Nostalgia (1983), in which a Russian peasant house is portrayed inside a ruined Italian cathedral.Modern mass culture in the Brezhnev era. Imagine what he would have made of the mobile phone era!

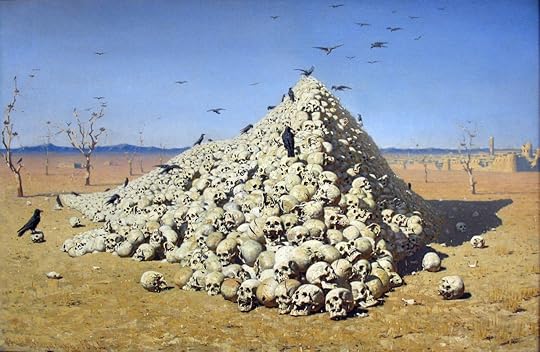

In the terrible years of the Yezhov terror, I spent seventeen months in the prison lines of Leningrad. Once, someone 'recognized' me. Then a woman with bluish lips standing behind me, who, of course, had never heard me called by name before, woke up from the stupor to which everyone had succumbed and whispered in my ear (everyone spoke in whispers there):

'Can you describe this?'

And I answered, 'Yes I can.'

Then, something that looked like a smile passed over what had once been her face.