What do you think?

Rate this book

576 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1987

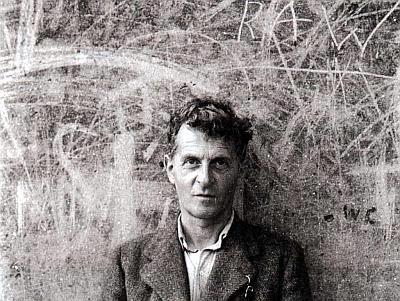

This is a work of fiction: it is not history, philosophy or biography, though it may seem at times to trespass on those domains. Although the book follows the basic outlines of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s life and character, it makes no attempt at a faithful or congruent portrayal, even if such were possible – or desirable for the aims of fiction.He goes on to mention a few specific items of historic fact which he bent in his work, for example the arrival of Wittgenstein in Cambridge has been moved from 1911 to 1912, and he has given Wittgenstein two sisters rather than the three he actually had.

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.In this astounding first novel about the philosopher Ludwig Wittengenstein, published in 1987, Bruce Duffy manages to include an impressive number of the things on earth (enough to make WW1 and the Holocaust appear mainly as interludes), and quite a few of those in heaven also. But writing about a man who, for all his stature as a philosopher, was also a very private individual, Duffy is forced to do quite a bit of dreaming himself. After descending on Cambridge like a thunderbolt in 1911 and almost immediately challenging the basic philosophical tenets of his mentor, Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein returned to Austria to fight on the Russian front in the First World War, after which he gave away his vast fortune and worked for many years in seclusion as a village schoolmaster. This so-called "lost period" before the philosopher returned to Cambridge in 1929 (to take in short order his doctorate, a fellowship, and the university chair) is only one area where Duffy has had to guess. But he guesses very engagingly, inventing for example a fellow veteran called Max as a companion for the philosopher, a "natural man" who acts impulsively upon his beliefs and desires and serves as a foil to the late-Tolstoyan cast to his life at that time. This is also one of the many ways that Duffy touches upon Wittgenstein's probable sexuality, still a sensitive subject at the time he was writing.

No, Wittgenstein did not have to go as far as the firs that day. The point was to go just far enough to singe himself without tasting, to smudge his nose against the window of that world.What a superb phrase!