This book and assignment were completed for a class; hwoever that does not make my thoughts and feelings on the subject any less truthful (though perhaps more subdued). Also, I was working with the large print edition by Thorndike Press.

Jocelyn Fleming became the Duchess of Eaton when she married the elderly and sickly Edward Fleming, sixth Duke of Eaton. Upon his death, Edward left her with quite a fortune and her virginity intact (do not worry, Edward and Jocelyn cared for each other, though it may have been in more of a paternal manner). Despite the fact that her state of virginity would later hinder her ability to remarry, Jocelyn had other worries to contend with: Elliot “Longfellow” Steele had been hired by Edward’s greedy relatives to kill her. Having left her home in England, traveling around the world in order to escape the attempts on her life, Jocelyn has found herself in the American West and with a budding desire to remarry three years later. As luck would have it, during one such attempt on her life, Jocelyn was saved by the handsome half-breed, White “Colt” Thunder. Born from a Native American mother and white father, Colt was a sharpshooter, familiar with the land, and a conveniently attractive means of dispensing with her virginity (the ol’ “three birds with one stone” tactic). Having hired Colt as her guide, Jocelyn traveled across the Wild West, from Arizona to Wyoming, escaping more attempts on her life, finding adventure, and falling in love along the way.

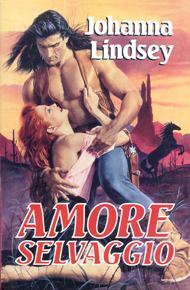

Though Savage Thunder, by Johanna Lindsey, was able to evoke feelings of contentment, love, excitement, and passion, the novel’s continuous use of the innocent virgin trope throughout the novel is problematic in the social misconceptions it has perpetuated.

The first social misconception covered in this review is the novel’s treatment of historical events regarding imperialism. Jocelyn's British nationality was a tool used to explain her ability to get past the judgmental American mentality regarding Colt, without having to be related to him (seriously, the only characters who do not regard him with contempt are his family members. Even the awe his skills garnered was contemptuous):

“‘That mean your English?’ ‘Yes.’ She smiled at the way he had of chopping up the mother tongue, though she could understand him perfectly, and rather liked the slow drawl to his words. ‘I assume you are an American.’ He knew the word, but he’d never heard anyone use it before. Folks usually associated themselves with the state or territory they were from, not the country. And now he recognized her accent too. Though he’d never heard a woman speak with those cultured tones before, he’d met several Englishmen touring the West. But her nationality explained why she hadn’t minded touching him” (80).

The use of her nationality as a plot device is evident when evaluating the impossibility of Jocelyn being unfamiliar with the concept of discrimination; Britain has been known historically as a great Empire that wielded an imperial power over half the world. Even giving the character the benefit of the doubt (perhaps she did not get great scores in History), Jocelyn had traveled the world, including the North African country of Morocco where she had been pursued by a sheikh, leading readers to doubt her ability to remain innocent of such a pervading globally-impacting social issue (49). (Like, come on! I know the novel is historical fiction, but did it have to be so... fictional?) The blatant disregard of Britain’s imperial history promotes the social misconception that the atrocities empires had evoked upon colonies was immaterial. (I mean, if you cannot even remember it, it cannot be that terrible, right? Wrong!)

It is this same (annoying) innocence that impacted Jocelyn’s regard on race. Though Jocelyn claimed to be without racial prejudice, she still regarded Colt’s religious practice of the Sun Dance as being “so barbaric,” and when she has her “first sight of genuine American Indians…not of the tame variety,” her initial reaction towards them was not as warm as it was to Colt (400, 216). Readers are then introduced to the social misconception: race is an exotic element to be desired. This is exemplified in Jocelyn of Colt:

“too handsome by half, had been her first impression, followed now by strength, which she had felt firsthand, darkness, and strangeness in that order. Hair as black as pitch, perfectly straight, and falling well past incredibly wide shoulders. Skin darkly bronze with lean, hawkish features, a nose straight and chiseled, deep-set eyes under low, slashing brows, lips well drawn, and a firm square jaw. A long sinewy body finished the picture, encased in a strange animal-skin jacket with long fringes attached, and knee-high boots without heels, of the same soft tan skin and also with fringes” (75-76).

His “strangeness” is a foreign, otherness, as well as, an exotic commodity that seduced Jocelyn (in much of a “love-(lust)-at-first-sight” fashion)--what repelled others, attracted her. Having loved him before even knowing him--his history, his personality, his likes and dislikes--Jocelyn's innocently lustful reaction, presented race as an individual’s defining quality and illustrated the novel’s sexualization and sensualization of the matter.

Though Jocelyn is not overly presented as fragile, a third misconception furthered in the novel is female weakness. Jocelyn herself claimed to be “rather good at sailing, archery, tennis, and bicycling,” and readers are given a glimpse of her ability with a rifle and horse in the scene where “she fired off two shots that hit the dust at the lion’s feet and sent it racing off into the distance. The noise also scattered a half-dozen nearby jackrabbits, grouse, and even a wild turkey that had previously gone unnoticed. Three more shots in quick succession ended the flight of two of the rabbits and the turkey” (428, 199-200). Despite the fact that she was extremely capable, she still needed to be saved and never used any of her skills to help herself (I kept expecting her to ride out of danger or shoot her enemies, alas she remained a damsel in distress). In fact, the saloon scene, where Jocelyn dressed as a young boy, highlights how the heroine is both courageous and innocence; though she gathered the courage to hold a gun to Ramsay Pratt (the monster readers meet in a gruesome scene in the beginning of the book; he is horrible) and had steadied her resolve to shoot him, she shot a blank (yea, her gun ends up being unloaded, I know) (451-453). It’s Colt who killed Ramsay, thereby saving the day and Jocelyn’s innocence. Jocelyn’s capability and skills are used only in an effort to show off to and impress Colt, are nothing more than a resource to distinguish her from other women (because it is really unique and desirable when every heroine is the same). This furthers the social misconceptions that women should be weak and dependent, (wait for that white knight, girls, I’m sure he’ll come around sometime) rather than urging them to save themselves.

The final misconception I will address is the misconception that love excuses any action. Jocelyn deems Colt a perfect candidate to lose her virginity to because he was 1.) body-tingling attractive and 2.) an American half-breed, meaning he had no social connection with anyone who would know Edward, thereby saving her late husband’s reputation (another social misconception this is now happily put to rest). Colt, having had a previous romantic relationship with a white female that left him scarred (she was a complete witch-with-a-b—trust me on this, I did not fault him one bit), avoided all interactions with Jocelyn, at first, and, as a result, was rather rude to her. Naively determined, Jocelyn disregarded his feelings on the matter and trapped him into being her guide, thereby forcing him to be in her company so that she may act out her desires. When discussing the matter with her confidante, Vanessa, Jocelyn aptly labeled the situation as it was:

“‘He was practically raped—’ ‘What?’ Jocelyn waved a hand dismissively. ‘The principle was the same. He had to be forced, didn’t he? Seduced? Made to lose control so his baser instincts would take over and he would be powerless to resist? You seem to forget he didn’t want anything to do with me, that I did the pursing, not him’” (283-284).

Jocelyn shamelessly and selfishly used Colt without regard to his feelings on the matter, yet it is all excused away in the end because readers discover that she did it for love, that her lust and desire for him was not motivated simply by physical needs but also emotional needs as well, that it is simply her innocent naivety in the matters of sex and love that had her confusing the two in the beginning. (Aw, how sweet. Actually, not really.)

Before your heart bleeds for Colt, let me say he was not without fault either. In fact, during the first few sexual encounters with her, he was a beast (of the fairytale kind of course). When he kissed her, he was “more brutal than she had counted on,” and the next day her “lips felt puffy and sore” because “he had actually hurt her” (170, 177). Again, the idea that his actions were excusable because of “troo luv” (*fluttering eyelashes*) is ridiculous and unacceptable. If a guy were to treat you like that on the first date, ladies, end the date right then and there and leave him without a backwards glance of regret. That is not love; that is abuse. Anyone who tries to paint it otherwise is simply perpetuating rape culture.

However, I am not claiming that Lindsey was advocating rape. (Not at all! And that is not sarcasm.) Rather, it is the confines of the innocent maiden trope that has forced such controversial and dubiously consensual scenes. Colt, the hero, must play the part of the forceful seducer, tempting the innocent with the fruit of carnal knowledge. This is best exemplified in the scene where Colt and Jocelyn rode horseback together: “When she didn’t obey him, his fingers delved more deeply inside of her. She gave a tiny moan, of protest or pleasure, he wasn’t sure which. Neither was she, but finally her hands fell away from her clothes to grip his thighs. ‘That’s better,’ he bent to whisper by her ear. ‘Do you still want me to remove my hand?’ She wouldn’t answer. ‘You like it, didn’t you?’ She still wouldn’t answer. But her back arched, her head reared back, and her fingers were now kneading his thighs in a desperate manner” (417). (I’ll allow you the pleasure of finishing the scene when you come across it yourself.) Colt must awaken her desires without compromising her innocence, so that Jocelyn may continue playing the part of the innocent.

I enjoyed the novel, yet the typical romantic tropes, especially the ones revolving around the innocent maiden, used are troubling. A romantic novel in which the heroine is not a perpetuation of this trope? Now that’s my kind of novel!