What do you think?

Rate this book

263 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1990

When I was a small girl at the St. Francis Boarding School, the Catholic sisters would take a buggy whip to us for what they called "disobedience. " At age ten I could drink and hold a pint of whiskey. At age twelve the nuns beat me for "being too free with my body." All I had been doing was holding hands with a boy. At age fifteen I was raped. If you plan to be born, make sure you are born white and male.

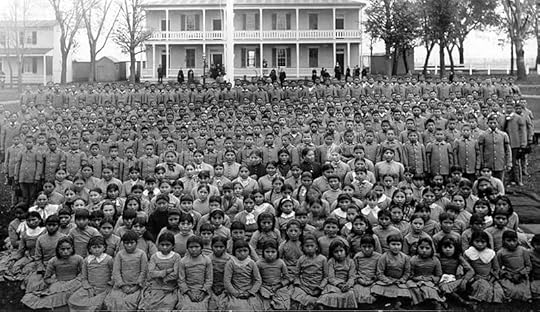

It is almost impossible to explain to a sympathetic white person what a typical old Indian boarding school was like; how it affected the Indian child suddenly dumped into it like a small creature from another world, helpless, defenseless, bewildered, trying desperately and instinctively to survive and sometimes not surviving at all. I think such children were like the victims of Nazi concentration camps trying to tell average, middle-class Americans what their experience had been like…

…The kids were taken away from their villages and pueblos, in their blankets and moccasins, kept completely isolated from their families-sometimes for as long as ten years-suddenly coming back, their short hair slick with pomade, their necks raw from stiff, high collars, their thick jackets always short in the sleeves and pinching under the arms, their tight patent leather shoes giving them corns, the girls in starched white blouses and clumsy, high-buttoned boots-caricatures of white people. When they found out-and they found out quickly-that they were neither wanted by whites nor by Indians, they got good and drunk, many of them staying drunk for the rest of their lives.

People talk about the "Indian drinking problem, " but we say that it is a white problem. White men invented whiskey and brought it to America. They manufacture, advertise, and sell it to us. They make the profit on it and cause the conditions that make Indians drink in the first place.

I have often thought that given an extreme situation, I'd have it in me to kill, if that was the only way. I think if one gets into an "either me or you" situation, that feeling is instinctive. The average white person seldom gets into such a corner, but that corner is where the Indian lives, whether he wants to or not.

The thing to keep in mind is that laws are framed by those who happen to be in power and for the purpose of keeping them in power. That goes for the U. S. A. as well as for Russia or any other country in the world .

It was only two miles or so from where Grandfather Fool Bull stood that almost three hundred Sioux men, women, and children were slaughtered. Later grandpa saw the bodies of the slain, all frozen in ghostly attitudes , thrown into a ditch like dogs. And he saw a tiny baby sucking at his dead mother's breast.

"Our most sacred altar is this hemisphere, this earth we're standing on, this land we're defending. It is our holy place, our green carpet. Our night light is the moon and our director, our Great Spirit, is the sun."

"Finally, on February 27 , 1973 , we stood on the hill where the fate of the old Sioux Nation, Sitting Bull's and Crazy Horse's nation, had been decided, and where we, ourselves, came face to face with our fate. We stood silently, some of uswrapped in our blankets, separated by our personal thoughts and feelings, and yet united, shivering a little with excitement and the chill of a fading winter. You could almost hear our heartbeats.

…Altogether we had twenty-six firearms-not much compared to what the other side would bring up against us. None of us had any illusions that we could take over Wounded Knee unopposed. Our message to the government was: "Come and discuss our demands or kill us!" Somebody called someone on the outside from a telephone inside the trading post. I could hear him yelling proudly again and again, "We hold the Knee!"

He could not understand why the government was after him. He did not consider himself a radical. He was not interested in politics. He never carried a gun. He thought himself strictly a religious leader, a medicine man. But that was exactly why he was dangerous. The young city Indians talking about revolution and waving guns find no echo among the full-bloods in the back country. But they will listen to a medicine man, telling them in their own language: "Don't sell your land, don't sell Grandmother Earth to the strip-mining outfits and the uranium companies. Don't sell your water." That kind of advice is a threat to the system and gets you into the penitentiary.

The words we put into our songs are an echo of the sacred root, the voices of the little pebbles inside the gourd rattle, the voices of the magpie and scissortail feathers which make up the peyote fan, the voice from inside the water drum, the cry of the water bird. Peyote will give you a voice, a song of understanding, a prayer for good health or for your people's survival.

---

The peyote staff is a man. It is alive. It is, as my husband says, a "hot line" to the Great Spirit. Thoughts travel up the staff, and messages travel down. The gourd is a brain, a skull, a spirit voice. The water drum is the water of life. It is the Indians' heartbeat. Its skin is our skin. It talks in two voices-one high and clear, the other deep and reverberating. The drum is round like the sacred hoop which has no beginning and no end. The cedar's smoke is the breath of all green, living things, and it purifies, making everything it touches holy. The fire, too, is alive and eternal. It is the flame passed from one generation to the next. The feather fan is a war bonnet. It catches songs out of the air.

In my dream I had been going back into another life. I saw tipis and Indians camping, huddling around a fire, smiling and cooking buffalo meat, and then, suddenly, I saw white soldiers riding into camp, killing women and children, raping, cutting throats. It was so real, much more real than a movie sights and sounds and smells: sights I did not want to see, but had to see against my will; the screaming of children that I did not want to hear, but had to all the same. And the only thing I could do was cry. There was an old woman in my dream. She had a pack on her back-I could see that it was heavy. She was singing an ancient song. It sounded so sad, it seemed to have another dimension to it, beautiful but not of this earth, and she was moaning while she was singing it. And the soldiers came up and killed her. Her blood was soaked up by the grass which was turning red. All the Indians lay dead on the ground and the soldiers left. I could hear the wind and the hoofbeats of the soldiers' horses, and the voices of the spirits of the dead trying to tell me something. I must have dreamed for hours. I do not know why I dreamed this but I think that the knowledge will come to me some day. I truly believe that this dream came to me through the spiritual power of peyote.

The hostility of the Christian churches to the Sun Dance was not very logical. After all, they worship Christ because he suffered for the people, and a similar religious concept lies behind the Sun Dance, where the participants pierce their flesh with skewers to help someone dear to them. The main difference, as Lame Deer used to say, is that Christians are content to let Jesus do all the suffering for them whereas Indians give of their own flesh, year after year, to help others. The missionaries never saw this side of the picture, or maybe they saw it only too well and fought the Sun Dance because it competed with their own Sun Dance pole-the Cross.

I pierced too, together with many other women. One of Leonard's sisters pierced from two spots above her collarbone. Leonard and Rod Skenandore pierced me with two pins through my arms. I did not feel any pain because I was in the power. I was looking into the clouds, into the sun. Brightness filled my mind. The sun seemed to speak: "I am the Eye of Life. I am the Soul of the Eye. I am the Life Giver! " In the almost unbearable brightness, in the clouds, I saw people. I could see those who had died. I could see Pedro Bissonette standing by the arbor and, above me, the face of Buddy Lamont, killed at Wounded Knee, looking at me with ghostly eyes. I saw the face of my friend Annie Mae Aquash, smiling at me. I could hear the spirits speaking to me through the eagle-bone whistles. I heard no sound but the shrill cry of the eagle bones. I felt nothing and, at the same time, everything. It was at that moment that I, a white educated half-blood, became wholly Indian. I experienced a great rush of happiness. I heard a cry coming from my lips:

Ho Uway Tinkte.

A Voice I will send .

Throughout the Universe,

Maka Sitomniye,

My Voice you shall hear:

I will live!