tl;dr: lib-washed simplification of a complex political moment in Chinese history, that delegitimises violence as an appropriate response to state repression, by only platforming nonviolent and reformist actors. Approach with extreme caution, and supplement with more honest accounts of Tianamen Square, that elaborate on the multivalence of political demands and actors.

—

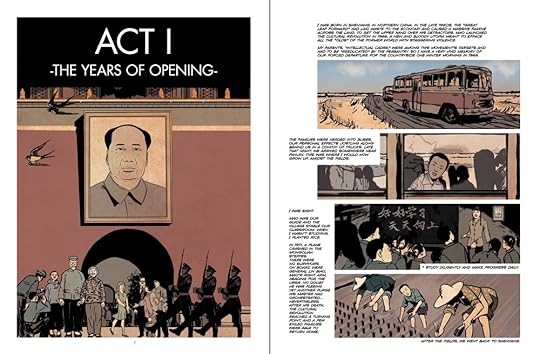

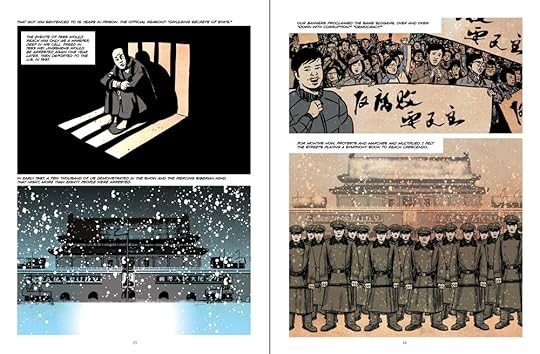

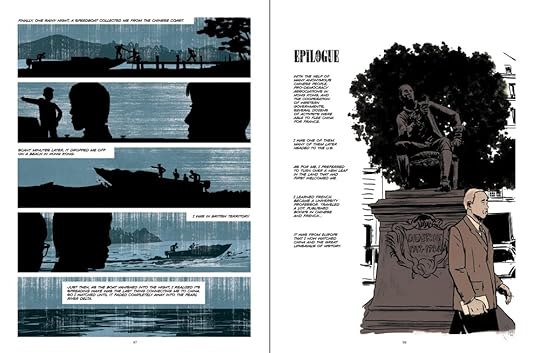

A gorgeous graphic novel that feels both too dense and too sparse in its narration. It relies heavily on direct exposition (walls of text), yet gives too little historical context into the events that led up to Tianamen Square. Zhang doesn't elaborate what life was like under Mao's Cultural Revolution, nor why Deng's celebrated takeover turned bitter over the years. His characters are vivid, but there's not enough context to grasp their material struggles. The subsequent crackdowns, before and during Tianamen Square, end up resembling totalitarian tropes: censorship through police and military repression (imprisonment, torture, maiming, and murder of political dissidents, students, and supporters); and disinformation campaigns by state media (representation of nonviolent protestors as counter-revolutionary terrorists).

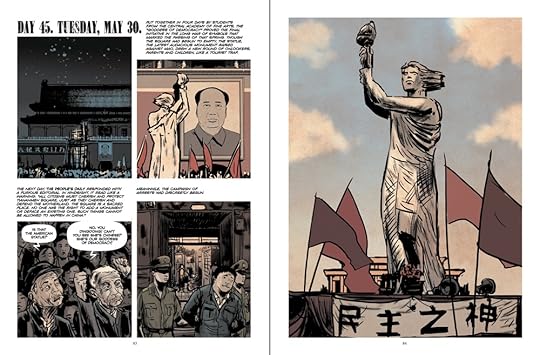

Zhang argues that the protestors at Tianamen weren't revolutionary, but reformist.* They didn't want to overthrow the state, they wanted to hold it accountable. It speaks volumes about the CCP that such a meek demand is met with tanks and open fire (by the People's Liberation Army of all things). The students at the square didn't even have weapons, and the worst act they committed was defacing a portrait of Mao.** Yet, the students pose a deeper threat to the CCP that Zhang either doesn't see or purposefully elides. The students may have been reformist in praxis, but they were revolutionary in ideals. They wanted true communism, the realisation of their education. They threw communist slogans back at the state and sang the internationale at night. The Beijing Autonomous Workers Federation, a group curiously absent from the book, called for workers' self-management. The threat of all nations communist-in-name-alone is that power truly does reside in the people. Hence the repression of such people, no matter how meek their claims appear.

—

*I've been doing some independent fact checking since finishing this, and Zhang has done a hell of a lot of historical revisionism to downplay the radical elements of the student movement. There were students outright calling for the overthrow of the CCP and, by extension, the ruling class of bureaucrats.

**Zhang has also downplayed the violent tactics of students. He didn't outright lie when he said the students in Tianamen Square were nonviolent, but there was violence outside of Tianamen Square and in other cities across China. Students and their supporters intercepted and ransacked buses filled with military weapons and supplies. There were roadblocks, rioting, beatings, and arson.

I find these distortions egregious. Zhang clearly wants to paint Tianamen Square as a peaceful protest for the liberalisation of China, but it was so much more than that. Yes, there were liberals in the free press and free market camps, but there were also socialists demanding the reinstitution of social services destroyed by economic liberalisation, and communists pushing for workplace democracy and revolution against an oppressive and nepotistic ruling class. Zhang avoids these complexities so he can position the student movement as an uwu peace parade. He stresses that police and soldiers sided with the students at various points during the occupation of Tianamen Square. Such moments matter of course. They speak to a shared grievance of life under the CCP, but by downplaying the conflicts between various social groups Zhang delegitimises violence as a form of appropriate resistance. Violence becomes the tool of the oppressor alone. This is naive at best and actively damaging at worst. It condemns an act that may be not only necessary for survival, but for change. Before soldiers began shooting, students threw rocks; after, they threw Molotov cocktails. Contrary to Zhang's depiction of the students as defenseless victims, they fought back, but only when provoked.

These stories matter, as much as the ones about solidarity and nonviolence, because they show us the organisation and courage of people pushed to the brink. Rather than pity them, we should respect them.