This book was far, far more than the story of the 1927 Mississippi River flood, the author skillfully presenting a number of other stories that while not directly about the famous flood, both impacted the flood and were impacted by it, stories that weren’t “one and done” so to speak but ones in which the author would present and then come back to to a greater or lesser degree, with the reader really appreciating I think why those other stories were told. I really admired Barry’s writing style, of dividing the book into different sections, centered around a certain time period, event, or a group of people, and within each section weaving a strongly narrative driven telling of history, providing information that really deepened the story of the flood, and most of all as far as making this a page turning book (and it definitely was), providing some sort of conflict for the reader to get carried away by, some sort of clash between people.

As I said the book isn’t all about the flood and from my notes the flood isn’t even in the book till about page 179. The reader in the first section is treated to the epic, hubris-filled, very strong and willful personality, man can conquer nature and shape nations by his sheer will, very on-brand for the 19th century story of three different engineers who tried to shape the Mississippi River in terms of navigation, commerce, and flood control, their actions impacting a large percentage of the country’s land area, population, and commerce, the decisions and legacies of these three men – James Eads, Andrew Humphreys, and Charles Ellet – and of the organizations that carried out (or ignored) their findings and decisions having an enormous impact on how damaging the 1927 flood was (specifically the “levees” only policy that was eventually adopted by the Mississippi River Commission, a policy “that Eads, Humphreys, and Ellet had all violently rejected”). It was interesting to note as titantic as the fight between Humphreys and Eads especially was (very much worthy of its own book), they both agreed along with Ellet that a levees only policy to deal with flood control was a mistake, with eventually the policy followed “combined the worst, not the best, of the ideas of Eads, Ellet, and Humphreys,” with over time the positions taken by the Mississippi River Commission becoming “increasingly petrified and rigid.”

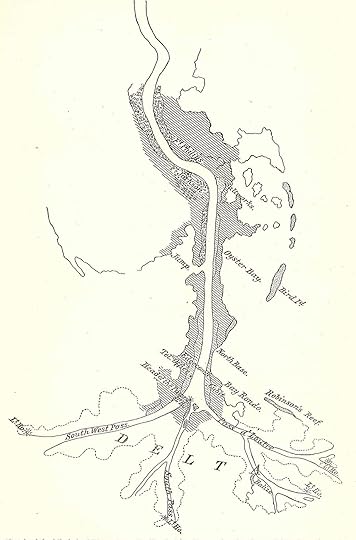

Oh and what does levees only policy mean? Without getting overly technical or weighing down the narrative with too much engineering terminology, the reader is treated to the nuts and bolts as it were of how rivers are improved upon for navigation and most especially how the lands around the river are protected from floods, be it through levees (basically earthen structures built a little back from the river to contain high flood waters), outlets (essentially places for flood waters from the Mississippi River to go, places for the river to escape), reservoirs (while outlets drain off water from the Mississippi itself, reservoirs were a place to withhold flood water coming from tributaries to the Mississippi), and cutoffs (cutting a line “through the sharp S curves of the river; these cutoffs would move the water in a shorter and straighter line, increase its slope, and hence its speed” serving to both move flood waters out of an area faster and to help scour out the river bed, allowing for a deeper river without making flood waters higher). The reader learns to their probable dismay that after all the Epic Fights over the control of the river, pretty much a levees only policy was adopted, one that created hundreds and hundreds of miles of wall-like levees lining the river, with no place prepared for the inevitable breech (crevasse is the term used) when (not if) that happened and no place for flood waters to go other than eventually the Gulf of Mexico.

Before, during, and after the actual coverage of the 1927 flood in the book, one gets the story of two areas, the Mississippi Delta (especially Greenville and Washington County Mississippi) and of New Orleans for three reasons. One, the areas were either hard hit by the floods (as Greenville was, with the town virtually destroyed, homes and businesses wiped out, and sadly poorly recorded numbers of people dying when the crevasse opened up and a wall of water poured forth, drowning people immediately or later washing out the foundations of houses where people had sheltered, killing them then) or the story from that point of view had a big impact on the overall story (the fight to save New Orleans from the approaching flood waters was a huge part of the overall narrative of the 1927 flood, and some of the actions taken to protect the city actually made things worse for others, as pretty much unelected people – bullying elected people into supporting these actions – dynamited the levees, deliberately flooding areas that looked like they wouldn’t be flooded [St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes], all to relieve the Mississippi of a good bit of its flood waters and hopefully save the city). Two, these areas, the Delta and New Orleans, were forever changed as a result of the flood (though the author admits that though the flood wasn’t the only cause for some of these changes it was either the biggest cause or the final push that lead to massive changes for these two areas), with the Delta region seeing a large flight of blacks after the flood, a huge labor pool migrating away, no longer allowing for the enormous Old South cotton plantations that used to exist there (and the political and cultural influence of the Old South plantation aristocrats, their last real place the Delta, finally ending), and marked a turning point in the fortunes, power, and prestige of New Orleans, of the city no longer being the biggest and most important port and city in the South and marking its long slow decline and increasingly insularity. Three, the gripping drama (and outright horror) of what happened in those areas, of treacherous politics in New Orleans that lead to the dynamiting of the levees, destroying the homes and livelihoods of others, and later the rather corrupt and miserly Reparations Commission that did all it could to pay little or nothing to those affected by the flooding of St. Bernard and Plaquemines Parishes, the decisions they made ruining people and businesses left and right, all after very public and solemn pledges that the city would do everything to make right and take care of those affected by the decision to flood those two areas.

As gripping as the New Orleans saga was, I think even more riveting was what happened in Greenville, Mississippi, of the almost Shakespearian rise and fall of one of the biggest personalities of the book, LeRoy Percy, the dominant figure and practical benevolent feudal lord of Washington County, a former U.S. Senator, close friend of Teddy Roosevelt, governor of a Federal Reserve bank, a trustee of the Carnegie and Rockefeller Foundations, and close friend to two chief justices of the Supreme Court, a man who early on was an enormous ally of the black people of Washington County, engaging in epic and very public fights with the Ku Klux Klan, of fighting hard to stop lynching, of making sure both blacks and whites got for Mississippi well-funded public education, of seeing to the cultural development of the entire county and especially of Greenville, building up a huge legacy of trust and admiration from the black community, all of it to come to an ugly demise with the flood as it became clear to all that Percy didn’t do all of this out of love for the blacks as people but for his very clear and logical understanding that the plantation economy and his wealth and power would collapse if black workers left, his fights to protect black people more about preserving a labor pool than doing the right thing for its own reason. The author painted a very complex picture of LeRoy Percy, at times corrupt, at times benevolent, definitely standing up to very bad people at great risk, but then in the end essentially a man who created an empire and defended it, helping when needed but for his own reasons. Decent sized sections of the book were essentially a biography of LeRoy Percy and that was more than ok with me, as he more than anyone represented the old Mississippi Delta, his actions kept it going as long as it did, and was the most ruined perhaps of anyone in power by the 1927 flood.

The author doesn’t just focus on the fall of Percy either as far as the coverage of Greenville goes, but also on the very sad state of affairs of the African Americans in Washington County. Helping squash efforts to evacuate them from the county – something that was doable and in fact was being done until there was an intervention – Percy feared that once the black laborers left, they would never return for that is what they were in the end, laborers. Forced to stay on the levee (though right next to the river, the only dry spot for miles and miles except for a few high buildings in Greenville), they were forced to work night and day wherever directed, often at gunpoint (as one black minister wrote, “being made to work under the gun…mean and brutish treatment of the colored people is nothing but downright slavery”), unpaid, with for a time little shelter and living in squalid conditions, with only the foods the whites allowed them to have (whites picking and choosing from Red Cross relief supplies what was “suitable” for the blacks), with whites only as overseers and bosses, never laborers shoring up levees before the crevasse or later on unloading boats with relief supplies. A sad but gripping tale, one that became a national scandal, it was sadder still to read that even after people were finally able to leave the levee, the Percys (including his son, William Alexander Percy, also a major figure in the book) continued to make race relations worse and if anything exacerbate black migration from the Delta.

As a reader I enjoyed the vivid contrast with how the flood destroyed LeRoy and William Alexander Percy but created the rising star of Herbert Hoover, a nationally known figure before the flood but one very much a political outsider, not even considered a long shot to be the next president of the United States (if Calvin Coolidge didn’t run for a third term, something prior to the flood no one knew for sure), but after his very public ownership of flood relief, coordinating federal and state agencies and the Red Cross to provide relief and save lives throughout the affected areas, becoming a national star and in the end essentially by far the most obvious candidate from the Republican party for president.

However Barry was far from glowing in his portrayal of Hoover, a man he called “a brilliant fool,” brilliant in terms of grasping and solving problems, of understanding issues and coming up with effective and original solutions, but also foolish in “deceiving himself,” rejecting “evidence and truths that did not conform to his biases,” and fooling “himself about what those biases were.” Thanks to Hoover, of how his behind the scenes campaigning to become the candidate for president was conducted, of how he did (or really didn’t) respond to the situation in Greenville, and his using of a national prominent black leader (Robert Russa Moton) to shore up support among black voters all while lying to Moton again and again about a resettlement plan in the Delta that would greatly benefit black citizens there, Hoover essentially started the beginning of the end of blacks being prominent in Republican politics and vital to their electoral chances, of really getting the trend going of blacks abandoning the party of Lincoln, the party that had fought the disenfranchisement of black voters and outlawing whites only primaries, that while Hoover was never racist, he did use black leaders and black voters for his own ends all while finding more white voters, lessening GOP dependence upon black voters.

I could go on for a while in my review, of talking about the strong personalities in New Orleans that were covered, of James Pierce Butler, Jr, J. Blanc Monroe, and Manuel Molero, of the weird, exclusive world of the various clubs, krewes, and Carnival balls of New Orleans society, of the role the flood had in the rise of Huey Long (who beat incumbent governor O. H. Simpson, who had approve the dynamiting of the levee to supposedly save New Orleans), of how very little Coolidge said or did about the flood despite numerous high level politicians begging him to do so, of how people feared people dynamiting levees on one side of the river to relieve pressure on levees on the other side of the river and so had guards that shot people on sight and even killed people, but other than what I just wrote, I won’t.

A really fine example of popular history writing, I had no idea how the 1927 marked the end or the beginning of so many things (most of what I mentioned in my review were endings, but one beginning was the result of a bill passed as a result of the flood and signed into law by President Coolidge, one in which the federal government would assume control over the lower Mississippi River, taking full responsibility for flood control, setting “a precedent of direct, comprehensive, and vastly expanded federal involvement in local affairs…a shift that both presaged and prepared the way for far greater changes that would soon come”).

The book has a section of black and white photographs of flood devastation and some of the people and places mentioned in the book, several maps, an impressive bibliography, and a comprehensive index.