What do you think?

Rate this book

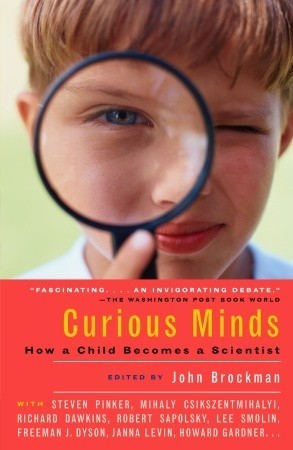

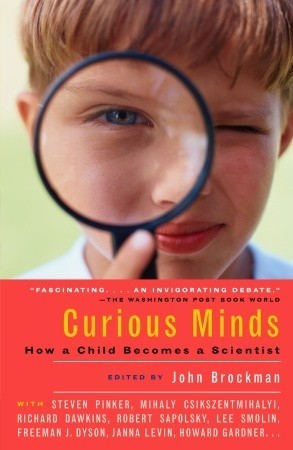

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 2004

My mother’s mother was one of the first women in Europe to get her PhD in chemistry. She lectured in Europe and ran a school for young women (the Stern Schüler) that her mother had started in the nineteenth century. My mother’s father was a physician and a colleague of Sigmund Freud (whose grandson Walter once proposed to my mother). My mother’s sister is a psychologist who has recently written books on the Jews uprooted by the Holocaust. My father’s father was an engineer, and my father’s brother was a gifted inventor, producing elaborate machines to automate European factories. George Parker, a cousin of my mother’s, was a talented electrical engineer for Bell Labs; his brother Frank was a brilliant intellectual and New York attorney. So it was not easy for a small child to get a word in edgewise at my family get-togethers. The intense and animated discussions were invariably about new ideas, usually those of intellectuals I had never heard of.

Don’t believe a word of what you read in this essay on the childhood influences that led me to become a scientist. Don’t believe a word of what you read in the other essays, either.

The conventional wisdom might have it backward. Rather than childhood experiences causing us to be who we are, who we are causes our childhood experiences.

When asked to submit an essay about our lives, we become content providers who edit the events into the satisfying arc of a good plot.

Chekhov remarked that if an audience is shown a gun in act 1, they can count on it going off in act 3. In composing a story line for our lives, knowing that a gun has gone off in act 3 tempts us to show it to the audience in act 1.

There is one more reason that autobiographies are less than truthful: We all want to look good. Experiments have shown that most people explain their behavior in ways that put them in the best light. We all sell ourselves as capable, noble, consistent, and in control of our lives, so that we can entice people to befriend us, trust us, or empower us. This explains the well-known phenomenon of cognitive dissonance reduction, in which people say they enjoyed a boring task for which they were paid a trifling sum because they don’t want to admit that they can be manipulated by social pressure.

The malleability of memory is the first reason why autobiographies should be taken with a grain of salt.

As the historian, whose name is Drew Gilpin Faust, observed, “We create ourselves out of the stories we tell about our lives, stories that impose purpose and meaning on experiences that often seem random and discontinuous.”

the psychologist Elizabeth Loftus put it, “Memory is a creative event, born anew every day. You fill in the holes every time you reconstruct an event in your own mind.” You fill them in on the basis of your current perspective, which may differ from the perspective you had when the event occurred.

And I think young women shouldn’t feel that they are defying the odds if they try to combine motherhood and a scientific career. I was lucky, but children—and science—shouldn’t have to rely on luck.

The first of these invisible causes is our genome. As the psychologist Hans Eysenck once said, the largest influence parents have on their children is at the moment of conception.

I chose my parents wisely.

(As an aside, I have no sympathy for the recent campaign to demote Pluto to a prominent Kuiper Belt object instead of a planet. Its weird orbit out there, usually but not always beyond the normal planets, is an inspiration to every kid who doesn’t fit in. Let Pluto remain a planet, now and forever!)

What Dr. Dolittle produced in me was an awareness of what we would now call “speciesism”: the automatic assumption that humans deserve special treatment over and above all other animals simply because we are human. Doctrinaire antiabortionists who blow up clinics and murder good doctors turn out on examination to be rank speciesists. An unborn baby is by any reasonable standards less deserving of moral sympathy than an adult cow. The prolifer screams “Murder!” at the abortion doctor and goes home to a steak dinner. No child brought up on Dr. Dolittle could miss the double standard. A child brought up on the Bible most certainly could.

The habit of questioning authority is one of the most valuable gifts that a book, or a teacher, can give a young would-be scientist. Don’t just accept what everybody tells you—think for yourself.

What is the single most important quality that suits you for a career in science? People often say “curiosity,” but surely that can’t be the whole story. After all, everyone is curious to some degree, but not everyone is destined to be a scientist. I would argue that you need to be obsessively, passionately, almost pathologically curious. Or, as Peter Medawar once said, you need to “experience physical discomfort when there is incomprehension.” Curiosity needs to dominate your life.

According to my theory, humans are innately motivated, as a result of their evolutionary history, to ally themselves with a group of others like themselves—for children, that means the peer group—and to tailor their behavior to that of their group. This process, called socialization, makes children more similar in behavior to their peers. But there is another process, operating at the same time, that makes children less like their peers: differentiation within the group. The members of a group differ in status, or are typecast by the others in different ways, which widens the personality differences among them.