What do you think?

Rate this book

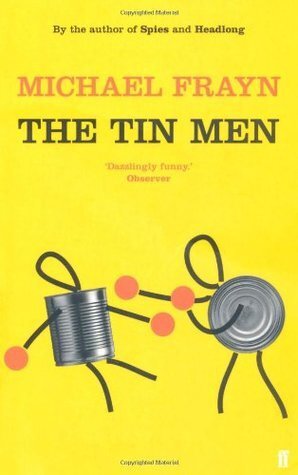

158 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1965

Say, for example, the randomiser turned up

STRIKE THREAT

By adding one unit at random to the formula each day the story could go:

STRIKE THREAT BID

STRIKE THREAT PROBE

STRIKE THREAT PLEA

And so on. Or the units could be added cumulatively:

STRIKE THREAT PLEA

STRIKE THREAT PLEA PROBE

STRIKE THREAT PLEA PROBE MOVE

STRIKE THREAT PLEA PROBE MOVE SHOCK

STRIKE THREAT PLEA PROBE MOVE SHOCK HOPE

STRIKE THREAT PLEA PROBE MOVE SHOCK HOPE STORM

Or the units could be used entirely at random:

LEAK ROW LOOMS

TEST ROW LEAK

LEAK HOPE DASH BID

TEST DEAL RACE

HATE PLEA MOVE

RACE HATE PLEA MOVE DEAL

Such headlines, moreover, gave a newspaper a valuable air of dealing with serious news, and helped to dilute its obsession with the frilly-knickeredness of the world, without alarming or upsetting the customers.