What do you think?

Rate this book

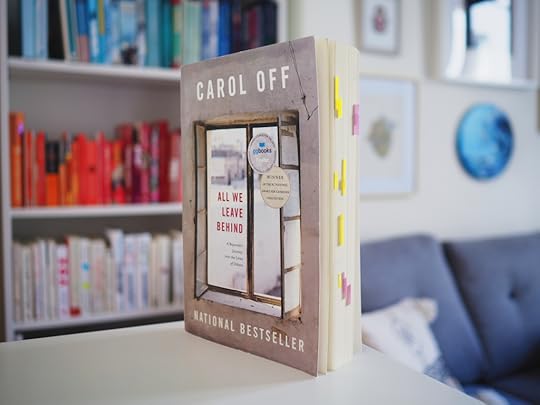

320 pages, Hardcover

First published September 19, 2017

I have no expectation that telling someone's story will fix anything because if I did, I would have an agenda and the truth would run the risk of being lost. I didn't return to Asad's side as a journalist; I did so as a human being. It was simply the right thing to do, a choice made in good faith. I appreciate that in my profession it's easy to become tangled in a cause and cross the line into advocacy. I understand why we have codes of conduct both in journalism and in society. But life is complicated. We do what we can and what we must.

For the previous ten years, billions of US dollars and USSR rubles had poured into Afghanistan to fund destruction but little else. By the end of the 1980s, half of all refugees in the world were Afghans, mostly exiled to Iran or Pakistan. A million and a half civilians had died because of war, while countless others were maimed and wounded; the International Red Cross estimated it would take 4,300 years to remove all the landmines that the contending armies had buried in the countryside. Afghanistan ranked third from the bottom in development of all countries of the world. Its children were severely malnourished. The place was swamped with Kalashnikovs, Stinger missiles, rocket launchers, armoured vehicles, bullets, bombs and angry disillusioned men.

Asad had risked his life when he spoke to the Canadian public broadcaster in an effort to warn our government that Canadians were unwittingly getting involved with the wrong people. I couldn't conceive of a better argument – Canada had an obligation to help.

"I saw in that interview how a question should be a key, sliding into the most reluctant lock and opening a portal on a private mind. Even the most guarded subject becomes vulnerable to the skilled locksmith [...]." (p. 10)The quote below was one of my absolute favourite ones within the book. Having a very personal story that illustrated it, made the whole narrative additionally captivating.

"The lesson I learned that day is that journalists all too often have their best moments when other people are having their worst." (p. 4) What turned out to be problematic for me personally, was how detailed the descriptions of the conflict in Afghanistan were. I felt like you had to go into reading this book with an already existing and strong knowledge, otherwise you would get knocked off your feet with all the background and historical facts, as well as all the new names of people and places within the first half of the book. It ended up being too heavily loaded for me, which was one of the reasons why it took me 18 days to finish the book. Nevertheless, I do have to say that everything possible has been done in order to ease your comprehension: A map of the concerned regions was added in the beginning, as well as a chronological glossary of the significant events in the end, so I'd definitely give it an A for effort!

"The Rahmans had wealth and a sophisticated world view and yet Habib limited the women's freedom at home , bound as he was to culture and tradition." (p. 47)A big part of the story is also dedicated to an immigration debate - how to leave one's own country if your life is in danger and all the obstacles that are put in your way, even if you have the most valid reasons to receive the needed support. The descriptions of all the bureaucracy linked to such a life changing experience are harrowing and they open up a whole new understanding of ones own privileges of living life in security. The whole story makes you appreciate and cherish your situation, if you don't live in fear for your life and the one of your loved ones on a daily basis.

"They feared women as dangerous creatures who appealed to human weaknesses and wicked appetites. They believed men needed protection from women. Women needed protection from their own vanity." (p. 110)

"The girls' existence in Kabul was without play, joy, or celebration of any kind. They were not permitted the kiss of the sun on their faces or the flutter of a breeze through their hair. They dared not look out a window without wearing a burqa for fear of being seen by the police who sometimes ordered windows to be whitewashed so passersby could not be tempted by even a glimpse of a female face." (p. 112)

"The seething centre of the refugee debate is not really about policy; it's about perception. Either you identify with others or you don't. Either you see yourself in the eyes of others or you don't." (p. 275)What I was longing for after finishing the book, was to watch the two mentioned documentaries in the beginning, which the author produced after her trips to Afghanistan. It's a pity that I wasn't able to find them online, but at least there is this short and very interesting video I came across. It adds a visual layer to the story but since it's a bit of a spoiler, I'd suggest you to watch it in the end of the book.

"What differences flow from a simple accident at birth. In one country a man speaks his mind and his world falls apart; his children are left without a future and they live in abject terror for years." (p. 241)

"If a journalist asks good questions she might win an award. If someone answers good questions it might get him killed." (p. 279)