The title of Lahiri’s latest book—Unaccustomed Earth—refers to the first story in this collection but also to a motif dominating all of the stories: tales about a world unaccustomed to the shifts and changes taking place on its surface, a world uncomfortable with the destruction and loss brought on by hurricanes and tsunamis, unfamiliar with modern diseases and traumas, and unsure about the class and cultural conflicts that dominate relationships in the lives of Lahiri’s characters. The earth that we now inhabit, Lahiri seems to be saying, is one that our ancestors would not recognize.

Despite the uniqueness of modern society, the emotions and situations that Lahiri depicts are universal. Since reading her Pulitzer Prize-winning 1999 collection, Interpreter of Maladies, I have believed that Lahiri is one of the best writers of our generation, and—like her 2003 novel, The Namesake—Unaccustomed Earth provides only more evidence of this fact. What makes Lahiri’s work so accomplished and simultaneously riveting is that, unlike her literary peers, Lahiri is more concerned with substance than style. Her stories are about real people rather than quirky characters or odd situations. . . people we know, people we love and hate. The stories are about those we care about most letting us down because they are incapable of having healthy relationships— like Rahul in “Only Goodness” and Farouk in “Nobody’s Business.” And they are about parents who return to us or finally abandon us like the father in “Year’s End.”

There are no gimmicks in Lahiri’s prose, no writing with a capital W, the kind that so annoyingly draws more attention to itself than its characters. This is simply straightforward storytelling about issues to which we all can relate. And, in that way, every one of the eight stories in Unaccustomed Earth does exactly what Stephen King said great stories do when he was hawking the 2008 edition of Best American Short Stories in The New York Times Book Review last fall: they grab us and make us hold on tight, they come at us “full-bore, like a big, hot meteor screaming down from the Kansas sky.”

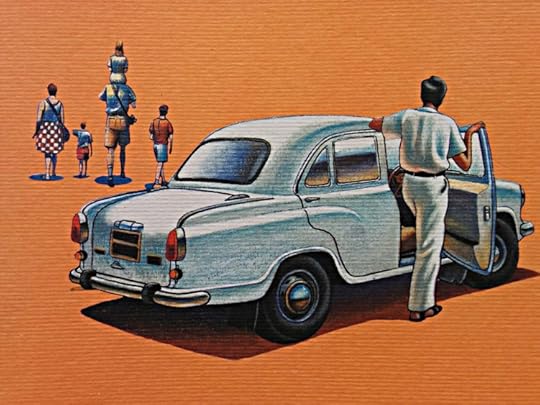

But it’s not only that Lahiri pulls us in emotionally, it’s that she makes us reconsider our choices and reflect on them by making connections between her fictional characters and our own experiences. She navigates the personal and the political, and the stories touch on a variety of issues we care about: marriage, divorce, death, disease, dislocation. As in her first collection, the stories in Unaccustomed Earth take on the contemporary question of liminality and hyphenation: Who are we when we are not one person, but not another? When we are both at the same time? What does it mean to be from a place but not of it? Why do we resist the unknown? In “Going Ashore,” she demonstrates how it is that one might find oneself without a cultural home, nomadic not by choice but by circumstance. In some ways, the difference between this collection and The Namesake and Interpreter of Maladies—which both seem, in some ways, to wax nostalgic about immigration—is that Lahiri is more antagonistic about issues of diaspora, not only bringing them out of the closet and wearing them in public, but also getting them dirty, ripping the seams out, and showing us how they’re constructed.

An inherent criticism of those who resist assimilation is an underlying premise of the book. Unlike one of the most moving stories in her first collection, “The Third and Final Continent”—which, in some ways, reads like a love letter to arranged marriage—several of Lahiri’s stories in this book take aim at the practice: “Heaven-Hell” tells the story of a woman who tries to burn herself alive after falling in love with her husband’s young protégé, a man closer to her in age than her own spouse. And in the title story, the father of the protagonist falls in love with another woman after his wife’s death—the first time he has ever truly been in love—an emotional shift that allows him to connect more fully with his daughter. This theme reappears in the three outstanding stories that make up Part Two: “Hema and Kaushik.” In these connected stories, Lahiri gives the reader not one, but two marriages based on convenience rather than love.

But Lahiri never hits us over the head with these messages, and sometimes they are so subtle that we have to be on the lookout in order to see the meaning that lies under each story’s surface. Nancy Zafris, former fiction editor of The Kenyon Review, said once that great stories “must always be telling two or more stories in a way that disguises for a while the real story,” and Lahiri has learned this lesson well, layering every story with numerous complexities.

In “Nobody’s Business,” an American graduate student discovers that his Indian housemate’s boyfriend, an Egyptian, has been cheating on her for years. When the American inserts himself into this drama, he finds his help is unwanted. Even though it is the philandering boyfriend who tells him, “I didn’t invite you here,” the reader still feels violated by the American’s unwanted presence. On the one hand, we hope the American can help his Indian housemate, but at the same time, we want to tell him to get lost, raising the question of whether it is better to turn a blind eye to the problems of others or try to help them out of the messes in which they find themselves. There are other implicit criticisms of the U.S. in the book as well. According to the narrator of “Once in a Lifetime,” America is known first as a place where class “differences were irrelevant,” but as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that under the surface, the petty jealousies and judgments that affect relationships between people from different social strata still fester, a theme also echoed in “A Choice of Accommodations” earlier in the book.

The stories similarly criticize human selfishness—showing parents who put their own needs first, children who are hung up on petty resentments, partners who feel little for their spouses, individuals who use each other for their own gain. And like people who are honest about their vulnerability, their fallibility, the reader cares for these flawed characters even more deeply as a result, grieving when they grieve, loving when they love. This unyielding sense of empathy is accomplished most powerfully in the stories about Hema and Kaushik. After uncovering a row of tombstones in the woods behind young Hema’s suburban home, a sixteen-year-old Kaushik tells her that he wishes that his family wasn’t Hindu so that his mother could be buried somewhere, a place where presumably they could—like the family he has uncovered under snow and fallen leaves—all be together again. It is this scene that stays with me long after I have finished the book, calling to mind again and again the metaphor uniting the collection—earth that is not accustomed—and raising the question of how we push this world, and those who inhabit it, to accommodate our all-too human whims and desires.

This review first appeared in Cairn 43: The St. Andrews Review.