An interesting mixed-history, which includes a professional biography of Ernest Lawrence, the Nobel Prize winning physicist, part history of science and technology in physics, and finally, a study on how technology development is managed in times of war. Lawrence, who was the primary driver in the development of the cyclotron, and who’s namesake lab, Lawrence-Livermore Labs at Cal-Berkeley has played a prominent role in atomic and high-energy physics, as well as the d development of high performance computing, for the past 70 years, is an interesting historical figure, who has sometimes been cast opposite of figures like Oppenheimer because of the stance they took in the early development of nuclear weapons (Lawrence was infamously ‘neutral’ on the morals of aiding the development of the bomb even after it was clear the Third Reich would collapse and did not have a viable competing program). This book sets to add more nuance to his position by casting his actions within the greater history of development in science and technology in the early 20th century. For better or for wrong, Ernest was adamant on making his vision of “industrial-scale” experimental research into a reality, and he accomplished that in spades through his Radiation Laboratory (“Rad Lab”) in Cal, and later consulting/helping to stand up both Los Alamos and Oak Ridge.

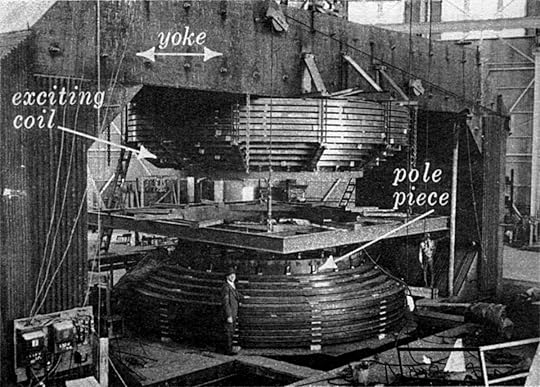

The book’s narrative is divided into four historical segments, or quadrants. The first being a summary of Lawrence’s early life and how he came to join the Rad Lab and develop the Cyclotron, as well as champion its use across the globe. There’s a lot of familiarity with the way Lawrence organized his labs, including the flat managerial structure, that empowered the scientist, and not non-technical staff, as well as his encouragement of ‘tea-time’ sessions where new papers would be read in informal luncheons, that makes his lab look more like Google or Facebook than a early 20th century academic institution. The second quadrant focuses on Lawrence and the lab’s contributions during the prewar (WW2) period. Here, Lawrence engaged in significant networking, and played the part of a “champion” or evangelist for his lab and their technologies and methods. It is clear from these writings that the significant “cross-pollination” with various government officials, amateur/’gentlemen’ scientists, and influential philanthropic organizations, the most prominent of the later 2 being Alfred Loomis and the Rockefeller Foundation, helped guide the pre-war US administration craft a likely strategy to pioneer several technologies, including contributing to radar, and of course, the completion of the Manhattan Project.

The third part of the book is all about Lawrence’s wartime activity, specifically his work for the Manhattan Project. Here we see he and the Rad Lab’s influence in the development of both Los Alamos and Oak Ridge Labs, which was the first true industrial-scale lab built from the ground-up to serve that mission and structure in the United States, as well as Lawrence’s hands toward guiding the development of the bomb from feasibility stage to the largest engineering project ever attempted by any nation up to that time.

I appreciated the details that were present in this section of the book, including his contribution towards the feasibility studies on uranium enrichment. Though Lawrence selected a method that was found less desirable in the post-war years, the so-called electromagnetic isotope separation, which was less practical than the gaseous diffusion procedure, it was the enriched uranium generated from this process that ended up in “Fat Man” and “Little Boy”

The final section of the book, on the post-war years, tells the story of Lawrence’s contributions to nuclear policy, and deals with the ethics (and wisdom) of his “principled” neutral stance in aiding the US development of atomic and thermonuclear technology. The main event here is the development of “the Super”, which was the first hydrogen bomb. Here, the book intersects heavily with biographies of Oppenheimer in his later years, as the theme is really focusing on the ethics of science, to paraphrase Oppenheimer, “Physicist now know sin”, and it was the responsibility of scientist to attempt to guide their governments away from the destructive policies of arms-race that increased risk of total annihilation.

There’s some interesting commentary here on the early thinking of nuclear warfare, especially on the possibility to unilaterally stop the arms race (on the US side), as well as the idea of “internationalizing” nuclear weapons control. People who’ve read books like “Raven Rock” or “Command and Control” will find a nice supplement to those topics in this 4th section of the book here which should augment their knowledge of those subjects decently.

Overall, I am satisfied with this book, it has added more color to the role scientists and engineers played during the early and mid 20th century, and serves as a good case study of how scientists should conduct themselves in times of great change. It enlightens the general reader on the life of Ernest Lawrence, an obscure, but greatly impactful figure in the history of science and technology, as well as informs on the nature of the genesis of the military-industrial complex. Finally, it is a great supplement to the history of the strategic arms race, especially at the start of that race, and can help inform modern thinkers how one may seek to incorporate new technology to national policy, especially those that are potentially highly destructive. Highly recommended.