What do you think?

Rate this book

96 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 1986

‘in Hilst's formulation, the obscene is differentiated from the erotic and the pornographic by its philosophical and spiritual elements, and also through its act of social provocation.’

‘I looked at numbers formulas equations theorems and it was a pleasure, a fiery freeze, a bodyguard for wandering alone without the speech-rupture of others, logicality and reason and nevertheless the possibility of a surprise as though we were unfolding a piece of silk, blue triangles on the fresh surface and suddenly just a dull little grid, lines that we can separate and recompose into triangles again, yes, this we could do, but where did the blue get to, where?’

from here i can hear him comparing the lucidity of an instant to the opacity of infinite days, i can hear him thinking of the various manners of madness and suicide. the madness of the Search, which is made of concentric circles and never arrives at the center, the obscuring, incarnate illusion of finding and understanding. madness of the refusal, one of saying everything's okay, we're here and that's enough, we refuse to understand. the madness of passion, the disordered appearance of light upon flesh, delicious-tasting chaos, idiocy feigning affinities. the madness of work and of possession. the madness of going so deep and later turning to look and seeing the world awash in vain slaughter, to be absolutely alone in the depths.

Eu gosto MUITO da prosa de Hilda, mesmo com sua lógica que quase "beira o esquizofrenismo", como a própria autora diz sobre alguns trechos desse livro. Para mim, essa literatura é puro charme, um charme que vai do mais baixo do ser humano até o mais poético em um só parágrafo, sem dar o nexo descritivo ao leitor ou se quer mesmo um senso lógico descritivo. E, por conseguinte, os sentimentos vem à tona, te pegando desprevenido.

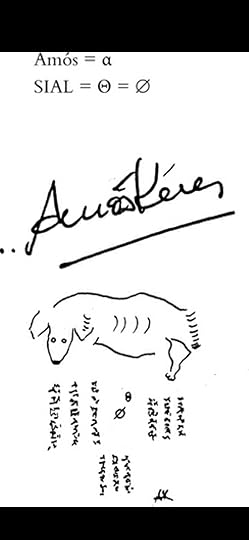

Em termos de narrativa, "Com meus olhos de cão" versa sobre um matemático que busca razão à vida, amante da lógica e da literatura, esse se perde em seus pensamentos. Deus? uma Superfície de Gelo Ancorada no Riso.