What do you think?

Rate this book

308 pages, Hardcover

First published February 1, 2015

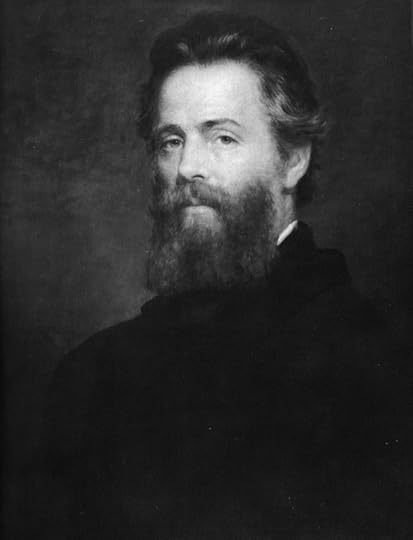

He pointed out that “a strong lack of conscience” is one of the hallmarks for these individuals. “Their game is self-gratification at the other person’s experience,” Hare said. “Psychopathic killers, however, are not mad, according to accepted legal and psychiatric standards. The acts result not from a deranged mind but from a cold, calculating rationality combined with a chilly inability to treat others as thinking, feeling humans.” - the author quoting Robert Hare, author of a book on PsychopathyCall me Will. Some years ago, a lot, don’t ask, I thought I would see a bit of that northern rival city. It was wintry, snow on the ground. Accommodations were meager. No, I was not there alone, and the journey was not without portents. But I was spared a room-mate of the cannibalistic inclination. I still feel the pull, on occasions. Maybe stop by to see relics of Revolution, fields of dreams crushed and fulfilled, walk spaces where giants once strode. So I was drawn to Roseanne Montillo’s latest. In her previous book, The Lady and Her Monsters, she followed the trail of creation blazed by Mary Shelley as she put together her masterpiece, Frankenstein. In The Wilderness of Ruin, Montillo is back looking at monsters and creators. This time the two are not so closely linked. The monster is this tale is all too real, the youngest serial killer in US history. The artist in this volume is Herman Melville (and, of course, his monster as well, but the killer is the primary monster here). Montillo treats us to a look at his life, or at least parts of it, and offers some details on the elements that went into the construction of his masterpiece, Moby Dick. A consideration of madness, in his work and in his life, and public discourse on the subject of madness links the two. A third character here is Boston of the late 19th century, as Montillo offers us a look at the place, most particularly in the 1870s. I am sure there are parts of the city remaining, in the Fenway-Kenmore neighborhood, for one, where a form of madness is regularly experienced.