What do you think?

Rate this book

238 pages, Kindle Edition

First published August 7, 2018

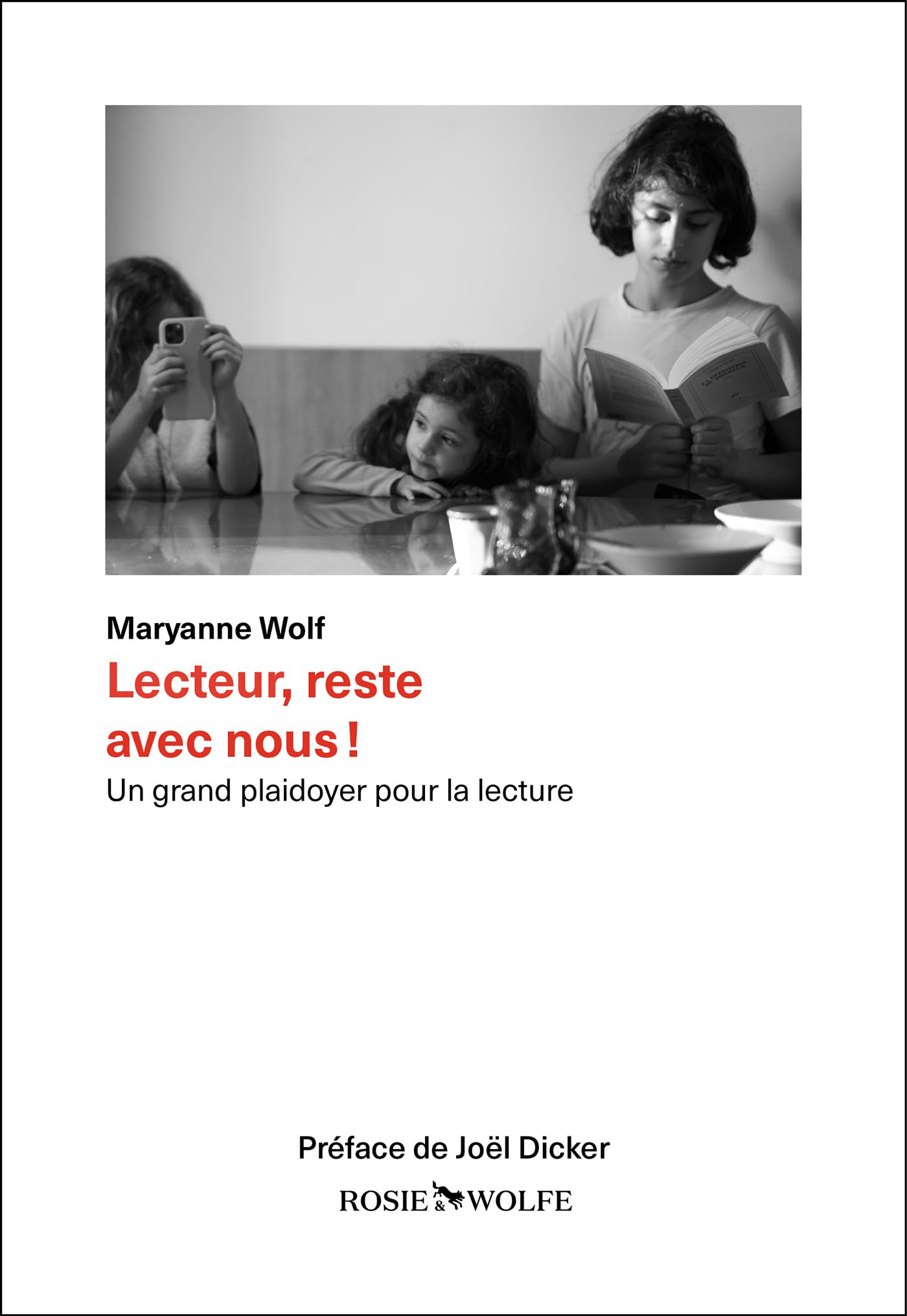

"Young people have such short attention spans these days. And with publishing, kids have instant entertainment in the pockets of their puffling pants. Oh, you see them hanging around together, hunched over a book of 14-line iambic pentameter, thumbing away, transfixed like zombies. Not talking to each other. Not interacting socially. Lost to the world. "Get off your book of sonnets!" cry parents up and down the land. "You'll develop a hunch!" I do worry about how their brains will develop with so little variation of stimulus to challenge their imagination.".

“When you read carefully, you are more able to discern what is true and to add it to what you know. Ralph Waldo Emerson described this aspect of reading in his extraordinary speech ‘The American Scholar’: ‘When the mind is braced by labor and invention, the page of whatever book we read becomes luminous with manifold allusion. Every sentence is doubly significant.’ In reading research, the cognitive psychologist Keith Stanovich suggested something similar some time ago about the development of word knowledge. In childhood, he declared, the word-rich get richer and the word-poor get poorer, a phenomenon he called the ‘Matthew Effect’ after a passage in the New Testament. There is also a Matthew-Emerson Effect for background knowledge: those who have read widely and well will have many resources to apply to what they read; those who do not will have less to bring, which, in turn, gives them less basis for inference, deduction, and analogical thought and makes them ripe for falling prey to unadjudicated information, whether fake news or complete fabrications. Our young will not know what they do not know.”