What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published September 1, 2013

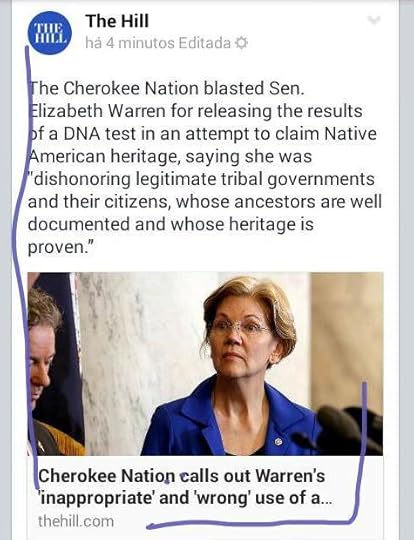

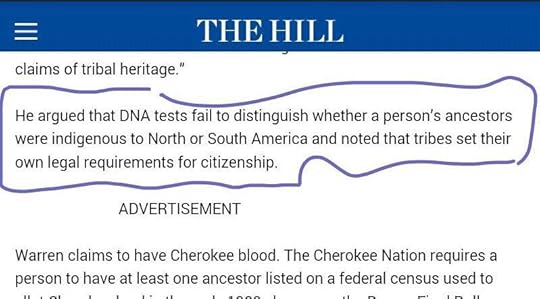

One thing I kept thinking about throughout the book was how many people in the US have no idea of their origin. This is in large part because of how racism works here. It's so attractive to everyone who has lost their knowledge of family to take a DNA test and get a list of markers that might tell them something about their origins. Yet these tests can only give hints, not conclusive information. Tallbear talks about another anthropologist's research into white people who believe they have native ancestry--and why they always think they are Cherokee. Over the summer we had two visits to our little Jewish community from people who took genetic tests that showed they had Jewish ancestry. Did they? For historically stigmatized groups, self-definition is a critical right. There will always be times when the rights of individuals to self-definition and the rights of the group to self-definition are in conflict. To Tallbear, these moments are fraught with the content of the specifics of the racist ideas leveled against indigenous people: that they don't know themselves as well as white people know them, that white people get to define them.

This was a very valuable book for me. The first time I understood that genocidal attitudes toward native people in the US were an ongoing issue was in the late 1980s when I read a New York Times op-ed by an activist who wanted to get his tribe's bones back from the Smithsonian. As a Jewish kid, raised with the visceral horror of Nazis treating Jewish bodies like objects, I was nauseated by the idea that I'd gone to these kinds of museums. Far from being all scientific and clean, the exhibits I was witnessing were exhumed human remains, taken without permission of living descendants. Suddenly I could see that I was surrounded by racist caricatures of living people who were being harmed.

I'm teaching introductory courses that cover gender, race and class. Essentially I am teaching about something so big that I can never feel like an expert. I keep coming up with definitions of racism. One that works pretty well for me inside my own head is, "racism is a tacit justification to treat some people as though there are no laws or customs to protect them." In general it seems like a good thing for most people to be the subjects of scientific study. If we ignore all the laws and rules when we come to some people (some "populations" as Tallbear scare-quotes the term in the book) it can never be safe for them to be the subject of scientific inquiry. They will always be only objects. Organizations have ignored codified ethical standards in their research of native people and continue to do so. She ends the book with a plea for more native people to go into genetics, to colonize the field from within. Only in this way can science be transformed.

Although genes, the body, and life itself are actually constituted by many complex interactions between humans and nonhumans, gene fetishism leaves us with an impoverished understanding of DNA as a "master molecule" or as "the code of life". The molecule itself comes to be seen as the source of value and, in the case of Native American DNA, as a source of identify and potentially, then, a foundation for compelling claims