Wonderful play. So happy I read it – and re-read it, and watched it, then read it online – at least four-five times. :D

This is a play which has been heavily examined, reviewed, critiqued, and studied. (What play of Shakespeare’s has not?) But this one has come in for some meticulous scrutiny. First off there is the question of who wrote what when. Well, isn’t this the case with ALL his plays? And aren’t there multiple theories concerning the various supposed writers who really wrote the plays? Not as much as this one. (And I personally think saying Shakespeare wasn’t intelligent/educated enough to write this stuff is like saying the Easter Islanders were too stupid to erect their colossal, remarkable statues. Poppycock!) Anyhow, going all the way back to Alexander Pope, the experts have had their doubts. Because of style of writing, language choices, the meter or rhythm in certain sections of dialogue, many have said that Shakespeare, at least in this one, had assistance. That is to say, this play was written as a collaboration, with Will writing some scenes and others writing other scenes. What’s wrong with a collaboration anyhow? Isn’t that how things are often written today, esp. movie scripts and television series? Quite often credit is given to a writing team and I’ve seen many an academy award show where an entire group flocks up on stage, at any rate…

I think Will wrote most of it and if he had help, so what.

Another criticism I came across, (I research these suckers as much as read – or watch – them), concerns the battle scenes, of which there are many. Critics have said these scenes reduce the play to a more common or vulgar level, and that battle scenes belong off stage, or should be imagined. How does one do this? Through device of dialogue, of course. The actors should talk about or convey what’s going on. Okay, bollocks, I say to that. Can you imagine Lord Suffolk crying out, ‘Oh look, yonder, poor Talbot! Is that blood I espy upon his doublet! Ouch! Ow! He’s fallen, oh my lords, gentle lords, what tragedy this day doth befall on our gallant lads!’

Nah, fie on that too, and by the way they wouldn’t say lads. I made that up.

Anyhow, whoever wrote the play, and whoever decided to keep the several fight and battle scenes, to you say I hurrah! (And I especially like when a group of townspeople throw stones at each other and ignore all attempts – and by their betters! – to stop them. Bravo for the common man!)

As for the story, it doth goeth…

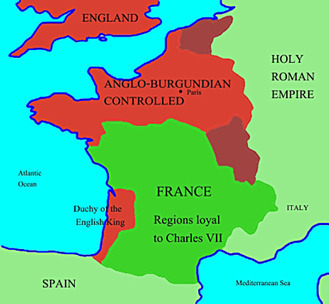

England has lost its king, Henry V, so the first scene is one of sadness, tragedy, death, and the like. Everyone mopes around worrying about things and it’s great foreshadowing for what is to come. In this play if someone is happy one moment, wait a few tics and he’ll be moping about or quarreling or maybe even be dead or dying in the next. France and England are at war. (Someone on a Youtube video said, well weren’t they always at war back then?) And there are scenes set in France, what with Joan of Arc running around getting the equally morose French all excited about winning again! There are also scenes where the English, led by the redoubtable Talbot are at the gates of this French city or that, winning, and sometimes losing.

Meanwhile, back home in England everyone’s getting accustomed to a new king, who’s actually an infant at this time in history. (Shakespeare (or his team) aged Henry so he could give great and rousing speeches.) There’s dissension between two notable leaders, both of whom want to be close to young Henry, the real source of power. These two are Winchester, head religious leader who eventually becomes Bishop; and Gloucester, the King’s Protector. These two really, really do hate each other and when they’re on stage you can expect fireworks – verbal and physical. If anyone tries to calm them down, they just ignore said person. (They really, really do.) Their followers are identified by the color of their coats: blue for Gloucester, tawny for Winchester. If I were watching this in the pit at the Globe I’d be all, ‘Bring on the tawny coats’, while my husband Hugh the mule-tender gives me a whack and cries, ‘Nie, the blue coats, foolish strumpet! The blue!’

There’s other plots a’brewing, too, in that you’ve got this bounder, Richard Plantgatenet, who’s told by his dying uncle – who’s shut up in the tower of London, kept prisoner for eons – that ‘Hey, ist thou, Richard, who should truly wear the crown!’ Apparently both Henry VI and Richard descend from different lines of the same last great king, Edward III. Slight problem, though. It seems that Richard’s father was executed for treason so this puts a damper on his family line. But don’t worry about that, because Henry VI is a nice guy, (whether he’s really a baby, teenager or whatever.) He generously restores Richard to his rightful titles and estates. Pity he does that, because now that Richard is rich and influential again and can gather a lot of toadies (followers) around him, he starts to think about this. There are several ‘asides’ in the play where Richard winks and talks directly to the audience – ‘Hey, maybe I am the true ruler? Methinks me needs to think on this.’

(I make up the pseudo-Shakespearean lines; please don’t blame Will.)

Anyhow, all this will ultimately lead to the War of the Roses, which is presaged in a scene in which supporters of Richard, the House of York, grab white roses as their insignia. (Or sigil as G R R Martin would call it.) And those who support the House of Lancaster, or King Henry VI, grab red roses. To anyone living in Shakespeare’s time, this would have been an ‘Uh Oh’ moment, foretelling the calamity yet to come.

(Shakespeare wrote this play in the relatively calmer time after the War of the Roses. It was past, yet recent history.)

So there are battles and arguments. Gloves thrown down and possible duels. Joan of Arc doing her thing and having others describe her as a strumpet and various plays on the word ‘Pucelle,’ which was a name she used which meant ‘the maiden.’ There’s also various puns and word play where Will uses everyday words in ways which turn their meaning sexual. (Oh, like we do today? Witness the SNL skit in which three actors discuss the various ways to ‘caulk’ a window. A riot today and in the past.)

A scene (or scenes) which I rather liked involves the death of the English military leader, Lord Talbot. He dies, then lives, then seemingly dies again. As I was reading I kept thinking, okay, there he goes – nope! He doth rouse himself in order to give sweet speech to his (also) dying son! What a man!

Anyhow, the play is a marvel. It’s crazy with action, great dialogue, then more action and the crowds must have loved this in its heyday. I know I did and I’m 400 years past its heyday.