What do you think?

Rate this book

166 pages, Hardcover

First published September 19, 2023

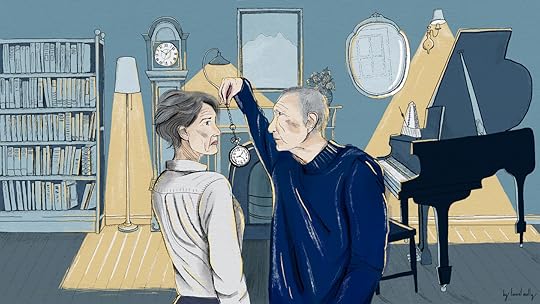

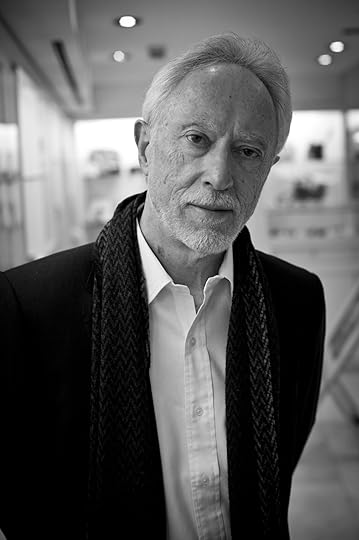

He is a Pole, a man of seventy, a vigorous seventy, a concert pianist best known as an interpreter of Chopin, but a controversial interpreter: his Chopin is not at all Romantic but on the contrary somewhat austere, Chopin as inheritor of Bach. To that extent he is an oddity on the concert scene, odd enough to draw a small but discerning audience in Barcelona, the city to which he has been invited, the city where he will meet the graceful, soft-spoken woman.

Producing a concert, making sure that every thing runs smoothly, is no small feat. The burden has now fallen squarely on her. She spends the afternoon at the concert hall, chivvying the staff (their supervisor is, in her experience, dilatory), ticking off details. Is it necessary to list the details? No. But it is by her attention to detail that Beatriz will prove that she possesses the virtues of diligence and competence. By comparison, the Pole will show himself to be impractical, unenterprising. If one can conceive of virtue as a quantity, then the greater part of the Pole’s virtue is spent on his music, leaving hardly any behind for his dealings with the world; whereas Beatriz’s virtue is expended evenly in all directions.

Years later, when the episode of the Pole has receded into history, she will wonder about those early impressions. She believes, on the whole, in first impressions, when the heart delivers its verdict, either reaching out to the stranger or recoiling from him. Her heart did not reach out to the Pole when she saw him stride onto the platform, toss back his mane, and address the keyboard. Her heart’s verdict: What a poseur! What an old clown! It would take her a while to overcome that first, instinctive response, to see the Pole in his full selfhood. But what does full selfhood mean, really? Did the Pole’s full selfhood not perhaps include being a poseur, an old clown?