What do you think?

Rate this book

496 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 250

I am very sorry that we have not a dozen Laertiuses, and also that he was not more expansive or more thoroughly informed. For I am equally eager to know the fortunes and lives of these great teachers of the world, no less carefully than their doctrines and ideas.—Montaigne, Book II, Essay X: Of Books

I for one prefer reading Diogenes Laertius, in [him] there lives at least the spirit of the ancient philosophers . . . The only critique of a philosophy that is possible and that proves anything, namely trying to see whether one can live in accordance with it, has never been taught at universities; all that has ever been taught is a critique of words by means of other words. —Nietzsche, Schopenhauer as Educator

__________

Equally uncertain is the reason for the text's survival: if Diogenes Laertius had readers in his own lifetime, we don't know who they were. The manuscript may well have been published only posthumously, prepared by a scribe forced to work with unfinished material. No one knows how many copies were initially made. Unlike the corpus of Plato, which was carefully preserved by his school, or the treatises of Aristotle, which came to be widely read, studied, and copied in antiquity, it's as if the manuscript had been preserved by a quirk of fate, just like the wall paintings in Pompeii. —James Miller, Introduction

__________

Let me now put the finishing touch, as one might say, to my entire work and to the life of this philosopher by presenting his Chief Maxims, thereby bringing the whole work to a close and offering as its conclusion the beginning of happiness . . . —Book 10, Epicurus

The Lives contains fifty-two epigrams by Diogenes on forty-six philosophers and twenty-nine epigrams by other poets, both named and anonymous, on twenty-three philosophers.and the ones which he includes of his own creation, usually concerning the Philosopher's death, come from his Pammetros, a collection of epigrams about various Philosophers. The first one he includes, about Thales, runs as follows:

One day as Thales watched the games,

You snatched the sage from the stadium.

I commend you, Zeus, Lord of the Sun, for drawing him toward you;

For he could no longer see the stars from earth.

The extant poems are so wretched as fully to justify van Gutshmid's thanks to Apollo and the Muses for allowing the collection as a whole to vanish. —Herbert S. Long

perhaps the worse verses ever published. —W. R. Paton

The real reason Diogenes had written his book, Nietzsche suggested, was to provide an artificial framework that would justify republishing the wretched epigrams he had written about the deaths of the philosophers. Nietzsche further speculated that these had been a total failure with the public when they had first appeared as part of a collection of his miscellaneous poems and that he was anxious to find a pretext for republishing them. —Glenn W. Most

Diogenes' own epigrams, when extracted in order from the prose accounts in his Lives, do at times show thematic continuity or other linking devices that are typical of carefully arranged epigram collections, such as Meleager's Garland.

Nobody would waste a word about the lowbrow physiognomy of this writer if he were not by chance the dim-witted watchman who guards treasures without having a clue about their value- Nietzsche

the Greeks, with whom not only philosophy but the human race itself began...("Obviously that Turk didn't invent philosophy, because he says god sucks cock".)

those who attribute [philosophy's] invention to barbarians bring forward Orpheus the Thracian, declaring him a philosopher and the most ancient. For my part, I do not know whether one should call a person who spoke as he did about the gods a philosopher. And what should we call a man who did not hesitate to attribute to the gods all human experience, including the obscene deeds committed rarely by certain men with the organ of speech.

[Plato says tyrants are bad.] In his anger Dionysius said, “You talk like an old fart,” to which Plato replied, “And you like a tyrant.” Vexed at this, the tyrant was at first eager to have Plato put to death; then, dissuaded by Dion and Aristomenes, he did not go that far but entrusted Plato to Pollis the Spartan, who had just arrived on an embassy, with orders to sell him into slavery

Plato fell in love with a young man named Aster... and [with] Dion... he fell in love with Alexis and Phaedrus... He also had a passion for Archeanassa... And also to Agathon... An apple am I, tossed by one who loves you. Only consent, Xanthippe! For you and I are ripening on the vine.

there are three kinds of goods... There are three kinds of friendship... There are five forms of government... There are three kinds of justice... There are three kinds of knowledge... There are five kinds of medicine... There are two kinds of law... There are five kinds of speech... There are four kinds of nobility... There are three kinds of beauty... The soul is divided into three parts... There are four kinds of perfect virtue... Rule has five divisions... There are six kinds of rhetoric... Effective speaking has four aspects... There are four ways of conferring benefits... There are four ways in which things are accomplished and completed... There are four kinds of ability... There are three kinds of benevolence... Happiness has five aspects... Of the arts there are three kinds... Good is divided into four... There are three kinds of good civic order.... There are three kinds of lawlessness... There are three kinds of contraries... There are three kinds of advice... Voice is of two kinds... There are three kinds of music. One employs only the mouth, like singing. The second employs both the mouth and the hands, as when the harp player sings to his own accompaniment. The third employs only the hands, as in harp playing. Thus music may employ either the mouth alone, or both the mouth and the hands, or only the hands....

He called the school (scholēn) of Euclides “bile” (cholēn), Plato’s discourse (diatribēn) a “waste of time” (katatribēn)... to get through life one needed either reason (logon) or a noose (brochon).

He praised those who planned to marry and did not, those who proposed to sail and did not, those who were intending to pursue a political career and did not, those who planned to rear children and did not, and those who were preparing to consort with potentates and did not

when captured and put up for sale Diogenes was asked what he was good at. He replied, “Ruling over men"... To Xeniades, the man who purchased him, he said, “Be sure to do as I tell you"...

Diogenes, who had filled the bosom of his robe with beans

Seeing women who had been hanged from an olive tree, he said, “Would that all trees bore such fruit"

Asked where he came from, he replied, “I’m a citizen of the world" [an absurd thing to say at the time]

Asked what was the most beautiful thing in the world, he said, “Freedom of speech"

Many other sayings are attributed to him, which it would take too long to recount.

Still, he was admired by the Athenians. At any rate, when a young fellow had broken Diogenes’ tub they gave the boy a flogging and presented Diogenes with a new tub... others maintain that he died by holding his breath... Over his grave they stood a column, on which they placed the statue of a dog carved in marble from Paros. In the course of time his fellow citizens also honored him with bronze statues...

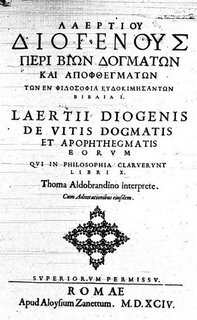

Diogenes Laertius seems to be an author whose work everyone in Renaissance Rome felt the need to own, but not to read. Among seven manuscripts... six are so perfectly preserved that they might have been written yesterday rather than half a millennium ago—virtually no one has touched them for five hundred years. It is downright depressing to think how few readers have ever seen the gorgeously illuminated capital P in MS Vaticanus Latinus 1891, with its pale pink dragonfly perched on a tendril of white filigree